Ramparts of Vannes

| Remparts de Vannes | |

|---|---|

| Vannes, Morbihan, Brittany, France | |

Map of Vannes city center in 1785. | |

| Site information | |

| Owner | City of Vannes Private property |

| Location | |

| Coordinates | 47°39′22″N 2°45′22″W / 47.65606°N 2.75603°W |

| Site history | |

| Built | Third century castrum Gallo-Roman – mid–17th century final developments |

The Ramparts of Vannes are the fortifications erected between the 3rd and 17th centuries to protect the city of Vannes in the Morbihan department in France. Founded by the Romans at the end of the 1st century BC under the reign of Augustus, the civitas Venetorum was forced to protect itself behind a castrum at the end of the 3rd century, during a major crisis shaking the Roman Empire. This first enclosure remained the city’s only protection for over a millennium. During the time of Duke John IV, at the end of the 14th century, the city’s enclosure was rebuilt and extended southward to protect the new districts. The duke wanted to make Vannes not only a place of residence but also a stronghold he could rely on in case of conflict. The area of the city intra-muros was doubled, and the duke added his Château de l’Hermine to the new enclosure.

The Wars of the League at the end of the 14th century forced the city to equip itself with several polygonal bastions (Gréguennic, Haute-Folie, Brozilay, Notre-Dame). The Garenne spur was the last defensive structure built in Vannes around 1630. From 1670, King Louis XIV sold parts of the ramparts piece by piece to finance his wars. The most significant event was, in 1697, the donation to the city of Vannes of the ruins of the Château de l’Hermine, which were then used for the redevelopment of the port and the maintenance of municipal buildings.

The urban developments of the 19th century led to the demolition of several segments of the northern and western walls. It was not until the partial destruction in 1886 of the Prison Gate, one of the oldest entrances to the old city, that Vannes residents attached to their heritage came together to form a heritage defense association in 1911. This led to the gradual establishment of protection for the ramparts as historical monuments between 1912 and 1958. For several decades, the city has been undertaking the restoration and enhancement of the parts of the ramparts it owns. A cornerstone of Vannes’ heritage and a quintessential tourist attraction, the Ramparts of Vannes are among the few urban fortifications still remaining in Brittany.

History

First enclosure

At the end of the 3rd century, under the threat of Germanic peoples, the Emperor Probus authorized Darioritum, like all the cities of the Saxon Shore, to raise fortifications. The ancient town of Vannes thus surrounded itself with ramparts on the Mené hill and abandoned the Boismoreau hill, which formed the heart of the city.[1] The choice of this location was due to its configuration: the Mené hill was at that time a rocky promontory surrounded by marshes.[2] This first enclosure was roughly triangular and extended from the current rue du Méné, in the north, to the Place des Lices, in the south. More precisely, it was an “irregular hexagon comprising three large sides, of unequal lengths, connected to each other by three small sides, also of unequal lengths”.[3] This first enclosure, with a perimeter of less than 1,000 metres (3,300 ft), encompassed approximately 5 hectares.[note 1]

Sources then dry up for the following centuries. What is certain is that a fortress is attested in the 10th century on the northern wall. Some sources mention the 5th or 6th centuries as a possible period for its construction, as it seems that Eusebius of Vannes, semi-legendary king of Vannes, was already using this castle as a residence at the beginning of the 6th century.[4] This fortress was named Château de la Motte. Its etymology is not settled: perhaps due to its dominant position over the city or due to significant earthworks during construction.[4] The Château de la Motte later became the residence of the counts of Vannes, then of some of the kings and dukes of Brittany, including Macliau, Waroch II, Nominoë, John I, and Peter Mauclerc.

.jpg)

The incessant wars of the duke with his neighbors during the XII weakened the ramparts. Thus, the city was besieged five times between 1156 and 1175, twice by Henry Plantagenêt (in 1168 and 1175)[1]. As a result, Duke John I decided to undertake the restoration of the ramparts starting in 1237. The earthquake of 1287 prompted his successor, John II, to continue the work, which was completed in 1305. The Château de la Motte, too damaged by the earthquake, was then ceded to the bishop Henri Tore. He decided to rebuild it starting in 1288 to make it the episcopal manor of la Motte, the residence of the city’s bishops[1].

In 1342, during the War of the Breton Succession, the city endured four more sieges, changing hands several times between the party of Charles of Blois, supported by the French, and that of John of Montfort. The Vannes residents, who declared themselves in favor of John of Montfort in 1341, surrendered to the army of Charles of Blois at the beginning of 1342, but an English army, commanded by Robert III of Artois, retook the city in August. A few days later, Olivier de Clisson recaptured the city for the French after another siege in which Robert d’Artois was mortally wounded. The city successfully resisted a final siege led by Edward III in November[4].

Access to the walled city during the High Middle Ages was through five gates: Saint-Patern, Saint-Salomon, Bali, Saint-Jean, and Mariolle[5].

The Second Enclosure

After the war, John IV, son of John of Montfort, designated Duke of Brittany by the Treaty of Guérande, repaired and expanded the ramparts southward to encompass the city’s suburbs. The area of the walled city then increased from 5 to 13 hectares[6]. Two gates and their barbicans, Calmont and Gréguennic, were added to the enclosure; the city also acquired three towers around the mid-15th century: the Executioner’s Tower, the Powder Tower, and the Joliette Tower[5]. The work was not fully completed until the reigns of John V and Francis II[2].

John IV added to this reinforcement of the city’s defenses the construction of his new residence, the Château de l’Hermine, built between 1380 and 1385. To do so, he exchanged the mill he owned at Pencastel (Arzon) for the one at Garenne, belonging to the Abbey of Saint-Gildas de Rhuys[4]. As evidence of the growing importance of this new residence, births and marriages took place there at the end of the century and the beginning of the next: John V was born there in 1389[7], and Joan of Navarre married Henry IV of England by proxy there in 1402[1]. It became the near-permanent residence of the subsequent dukes until Francis II, who preferred staying in Nantes, where he had a new château built. The Château de l’Hermine then became a place of refuge or detention, depending on the duke’s will and the status of his “guests”: a residence for Charles of France in his struggle against his brother Louis XI between 1466 and 1467, or for Henry Tudor in 1483–1484, and a prison for Guillaume Chauvin, former chancellor of Brittany, between 1481 and 1484[1].

