Renaissance in Albania

The Albanian Renaissance, also known as the Arbëresh Renaissance, was an important cultural and political period in the history of Albania in the 15th–17th centuries. It was a part of the Southern renaissance and came from the Italian Renaissance.

During the 15th century AD, the ideas of the Renaissance would reach Albania through coastal trade cities such as Scutari, Durrës, Ulcinj, Kotor, and Tivar, with these cities evolving into Adriatic trading centers. The ideas of the Renaissance would lead to Albanian development in art, literature, education, science, and diplomacy.

With the end of the Albanian–Ottoman Wars (1432–1479), many humanist scholars would migrate to foreign countries such as Italy to escape Ottoman rule. This led to most early Albanian documents being lost or forgotten and most texts written by Albanians in this time being in Latin. Few scholars would remain in Albania, such as Gjon Buzuku, Pjetër Budi, Pjetër Bogdani, Frang Bardhi, and Onufri. Scholars that lived outside of Albania, such as Marin Barleti, Dhimitër Frëngu, or Marin Beçikemi, dedicated most of their work to Skanderbeg and his "heroics", picturing him as a national hero.

Background

Pre-Renaissance Albania

Before the Renaissance, Albania had little development in science and in preserving its own language. Most schools focused on religious studies instead of scientific ones. In terms of literature, Albanians did not use their own language. Despite having their own, in books, documents, and daily interactions they would use Greek or Latin. This usage of foreign languages was also documented by the bishop of Tivar, Guillem Adam, who in a letter to the French king in 1332 would state:[1][2]

Although the Albanians have another language totally different from Latin, they still use Latin letters in all their books.

The first known document originally written in Albanian that was later translated to Latin is the "Baptismal formula" by the bishop of Durrës, Pal Engjëlli, in 1462, which today is located in the library of Florence. The second known document is a part of the Easter Gospel Pericope though to have been written around the late 15th century – early 16th.[3]

Period

Through coastal cities on the Adriatic coast such as Scutari, Durrës, Ulcinj, Kotor, and Tivar, the ideas of the renaissance would reach Albania via books and documents near the end of the 15th century. Due to Ottoman rule, many scholars migrated to Italy where they would create works on Skanderbeg and Albanian nationalism, while the ones that remained in Albania would focus on preserving Albanian traditions, language, and culture through religious works. The period was also characterized by the opening of schools and universities.[4][5]

Literature

From the Albanian authors that lived outside of Albania, the most notable would be Demetrio Franco (Dhimitër Frëngu), Marin Barleti, Marin Beçikemi, and Anonimi Tivaras. One of the earliest books written by the Albanian diaspora was Historia Skanderbegiae (History of Skanderbeg), also known as History of the Kastrioti named Skanderbeg, published in 1480 in Venice by Anonimi Tivaras.[6][7] Other books published on Skanderbeg during this time were Siege of Shkodra and Historia de vita et gestis Scanderbegi Epirotarum principis (1504) by Marin Barleti[8][9] and Gli illustri e gloriosi gesti e vittoriose imprese fatte contro i Turchi dal Signor Don Georgio Castriotto detto Scanderbeg, principe d' Epiro by Dhimitër Frëngu, who also wrote a biography on him.[10][11] Marin Beçikemi would be another author known for his works on Albania after the Ottoman invasion, as well as the translation of ancient Roman texts.[12][13]

From authors that remained in Albania, the most notable were Gjon Buzuku, Pjetër Bogdani, Pjetër Budi, and Frang Bardhi. Gjon Buzuku wrote the first-ever Albanian book, originally written in the Gheg dialect, Meshari, in 1555. Meshari is the translation of the main parts of the Catholic Liturgy into Albanian. It contains the liturgies of the main religious holidays of the year, comments from the book of prayers, excerpts from the Bible, and excerpts from the ritual and catechism.[14] Pjetër Bogdani would also publish a book focused on Catholicism, the Çeta of Prophets (Cuneus Prophetarum).[15] Pjetër Budi is another writer known for his works and translations on religion which would be published in Rome, and in 1618 he wrote 100 pages of prose as well as 3,200 verses of poetry, which would be published in the Christian Doctrine.[16] Frang Bardhi was another notable Albanian writer and bishop, known for trying to preserve the Albanian language. In 1635, he published the first Albanian dictionary, Dictionarium latino-epiroticum (Latin-Albanian dictionary), and in 1636 he wrote a biography of Skanderbeg, titled The Apology of Scanderbeg.[17][18]

