Robert Steele & Company

| Company type | Private |

|---|---|

| Industry | Shipbuilding |

| Founded | 1815 |

| Defunct | 1883 |

| Fate | Sold to Scott & Co. in 1883 |

| Headquarters | Greenock, Scotland |

Key people | Robert Steele I, Robert Steele II |

| Parent | Steele & Carswell (1796-1815) |

_-_Robert_Steele_(1745%E2%80%931830)_-_L1977.815_-_McLean_Museum_and_Art_Gallery.jpg)

Robert Steele & Company was a shipbuilding firm based in Greenock, Scotland. The business was formed in 1815 by Robert Steele (1745-1830) and two sons. It followed the dissolution of an earlier shipbuilding partnership between Robert Steele and John Carswell, known as "Steele and Carswell."[1]

The early years

Robert Steele (1745-1830) was born to James Steele and his wife Anne nee Laurie in 1745.[2] James had a small shipyard at Saltcoats that specialised in coasters and fishing vessels and when he was old enough Robert began an apprenticeship under his father. After the death of James, Robert continued in the Saltcoats yard for another decade before deciding to go into partnership with John Carswell who had a shipyard at Greenock.

Steele and Carswell commenced operations in at their yard in the Bay of Quick to the west of Greenock in 1796. Their first vessel was the Clyde (145 tons) launched in April of the following year. The partnership lasted 20 years during which time the yard produced 35 vessels.[3] One of these was the Bengal the first East Indiaman built at Greenock. The partnership was dissolved in 1815 and a new company formed using the same yard. The new firm was called Robert Steele and Company and was a partnership between Robert and his two sons, James and Robert II. The first vessel built by the new company was the three-masted barque Rebecca.[1]

Steamships

The firm began to build steamships in 1821.[4] A new yard was established at Rue End and the Shaw’s Water Foundry and Engineering Company was purchased to make the engines and boilers for their steamers.[5] So quickly did the firm become involved in this new form of shipbuilding that in 1826 they launched the United Kingdom the largest paddle steamship in the world to that date. Soon after Robert Steele retired from the business and he died in 1830. During his time at Greenock he was involved in the construction of more than fifty vessels. Six of them were steamships, one of them the worlds largest.[6] Robert Steele the younger now took over as principal in the business; his brother, James, having died some years earlier.

By the 1840s the firm was well known as a producer of high-quality wooden-hulled paddle steamers. These were used as packets on coastal runs between ports like Glasgow and Liverpool or on short ocean crossings between Britain and mainland Europe, or Britain and Ireland. One of these was the Unicorn (650 tons) and was bought by Samuel Cunard and made the first Atlantic crossing for his firm.[7] Steeles also built the hull of the SS Columbia in 1840 and it was one of four steamships used by Cunard to fulfil the Royal Mail contracts awarded the enterprising Canadian.[8] Steele’s went on to work on all but four of the first thirteen Cunard steamers.

Steele’s prominence in the first generation of steamship construction was short-lived. Wooden-hulled paddle steamers were soon superseded by iron-hulled vessels that were faster, stronger and cheaper to maintain. These in turn were made redundant by vessels with screw propellors rather than paddles.[9] The introduction of iron-hulled vessels marked the end of Steele’s association with Cunard.

To meet the changing times Robert Steele II in 1854 opened a bigger yard at Cartsdyke West and began to build screw-steamers with iron hulls.[10] The first of these, launched later in 1854, was the S.S. Beaver. This was followed two years later with a contract to build the SS Canadian (2,000 tons) for the Allan Line.[11] The firm went on to build many more screw steamers for the line and these were used as packets between the U.K. and Canada. Orders for the Allan Line and other owners saw Steeles again in the mainstream of British shipbuilding.

Technological change continued with steel replacing iron in hull construction. Shipbuilding generally became more complex with innovations such as the compound engine and bilge keels to reduce rolling. The skill of the marine engineer gradually became more important than that of the shipbuilder. The Sardinian launched in 1874 was the last big steamer built by the firm as it found itself faced by a new wave of technological change in the industry.

Although best known at this time as a builder of large steamships, the firm had continued throughout to built sailing ships, barges and yachts. Between 1864 and 1869 the firm built 45 sailing vessels but no steamships.[12] What encouraged this return to sail was the expansion of the far-eastern and Australian routes where wind powered ships could still compete with steam vessels. Among the firms achievements during this period was the construction of a number of tea-clippers.

The tea clippers

The company built twenty China tea clippers, the first of which was the Kate Carne in 1855.[13][14] Many of these went on to win the China Tea Races.[1]