.png)

The war reignited a few years later, and the city was besieged and captured five times between 1487 and 1490[8]. The Breton defeat in this war marked the end of Breton independence, formalized nearly forty years later, on 4, with the request of the Estates of Brittany, at the Château de la Motte, to the King of France Francis I for the union of Brittany to France[9]

This miniature by Jean de Wavrin depicts the second capture of Vannes in 1342 by John of Montfort and the English camp. The battle takes place in the city’s moats between the Powder Tower and the Prison Gate. Anachronistic since these elements were built after 1430 and the Romanesque tower of the cathedral in the background was rebuilt only after 1450, this depiction is nevertheless faithful to the ramparts of the mid-15th century. The soldiers’ weapons (swords and bows) are typical of the mid-14th century, while the arrow slits are adapted to artillery fire (mid-15th century).[2]

Final reinforcements to partial dismantling

.png)

The integration of Brittany into the Kingdom of France brought a certain calm, both economic and military. The utility of the ramparts became less certain, but the city continued to maintain them to some extent in the 17th century, although the demolition of the Château de l’Hermine was decided during this period.[4]

At the end of the 16th century, during the Wars of Religion, several strategic cities in Brittany adopted the principle of bastioned fortifications, a necessity due to improvements in artillery. Under the Catholic League, Vannes sided with the Duke of Mercœur, governor of Brittany and a Leaguer. During his stay in Vannes in 1592, he employed his engineers and architects to improve the city’s fortifications.[2]. The city then strengthened the ramparts with the bastions of Gréguennic, Brozillay, and Haute-Folie in the southeast of the enclosure[5]. To the south, an opening was made for communication with the port. This was the Kaër-Calmont gate, which became the Saint-Vincent gate a few decades later. Between 1594 and 1598, Spanish troops were stationed in the city at the request of the Duke of Mercœur and the governor of Vannes, René d’Arradon. The city’s coffers were empty, and the work remained unfinished by the end of the 16th century[2]

After the failure of the League, Vannes suffered the repercussions of political instability and events along the Atlantic coast. Although the city no longer had a strategic role, its enclosure received final defensive improvements in the early decades of the 17th century. The bastions hastily erected under the League were improved between 1611 and 1619. Jean Bugeau rebuilt the Notre-Dame bastion in stone. The Haute-Folie bastion was rebuilt using piles by André Bugeau. The Saint-Salomon gate was also supposed to receive a bastion, but the project was abandoned.

.jpg)

Between 1622 and 1624, Jean Bugeau was in charge of the construction of the bridge and the Kaër-Calmont (Ker-Calmont) gate. The work was completed in 1624, and the gate was renamed Saint-Vincent Gate in homage to the preacher Saint Vincent Ferrer, who died in Vannes in 1419. The Garenne spur, intended to protect the passage of the Poterne gate, was built by the Vannes architect Antoine Angueneau between 1626 and 1628 after the withdrawal of the Nantes architect Jacques Corbineau.

Vannes experienced urban expansion in the second half of the 17th century, thanks to strong economic and religious growth and the establishment of the Parliament of Brittany in the city between 1675 and 1689. To accommodate the steadily increasing population and facilitate movement within the intra-muros, the city undertook various developments. With the construction, between 1678 and 1688, of the Poterne and Saint-Jean gates by the architect François Cosnier, the city now had six gates.

.png)

The bishop Charles de Rosmadec rebuilt the manor of la Motte starting in 1654[4], but in 1688, its dismantling was decided. In 1697, the remains of the Château de l’Hermine were donated to the city by the King of France Louis XIV. These, along with the sections of the wall being demolished, served as a quarry for the restoration of municipal buildings[4]. At the end of the 18th century, the city planned the destruction of parts of the ramparts to prevent the risk of collapse of the least well-maintained elements and to widen traffic routes. In 1784, the Notre-Dame gate and part of the bastion of the same name were demolished. During the Revolution, in 1791, the Saint-Salomon gate collapsed.

Julien Lagorce, a caterer, purchased the site of the former Château de l’Hermine to build a hotel in 1785[4]. In 1791, the manor of la Motte was abandoned by the bishop of the time, Sébastien-Michel Amelot. Nine years later, the Morbihan prefecture services moved in. However, poorly maintained, it continued to deteriorate. A section of the wall collapsed in 1860, prompting the departure of the prefectural services, which moved to the current building in 1865.

During the 19th century, the city implemented the embellishment plan drawn up in 1785–1787 by the engineer Maury. The development of Place Gambetta concealed the ramparts on either side of the Saint-Vincent gate. Other sections of the walls were demolished to allow the creation of new streets. The rue Le Mintier de Lehélec was opened in the west in 1826–1827. The manor of la Motte was razed shortly afterward, along with the entire northern part of the walls, during the opening of rue Émile Billault (1862–1867)[4]. Part of the manor survived in the Hôtel de France until its complete demolition in 1912.

The alignment of the port’s moats and the creation of rue Thiers between 1870 and 1900 led to the destruction of the ramparts between the Saint-François tower and the Haute-Folie bastion, including the Brozillay bastion. In 1886, the southern part of the Prison gate was demolished.

Protection and heritage

With nearly three-quarters of its ramparts preserved and despite the destruction of several segments in the 19th century, the urban enclosure of Vannes is one of the best-preserved in Brittany. The catalyst for raising awareness among the people of Vannes was, in 1911, the rumor of the complete destruction of the Prison Gate, which had already been partially demolished in 1886 to widen the street.

People from Vannes, attached to their heritage, came together to found, as early as 1911, Société des Amis de Vannes, an association dedicated to defending the city’s heritage. Its actions (starting with the launch of a public subscription, which raised 5,000 gold francs, donated to the Municipality at the time) enabled the city to purchase the gate and ensure its preservation.[10]

Thus, the listing in 1912 of the Prison Gate as a historical monument initiated a policy of protecting the ramparts. This was soon followed by the listing of the entirety of the city’s fortified heritage, with the process concluding in 1958 with the protection of the Gréguennic Bastion. As early as 1950, the mayor, Francis Decker, had the idea of creating a French-style garden to enhance the eastern part of the wall, which had previously been left fallow[11]. The safeguarding and enhancement plan has, since 1982, served as a tool for protecting the safeguarded sector of the old town, a policy supported by the signing of the French Towns and Lands of Art and History convention between the city and the Ministry of Culture.

