Portal:Fatimid Caliphate

Portal maintenance status: (January 2019)

|

Introduction

The Fatimid Caliphate (/ˈfætɪmɪd/; Arabic: الخلافة الفاطمیّة, romanized: al-Khilāfa al-Fāṭimiyya), also known as the Fatimid Empire, was a caliphate extant from the tenth to the twelfth centuries CE under the rule of the Fatimids, an Isma'ili Shi'a dynasty. Spanning a large area of North Africa and West Asia, it ranged from the western Mediterranean in the west to the Red Sea in the east. The Fatimids traced their ancestry to the Islamic prophet Muhammad's daughter Fatima and her husband Ali, the first Shi'a imam. The Fatimids were acknowledged as the rightful imams by different Isma'ili communities as well as by denominations in many other Muslim lands and adjacent regions. Originating during the Abbasid Caliphate, the Fatimids initially conquered Ifriqiya (roughly present-day Tunisia and north-eastern Algeria). They extended their rule across the Mediterranean coast and ultimately made Egypt the center of the caliphate. At its height, the caliphate included—in addition to Egypt—varying areas of the Maghreb, Sicily, the Levant, and the Hejaz.

Between 902 and 909, the foundation of the Fatimid state was realized under the leadership of da'i (missionary) Abu Abdallah, whose conquest of Aghlabid Ifriqiya with the help of Kutama forces paved the way for the establishment of the Caliphate. After the conquest, Abdallah al-Mahdi Billah was retrieved from Sijilmasa and then accepted as the Imam of the movement, becoming the first Caliph and founder of the dynasty in 909. In 921, the city of al-Mahdiyya was established as the capital. In 948, they shifted their capital to al-Mansuriyya, near Kairouan. In 969, during the reign of al-Mu'izz, they conquered Egypt, and in 973, the caliphate was moved to the newly founded Fatimid capital of Cairo. Egypt became the political, cultural, and religious centre of the empire and it developed a new and "indigenous Arabic culture". After its initial conquests, the caliphate often allowed a degree of religious tolerance towards non-Shi'a sects of Islam, as well as to Jews and Christians. However, its leaders made little headway in persuading the Egyptian population to adopt its religious beliefs. (Full article...)

Selected articles

-

Image 1Ridwan ibn Walakhshi (Arabic: رضوان بن ولخشي) was the vizier of the Fatimid Caliphate in 1137–1139, under Caliph al-Hafiz li-Din Allah. He was a Sunni military commander, who rose to high offices under caliphs al-Amir bi-Ahkam Allah and al-Hafiz. He participated in the coup of Kutayfat, which in 1130–1131 briefly overthrew the Fatimid dynasty, serving as gaoler of the future caliph al-Hafiz. Under al-Hafiz he rose to the powerful position of chamberlain, and emerged as the leader of the Muslim opposition during the vizierate of the Christian Bahram al-Armani in 1135–1137, when he served as governor of Ascalon and the western Nile Delta.

Image 1Ridwan ibn Walakhshi (Arabic: رضوان بن ولخشي) was the vizier of the Fatimid Caliphate in 1137–1139, under Caliph al-Hafiz li-Din Allah. He was a Sunni military commander, who rose to high offices under caliphs al-Amir bi-Ahkam Allah and al-Hafiz. He participated in the coup of Kutayfat, which in 1130–1131 briefly overthrew the Fatimid dynasty, serving as gaoler of the future caliph al-Hafiz. Under al-Hafiz he rose to the powerful position of chamberlain, and emerged as the leader of the Muslim opposition during the vizierate of the Christian Bahram al-Armani in 1135–1137, when he served as governor of Ascalon and the western Nile Delta.

