Railton Road

Railton Road runs between Brixton and Herne Hill in the London Borough of Lambeth. The road is designated the B223. At the northern end of Railton Road it becomes Atlantic Road, linking to Brixton Road at a junction where the Brixton tube station is located. At the southern end is Herne Hill railway station. Squatted in the 1970s, it won renown in the Black community as the "frontline" of the 1981 Brixton riot. Its leading establishment is the 198 Contemporary Arts and Learning centre.

History

Origin

Railton Road in its present form dates from a renumbering and renaming of streets in 1888. This incorporated buildings that had started life as properties on Station Road[1] and Lett Street.[2] It was in this late Victorian period that the road developed as a residential street. Built in 1878, the St. George’s Residences, 78-80 Railton Road, (with a water tank in the central tower) is an early example of a purpose-built block of flats.[3]

Squatted road, 1970s

After the Second World War, in which the Blitz damaged and destroyed much of the local housing stock, Lambeth Borough Council used new compulsory purchasing powers to buy out the private landlords. A result was that, while plans for new public housing were being brought forward, properties on the road lay empty and in disrepair, contributing to an acute housing crisis in which West Indian immigrants and a growing Black community, in particular, found themselves crowded into substandard tenements.[4] Combined with a developing counter-cultural scene in London, these conditions opened Railton Road in the 1970s to extensive squatting.

In 1972, the British Black Panthers, Olive Morris and Liz Obi, occupied a flat above a launderette in Railton Road. After fighting off attempts at illegal eviction, and taking cue from a group of white women who had also moved into the road to run women’s centre, they opened a larger corner-shop building, 121 Railton Road. This became a centre, first for Black organisations including the Brixton Black Women's Group, and later for anarchists.[5] Others followed: by the mid-1970s there was a second women’s centre at number 80; next to it in 78, the South London Gay Community Centre (evicted 1976);[6] the collective producing Race Today, edited by Darcus Howe, whose uncle, the Trinidadian historian C. L. R. James, lived – and in 1989 was to die – at number 165 (now the Brixton Advice Centre);[7] a Claimants’ Union;[6] and, underneath her dress shop at 103, Pearl Alcock’s Shebeen (patronised by Caribbean gay men, it was closed by the police in 1979).[8][9]

1981 Brixton Riot and its aftermath

In 1981, Albert Meltzer, who established the Kate Sharpley Library (KSL) in the "121 Centre",[10] recalls the police doing "their best" to blame the onset of the Brixton riot on he and his fellow anarchists, but that this had been "rather difficult as the rioters were Black youths pushed by harassment".[11][5] The trigger to the riots, which began in Railton Road, is commonly ascribed to the police's increased use of stop-and-search and to tensions arising from the deaths of 13 black teenagers and young adults in a suspicious house fire in New Cross.[12]

In the riot, the George public house was burnt down and a number of other buildings were damaged, and the area became known as the "Front Line". In their search of the source of petrol bombs, police were accused of damaging homes, smashing televisions and ripping furniture.[13] The George was replaced with a Caribbean bar called Mingles in 1981, which lasted in one form or another (later called Harmony) as a late-night mostly Caribbean-British attended club/bar until the 2000s. Despite its reputation as run-down, violent and racially tense – a "no-go" area – it was a hotbed of Afro-Caribbean culture, radical political activity and working-class community. The 121 Centre, in which the anarchists later ran a bookshop, a cafe and a disco, and published their news sheet Black Flag, was one legacy of squatting in Railton Road survived until its heavily contested eviction in 1999.[11][14]

After the riot, the authorities had saturated the area with police and social workers, and demolished half of both Railton and Mayall Roads, clearing them of shops, homes and clubs,[15] although not without incident. In November 1982, following evictions from nine houses, riot squads broke through a makeshift barricade and batoned a large crowd of youths.[16] In advance of demolition, squatters who had held out around the corner, in Effra Parade, were turned out of their row of seven workers' cottages by a force of 200 police in 1984.[17]

21st century

In 1994, an organisation, originally named Roots Community, founded in 1988 by John "Noel" Morgan, a minicab driver and Zoe Lindsay-Thomas, manager of the Vargus Social Club in Landor Road,[18] established an arts centre at 198 Railton Road. 198 Contemporary Arts and Learning, also known as the 198 Gallery or 198, describes itself as a "Black-led, arts, creative and cultural organisation which nurtures and supports the careers of young Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic artists, curators, creatives and entrepreneurs".[19]