The protection and enhancement of the ramparts take several forms, from numerous restoration projects to the hosting of exhibitions (Connétable Tower, maritime photography festival, etc.), as well as the establishment of the Institut culturel de Bretagne and numerous associations in the Hôtel Lagorce (known as Château de l’Hermine), fireworks, light projections, and the organization of events at the foot of the ramparts (book fair, historical festivals, Festival d'Arvor, Photo de Mer exhibition).

| Protected elements | Protection | Date |

|---|---|---|

| Porte Prison and tower | classement | 2 May 1912 |

| Éperon de la Garenne | inscription | 10 December 1925 |

| Tour Trompette and section of the ramparts | inscription | 23 May 1927 |

| Tour du Connétable and section of the ramparts | classement | 28 May 1927 |

| Tour du Bourreau and eastern section of the old ramparts | classement | 29 July 1927 |

| Old ramparts; porte Calmont | classement | 29 July 1927 |

| Section of the ramparts, near the Tour Joliette | classement | 16 May 1928 |

| Porte Poterne; terrace and section of the ramparts | classement | 28 July 1928 |

| Areas between the ramparts, Porte-Poterne street and Garenne stream | classement | 28 July 1928 |

| Porte Saint-Vincent | classement | 11 October 1928 |

| Base of the left tower flanking the Porte Prison | classement | 24 March 1936 |

| Part of the Porte Prison acquired by the town | classement | 30 November 1936 |

| Section of the ramparts | classement | 15 January 1942 |

| Part of the ramparts running from the Porte Prison to the Porte Saint-Jean | classement | 26 November 1956 |

| Porte Saint-Jean, Brizeux street | classement | 26 November 1956 |

| Tour Poudrière and adjoining parts of the ramparts | classement | 26 November 1956 |

| Part of the ramparts running from the Notre-Dame bastion to rue Saint-Salomon | classement | 26 November 1956 |

| Walls adjoining the Notre-Dame bastion, rue Emile-Burgault | inscription | 27 November 1956 |

| Haute-Folie bastion; Gréguenic bastion and its gate; curtain wall linking these two bastions | inscription | 7 March 1958 |

| Tour Saint-François, part of the adjoining ramparts and part of the “Sarrazine” walls | inscription | 7 March 1958 |

Detailed plan

Surviving elements

The elements listed below are described in clockwise order starting from the Notre-Dame Bastion, located at the northwest of the first enclosure. Not all elements of the ramparts are owned by the city of Vannes and are not accessible during guided or free visits. The ramparts are not entirely visible from public thoroughfares. Many elements are integrated into the urban landscape. "Using a rough estimate, it can be said that the ramparts of Vannes are destroyed for one-third, hidden for another third, and visible for the final third".[6][12]This estimate is rough and likely refers to the first enclosure. The city retains three-quarters of the second enclosure.

First enclosure

Notre-Dame Bastion

During the Catholic League, at the end of the 16th century, a bastion was built to protect the Notre-Dame Gate.[13] It was rebuilt between 1616 and 1618 by the architect Jean Bugeau. During the opening of Billault Street between 1865 and 1866, the northern flank of the bastion was destroyed. The southern flank, still visible, is equipped with two large firing embrasures. In 2014, the city acquired number 29 Émile Burgault Street, followed by number 27 in 2019, to demolish the buildings concealing part of the bastion, thereby enhancing its visibility and making it accessible to the public.[14]

The section of the ramparts from the Notre-Dame Bastion to Saint-Salomon Street, as well as the section adjacent to the bastion on Émile-Burgault Street, have been listed as historical monuments since 26 and 27, respectively.[15]

Saint-Jean Gate

The Saint-Jean Gate takes its name from the nearby chapel of the same name, located close to the Saint-Pierre Cathedral, which was demolished in 1856.[16] Closed before 1358, it was reopened in 1688 by the Vannes architect François Cosnier.[2] It was known by the names Porte du Mené, Porte du Bourreau (due to its proximity to the Executioner’s Tower), Porte du Nord, and Porte de l’Âne. The upper part of the gate features a stone plaque installed by the Amis de Vannes in 1911 or 1912, following a long-standing wish of the Estates of Brittany to place above this gate the coat of arms of France, surrounded by the coats of arms of the Duke of Chaulnes, Governor of Brittany, Lavardin de Beaumanoir, lieutenant general in Rennes, the Count of Lannion, Governor of Vannes, and finally, those of the city of Vannes.[17]

The section of the ramparts from the Prison Gate to the Saint-Jean Gate, as well as the Saint-Jean Gate itself, have been listed as historical monuments since 26.

Executioner’s Tower

.jpg)

This tower, equipped with Breton machicolations with arches on corbels, formerly known as the Tour des Filles because it served as a prison for women, was modified after the construction of the second enclosure. Built on foundations dating from the 14th century, the tower was completed in the mid-15th century. The name Executioner’s Tower comes from its use as housing for the city’s sworn executioner.

The Executioner’s Tower, or Tour des Filles, and the portion of the old ramparts extending eastward have been listed as historical monuments since 29.

Prison Gate and tower

The gate, built in dressed granite, features a round tower flanked by a rectangular building. It is characterized by a cart gate under a pointed arch and a pedestrian passage, diverted in a chicane.[18]

A fortified gate at the northeast of the city’s ramparts, the Prison Gate is one of the oldest entrances to the walled city. Built in the 13th century under the reign of Duke John II, it was named the Saint-Patern Gate, after the district it served. In the second half of the 14th century, under Duke John IV, the gate was equipped with a tilting drawbridge, a postern for pedestrian passage, and a large, lowered discharge arch. His successor, John V, continued the work, which included rebuilding the upper parts with Breton machicolations with pointed arches on corbels, constructing a barbican, and adding cannon ports. The fortified gate was operated by a double drawbridge system, one for the cart gate and one for the pedestrian passage.[19] In the 15th century, a now-deteriorated coat of arms (defaced during the French Revolution), likely bearing the arms of Brittany, was inserted between the drawbridge grooves. During the French Revolution, suspects and convicts were imprisoned there, including refractory clergy and priests, such as the Blessed Pierre-René Rogue, and royalists, such as the leadership of the émigrés who landed at Quiberon in 1795. The gate then took the name Prison Gate. Following the construction of a new prison, the gate and towers were sold to a private individual in 1825. The second half of the 19th century saw the alienation of the structure to private owners who often lacked the means to maintain it. The southern tower was demolished in 1886 (except for part of its ground floor and the outer facing of its lower level) to make way for a revenue building.