In February 1137, he rose in revolt against Bahram, drove him from Cairo, and was in turn appointed to the vizierate with the title of "Most Excellent King" (al-malik al-afdal) denoting his ambitions and status as a de facto monarch in his own right. His tenure lasted two years and five months, and was marked by a reorganization of the government and by a persecution of Christian officials, who were replaced by Muslims, as well as the introduction of restrictions on Christians and Jews. Ridwan also planned to depose al-Hafiz and the Fatimid dynasty in favour of a Sunni regime headed by himself, but the Caliph raised the army and the people of Cairo against him, forcing him to flee his post in June 1139. Ridwan rallied his followers and tried to capture Cairo, but was defeated and had to surrender. (Full article...) -

Image 2The siege of Ascalon took place from 25 January to 22 August 1153, in the time period between the Second and Third Crusades, and resulted in the capture of the Fatimid Egyptian fortress by the Kingdom of Jerusalem. Ascalon was an important castle that was used by the Fatimids to launch raids into the Crusader kingdom's territory, and by 1153 it was the last coastal city in Palestine that was not controlled by the Crusaders.

Image 2The siege of Ascalon took place from 25 January to 22 August 1153, in the time period between the Second and Third Crusades, and resulted in the capture of the Fatimid Egyptian fortress by the Kingdom of Jerusalem. Ascalon was an important castle that was used by the Fatimids to launch raids into the Crusader kingdom's territory, and by 1153 it was the last coastal city in Palestine that was not controlled by the Crusaders.

The siege lasted for several months without much progress, despite the usage of siege engines and catapults by the Crusader army. On 16 August, the Fatimids set fire to the siege tower, but the wind blew the flames back at the castle wall and caused part of it to collapse. A group of Knights Templar entered the breach, led by their grand master, Bernard de Tremelay. The other Crusaders did not follow them into the city and all forty Templars were killed. Three days later, a larger attack was launched by the Crusaders and the city surrendered after more fighting. Its inhabitants were given three days to leave Ascalon before the Crusaders formally took it over on 22 August 1153. (Full article...) -

Image 3Abū Manṣūr Ismāʿīl ibn al-Ḥāfiẓ (Arabic: أبو منصور إسماعيل بن الحافظ, February 1133 – April 1154), better known by his regnal name al-Ẓāfir bi-Amr Allāh (الظافر بأمر الله, lit. 'Victorious by the Command of God') or al-Ẓāfir bi-Aʿdāʾ Allāh (الظافر بأعداء الله, lit. 'Victor over God's Enemies'), was the twelfth Fatimid caliph, reigning in Egypt from 1149 to 1154, and the 22nd imam of the Hafizi Isma'ili branch of Shia Islam. (Full article...)

Image 3Abū Manṣūr Ismāʿīl ibn al-Ḥāfiẓ (Arabic: أبو منصور إسماعيل بن الحافظ, February 1133 – April 1154), better known by his regnal name al-Ẓāfir bi-Amr Allāh (الظافر بأمر الله, lit. 'Victorious by the Command of God') or al-Ẓāfir bi-Aʿdāʾ Allāh (الظافر بأعداء الله, lit. 'Victor over God's Enemies'), was the twelfth Fatimid caliph, reigning in Egypt from 1149 to 1154, and the 22nd imam of the Hafizi Isma'ili branch of Shia Islam. (Full article...) -

Image 4Sitt al-Mulk (Arabic: ست الملك, lit. 'Lady of the Kingdom'; 970–1023) was a Fatimid princess. After the disappearance of her half-brother, the caliph al-Hakim bi-Amr Allah, in 1021, she was instrumental in securing the succession of her nephew Ali az-Zahir, and acted as the de facto ruler of the state until her death on 5 February 1023. (Full article...)

Image 4Sitt al-Mulk (Arabic: ست الملك, lit. 'Lady of the Kingdom'; 970–1023) was a Fatimid princess. After the disappearance of her half-brother, the caliph al-Hakim bi-Amr Allah, in 1021, she was instrumental in securing the succession of her nephew Ali az-Zahir, and acted as the de facto ruler of the state until her death on 5 February 1023. (Full article...) -

Image 5Abu Tahir Isma'il (Arabic: أبو طاهر إسماعيل, romanized: Abū Ṭāhir ʾIsmāʿīl; January 914 – 18 March 953), better known by his regnal name al-Mansur Billah (Arabic: المنصور بالله, romanized: al-Manṣūr biʾllāh, lit. 'The Victor through God'), was the thirteenth Isma'ili imam and third caliph of the Fatimid Caliphate in Ifriqiya, ruling from 946 until his death. He succeeded his father, al-Qa'im, after the latter's death, in what was likely a bloodless palace coup. At the time of al-Mansur's accession, most of the Fatimid mainland realm in Ifriqiya had been lost to a large-scale anti-Fatimid revolt led by the Kharijite preacher Abu Yazid, who was laying siege to al-Qa'im's fortified coastal palace city of al-Mahdiya. Unlike his father he was an active and publicly visible monarch, but plagued by illness, which led to his early death.