Art

In Albania, the most notable painters were Onufri and his son Nikolla. Art during the Renaissance in Albania focused mostly on Christian religious figures, despite the ideas of the Renaissance, which focused more on science. Many painters would paint in churches or monasteries, with most of their works focusing on prophets or Jesus, such as Nikolla who painted in the Church of St. Vllaherna in Berat.[4] The artistic works of this period, especially from Onufri, would leave an influence on Albanian art up until the 19th century. Onufri introduced a new style of painting with him using natural color dies as well as introducing the color pink into paintings. He would paint religious and historical figures as well as nature. Onufri also established the first Albanian art school in Berat, which would later be passed down to Nikolla.[19][20]

Education

Previously the main form of education in Albania came from Monasteries or churches where the main subject was theology. This education system aimed to make students grow up and be monks or priests. This form of education became widespread during the 13th century with the arrival of Franciscan and Dominican missionaries, who opened several churches in larger cities. The Renaissance would bring the appeal of critical thinking to education leading to the teachings of the seven liberal arts (both trivium and quadrivium). The University of Durrës would "flourish" during this time; however, it would be abandoned by its staff in the Ottoman invasion. They opened a new university in Tivar. Many Albanians living outside of the country would also achieve education in multi-cultural colleges such as the College of Loreto and the Illyrian College of Fermo.[21] Schools were also established; however, the earliest known schools come in the later Renaissance period. The earliest known Albanian school is the school of Veles in Mirdita, opened in 1632, but there was also a school opened in Kurbinë the same year which could have been older. Other schools included the school of Himarë, the school of Pllana in Karadak, of Blinisht, of Shkodër, Orosh, Janjevë, Durrës, Gjakova, and Peja.[22]

Architecture

Architecture was another field which gained popularity in Albanian people with the coming of the Renaissance. It had influence from Bizantine style architecture as well as roman and gothic style. Most famous Albanian architects at this time worked on projects outside of Albania, mainly in the Ottoman Empire and Italy. Some of the most famous architects that worked in the Ottoman lands were Architect Kasemi and Sedefkar Mehmed Agha, while from the architects that worked in Italy the most famous was Andrea Alessi, who also worked in Dalmatia. From architectural works in Albanian lands, only a handful of monuments built around the 14th-15th centuries, mainly churches, remain such as the Churches of Shirgji, St. Stephan, Vaut in Deja, Berat and Myzeqe. After the Ottoman invasion most churches would be destroyed and replaced with mosques.[4]

Architect Kasem and Mehmed Agha were famous for working on mosques in Istanbul, with their style having large ottoman influence. Mehmed Agha is famous for constructing the Blue Mosque also known as the Sultan Ahmed Mosque.[23] Architect Kasem would be another famous architect who is known for works such as the Baghdad Kiosk, Revan Kiosk and Tiled Kiosk in the Topkapı Palace, as well as the projecting of the Spice Bazaar in Istanbul which is the second largest covered shopping mall. Kasem would also create many structures in Albania such as inns, bridges, roads and baths.[24]

Some also theorise that the Ottoman architect Mimar Sinan, who was one of the architects of the Topkapı Palace who also projected many other bridges and mosques in ottoman lands, to have been of Albanian origin.[25][26]

Andrea Alessi would be another architect famous for his unique style. His most notable work was the Baptistry of Trogir, located in Trogir, Croatia. Alessi also projected many merchant statues and cathedral expansions. Most of his work would be carried out in Dalmatia.[27]

History

History would be another field which would see large developments during the Albanian renaissance with the ideas of preserving Albanian culture and language. During this time the most notable historians would be Frang Bardhi, Marin Barleti (who were also writers) as well as Gjon Muzaka. Frang Bardhi is famous for his work The Apology of Skanderbeg, a book which depicts the entire life of the Albanian general.[17][18] Marin Barleti's historical works are the "Siege of Shkodra" and the "The history of the life and deeds of Scanderbeg, the Prince of Epirus". The Siege of Shkodra is a book on the on the Siege of Shkodra (1478-1479) which he wrote after being an eyewitness of the battle. The book depicts the "bravery" of the Albanian people in war and describes events from the siege. His second work is one of the earliest and most used books about Skanderbeg, with it being used as a primary source on most works on Skanderbeg.[8][10] Despite this, some events from Barleti's books are not real or different from real events and are criticized, such as the correspondence between Vladislav II of Wallachia and Skanderbeg which he wrongly assigning it to the year 1443 instead of 1444 aswell as the correspondence between Skanderbeg and Sultan Mehmed II to match his interpretations of events.[28]