The Prison Gate and its adjacent tower, threatened with destruction, led to the founding of the Amis de Vannes, which had them listed as historical monuments on 2 and prompted the city to purchase them on 25 June 1912. The base of the left tower flanking the Prison Gate has been listed since 24, with this part acquired by the city on 30. It has since undergone several restoration campaigns. Between September 2010 and early 2012, works including "the restoration of exterior masonry, interior facings, joinery, sculptures above the cart gate, as well as selective repairs to openings and waterproofing of the curtain walls and remains of the southern tower" were carried out.[20]

Joliette Tower

The Joliette Tower was rebuilt in the second half of the 15th century, replacing an older tower constructed at the end of the 12th century. Part of the northern curtain wall adjacent to it rests on the original Gallo-Roman wall. Embrasures were added to the tower to accommodate artillery pieces: two archer-cannon ports at the lower level, served by a long straight staircase.[2]

The section of the ramparts, including the Joliette Tower, has been listed as a historical monument since 16.

Poudrière Tower

Like the Joliette Tower, the Poudrière Tower was rebuilt in the second half of the 15th century on the foundations of an earlier 12th-century tower. This tower, equipped with artillery casemates (two cannon ports served by a straight staircase and a return), was used at the end of the Middle Ages as a storage for gunpowder, earning it the name Poudrière. The section of the curtain wall between the Joliette and Powder Magazine Towers is the only part permanently accessible to the public, with entry via Vierges Street.

The Poudrière Tower and its adjacent rampart sections have been listed as historical monuments since 26.

Second enclosure

Connétable Tower

This large tower is located on the flank of the city’s ramparts facing the Garenne plateau. The Connétable Tower was erected in the mid-15th century, during the expansion of the intra-muros area of Vannes. Situated near the Château de l’Hermine, this tower may have been part of its defenses. Although the tower has artillery casemates in the lower chamber, its primary function was as the residence of the connétable, the commander of the duke’s armies. The name Connétable Tower thus derives from its role as the residence for the city’s connétable or possibly because it housed Arthur III, Connétable de Richemont. The tower, standing 20 metres (66 ft) tall, is built on five levels and is flanked by two staircases. The two main rooms are illuminated by large openings, including two stone-mullioned windows facing south. The pointed roof is topped by a chimney. The tower was likely part of an unrealized residential project, as evidenced by the presence of unfinished masonry on the intra-muros side toward the Place des Lices.[21] A postage stamp depicting the illuminated ramparts and the Connétable Tower was issued on 26 with a first day of issue cancellation on the 24th in the city.[22] The Connétable Tower and adjacent rampart sections have been listed as historical monuments since 28.[23]

-_2010.jpg)

Garenne Spur

Vannes decided to reinforce its enclosure one final time in 1625 with the construction of a bastion between the Connétable Tower and the ruins of the Château de l’Hermine. A project was proposed by Jacques Corbineau, an architect from Laval, but it was the architect Antoine Augereau who completed the work between 1626 and 1628. The Garenne Spur is located just north of the Poterne Gate. Shaped like an ace of spades, it features a large casemate opening to the north. Two firing embrasures allowed artillery to enfilade the entire curtain wall of the Connétable Tower. At its base are the old wash houses and some stone houses.[24]

The Garenne Spur has been inscribed as a historical monument since 10.

Poterne Gate

Access to this fortified gate is via a small stone bridge that serves as a sluice for the Vannes river, the Marle River. The gate was opened between 1678 and 1680 by Cosnier, during the city’s embellishment period.[2] In the 18th century, its arch was broken to widen the passage. A small niche above the gate houses a copy of a 17th-century polychrome wooden statue of the Virgin. The original is kept in the Musée de la Cohue.[25] The Poterne Gate, terrace, and portion of the ramparts have been listed as historical monuments since 28.

Hôtel Lagorce

The Hôtel Lagorce is one of the rampart elements not part of the fortified systemThe fortified system was completed with the construction of the Garenne Spur in 1628. This private mansion, integrated between two curtain walls, was built on the ruins of the former fortress of Duke John IV. Gradually abandoned, the château was used as a quarry starting in the 18th century. Its foundations were leased in 1785. The city community granted the land containing the château ruins on 18, with the leasehold deed signed on 14. to Julien Lagorce, a Vannes caterer who built a private mansion in place of the former ducal residence. Financially ruined, Lagorce sold the mansion in 1802 to M. Castellot, a merchant from Lorient. The Hôtel Lagorce, later known as Castellot and then Jollivet-Castellot, was sold again to a Vannes entrepreneur who, after restoring and raising it in 1854, transferred it in 1874 to the State to house the General Staff of the artillery school.[26] The east wing of the mansion underwent renovations to be converted into classrooms. The partition walls were removed, and metal beams were installed to reinforce the building’s structure. In 1960, the mansion became the headquarters of the Public Treasury administration until 1974, when the city of Vannes acquired it to establish the Morbihan law school. Since 2003, it has been the headquarters of the Institut culturel de Bretagne and houses the offices of several associations. Until 2010, it also housed the library of the Société polymathique du Morbihan. In 2006, the ground floor rooms were fully modernized to host exhibitions. The memory of the former ducal fortress remains strong, and the Hôtel Lagorce is today better known as the Château de l’Hermine.

Calmont Gate and tower

_-_2010.jpg)

This fortified gate and the partially demolished tower flanking it date from the 14th to 15th centuries. It owes its name to the fact that this gate allows passage between the walled city and the Calmont district, located southeast of the city center. The double passage (cart and pedestrian) was controlled by drawbridges with arrows and protected by machicolations, now gone. The third level of the tower was razed and had the same characteristics as the Trumpet Tower: the upper chamber, located under a pointed roof, was surrounded by a covered walkway resting on machicolation corbels.[27] To the right of the gate, at the top of the curtain wall, corbels can be seen that supported a guardhouse built in an overhang above the moat.

_-_2010.jpg)

Under the cart gate, a recess is noticeable, which housed a concealed door. Hypotheses suggest this opening was either an escape route or a dock for small boats. At the base of the tower is the entrance to the underground canal of the Marle, which passes under Place Gambetta to the port.