Image 5Abu Tahir Isma'il (Arabic: أبو طاهر إسماعيل, romanized: Abū Ṭāhir ʾIsmāʿīl; January 914 – 18 March 953), better known by his regnal name al-Mansur Billah (Arabic: المنصور بالله, romanized: al-Manṣūr biʾllāh, lit. 'The Victor through God'), was the thirteenth Isma'ili imam and third caliph of the Fatimid Caliphate in Ifriqiya, ruling from 946 until his death. He succeeded his father, al-Qa'im, after the latter's death, in what was likely a bloodless palace coup. At the time of al-Mansur's accession, most of the Fatimid mainland realm in Ifriqiya had been lost to a large-scale anti-Fatimid revolt led by the Kharijite preacher Abu Yazid, who was laying siege to al-Qa'im's fortified coastal palace city of al-Mahdiya. Unlike his father he was an active and publicly visible monarch, but plagued by illness, which led to his early death.

Al-Mansur immediately took up the fight against the revolt with considerable energy, but kept his father's death secret until after the final suppression of the rebellion, governing instead as the ostensible designated successor and "Sword of the Imam". Leaving the trusted eunuch chamberlain Jawdhar to run the government in his stead, al-Mansur took to the field in person, leading the Fatimid army to victory over the rebel army outside Kairouan, and pursuing its remnants into the Hodna Mountains. After a long pursuit, Abu Yazid was finally cornered and captured, before dying of his injuries on 19 August 947. After Abu Yazid's death, al-Mansur publicly proclaimed his caliphate. His victory over Abu Yazid was celebrated as a triumph over a 'False Messiah', and as heralding a new beginning for the dynasty and its divine mission. Al-Mansur spent the remainder of his reign in al-Mansuriya, a new capital city he founded in 948. During his reign, he also secured the allegiance of the Sanhaja Berbers under Ziri ibn Manad, recaptured Tahert from the rebellious Miknasa Berbers, suppressed a revolt in the overseas Fatimid province of Sicily, launched naval raids against Byzantine holdings in southern Italy, and engaged in a mounting antagonism with the rival Umayyad state of Córdoba. (Full article...) -

Image 6The siege of Aleppo was a siege of the Hamdanid capital Aleppo by the army of the Fatimid Caliphate under Manjutakin from the spring of 994 to April 995. Manjutakin laid siege to the city over the winter, while the population of Aleppo starved and suffered from disease. In the spring of 995, the emir of Aleppo appealed for help from Byzantine emperor Basil II. The arrival of a Byzantine relief army under the emperor in April 995 compelled the Fatimid forces to give up the siege and retreat south. (Full article...)

Image 6The siege of Aleppo was a siege of the Hamdanid capital Aleppo by the army of the Fatimid Caliphate under Manjutakin from the spring of 994 to April 995. Manjutakin laid siege to the city over the winter, while the population of Aleppo starved and suffered from disease. In the spring of 995, the emir of Aleppo appealed for help from Byzantine emperor Basil II. The arrival of a Byzantine relief army under the emperor in April 995 compelled the Fatimid forces to give up the siege and retreat south. (Full article...) -

Image 7The first Fatimid invasion of Egypt occurred in 914–915, soon after the establishment of the Fatimid Caliphate in Ifriqiya in 909. The Fatimids launched an expedition east, against the Abbasid Caliphate, under the Berber General Habasa ibn Yusuf. Habasa succeeded in subduing the cities on the Libyan coast between Ifriqiya and Egypt, and captured Alexandria. The Fatimid heir-apparent, al-Qa'im bi-Amr Allah, then arrived to take over the campaign. Attempts to conquer the Egyptian capital, Fustat, were beaten back by the Abbasid troops in the province. A risky affair even at the outset, the arrival of Abbasid reinforcements from Syria and Iraq under Mu'nis al-Muzaffar doomed the invasion to failure, and al-Qa'im and the remnants of his army abandoned Alexandria and returned to Ifriqiya in May 915. The failure did not prevent the Fatimids from launching another unsuccessful attempt to capture Egypt four years later. It was not until 969 that the Fatimids conquered Egypt and made it the centre of their empire. (Full article...)