Gjon Muzaka is known for writing the Muzaka chronicles in 1510, a series of documents which describe the history of Muzaka Principality as well as the other Albanian noble houses during the middle ages,[29] however Gjon Muzaka is criticized for his chronicles having "bias" with him depicting his house as a higher one oppose to the others.[30]

Important figures

Anonimi Tivaras

Anonimi Tivaras (Anonymous Tivaras), also known as Antivarino, is an unknown Albanian writer who wrote Historia Skanderbegiae (History of Skanderbeg), the first biography on Skanderbeg, published in 1480. He would first be mentioned when his book was used as a source by Italian historian Giammaria Biemmi, who would state that Anonimi Tivaras's brother was an officer of Skanderbeg. The information mentioned in his work matches that of Marin Barleti's. His identity remains unknown, and copies of his original book are lost due to the author having "poor Latin".[31][6][7]

Pal Engjëlli

Pal Engjëlli (1416–1470) was an Albanian prelate of the Roman Catholic Church and archbishop of Durrës.[32] He wrote the first Albanian document and also served and important role in the advancement of diplomacy in Albania during the early renaissance. He was born into the feudal Engjëlli family and would serve as a counselor of Skanderbeg.[3] He would do several diplomatic missions across Europe during this time and would also convince Lekë Dukagjini to betray the Ottomans.[33]

Marin Barleti

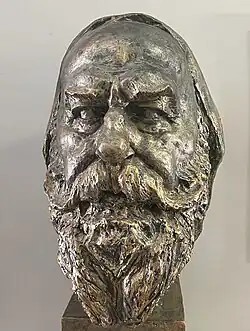

.jpg)

Marin Barleti (1450-1454–1512) was an Albanian humanist, historian, writer, and priest from Shkodër. He is considered as the first Albanian historian due to him being an eyewitness to the Siege of Shkodra about which he wrote a book with the same title.[34] In 1504 he published Historia de vita et gestis Scanderbegi Epirotarum principis (The history of the life and deeds of Skanderbeg, the Prince of Epirus).[35] His third and lesser-known work is titled A Brief History of Lives of Popes and Emperors. After leaving Albania he was given Venetian citizenship and a stall at a meat market in Rialto before becoming a priest after his theological studies at Venice and Padova and would soon be appointed to serve at St. Stephens Church in Piovene.[36]

Dhimitër Frëngu

Dhimitër Frëngu, also known as Demetrio Franco (1443–1525), was an Albanian historian and writer born in Drivast. He was a cousin of Pal Engjëlli and served under Skanderbeg. After the Ottoman invasion, he settled in Italy, where he published the biography about Skanderbeg in 1480 as well as another book titled Gli illustri e gloriosi gesti e vittoriose imprese fatte contro i Turchi dal Signor Don Georgio Castriotto detto Scanderbeg, principe d' Epiro.[10][15]

Marin Beçikemi

Marin Beçikemi (1468–1526), also known in Italian as Marino Becichemo, was an orator, teacher, and writer from Shkodra. He would spend most of his life in Brescia, where he studied Latin and ancient Greek. Beçikemi worked as a professor in both the universities of Brescia and Padua. He is known for his works on Albanian history and the study of ancient texts and comments on ancient philosophers and writers, such as his book Castigationes et observationes in Virgilium, Ovidium, Ciceronem, Servium et Priscianum. In 1495, he was dedicated to the Ragušan Senate, where he befriended humanist Ivan Gučetić. In 1500, Marin Beçikemi gained Venetian citizenship.[13]

Gjon Buzuku

Gjon Buzuku (1499–1577) was an Albanian priest and author known for his attempts at conserving the Albanian language. His books focused on Catholicism, and he is believed by scholars to have worked for a short amount of time as a priest in the church of Venice. Gjon Buzuku wrote the first Albanian book, in the Gheg dialect, titled Meshari, in 1555.[37] Little is known about his personal life or family, as both the front and back pages of his book which could have held information about himself are lost. The only known family member of his is his father, Bdek (Benedict) Buzuku.[14]