198 has hosted projects and solo exhibitions showcasing the work of more than four hundred British and international artists, including: Keith Piper, Eva Sajovic,[20] Hew Locke, Brian Griffiths, Fernando Palma Rodriguez,[21] Quilla Constance,[22] Barby Asante, Delaine Le Bas,[23] and Godfried Donkor [24] In 2022, it mounted a retrospective, "Coming Home", for the drawings and paintings of Pearl Alcock[25] who, after her shebeen was closed at 103, continued to run a cafe at 105 until, following the 1981 riot, her electricity was cut.[26]

On 30 October 2022, 21-year-old Deliveroo driver Guilherme Messias Da Silva, and 27-year-old Lemar Urquhart were killed as a result of a gang-related incident on Railton Road. Da Silva was fatally injured after his moped collided with a car being driven by Urquhart who was at the time of the collision being pursued by another vehicle. Urquhart escaped his car before being chased down and fatally shot.[27]

Notable people

- Pearl Alcock[28]

- Winifred Atwell opened "The Winifred Atwell Salon" at 82a Railton Road in 1956[29]

- Rotimi Fani-Kayode lived and died at 151 Railton Road[30]

- Darcus Howe[31]

- Leila Hassan, editor of Race Today[32]

- Linton Kwesi Johnson[31]

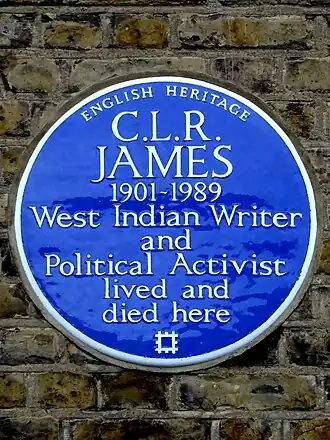

- C. L. R. James lived and died at 165 Railton Road, where in 2004 English Heritage erected a blue plaque.[33][34][35]

- Olive Morris and Liz Obi lived at 121 Railton Road[36]

Notable organisations

- 198 Contemporary Arts and Learning

- 121 Centre at 121 Railton Road

- The centre was home to a bookshop, a cafe, a meeting room, and offices for organisations such as The Anarchist Black Cross and the Faredodgers Association.

- It also hosted the legendary club night Dead by Dawn, and early sets by artists such as Hectate.[37]

- It was squatted as the 121 Centre from 1981 to 1999, making it one of London's longest continuous squats.[38] When it was evicted, Railton Road held a number of street parties mourning the loss of the important community asset.

- The building has now been converted into flats.

- Brixton Black Women's Group at 121 Railton Road[28]

- Black Panther Movement[28]

- South London Gay Community Centre, GLF and Brixton Fairies at number 78[39][40]

- The building has now been knocked down and converted into luxury apartments, with no reference to its past

- Race Today Collective at 165 Railton Road

Gallery

-

Blue Plaque at 165 Railton Road

Blue Plaque at 165 Railton Road -

198 Contemporary Arts and Learning, 198 Railton Road

198 Contemporary Arts and Learning, 198 Railton Road

See also

References

- ^ "232-234 Railton Road, The Herne Hill Society". Retrieved 15 August 2025.

- ^ "289 Railton Road, The Herne Hill Society". Retrieved 15 August 2025.

- ^ Urban, Mike (8 April 2017). "Brixton 15 Years Ago: Brockwell Park, Railton Road and drugs, April 2002". Retrieved 15 August 2025.

- ^ Hillard, Christopher (5 August 2025). "Housing and the Peripheralization of Race Politics in Britain, 1948–1977". Past & Present: 18.

- ^ a b Laura, Ana (2012). "A radical history of 121 Railton Road, Lambeth | libcom.org". libcom.org. Retrieved 14 August 2025.

- ^ a b Townson, Ian (2012). "The Brixton Fairies and the South London Gay Community Centre, Brixton 1974-6 -". Retrieved 14 August 2025.

- ^ "Stories from Railton Road". Brixton Advice Centre. 5 July 2015. Retrieved 14 August 2025.

- ^ "Pearl's a Zinger! – The Brixton Society". 27 October 2019. Retrieved 15 August 2025.

- ^ Adewole, Oluwatayo (2 February 2021). "Remembering Pearl Alcock, the Black bisexual shebeen queen of Brixton". gal-dem. Retrieved 6 June 2021.

- ^ Goodway, David (2008). "The Kate Sharpley Library". Anarchist Studies. 16 (1).

- ^ a b Meltzer, Albert (1996). I Couldn’t Paint Golden Angels, Ch 21. The Battle of Railton Road. The Anarchist Library.

- ^ J. A. Cloake & M. R. Tudor. Multicultural Britain. Oxford University Press, 2001. pp.60–64

- ^ "Brixton police cleared". Daily Mirror. 2 December 1981.