The following are some of the Tea Clippers built by Robert Steele & Company:

| Vessel Name | Material | Owners / Agents | Date Built | Period Owned | Net Tonnage | Length Overall (feet) | Breadth (feet) | Depth(feet) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ariel | Composite | Shaw, Lowther & Maxton | 1865 | 1865-1872 | 853 | 197.4 | 33.9 | 21 |

| Chinaman | Composite | 1865 | 668 | |||||

| Ellen Rodger | Wooden | Alexander Rodger & Co | 1858 | 1858-1866 | 585 | 155,8 | 29.4 | 19.5 |

| Falcon | Wooden | Phillips, Shaw & Lowther | 1859 | 1859-1900 | 794 | 191.4 | 32.2 | 20 |

| Guinevere | 1862 | 647 | ||||||

| Kaisow | Composite | Alexander Rodger | 1868 | 1868-1891 | 820 | 193.2 | 32 | 20.3 |

| Kate Carnie | Wooden | Alexander Rodger & C. Carnie | 1855 | 1855-1889 | 576 | 148.4 | 26 | 19 |

| King Arthur | Iron | 1862 | 699 | |||||

| Lahloo | Composite | Alexander Rodger & Co | 1867 | 1867- 1872 | 799 | 191.6 | 32.9 | 19.9 |

| Min | Wooden | Alexander Rodger & Co | 1861 | 1861-1891 | 629 | 174.5 | 29.8 | 19.3 |

| Serica | Composite | James Findlay | 1863 | 1863-1872 | 708 | 185.9 | 31.1 | 19.6 |

| Sir Lancelot | Composite | John McCunn | 1865 | 1865-1895 | 886 | 197.6 | 33.7 | 21 |

| Taeping | Composite | Alexander Rodger | 1863 | 1863-1871 | 767 | 183 | 31.1 | 19.9 |

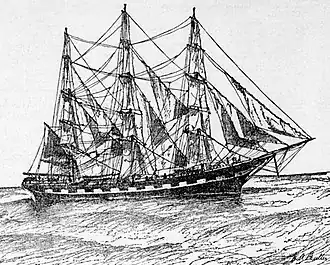

| Titania | Composite | Shaw, Lowther, Maxton & Co | 1866 | 1866-1910 | 879 | 200 | 36 | 21 |

| Wylo | Composite | Killick Martin & Company | 1869 | 1869-1886 | 829 | 192.9 | 32.1 | 20.2 |

| Young Lochinvar | Wooden | John McDiarmid | 1863 | 1863-1866 | 724 | 183.0 | 31.0 | 19.0 |

From 1854 the company started building iron ships, such as Irish ferry, ss Mangerton, an 1855 Robert Steele steamship,[15] which struck wooden barque Josephine Willis in 1856

Achievements

The company was one of the shipbuilders credited with the development of the four-masted barque along with Alexander Stephen and Sons.[16]

Robert Steele built Knock Castle as a private home on the coast near Largs in 1851-2.[17] It still stands today (July 2025).

Robert Steele was sometimes called on to give expert testimony on shipping matters.[18]

Other shipbuilders who began with Steele’s before branching out on their own include Charles Connell.

Gallery

-

America (1859)

America (1859) -

Ariel & Taeping (1866)

Ariel & Taeping (1866) -

.jpg) Eliza Stewart (1847)

Eliza Stewart (1847) -

Ellen Rodger (1858)

Ellen Rodger (1858) -

.jpg) Helen (1865)

Helen (1865) -

SS La Plata (1852)

SS La Plata (1852) -

Ravenscrag (1898)

Ravenscrag (1898) -

Sardinian (c1890)

Sardinian (c1890) -

.jpg) Titania, by Jack Spurling

Titania, by Jack Spurling -

.jpg) HMS Waterwitch (1892)

HMS Waterwitch (1892)

References

- ^ a b c Howard, Mark. "Robert Steele and Company: Shipbuilders of Greenock" (PDF). The Northern Mariner. II (3). Canadian Nautical Research Society: 17–29. Retrieved 18 September 2016.

- ^ Howard, p.18.

- ^ David, MacGregor (1980). Merchant Sailing Ships, 1775-1815; Their Design and Construction (First ed.). Watford: Argus Books. p. 125. ISBN 0852426631.

- ^ "Greenock Telegraph and Clyde Shipping Gazette (GT)". 14 February 1956.

- ^ G.T, 21 February 1956

- ^ David S. McMillan, “The new men in action: Scottish mercantile and shipping operations in the North American Colonies, 1760-1825,” p.45, in, David S. McMillan (ed.), Canadian Business History; selected studies, 1497-1971, Toronto, 1972.

- ^ G.T., 28 February 1956.

- ^ Shields, John (1949). Clyde-built: A History of Shipbuilding on the River Clyde. Glasgow. p. 121.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Howard, p.23.

- ^ G.T., 29 March 1956.

- ^ MacGregor, David R. (1961). The China Bird:The History of Captain Killick and one Hundred Years of Sail and Steam (First ed.). London: Chatto & Windus. p. 62.

- ^ G.T., 5 April 1956.

- ^ I.E.O. (1963). Steele-built: The Story of a Greenock Shipyard and its ships (First ed.). Greenock. p. 20.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ MacGregor, David R. (1972). The Tea Clippers: An Account of the China Tea Trade and some of the Some of the British Sailing Ships Engaged in it from 1849 to 1869. Whitstable: Conway Maritime Press. p. 76. ISBN 0851770592.

- ^ "Shipyards: Robert Steele & Co". www.bruzelius.info. Retrieved 26 April 2019.

- ^ Nick Robins (21 January 2014). Scotland and the Sea: The Scottish Dimension in Maritime History. Seaforth Publishing. pp. 93–. ISBN 978-1-4738-3441-5.

- ^ "Knock Castle". trove.scot. Historic Environment Scotland. Retrieved 28 July 2025.

- ^ Steele Robert (1834). Report to the Chamber of Commerce of Greenock on the admeasurement of shipping for tonnage (First ed.). Greenock. Retrieved 30 July 2025.