Pjetër Budi

Pjetër Budi (1566–1622) was an Albanian bishop, writer, and poet born in Gur i Bardhë. He would become a famous poet, writing 3,300 lines of poetry.[38] Budi completed his studies at the Illyrian College of Loreto for priesthood. In 1599 he was appointed Vicar general of the Catholic church in Serbia, a position which he would hold for seventeen years, before leaving to become the bishop of the Diocese of Sapë.[39] He is known for publishing the "Christian Doctrine" (Doktrina e Kërshtenë), one of the earliest Albanian books. It was published in Rome in 1618. Pjetër Budi died in December 1622 while crossing the Drin river.[40]

Pjetër Bogdani

Pjetër Bogdani (1627–1689) was a scholar, priest, writer, poet, and resistance fighter from modern-day Gjonaj in Kosovo.[41] He is known for writing the book Çeta of the Prophets, also known as the Band of Prophets, in 1685, the first prose written in Gheg Albanian. In 1689 he led an uprising against the Ottomans with help from the Holy League. The uprising spread across Kosovo, leading to the capture of Prizren and Pristina. With his works, Bogdani strove to create an understanding of existence, God, science, theology, philosophy, geography, physics, astronomy, and history. He died in 1689 in Pristina.[42][43]

Frang Bardhi

Frang Bardhi (1606–1643) was a Catholic bishop and scholar from Nënshat. He came from a family of Albanians linked to the Catholic church and military generals in Venice. He completed his theology studies in Italy before being appointed as the Bishop of Sapë on 17 December 1635. Bardhi is known for writing the Latin-Albanian Dictionary (Dictionarium latino-epiroticum) the same year, which consisted of 5,640 entries with its appendix containing 113 proverbs, phrases, and idioms, including some from Albanian folklore. He also published the Apology of Scanderbeg in 1638, which was a biography and polemic against the Slavic church priest Ivan Tomko Mrnavić, who claimed that Skanderbeg was Albanian. Bardhi also gave political reports on Albanian customs to Italy.[44][17][18]

Andrea Bogdani

Andrea Bogdani (1600–1683) was a scholar and prelate of the Roman Catholic church. He was the uncle of Pjetër Bogdani and was born in Gjonjan. Andrea received his education by Jesuits in the Illyrian College of Loreto before becoming a parish in Pristina. He wrote the first Albanian-Latin grammar book, which is now lost. Bogdani's other works have been criticized for forgery and revisionism from Serbian medieval history.[45]

Llukë Bogdani

Llukë Bogdani (died 1687), also known as Luca Bogdano, was a scholar of the Bogdami family and cousin of Pjetër Bogdani. He was one of the first Albanian poets, known for writing the poem Pjetër Bogdanit, argjupeshkëpit Skupsë, kushërinit tim dashunit (To my dear cousin Petro Bogdano, Archbishop of Skopje), an eight-line poem deticated to Pjetër Bogdani, which was published in the early versions of Cuneus Prophetarum (Çeta of the Prophets) in 1685, later removed for being religiously "inappropriate".[46][47]

Gjon Gazuli

Gjon Gazuli (1400–1465) also known as Gjin Gazuli or Gjon Gjin Gazuli was a scholar, astronomer, diplomat, and Dominican friar from the Republic of Ragusa of Albanian origin. Gazuli received his education in schools such as the schools of Shkodër and Dubrovnik before completing University in Padua in 1430. He began working as a diplomat for Skanderbeg and the League of Lezhë in 1432, carrying out various diplomatic missions in Hungary. He also served as a diplomat in the courts of Italian principalities, representing the interests of the Albanian resistance. He would be regarded by people in Italy and Hungary as a good scientist with a reputation of "considerable knowledge" and his works, mainly in Latin and about astronomy and mathematics, contained large amounts of information.[48][49]

Onufri

Onufri, also known as Onouphrios of Neokastro or Onouphrios Argytes, was an archpriest and artist known for his "unique" style of art, mainly working on murals inside of Orthodox churches. Onufri's works were different from other eastern European artists at the time, as he included natural dyes and the color pink in his works, which differed from even those of Italian and western European artists. He played an important role in Albanian art, opening the first art university in Albania and having an influence that lasted until the 19th century. He was active in Berat and in Venice during 1547; however, from 1555, he began prioritizing Southern Albania, painting in church murals in Berat, Kastoria, the village of Shelcan near Elbasan, the village of Valsh, and the church of St. Nicholas in Prilep.[50] His signature Protopapas, used in all of his works, demonstrated that he had a senior position in the church. Onufri's most notable works include "The Resurrection of Lazarus", "Fresco", and "Sts Peter and Paul Fresco" (murals), "Mary and Child", murals in the church of Berat, "Prophet David", and the "Unknown Painter".[51][52]