After the opening of the Saint-Vincent Gate, completed in 1624, the Calmont Gate was closed. In 1681, a structure was built opposite the gate to support a sluice controlling the flow of the Marle toward the port. In the 18th century, a Vannes family turned the northern curtain wall into a small promenade leading to a pavilion located against the Hôtel Lagorce. During the gate’s restoration in 1992, the chief architect of historical monuments authorized the installation of a fixed bridge made of wood supported by a metal structure to restore passage between the intra-muros and a small shaded square with views of the Hôtel Lagorce and the ramparts’ gardens.[28] In 2008, the outer facing of the curtain wall between the Calmont Tower and the Hôtel Lagorce was restored.[2] In 2010–2011, waterproofing works on the curtain wall’s ground were carried out. In 2018, the poor condition of the wooden footbridge leading to Bertrand-Frélaut Square caused the temporary closure of the Calmont Gate. Works to completely restore the footbridge were carried out in early 2019. The wooden guardrails were replaced with wrought iron. Alongside the footbridge restoration, further restoration work was undertaken, including repointing the base of the gate’s parapet, paving the Trumpet Tower alley, and removing a step under the gate to make the passage between Bertrand-Frélaut Square and Saint-Vincent Street accessible to people with reduced mobility.[29]

The Calmont Gate has been listed as a historical monument since 29.[30]

.jpg)

Trumpet Tower

This tower was named after the herald, the city’s trumpeter, who used it as a residence. It appears to date from the 14th century for its base and the second half of the 15th century for its upper levels.[31] "The row of corbels forming machicolations supports the crenelated parapet on which the covered walkway’s roof rests".[2] It was set on fire by the Spanish in 1597,[32] a troop of 3,000 men sent by their king to assist Philippe-Emmanuel de Lorraine, Duke of Mercœur, governor of Brittany, during the Catholic League episode. This event earned it the nickname Burnt Tower.

The Trumpet Tower has been inscribed as a historical monument since 23.

Saint-Vincent Gate

At the end of the 16th century, an opening was made in the southern ramparts for communication with the port: the Kaër-Calmont GateNamed after the suburbs it served: Kaër to the southwest and Calmont to the southeast.. Between 1620 and 1624, Jean Bugeau was tasked with constructing the bridge and the Kaër-Calmont (or Ker-Calmont) Gate. Upon completion, the gate was renamed Saint-Vincent Gate in homage to the preacher Saint Vincent Ferrer, who died in Vannes in 1419. The gate replaced fortifications from the 14th to 16th centuries, of which a bastion remains behind the left side of the square: the Gréguennic Bastion. It is a classical structure with columns and niches in full arch.

Successive tides of the gulf damaged the gate’s base, and its structure showed severe deterioration by the early 18th century. The gate was repaired for the first time in 1727. A reconstruction project was initiated in 1738, but the architect Jannesson’s plans were not executed. The gate was entirely rebuilt in 1747 by the engineer Duchemin, who retained the facade designed by Bugeau but removed the roof and upper chamber.[33]

In the central niche, a statue from 1891 of Saint Vincent Ferrer recalls the importance of this preacher in Vannes’ history. The city’s arms were carved in granite at the same time. The original statue of the saint, installed in 1624 and crafted in Nantes by the Vannes painter Guillaume Lemarchand,[34] was replaced during the French Revolution by that of a sans-culotte and has since disappeared. A legend claims that when the saint’s statue lowers its hand, the city will be submerged by water.

The Saint-Vincent Gate is a "dressed granite gate structured with three bays framed by columns and three levels. At the lower level, the cart gate is flanked by two narrow bays, one blind and the other with a pedestrian door. Two niches open at the second level in the lateral bays, framing the city’s arms. The third level consists of a central niche framed by volutes.".

In late 2014, maintenance and restoration work on the gate, both extra- and intra-muros, was carried out, along with the restoration of the Saint Vincent statue.

The Saint-Vincent Gate has been listed as a historical monument since 11.

Gréguennic Gate and bastion

_-_2010.jpg)

Texts from the 14th to 15th centuries mention a fortified gate, the Gréguennic Gate, dating from the period of the enclosure’s southern expansion. The Gréguennic Gate, along with the Calmont Gate, is one of the two gates opened in the south following the extension of the enclosure. The gate provides access to the port and “consists of two towers projecting from the wall”.[2] Only the ground floor of the eastern tower and the adjacent curtain wall of the western tower are equipped with arrow slits.[2] Originally, the gate was protected by a simple portcullis with a counterweight. A barbican, “served by a fixed bridge on the city side and a drawbridge with arrows on the sea side”, was added to reinforce the gate in the early 15th century.[2] At the end of the 16th century, the enclosure was strengthened by the addition of bastions such as the Gréguennic Bastion, whose construction was initiated under the governance of Duke of Mercœur. The barbican disappeared, and although almost entirely preserved, the gate lost its role as an entrance to the walled city.

_-_Tour_est.jpg)

The site’s renovation starting in 1992 cleared this four-sided bastion, completed in 1593,[2] and built to defend the moat and the port. The old towers and the Gréguennic Gate were largely preserved. The tower has two firing embrasures. Five casemates are arranged in a battery within the thickness of the western wall, along a narrow corridor.[2] Each casemate, except the central one which has two, is pierced with a single firing embrasure and a vent hole for evacuating cannon smoke. Only the southwest side lacks a firing embrasure. Cannons placed on the walkway reinforced the firing plan of the ground floor.[2]

Access to the bastion is via the former gate, which must have been significant given its multiple expansions, closures, or heightenings before being replaced by the Saint-Vincent Gate in the 17th century.[35] Today, the bastion is entirely concealed by the layout of Place Gambetta and the intra-muros. The installation of a glazed floor in the covered passageThe Gréguennic Bastion is accessed via a covered passage located on the ground floor of a residential building on the intra-muros side. between Place de la Poissonnerie and the bastion allows observation of remnants of the old structures.

The Gréguennic Bastion has been inscribed as a historical monument since 7.[36]

Haute-Folie Bastion

Built during the troubled period of the French Wars of Religion, the Haute-Folie Bastion was originally made of earth and turf and equipped with a drawbridge. The bastion was completed by André Bugeau in 1618 “following the principle of masonry on piles driven into the mud”.[2] In the 18th century, like its neighbors, it took the name of its occupant and became the Gaumont Bastion. It is now concealed by the buildings on Thiers and Carnot Streets to the west and Place de la Poissonnerie to the east.[4] The Haute-Folie Bastion has been inscribed as a historical monument since 7.