Image 7The first Fatimid invasion of Egypt occurred in 914–915, soon after the establishment of the Fatimid Caliphate in Ifriqiya in 909. The Fatimids launched an expedition east, against the Abbasid Caliphate, under the Berber General Habasa ibn Yusuf. Habasa succeeded in subduing the cities on the Libyan coast between Ifriqiya and Egypt, and captured Alexandria. The Fatimid heir-apparent, al-Qa'im bi-Amr Allah, then arrived to take over the campaign. Attempts to conquer the Egyptian capital, Fustat, were beaten back by the Abbasid troops in the province. A risky affair even at the outset, the arrival of Abbasid reinforcements from Syria and Iraq under Mu'nis al-Muzaffar doomed the invasion to failure, and al-Qa'im and the remnants of his army abandoned Alexandria and returned to Ifriqiya in May 915. The failure did not prevent the Fatimids from launching another unsuccessful attempt to capture Egypt four years later. It was not until 969 that the Fatimids conquered Egypt and made it the centre of their empire. (Full article...) -

Image 8The Battle of the Blacks or Battle of the Slaves was a conflict in Cairo that occurred during the Rise of Saladin in Egypt, on 21–23 August 1169, between the black African units of the Fatimid army and other pro-Fatimid elements, and Sunni Syrian troops loyal to the Fatimid vizier, Saladin. Saladin's rise to the vizierate, and his sidelining of the Fatimid caliph, al-Adid, antagonized the traditional Fatimid elites, including the army regiments, as Saladin relied chiefly on the Kurdish and Turkish cavalry that had come with him from Syria. According to the medieval sources, which are biased towards Saladin, this conflict led to an attempt by the palace majordomo, Mu'tamin al-Khilafa, to enter into an agreement with the Crusaders and jointly attack Saladin's forces to get rid of him. Saladin learned of this conspiracy and had Mu'tamin executed on 20 August. Modern historians have questioned the veracity of this report, suspecting that it may have been invented to justify Saladin's subsequent move against the Fatimid troops.

Image 8The Battle of the Blacks or Battle of the Slaves was a conflict in Cairo that occurred during the Rise of Saladin in Egypt, on 21–23 August 1169, between the black African units of the Fatimid army and other pro-Fatimid elements, and Sunni Syrian troops loyal to the Fatimid vizier, Saladin. Saladin's rise to the vizierate, and his sidelining of the Fatimid caliph, al-Adid, antagonized the traditional Fatimid elites, including the army regiments, as Saladin relied chiefly on the Kurdish and Turkish cavalry that had come with him from Syria. According to the medieval sources, which are biased towards Saladin, this conflict led to an attempt by the palace majordomo, Mu'tamin al-Khilafa, to enter into an agreement with the Crusaders and jointly attack Saladin's forces to get rid of him. Saladin learned of this conspiracy and had Mu'tamin executed on 20 August. Modern historians have questioned the veracity of this report, suspecting that it may have been invented to justify Saladin's subsequent move against the Fatimid troops.

This event provoked the uprising of the black African troops of the Fatimid army, numbering some 50,000 men, who were joined by Armenian soldiers and the populace of Cairo the next day. The clashes lasted for two days, as the Fatimid troops initially attacked the vizier's palace, but were driven back to the large square between the Fatimid Great Palaces. There the black African troops and their allies appeared to be gaining the upper hand until al-Adid came out publicly against them, and Saladin ordered the burning of their settlements, located south of Cairo outside the city wall, where the black Africans' families had been left behind. The black Africans then broke and retreated in disorder to the south, until they were encircled near the Bab Zuwayla gate, where they surrendered and were allowed to cross the Nile to Giza. Despite promises of safety, they were attacked and almost annihilated there by Saladin's brother Turan-Shah. (Full article...) -

Image 9The navy of the Fatimid Caliphate was one of the most developed early Muslim navies and a major force in the central and eastern Mediterranean in the 10th–12th centuries. As with the dynasty it served, its history is in two phases. The first was c. 909 to 969, when the Fatimids were based in Ifriqiya (modern Tunisia); the second lasted until the end of the dynasty in 1171, when they were based in Egypt. During the first period, the navy was employed mainly against the Byzantine Empire in Sicily and southern Italy, where it enjoyed mixed success. It was also in the initially unsuccessful attempts to conquer Egypt from the Abbasids and brief clashes with the Umayyad Caliphate of Córdoba.