Nikolla

Nikolla was a famous painter and the son of Onufri. His birth and death date remain unknown. Nikolla's painting were very similar to his fathers, as they both painted mainly in murals. One of Nikollas most famous mural works was when he painted the murals of the St. Mary of Blachernae Church in Berat, where he painted the Roman Emperor Constantine I and his mother Helena of Constantinople finding the Holy cross in Jerusalem.[53] His other most notable work is an icon of the Apostle Saint Peter painted during the second half of the 16th century, held today in the Onufri Museum in Berat. After the death of Onufri, Nikolla became the head of the Arts school of Berat, and after his passing it would be given to Onouphrios Cypriotes.[4]

Bernardino Vitali

Bernardino Vitali was an Albanian publisher and printer active in Venice from 1494 to 1539. His workshops, also located in other cities like Rome and Rimini, published more than 200 works of Italian and Albanian humanist scholars, playing a crucial role in the development of literature in the Renaissance.[54] He was the editor and publisher of Marin Barleti, and he also published many books by Marin Beçikemi. Another one of his most notable publications was Tabulae Anatomicae by Andreas Vesalius. Vitali also worked with his brother Matteo, who was the co-owner of the Vitali workshop.[55]

References

- ^ Xhevat, Lloshi (1999). Handbuch der Südosteuropa-Linguistik. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. p. 291. ISBN 978-3-447-03939-0. Retrieved 17 May 2012.

The first attempts to write the albanian language are to found in the 12th - 13th centuries. It is understandable that the first documents may have been trade, economic, administrative and religious wrtitings compiled by low-rank clerics. A Dominican friar, Guillelmus Adae, knows as Father Brocardus, noted in a pamphlet he published in 1332 that "the Albanians have a language quite other than the Latin, but they use the Latin letters in all their books".

- ^ Demiraj, Shaban. "Albanian". In Ramat and Ramat (2006), The Indo-European Languages. Page 480

- ^ a b Janet, Byron (1976). Selection among alternates in language standardization: the case of Albanian. Mouton. p. 36. ISBN 978-90-279-7542-3. Retrieved 17 May 2012.

in Albanian is the short Catholic baptismal formula (Formula e pagezimit) of 1462.2 The formula is in Geg, and written in Roman script; it occurs within a pastoral letter, itself in Latin, of the Archbishop of Durres, Pal Engjelli

- ^ a b c d Historia e popullit shqiptar I, Mesjeta. Toena. 2002.

- ^ "Humanizmi dhe Renesanca te Shqiptarët". prezi.com.

- ^ a b "Anonimi Tivaras". wiki.shqipopedi.org. 7 October 2018.

- ^ a b Frashëri, Kristo (2002) (in Albanian), Gjergj Kastrioti Skënderbeu: jeta dhe vepra, p. 9.

- ^ a b Robert Elsie (2005). Albanian Literature: A Short History. I.B.Tauris. ISBN 978-1-84511-031-4. Retrieved 29 May 2012.

- ^ Nadin, Lucia. Albania ritrovata. Recuperi di presenze albanesi nella cultura e nell'arte del Cinquencento veneto. Tirana: Onufri, 2012, p. 48

- ^ a b c Prenushi, Mikel. "Meshtari Dhimiter Frangu (Demetrio Franco) (1443 - 1525) Luftëtar dhe historian i Skenderbeut" (in Albanian). Archived from the original on 30 October 2020. Retrieved 1 April 2011.

- ^ Shuteriqi, Dhimitër (1978). Shkrimet shqipe në vitet 1332-1850 (in Albanian). Rilindja. p. 42. Retrieved 1 April 2011.

- ^ Paul Oskar Kristeller; Ferdinand Edward Cranz; Virginia Brown (1980). Mediaeval and Renaissance Latin Translations and Commentaries. Catholic University of America Press. pp. 352–354. ISBN 978-0-8132-0547-2.