- ^ "Today in London anarchist history, 1999: the 121 Centre evicted, Brixton". LONDON RADICAL HISTORIES. 12 August 2019. Retrieved 15 August 2025.

- ^ "Today in London squatting history, 1984: the eviction of Effra Parade, Brixton". LONDON RADICAL HISTORIES. 25 March 2018. Retrieved 15 August 2025.

- ^ "Brixton, Riot Police Halt Mob". Daily Express. 2 November 1982.

- ^ "Today in London squatting history, 1984: the eviction of Effra Parade, Brixton". LONDON RADICAL HISTORIES. 25 March 2018. Retrieved 15 August 2025.

- ^ Davis, Lucy; Bayode, Folami (2005). "The 198 Gallery". In Atkinson, Dennis; Dash, Paul (eds.). Social and Critical Practice in Art Education. Trentham Books. pp. 81–90. ISBN 9781858563114.

- ^ "198 Contemporary Arts and Learning - Lambeth". 26 November 2021. Retrieved 16 August 2025.

- ^ "In/Visible Cities at 198 CAL - 19 November 2015". 198 Contemporary Arts and Learning. November 2015. Archived from the original on 11 October 2016. Retrieved 21 August 2016.

- ^ "Mechatronic Circus Schools Exhibition - 6 December 2000 to 16 June 2001". 198 Contemporary Arts and Learning. Retrieved 21 August 2016.

- ^ "PUKIJAM, Jennifer Allen aka Quilla Constance - 26 March 2015 to 8 May 2015". 198 Contemporary Arts and Learning. Archived from the original on 23 January 2017. Retrieved 21 August 2016.

- ^ "To Gypsyland, Delaine Le Bas - 21 June 2014 to 20 August 2014". 198 Contemporary Arts and Learning. Archived from the original on 11 October 2016. Retrieved 21 August 2016.

- ^ "Social Impact Report 2015" (PDF). 198 Contemporary Arts and Learning. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 October 2016. Retrieved 22 August 2016.

- ^ Urban, Mike (15 June 2022). "A retrospective of the work of Pearl Alcock at the 198 Contemporary Arts Centre, Brixton, 15th Jun – 14th Aug 2022". Retrieved 16 August 2025.

- ^ Adewole, Oluwatayo (2 February 2021). "Remembering Pearl Alcock, the Black bisexual shebeen queen of Brixton". gal-dem. Retrieved 6 June 2021.

- ^ "Man arrested over Deliveroo driver death in Brixton shooting where rapper also killed". Mirror.

- ^ a b c Ford, Tanisha C. (2015). "Violence at Desmond's Hip City: Gender and Soul Power In London". In Kelley, Robin D. G.; et al. (eds.). The Other Special Relationship: Race, Rights, and Riots in Britain and the United States. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 9781137392718.

- ^ Baker, Rob (2015). Beautiful Idiots and Brilliant Lunatics: A Sideways Look at Twentieth-Century London. Amberley Publishing. ISBN 9781445651200.

- ^ "The Herne Hill Society Newsletter" (PDF) (103, Summer 2008). Retrieved 14 August 2016.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ a b Kenan, Malik (2012). From Fatwa to Jihad: The Rushdie Affair and Its Legacy. Atlantic Books. ISBN 9780857899132.

- ^ "Stories from Railton Road". Brixton Advice Centre. 5 July 2015. Retrieved 7 June 2020.

- ^ "Darcus Howe – fighter for Black people’s rights", Brixton Blog, 2 April 2017.

- ^ "CLR James | Writer | Blue Plaques". English Heritage.

- ^ Leila Hassan, Robin Bunce and Paul Field, "Books | Here to Stay, Here to Fight: On the history, and legacy, of 'Race Today'", Ceasefire, 31 October 2019.

- ^ Fisher, Tracey (2012). What's Left of Blackness: Feminisms, Transracial Solidarities, and the Politics of Belonging in Britain. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 9780230339170.

- ^ "railton road... the frontline etc". urban75 forums. 19 February 2007. Retrieved 18 April 2019.

- ^ "The history of the 121 Centre, a squatted community anarchist centre on 124 Railton Road, Brixton, London SE24". www.urban75.org. Retrieved 18 April 2019.

- ^ Feather, Stuart (2016). Blowing the Lid: Gay Liberation, Sexual Revolution and Radical Queens. John Hunt Publishing. ISBN 9781785351440.

- ^ editor (14 February 2012). "The Brixton Fairies and the South London Gay Community Centre, Brixton 1974-6". urban75 blog. Retrieved 18 April 2019.

{{cite web}}:|last=has generic name (help)