Image 9The navy of the Fatimid Caliphate was one of the most developed early Muslim navies and a major force in the central and eastern Mediterranean in the 10th–12th centuries. As with the dynasty it served, its history is in two phases. The first was c. 909 to 969, when the Fatimids were based in Ifriqiya (modern Tunisia); the second lasted until the end of the dynasty in 1171, when they were based in Egypt. During the first period, the navy was employed mainly against the Byzantine Empire in Sicily and southern Italy, where it enjoyed mixed success. It was also in the initially unsuccessful attempts to conquer Egypt from the Abbasids and brief clashes with the Umayyad Caliphate of Córdoba.

During the first decades after the eventual Fatimid conquest of Egypt in 969, the main naval enemy remained the Byzantines, but the war was fought mostly on land over control of Syria, and naval operations were limited to maintaining Fatimid control over the coastal cities of the Levant. Warfare with the Byzantines ended after 1000 with a series of truces, and the navy became once more important with the arrival of the Crusaders in the Holy Land in the late 1090s. (Full article...) -

Image 10The First Crusade (1096–1099) was the first of a series of religious wars, or Crusades, which were initiated, supported and at times directed by the Latin Church in the Middle Ages. Their aim was to return the Holy Land—which had been conquered by the Rashidun Caliphate in the 7th century—to Christian rule. By the 11th century, although Jerusalem had then been ruled by Muslims for hundreds of years, the practices of the Seljuk rulers in the region began to threaten local Christian populations, pilgrimages from the West and the Byzantine Empire itself. The earliest impetus for the First Crusade came in 1095 when Byzantine emperor Alexios I Komnenos sent ambassadors to the Council of Piacenza to request military support in the empire's conflict with the Seljuk-led Turks. This was followed later in the year by the Council of Clermont, at which Pope Urban II gave a speech supporting the Byzantine request and urging faithful Christians to undertake an armed pilgrimage to Jerusalem.

Image 10The First Crusade (1096–1099) was the first of a series of religious wars, or Crusades, which were initiated, supported and at times directed by the Latin Church in the Middle Ages. Their aim was to return the Holy Land—which had been conquered by the Rashidun Caliphate in the 7th century—to Christian rule. By the 11th century, although Jerusalem had then been ruled by Muslims for hundreds of years, the practices of the Seljuk rulers in the region began to threaten local Christian populations, pilgrimages from the West and the Byzantine Empire itself. The earliest impetus for the First Crusade came in 1095 when Byzantine emperor Alexios I Komnenos sent ambassadors to the Council of Piacenza to request military support in the empire's conflict with the Seljuk-led Turks. This was followed later in the year by the Council of Clermont, at which Pope Urban II gave a speech supporting the Byzantine request and urging faithful Christians to undertake an armed pilgrimage to Jerusalem.

This call was met with an enthusiastic popular response across all social classes in western Europe. Thousands of predominantly poor Christians, led by the French priest Peter the Hermit, were the first to respond. What has become known as the People's Crusade passed through Germany and indulged in wide-ranging anti-Jewish activities, including the Rhineland massacres. On leaving Byzantine-controlled territory in Anatolia, they were annihilated in a Turkish ambush led by the Seljuk Kilij Arslan I at the Battle of Civetot in October 1096. (Full article...) -

Image 11The Order of Assassins (Arabic: حَشّاشِین, romanized: Ḥashshāshīyīn; Persian: حشاشين, romanized: Ḥaššāšīn) were a Nizari Isma'ili order that existed between 1090 and 1275 AD, founded by Hasan al-Sabbah.

Image 11The Order of Assassins (Arabic: حَشّاشِین, romanized: Ḥashshāshīyīn; Persian: حشاشين, romanized: Ḥaššāšīn) were a Nizari Isma'ili order that existed between 1090 and 1275 AD, founded by Hasan al-Sabbah.