- ^ a b Clough, Cecil H. (1965). "BECICHEMO, Marino". Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani, Volume 7: Bartolucci–Bellotto (in Italian). Rome: Istituto dell'Enciclopedia Italiana. ISBN 978-88-12-00032-6.

- ^ a b Genesin, Monica; Matzinger, Joachim (2021). "4 Old Albanian". Comparison and Gradation in Indo-European. pp. 81–94. doi:10.1515/9783110641325-004. ISBN 978-3-11-064132-5.

- ^ a b Elsie, Robert (2005). Albanian literature: a short history (2005 ed.). I.B.Tauris. p. 248. ISBN 978-1-84511-031-4.

- ^ Robert, Elsie. "Pjetër BUDI". Archived from the original on 9 June 2010. Retrieved 20 September 2010.

- ^ a b c Bihiku, Koço (1980). A history of Albanian literature. Tirana: 8 Nëntori Publishing House. pp. 14, 15. OCLC 9133663.

- ^ a b c Georgius Castriotus Epirensis, vulgo Scanderbegh. Per Franciscum Blancum, De Alumnis Collegij de Propaganda Fide Episcopum Sappatensem etc. Venetiis, Typis Marci Ginammi, MDCXXXVI (1636).

- ^ Popa, Theophan (1974). "Onufri, master of fantasy and realism: a 16th-century Albanian painter of icons and frescoes virtually unknown outside his country". The UNESCO Courier. 27. UNESCO: 13–17.

- ^ Masters, Tom (2007). Eastern Europe. Lonely Planet. p. 49. ISBN 978-1-74104-476-8.

- ^ Nikollë, Loka (January 2017). "The development of education in medieval Albania". academia.edu.

- ^ "Shkollat e para shqipe gjatë mesjetës". shtepiaelibrit.com. 13 March 2015.

- ^ Kiel, Machiel (1990). Ottoman Architecture in Albania, 1385-1912. Islamic art series. Vol. 5. Research Centre for Islamic History, Art and Culture. ISBN 9290633301.

- ^ Meksi, Aleksandër (2016). "The Architecture of Mosques in Albania During the 15h to 19h Centuries [Arnavutluk'taki Cami Mimarisi]". In Muhammet Savaş Kafkasyalı (ed.). Balkanlarda Islam: Miadi Dolmayan Umut [Islam in the Balkans: Unexpired Hope]. TİKA. pp. 157–194. ISBN 978-605-9642-11-8.

- ^ Cragg, Kenneth (1991). The Arab Christian: A History in the Middle East. Westminster John Knox Press. p. 120. ISBN 0-664-22182-3.

The greatest of all Muslim architects, Sinan ... was of Greek or Albanian Christian origin

- ^ Brown, Percy (1942). Indian architecture: (The Islamic period). Taraporevala Sons. p. 94.

… the fame of the leading Ottoman architect, Sinan, having reached his ears, he is reported to have invited certain pupils of this Albanian genius to India to carry out his architectural schemes.

- ^ Zeneli, Fidan; Qerimi, Muhmet (2023-07-13). "The development of Albanian art during the Middle Age". Street Art and Urban Creativity. 9 (1): 6–9. doi:10.25765/sauc.v9i1.687 – via ap2.pt.

- ^ Setton, Kenneth (1976–1984), The Papacy and the Levant, 1204-1571, vol. four volumes, American Philosophical Society, p. 73, ISBN 978-0-87169-114-9,

... The spurious correspondence of July and August 1443, between Ladislas and Scanderbeg (made up by Barletius, who should assigned it to the year 1444) ... He also invented a correspondence between Scanderbeg and Sultan Mehmed II to fit his interpretations of the events in 1461—1463 ...

- ^ "1515 John Musachi: Brief Chronicle on the Descendants of our Musachi Dynasty". www.albanianhistory.net. Retrieved 2024-11-29.

- ^ Omari, Jeton (2014). Scanderbeg tra storia e storiografia [Skanderbeg between history and historiography] (PDF) (Thesis). University of Padua.

- ^ Istoria di Giorgio Castrioto Scanderbeg-Begh.

- ^ Newmark, Leonard; Philip Hubbard; Peter R. Prifti (1982). Standard Albanian: a reference grammar for students. Andrew Mellon Foundation. p. 3. ISBN 9780804711296. Retrieved 2010-05-28.

- ^ Deuxième Conférence des études albanologiques: à l'occasion du 5e ... Vol. 1. 1969. p. 64. Retrieved 2010-05-28.