Saint-François Tower

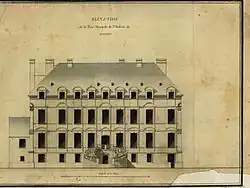

_1785.jpg)

This tower was built in the late 14th century during the southern extension of the enclosure. It takes its name from the Franciscan (or Cordeliers) convent, founded by John I in 1260. The only convent located within the city walls due to its early establishment south of the first enclosure, it bordered the eastern part of the ramparts, of which the tower is a component.

The adjacent plan depicts the project to create a street passing through the Cordeliers convent. Drawn in 1785 by Detaille de Keroyand, a civil engineer, it shows part of the western walls and moats, the Brozillay Bastion, the Saint-François Tower, and the Saint-Salomon Gate. The Le Mintier de Lehélec Street was only created between 1826 and 1827. During the alignment of the port’s moats between 1870 and 1900, part of the Saint-François Tower and the curtain wall up to the Haute-Folie Bastion were destroyed, leaving only its base.

The Saint-François Tower (including adjacent ramparts and part of the so-called Saracen walls) has been inscribed as a historical monument since 7.

Disappeared elements

First enclosure

Notre-Dame Gate and tower

Located near the Château de la Motte, the gate was one of the fortifications of the first seat of the counts of Vannes. A statue of Notre-Dame was placed at the top of this gate, with a small roof or canopy surmounting it, hence its original name, Porte du Bali.[37] This old gate was renovated during the 15th century and equipped with a tower. The construction of the Notre-Dame Bastion at the end of the 16th century led to the creation of a new gate to the west of the older one and the absorption of the nearest tower into the bastion. Until its destruction in 1784, the new gate was also called Porte Neuve. The gate was located west of the current Émile Burgault Street, opposite the town hall.

All that remains of this gate is a sentry turret overlooking Émile Burgault Street.

Château de la Motte

The oldest known residence of power in the city, the Château de la Motte was adjacent to the Notre-Dame Tower in the northern part of the enclosure, on the highest point of the city. This castle was built around the 5th or 6th century and is believed to have been the residence of King Eusebius at the beginning of the 6th century[4], although some sources suggest a later construction date (9th or 10th century). Before the castle was ruined by the Normans in the early 10th century, this fortress was the residence of the counts of Vannes. Restored by the dukes, it was temporarily inhabited by Peter Mauclerc and John I. Damaged by the earthquake that struck Vannes in 1287, Duke John II, who preferred the Château de Suscinio, ceded La Motte to Henri Tore, the bishop of the city. The structure was rebuilt starting in 1288. The castle then became the episcopal manor of La Motte.

In 1532, the episcopal manor hosted the congregation and assembly of the Estates of Brittany in the presence of King Francis I. It was in the great hall of the manor that the request for the union of Brittany with France was deliberated: the Lettre de Vannes.

The manor was rebuilt again at the initiative of Monseigneur Charles de Rosmadec in 1654. The work lasted 18 months (1.5 a). Further works were carried out by Louis Cazet, and his successor, François d’Argouges, acquired the northern moats, known as du Mené, in 1688, converting them into a large garden. Sébastien-Michel Amelot was the last bishop to reside there, abandoning La Motte in 1791 due to his refusal to swear allegiance to the Civil Constitution of the Clergy.

After the Revolution, Vannes was chosen as the capital of the new Morbihan department. The department’s directorate was established there in 1793. The first prefect, Henri Giraud Duplessis, settled at La Motte in March 1800. The castle remained the prefecture’s seat for 60 years (1,900 Ms). On 11, a retaining wall collapsed, killing two people. The Ministry of the Interior sent an architect from the civil buildings council, who concluded that repairs were impossible, and the structure was reinforced with iron to prevent total collapse. The manor and its dependencies were sold in 1866 for 110,000 francs.[4] The castle was partially demolished in 1867, allowing the construction of a new road to the station: Billault Street. The Hôtel de France, demolished in 1912,[38] retained two facade windows on each floor.[4]

Second enclosure

Château de l’Hermine

The Château de l’Hermine is a defensive and residential building commissioned by Duke John IV, who sought to benefit from the more central position of Vannes in his duchy. The fortress was accompanied by extensive dependencies where he created a park, with the grounds extending from the Garenne to the Étang au Duc. According to the Froissart's Chronicles, it is “very beautiful and very strong”,[39] and for Bertrand d’Argentré in his Histoire de Bretagne, dated 1582, “it is a small building for a prince, consisting of a single residential structure and many small towers, with two large towers on the outside”.

The construction of this building took place between 1380 and 1385, with the work continuing until the mid-15th century. The duke’s household services were located in the bailey: the mint workshop, the oven house, the tennis court, and the ducal stables.[1] The extent of this was revealed by excavations conducted at the end of the 20th century. The construction of the Lices mill, the chamber of accounts, and the Lices chapel between 1420 and 1425 completed the complex.

The integration of the duchy into France in 1532 left it without maintenance. Given to the city by Louis XIV in 1697, it then became the site of a quarry used for the restoration of municipal buildings and the development of the port.

Saint-Vincent Bridge

.jpg)

Little is known about the existence of a passage between the Kaër land to the west and Calmont to the east before the opening of the Saint-Vincent Gate. A document mentioning the repair of a bridge in 1598 is the first evidence of a passage between the two banks of the port.[40] The bridge is not strictly part of the fortifications but is an essential urban element facilitating access between the city and the port.

The bridge had to be modified following the construction of the Billy quay in 1697. In 1787, the city embellishment project designed by the engineer Maury planned the creation of a square between the gate and the port’s end, but the French Revolution halted it. The project was revived by the municipal council in 1835, and the city architect Philippe Brunet-Debaines was tasked with its realization. Marius Charier took over the project after Brunet-Debaines’ death in 1838. In 1843, the construction of the square, the buildings on the former mudflats on either side of the bridge, and the underground Marle canal were completed. The Place du Morbihan (later Place Gambetta) replaced the Saint-Vincent Bridge. In 1976, during the square’s refurbishment, the remaining arches were broken open; roadworks in 2005 revealed the presence of one last intact arch.