During that time, they lived in the mountain castles in Persia and the Levant, and held a strict subterfuge policy throughout the Middle East, posing a substantial strategic threat to Fatimid, Abbasid, and Seljuk authority, and killing several Christian leaders. Over the course of nearly 200 years, they killed hundreds who were considered leading enemies of the Nizari Isma'ili state. The modern term assassination is believed to stem from the tactics used by the Assassins. (Full article...) -

Image 12Abd al-Rahim ibn Ilyas ibn Ahmad ibn al-Mahdi (Arabic: عبد الرحيم ابن إلياس ابن احمد بن المهدي) was a member of the Fatimid dynasty who was named heir-apparent by the caliph al-Hakim bi-Amr Allah in 1013. When al-Hakim was murdered in 1021, he was sidelined in favour of al-Hakim's son, Ali al-Zahir, arrested and imprisoned. He died in captivity, officially by his own hands, or assassinated by the real power behind al-Zahir's throne, the princess Sitt al-Mulk. (Full article...)

Image 12Abd al-Rahim ibn Ilyas ibn Ahmad ibn al-Mahdi (Arabic: عبد الرحيم ابن إلياس ابن احمد بن المهدي) was a member of the Fatimid dynasty who was named heir-apparent by the caliph al-Hakim bi-Amr Allah in 1013. When al-Hakim was murdered in 1021, he was sidelined in favour of al-Hakim's son, Ali al-Zahir, arrested and imprisoned. He died in captivity, officially by his own hands, or assassinated by the real power behind al-Zahir's throne, the princess Sitt al-Mulk. (Full article...) -

Image 13The Kutama (Berber: Ikutamen; Arabic: كتامة) were a Berber tribe in northern Algeria classified among the Berber confederation of the Bavares. The Kutama are attested much earlier, in the form Koidamousii by the Greek geographer Ptolemy.

Image 13The Kutama (Berber: Ikutamen; Arabic: كتامة) were a Berber tribe in northern Algeria classified among the Berber confederation of the Bavares. The Kutama are attested much earlier, in the form Koidamousii by the Greek geographer Ptolemy.

The Kutama played a pivotal role in establishing the Fatimid Caliphate (909–1171), forming the bulk of the Fatimid army which eventually overthrew the Aghlabids who controlled Ifriqiya, and which then went on to conquer Egypt, Sudan, Hijaz and the southern Levant in 969–975. The Kutama remained one of the mainstays of the Fatimid army until well into the 11th century. (Full article...) -

![Image 14 Cairo (/ˈkaɪroʊ/ ⓘ KY-roh; Arabic: القاهرة, romanized: al-Qāhirah, Egyptian Arabic: [el‿ˈqɑːheɾɑ] ⓘ) is the capital and largest city of Egypt and the Cairo Governorate, being home to more than 10 million people. It is also part of the largest urban agglomeration in Africa, the Arab world, and the Middle East. The Greater Cairo metropolitan area is one of the largest in the world by population with over 22.2 million people. The area that would become Cairo was part of ancient Egypt, as the Giza pyramid complex and the ancient cities of Memphis and Heliopolis are near-by. Located near the Nile Delta, the predecessor settlement was Fustat following the Muslim conquest of Egypt in 641 next to an existing ancient Roman fortress, Babylon. Subsequently, Cairo was founded by the Fatimid dynasty in 969. It later superseded Fustat as the main urban centre during the Ayyubid and Mamluk periods (12th–16th centuries). (Full article...)](./_assets_/Blank.png) Image 14Cairo (/ˈkaɪroʊ/ ⓘ KY-roh; Arabic: القاهرة, romanized: al-Qāhirah, Egyptian Arabic: [el‿ˈqɑːheɾɑ] ⓘ) is the capital and largest city of Egypt and the Cairo Governorate, being home to more than 10 million people. It is also part of the largest urban agglomeration in Africa, the Arab world, and the Middle East. The Greater Cairo metropolitan area is one of the largest in the world by population with over 22.2 million people.

