Russian avant-garde

_by_Wassily_Kandinsky.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

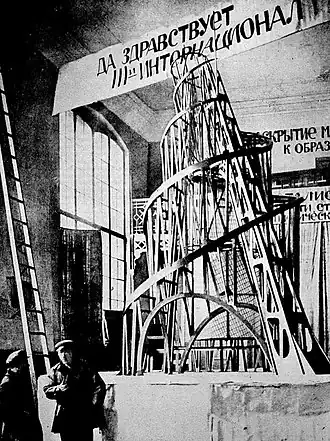

The Russian avant-garde was a large, influential wave of avant-garde modern art that flourished in the Russian Empire and the Soviet Union, approximately from 1890 to 1930—although some have placed its beginning as early as 1850 and its end as late as 1960. The term covers many separate, but inextricably related, art movements that flourished at the time; including Suprematism, Constructivism, Russian Futurism, Cubo-Futurism, Zaum, Imaginism, and Neo-primitivism.[2][3][4][5] In Ukraine, many of the artists who were born, grew up or were active in what is now Belarus and Ukraine (including Kazimir Malevich, Aleksandra Ekster, Vladimir Tatlin, David Burliuk, Alexander Archipenko), are also classified in the Ukrainian avant-garde.[6]

The Russian avant-garde reached its creative and popular height in the period between the Russian Revolution of 1917 and 1932, at which point the ideas of the avant-garde clashed with the newly emerged state-sponsored direction of Socialist Realism.[7]

Influence

The influence of the Russian avant-garde on recent developments in Western art is now undisputed. Without Kazimir Malevich's Black Square on White Background (1915), his later Suprematist composition White on White, Rodchenko's series of Black Pictures (1917/18), and his primary-colored triptych (1921), the evolution of non-representational art by artists such as Yves Klein, Barnett Newman, and Ad Reinhardt would be inconceivable. the same applies, for example, to works of American minimal art by Donald Judd and Carl Andre, which can be traced back to the materiality and functionality of early sculptures by Tatlin and Rodchenko.[8]

The founding of the National Academy of Arts in 1923, promoted by Lunacharsky, and the associated journals were primarily intended to promote exchange with Western countries. This was reflected above all in the establishment of the Soviet pavilion at the Paris Exhibition of Applied Arts in 1925 and in a major exhibition of contemporary French art in Moscow in 1928. The politicized Western art influenced by the Russian avant-garde also had an impact on Russia, as demonstrated by the exhibition of revolutionary art from the West in Moscow in 1926.[9]

Important collections

Exhibition in Chemnitz 2016/17

Under the theme “Revolutionary! Russian Avant-Garde from the Vladimir Tsarenkov Collection,” the Chemnitz Art Collections displayed 400 loans from 110 Russian avant-garde artists from the years 1907 to around 1930 on the occasion of the 100th anniversary of the Russian October Revolution.[10]

Artists and designers

Notable figures from this era include:

- Alexander Archipenko

- Vladimir Baranoff-Rossine

- Alexander Bogomazov

- David Burliuk

- Vladimir Burliuk

- Marc Chagall

- Ilya Chashnik

- Aleksandra Ekster

- Robert Falk

- Moisey Feigin

- Pavel Filonov

- Artur Fonvizin

- Naum Gabo

- Nina Genke-Meller

- Natalia Goncharova

- Elena Guro

- Vasily Kandinsky

- Lazar Khidekel

- Ivan Kliun

- Gustav Klutsis

- Anna Kogan

- Pyotr Konchalovsky

- Eugène Konopatzky

- Sergei Arksentevich Kolyada

- Alexander Kuprin

- Mikhail Larionov

- Aristarkh Lentulov

- El Lissitzky

- Kazimir Malevich

- Paul Mansouroff

- Ilya Mashkov

- Mikhail Matyushin

- Vadim Meller

- Adolf Milman

- Solomon Nikritin

- Alexander Osmerkin

- Max Penson

- Liubov Popova

- Ivan Puni

- Kliment Red'ko

- Alexei Remizov

- Alexander Rodchenko

- Olga Rozanova

- Léopold Survage

- Varvara Stepanova

- Georgii and Vladimir Stenberg

- Vladimir Tatlin

- Nadezhda Udaltsova

- Vasiliy Yermilov

- Ilya Zdanevich

- Alexandr Zhdanov

Journals

Filmmakers

- Grigori Aleksandrov

- Boris Barnet

- Alexander Dovzhenko

- Sergei Eisenstein

- Lev Kuleshov

- Yakov Protazanov

- Vsevolod Pudovkin

- Dziga Vertov

Writers

- Isaac Babel

- Andrei Bely

- Vladimir Burliuk

- David Burliuk

- Konstantin Fofanov

- Elena Guro

- Velimir Khlebnikov

- Daniil Kharms

- Aleksei Kruchenykh

- Mirra Lokhvitskaya

- Vladimir Mayakovsky

- Igor Severyanin

- Viktor Shklovsky

- Sergei Tretyakov

- Marina Tsvetaeva

- Sergei Yesenin

- Ilya Zdanevich

Theatre directors

Architects

- Yakov Chernikhov

- Moisei Ginzburg

- Ilya Golosov

- Ivan Leonidov

- Konstantin Melnikov

- Vladimir Shukhov

- Alexander Vesnin

Preserving Russian avant-garde architecture has become a real concern for historians, politicians and architects. In 2007, MoMA in New York City, devoted an exhibition to Soviet avant-garde architecture in the postrevolutionary period, featuring photographs by Richard Pare.[11]