- ^ Barleti, Marin (2012). David Hosaflook (ed.). The Siege of Shkodra: Albania's Courageous Stand Against Ottoman Conquest, 1478. Translated by David Hosaflook. Onufri Publishing House. pp. xxix, 11. ISBN 978-99956-87-77-9.

- ^ Noli, Fan Stilian (1924). Storia di Scanderbeg (Giorgio Castriotta) re d'Albania: 1412-1468 (in Italian). Rome: V. Ferri. p. 7.

- ^ Plasari, Aurel; Nadin, Lucia (2022). Barleti i hershëm sipas një dorëshkrimi të panjohur [The early Barleti - according to an unknown text]. Albanian Academy of Sciences/Onufri. ISBN 978-9928-354-88-4.

- ^ "Meshari i Gjon Buzukut".

- ^ "Dottrina Christiana – Pjeter Budi". bibliotekashkoder.com. Retrieved 2020-11-11.

- ^ Elsie 2010, p. 52–53.

- ^ Elsie, Robert (2003). Early Albania: A Reader of Historical Texts, 11th-17th Centuries. Olzheim/Eifel, Germany: Harrassowitz Verlag. pp. 170–174. ISBN 3-447-04783-6.

- ^ Elsie 2010, p. 46.

- ^ Elsie, Robert (2003). "Albanian Literature - an overview of its history and development". In Peter Jordan; et al. (eds.). Albanien: Geographie - Historische Anthropologie - Geschichte - Kultur - Postkommunistische Transformation. Vienna: Lang. pp. 243–276.

- ^ Malcolm 1998, p. 148.

- ^ Cheney, David M. "Bishop Francesco Bianchi". Catholic-Hierarchy.org. Retrieved June 16, 2018.

- ^ Marmullaku, Ramadan (1975). Albania and the Albanians. C. Hurst. p. 17. ISBN 0-903983-13-3.

- ^ Dushi, Minir (1999). "Xehetaria e Kosovës gjatë shekujve". Dardania (1): 85.

- ^ Mann, Stuart (1955). Albanian literature: an outline of prose, poetry, and drama. B. Quaritch. p. 6.

- ^ Frashëri 2002, p. 170.

- ^ Proleksis enciklopedija LZMK Gazuli (Gazulić), Gjin (Ivan, Joannes) Refresged: February 20, 2014. Accessed June 9, 2016 (in Croatian)

- ^ Nikolovski, Darko. "Carskite dveri od crkvata Sv. Nikola vo s. Zrze - Prilep ['The Royal Doors from the church of St.Nicholas in Zrze-Prilep']". Archived from the original on 5 October 2013. Retrieved 1 December 2011.

- ^ Popa, Theofan. Ikona dhe miniatura mesjetare në Shqipëri. Tirana: 8 Nëntori, 1974.

- ^ Tourta, Anastasia; Zias, Nikos; Kourkoutidou-Nikolaidou, Eugenia; Glozhen, Lorenc (2006). Icons from the Orthodox Communities of Albania: Collection of the National Museum of Medieval Art, Korce. Thessaloniki: Museum of Byzantine Culture, Thessaloniki; European Centre tor Byzantine and Post-Byzantine Monuments, Thessaloniki; National Museum of Medieval Art, Korcë. p. 20. ISBN 960-89061-0-5. Retrieved 7 August 2017.

Nothing is known of Onouphrios's life,... from the church of this saint in Berat.

- ^ Klodjana Gjata, Marsela Demaj, Ronela Çuku. "Architecture, identity and phases of construction of the Byzantine church of St. Mary Vllaherna – Berat/Albania" (PDF). dspace.epoka.edu.al.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Tammaro De Marinis (1937). Bernardino dei Vitali (Enciclopedia Italiana)

- ^ Chevallier, Jacques (2014). "La destinée des bois de la Fabrique de 1543" (PDF). Histoire des sciences médicales. XLVIII: 178.

Sources

- Elsie, Robert (15 November 2010). Historical Dictionary of Kosovo. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-8108-7483-1.

- Malcolm, Noel (1998). Kosovo: A Short History. Macmillan. ISBN 9780333666128.

- Frashëri, Kristo (2002). Gjergj Kastrioti Skënderbeu: jeta dhe vepra, 1405–1468 (in Albanian). Botimet Toena. ISBN 99927-1-627-4.