Michelet Gate

Opened during the expansion works at the end of the 14th century, the Michelet Gate was located northwest of the Gréguennic Gate. It disappeared during the construction of the Haute-Folie Bastion at the end of the 16th century.

Brozillay Bastion

The Brozillay Bastion, or Ker Bastion, the third bastion built during the Catholic League, had the same technical characteristics as the Gréguennic Bastion. Built in masonry, it is a “hollow bastion equipped with a low battery and spaced casemates along the curtain wall. [...] At each corner of the structure, a sentry turret on machicolation corbels serves as a lookout post”.

In the 18th century, like its neighbors, it took the name of its owner and became the Bavalan Bastion, behind the hotel of the same name. Between 1870 and 1900, during the opening of Thiers Street, the curtain walls from the Saint-François Tower to the Haute-Folie Bastion, including the Brozillay Bastion, were destroyed.

Notes

- ^ According to the calculations of Jules de la Martinière (L'enceinte romaine de Vannes), this enclosure measured 917 metres (3,009 ft) for an encompassed area of 4.916 hectares. The work of Claudie Herbaut, Gérard Danet, and Christophe Le Pennec (Les remparts de Vannes, Découverte d'une ville fortifiée des origines à nos jours) mentions a perimeter of 980 metres (3,220 ft) for an area approaching 5 hectares.

References

- ^ a b c d e f Frélaut, Bertrand (2000). Histoire de Vannes [History of Vannes]. Les Universels Gisserot (in French). Jean-Paul Gisserot. p. 127. ISBN 978-2-877475273.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Herbaut, Claudie; Danet, Gérard; Le Pennec, Christophe (2008) [2001]. Les remparts de Vannes, Découverte d'une ville fortifiée des origines à nos jours [The ramparts of Vannes, Discovery of a fortified city from its origins to the present day] (in French). Animation du Patrimoine, Ville de Vannes. p. 52. ISBN 978-2-909299-29-7.

- ^ De la Martinière, Jules (1927). L'enceinte romaine de Vannes [The Roman enclosure of Vannes] (PDF) (in French). Rennes: Imprimerie Oberthur. p. 15. Retrieved 27 January 2010.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Le Mené, Joseph-Marie (1897). Topographie historique de la ville de Vannes [Historical topography of the city of Vannes] (in French). Galles. Retrieved 27 January 2010.

- ^ a b c "Vannes, urban enclosure". patrimoine.region-bretagne.fr. 2000. Archived from the original on 1 December 2023. Retrieved 23 January 2010.

- ^ a b Aquilina, Manuelle (2002). "Les remparts de Vannes : un patrimoine ignoré hier, médiatisé aujourd'hui" [The ramparts of Vannes: a heritage ignored yesterday, celebrated today]. Annales de Bretagne et des pays de l'Ouest (in French). 109 (1). Université de Haute-Bretagne, Rennes: 147–160. doi:10.4000/abpo.1633. ISSN 0399-0826.

- ^ "Jean Ier le roux". Larousse. Retrieved 23 January 2010.

- ^ "Étymologie et histoire de Vannes". infobretagne.com. Retrieved 23 January 2010.

- ^ "Édit d'union de la Bretagne et de la France". Rois & Présidents. Retrieved 23 January 2010.

- ^ "Porte-Prison". topic-topos. Archived from the original on 26 January 2012. Retrieved 23 January 2010.

- ^ "Lavoirs de la Garenne - Vannes, France". waymarking.com. 2007. Retrieved 23 January 2010.

- ^ Frélaut, Bertrand (1991). "Le mot du président" [The president's word]. Bulletin des amis de Vannes (in French) (16): 3–4.

- ^ "Patrimoine de Vannes" [Heritage of Vannes]. infobretagne.com (in French). Retrieved 23 January 2010.

- ^ "Vannes. La Ville rachète le kebab Chez Momo pour continuer à dévoiler ses remparts" [Vannes. The city buys the Chez Momo kebab shop to continue revealing its ramparts]. Ouest-France (in French). 5 February 2019. Retrieved 11 May 2019.

- ^ "Notice no PA00091806". Base Mérimée (in French).

- ^ Thomas-Lacroix, Pierre. Le Vieux Vannes [Old Vannes] (in French). p. 8.

- ^ "Porte Saint-Jean" [Saint-Jean Gate]. topic-topos (in French). Archived from the original on 4 September 2014. Retrieved 30 January 2010.

- ^ Mairie de Vannes. "Porte Prison en détail" [Prison Gate in detail]. mairie-vannes.fr (in French). Archived from the original on 2023-12-01. Retrieved 28 December 2016.

- ^ "Monuments incontournables" [Essential Monuments] (in French). Archived from the original on 23 January 2010.

- ^ Mairie de Vannes (2012). "Travaux de rénovation du patrimoine, La Porte Prison fait peau neuve" [Heritage renovation works, The Prison Gate gets a facelift]. mairie-vannes.fr (in French). Archived from the original on 2023-12-01. Retrieved 29 March 2012.

- ^ "Les monuments incontournables de Vannes" [Essential Monuments of Vannes]. Mairie de Vannes (in French). Archived from the original on 2023-12-01. Retrieved 23 January 2010.

- ^ Stamp issued in 1962

- ^ "Notice no PA00091806". Base Mérimée (in French).

- ^ "Éperon de la Garenne" [Garenne Spur]. topic-topos (in French). Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 30 January 2010.

- ^ "Porte-Poterne" [Poterne Gate]. topic-topos (in French). Archived from the original on 10 December 2014. Retrieved 23 January 2010.

- ^ Guyot-Jomard (1887). "Le Château de l'Hermine" [The Château de l’Hermine]. Bulletin de la Société polymathique du Morbihan (in French): 41.

- ^ Lefèvre, Daniel (1993). Porte Calmont, étude préalable à la restauration [Calmont Gate, preliminary study for restoration] (in French). Archives municipales de Vannes. p. 112.

- ^ "Tour et porte Calmont" [Calmont Gate and Tower]. topic-topos (in French). Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 30 January 2010.

- ^ "Vannes. Porte-Calmont : les travaux vont débuter" [Vannes. Calmont Gate: works to begin]. Le Télégramme (in French). 28 December 2018.

- ^ "Notice no PA00091806". Base Mérimée (in French).

- ^ Thomas-Lacroix, Pierre. Le Vieux Vannes [Old Vannes] (in French). p. 12.