Composers

- Samuil Feinberg

- Arthur Lourié

- Mikhail Matyushin

- Nikolai Medtner

- Alexander Mossolov

- Nikolai Myaskovsky

- Nikolai Obukhov

- Gavriil Popov

- Sergei Prokofiev

- Nikolai Roslavets

- Leonid Sabaneyev

- Alexander Scriabin

- Vissarion Shebalin

- Dmitri Shostakovich

Many Russian composers that were interested in avant-garde music became members of the Association for Contemporary Music which was headed by Roslavets.

See also

- Agitprop

- Avant-garde

- Constructivist art

- Constructivist architecture

- Cubo-Futurism

- Ego-Futurism

- Jack of Diamonds

- Imaginism

- Oberiu

- Proletkult

- Rayonism

- Russian Symbolism

- Russian Futurism

- Suprematism

- Soviet art

- Soviet montage theory

- Universal Flowering

- UNOVIS

- Vkhutemas

- Zaum

References

- ^ Wassily Kandinsky, Untitled (study for Composition VII, Première abstraction), watercolor, 1913, MNAM, Centre Pompidou

- ^ Hatherley, Owen (2011-11-04). "The constructivists and the Russian revolution in art and achitecture". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2019-12-13.

- ^ "Cubo-Futurism | art movement". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2019-12-13.

- ^ Douglas, Charlotte (1975). "The New Russian Art and Italian Futurism". Art Journal. 34 (3): 229–239. doi:10.2307/775994. ISSN 0004-3249. JSTOR 775994.

- ^ "A Revolutionary Impulse: The Rise of the Russian Avant-Garde". The Museum of Modern Art. Retrieved 2019-12-13.

- ^ "Ukrainian Avant Garde". Ukrainian Art Library. 26 January 2017.

- ^ Groys, Boris (2019-12-31), "3. The Birth of Socialist Realism from the Spirit of the Russian Avant-Garde", The Russian Avant-Garde and Radical Modernism, Academic Studies Press, pp. 250–276, doi:10.1515/9781618111425-010, ISBN 978-1-61811-142-5, S2CID 240605358

- ^ Vorwort. In: Susanne Anna: Russische Avantgarde. 1995, S. 5.

- ^ Centre Georges Pompidou: Moscou – Paris 1900–1930. Katalog, Paris 1979, S. 10–23.

- ^ Revolutionär! Russische Avantgarde aus der Sammlung Vladimir Tsarenkov. Ausstellung in den Kunstsammlungen Chemnitz, 11. Dezember 2016 bis zum 19. März 2017.

- ^ "Lost Vanguard: Soviet Modernist Architecture, 1922–32". MoMA. 2007. Retrieved 1 August 2019.

Further reading

- Friedman, Julia. Beyond Symbolism and Surrealism: Alexei Remizov's Synthetic Art, Northwestern University Press, 2010. ISBN 0-8101-2617-6 (Trade Cloth)

- Nakov, Andrei. Avant Garde Russe. England: Art Data. 1986.

- Kovalenko, G.F. (ed.) The Russian Avant-Garde of 1910–1920 and Issues of Expressionism. Moscow: Nauka, 2003.

- Rowell, M. and Zander Rudenstine A. Art of the Avant-Garde in Russia: Selections from the George Costakis Collection. New York: The Soloman R. Guggenheim Museum, 1981.

- Shishanov V.A. Vitebsk Museum of Modern Art: a history of creation and a collection. 1918–1941. – Minsk: Medisont, 2007. – 144 p.[1]

- “Encyclopedia of Russian Avangard. Fine Art. Architecture Vol.1 A-K, Vol.2 L-Z Biography”; Rakitin V.I., Sarab’yanov A.D., Moscow, 2013

- Surviving Suprematism: Lazar Khidekel. Judah L. Magnes Museum, Berkeley CA, 2004

- Lazar Khidekel and Suprematism. Prestel, 2014 (Regina Khidekel, with contributions by Constantin Boym, Magdalena Dabrowski, Charlotte Douglas, Tatyana Goryacheva, Irina Karasik, Boris Kirikov and Margarita Shtiglits, and Alla Rosenfeld)

- Tedman, Gary. Soviet Avant Garde Aesthetics, chapter from Aesthetics & Alienation. pp 203–229. 2012. Zero Books. ISBN 978-1-78099-301-0

External links

- Why did Soviet Photographic Avant-garde decline?

- Website about russian avant-garde.

- The Russian Avant-garde Foundation

- Thessaloniki State Museum of Contemporary Art – Costakis Collection

- Yiddish Book Collection of the Russian Avant-Garde at the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library at Yale University

- International campaign to save the Shukhov Tower in Moscow

- Masters of Russian Avant-garde

- Masters of Russian Avant-garde from the collection of the M.T. Abraham Foundation

- Abstraction and Estrangement across the Arts in the Russian Avant-garde: Chapter 2 in The Poetics of the Avant-garde in Literature, Arts, and Philosophy, edited by Slav Gratchev, 2020, Rowman & Littlefield.