- ^ "Patrimoine de Vannes" [Heritage of Vannes]. infobretagne.com (in French). Retrieved 9 January 2010.

- ^ "Porte Saint-Vincent" [Saint-Vincent Gate] (in French).

- ^ Furon, Olivier (1995). Vannes. Mémoire en images (in French). Éditions Alan Sutton. p. 20.

- ^ "Bastion de Gréguennic" [Gréguennic Bastion]. topic-topos (in French). Archived from the original on 24 January 2009. Retrieved 23 January 2010.

- ^ "Notice no PA00091806". Base Mérimée (in French).

- ^ Thomas-Lacroix, Pierre. Le Vieux Vannes [Old Vannes] (in French). pp. 8–9.

- ^ "Histoire de la préfecture" [History of the prefecture]. morbihan.pref.gouv.fr (in French). Archived from the original on 7 May 2010. Retrieved 7 February 2010.

- ^ Froissart, Jean. "LX". Chroniques [Chronicles] (in French). Vol. X.

- ^ "Pont Saint-Vincent, puis pont du Morbihan" [Saint-Vincent Bridge, then Morbihan Bridge]. patrimoine.region-bretagne.fr (in French). Archived from the original on 2023-12-01. Retrieved 26 March 2010.

Bibliography

- Herbaut, Claudie; Danet, Gérard; Le Pennec, Christophe (2008) [2001]. Les remparts de Vannes, Découverte d'une ville fortifiée des origines à nos jours [The ramparts of Vannes, Discovery of a fortified city from its origins to the present day] (in French). Animation du Patrimoine, Ville de Vannes. p. 52. ISBN 978-2-909299-29-7.

- *Frélaut, Bertrand (2000). Histoire de Vannes [History of Vannes]. Les Universels Gisserot (in French). Jean-Paul Gisserot. p. 127. ISBN 978-2-877475273.

- Le Mené, Joseph-Marie (1897). Topographie historique de la ville de Vannes [Historical topography of the city of Vannes] (in French). Galles. Retrieved 27 January 2010.

- Aquilina, Manuelle (2002). "Les remparts de Vannes : un patrimoine ignoré hier, médiatisé aujourd'hui" [The ramparts of Vannes: a heritage ignored yesterday, celebrated today]. Annales de Bretagne et des pays de l'Ouest (in French). 109 (1). Université de Haute-Bretagne, Rennes: 147–160. doi:10.4000/abpo.1633. ISSN 0399-0826.

- De la Martinière, Jules (1927). L'enceinte romaine de Vannes [The Roman enclosure of Vannes] (PDF) (in French). Rennes: Imprimerie Oberthur. p. 15. Retrieved 27 January 2010.

- Furon, Olivier (1995). Vannes. Mémoire en images (in French). Éditions Alan Sutton. p. 128. ISBN 2-910444-37-6.

- Guyot-Jomard, Alexandre (1887). "La ville de Vannes et ses murs" [The city of Vannes and its walls]. Bulletin de la Société polymathique du Morbihan (in French): 26–34. Retrieved 18 March 2010.

- Guyot-Jomard, Alexandre (1887). "Le Château de l'Hermine" [The Château de l’Hermine]. Bulletin de la Société polymathique du Morbihan (in French): 34–43. Retrieved 18 March 2010.

- Thomas-Lacroix, Pierre (1982) [1975]. Le Vieux Vannes [Old Vannes] (in French) (2 ed.). Vannes: Société polymathique du Morbihan. p. 155.

- André, Patrick (1987). "Le rempart de Vannes et la défense de la ville au Bas-Empire" [The rampart of Vannes and the city’s defense in Late Antiquity]. Bulletin des Amis de Vannes (in French) (12): 20–26.

- Aquilina, Manuelle (1998). Les remparts de Vannes du III au XX : de l'enceinte fortifiée à la simple ceinture de murailles [The ramparts of Vannes from the 3rd to the 20th century: from a fortified enclosure to a simple belt of walls] (in French). Rennes 2: CRHISCO, TH 316 AD56, TH 517. p. 179.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - Danet, Gérard (1992). Porte et bastion de Kaër-Gréguennic, étude historique et architecturale [Kaër-Gréguennic Gate and Bastion, historical and architectural study] (in French). Ville de Vannes.

- Decenneux, M. (1978). "Le château de l'Hermine à Vannes, résidence des ducs de Bretagne" [The Château de l’Hermine in Vannes, residence of the Dukes of Brittany]. Bulletin archéologique de l'Association bretonne (in French): 58–62.

- Galles, Louis (1856). "Les murailles de Vannes depuis 1573" [The walls of Vannes since 1573]. Annuaire du Morbihan (in French).

- Le Pennec, Christophe (1998). "Vannes au Bas-Empire : un castrum" [Vannes in Late Antiquity: a castrum]. Actes du colloque "Vannes et ses soldats" (in French). Arradon: CERSA, Université catholique de l’Ouest.

- Lefèvre, Daniel (1993). Porte Calmont, étude préalable à la restauration [Calmont Gate, preliminary study for restoration] (in French). Archives municipales de Vannes. p. 112.

- Pasquesoone, Lucie (2007). Richard, G. (ed.). Le secteur sauvegardé de Vannes : reflet des réussites et des contradictions des politiques nationales de protection du patrimoine depuis 1962 [The safeguarded sector of Vannes: a reflection of the successes and contradictions of national heritage protection policies since 1962] (in French). Rennes: IEP Rennes (political science thesis).

- André, Patrick; Degez, Albert (1983). "Vannes, topographie urbaine" [Vannes, urban topography]. Congrès de la Société française d'archéologie (in French). Morbihan, Paris: 288–293.

- De La Borderie, Arthur (1991) [1885–1894]. L'architecture militaire du Moyen Âge en Bretagne [Military architecture of the Middle Ages in Brittany] (in French) (New ed.). Mayenne: Rue des Scribes.

- Le Pennec, Christophe (1999). "Les enceintes urbaines (XIIIe - XIVe siècles)" [Urban enclosures (13th–14th centuries)]. Actes du 121e congrès des Sociétés historiques et scientifiques (in French). Nice: CTHS.

- Salamagne, A. (1999). Prigent (ed.). L'architecture militaire, châteaux et fortifications urbaines [Military architecture, castles, and urban fortifications] (in French). Paris: Maisonneuve et Larose. pp. 169–185.