Image 14Cairo (/ˈkaɪroʊ/ ⓘ KY-roh; Arabic: القاهرة, romanized: al-Qāhirah, Egyptian Arabic: [el‿ˈqɑːheɾɑ] ⓘ) is the capital and largest city of Egypt and the Cairo Governorate, being home to more than 10 million people. It is also part of the largest urban agglomeration in Africa, the Arab world, and the Middle East. The Greater Cairo metropolitan area is one of the largest in the world by population with over 22.2 million people.

The area that would become Cairo was part of ancient Egypt, as the Giza pyramid complex and the ancient cities of Memphis and Heliopolis are near-by. Located near the Nile Delta, the predecessor settlement was Fustat following the Muslim conquest of Egypt in 641 next to an existing ancient Roman fortress, Babylon. Subsequently, Cairo was founded by the Fatimid dynasty in 969. It later superseded Fustat as the main urban centre during the Ayyubid and Mamluk periods (12th–16th centuries). (Full article...) -

Image 15Abū al-Qāsim Aḥmad ibn al-Mustanṣir (Arabic: أبو القاسم أحمد بن المستنصر; 15/16 September 1074 – 11/12 December 1101), better known by his regnal name al-Mustaʿlī biʾllāh (المستعلي بالله, lit. 'The One Raised Up by God'), was the ninth Fatimid caliph and the 19th imam of Musta'li Ismailism.

Image 15Abū al-Qāsim Aḥmad ibn al-Mustanṣir (Arabic: أبو القاسم أحمد بن المستنصر; 15/16 September 1074 – 11/12 December 1101), better known by his regnal name al-Mustaʿlī biʾllāh (المستعلي بالله, lit. 'The One Raised Up by God'), was the ninth Fatimid caliph and the 19th imam of Musta'li Ismailism.

Although not the eldest (and most likely the youngest) of the sons of Caliph al-Mustansir Billah, al-Musta'li became caliph through the machinations of his brother-in-law, the vizier al-Afdal Shahanshah. In response, his oldest brother and most likely candidate for their father's succession, Nizar, rose in revolt in Alexandria but was defeated and executed. This caused a major split in the Isma'ili movement. Many communities, especially in Persia and Iraq, split off from the officially sponsored Isma'ili hierarchy and formed their own Nizari movement, holding Nizar and his descendants as the rightful imams. (Full article...) -

Image 16Abū Ḥanīfa al-Nuʿmān ibn Muḥammad ibn Manṣūr ibn Aḥmad ibn Ḥayyūn al-Tamīmiyy (Arabic: النعمان بن محمد بن منصور بن أحمد بن حيون التميمي, generally known as al-Qāḍī al-Nu‘mān (القاضي النعمان) or as ibn Ḥayyūn (ابن حيون) (died 974 CE/363 AH) was an Isma'ili jurist and the official historian of the Fatimid Caliphate. He was also called Qāḍī al-Quḍāt (قَاضِي القضاة) "Jurist of the Jurists" and Dāʻī al-Duʻāt (داعي الدعاة) "Missionary of Missionaries". (Full article...)

Image 16Abū Ḥanīfa al-Nuʿmān ibn Muḥammad ibn Manṣūr ibn Aḥmad ibn Ḥayyūn al-Tamīmiyy (Arabic: النعمان بن محمد بن منصور بن أحمد بن حيون التميمي, generally known as al-Qāḍī al-Nu‘mān (القاضي النعمان) or as ibn Ḥayyūn (ابن حيون) (died 974 CE/363 AH) was an Isma'ili jurist and the official historian of the Fatimid Caliphate. He was also called Qāḍī al-Quḍāt (قَاضِي القضاة) "Jurist of the Jurists" and Dāʻī al-Duʻāt (داعي الدعاة) "Missionary of Missionaries". (Full article...) -

Image 17The Druze, who call themselves al-Muwaḥḥidūn (lit. 'the monotheists' or 'the unitarians'), are an Arab esoteric religious group from West Asia who adhere to the Druze faith, an Abrahamic, monotheistic, and syncretic religion whose main tenets assert the unity of God, reincarnation, and the eternity of the soul.

Image 17The Druze, who call themselves al-Muwaḥḥidūn (lit. 'the monotheists' or 'the unitarians'), are an Arab esoteric religious group from West Asia who adhere to the Druze faith, an Abrahamic, monotheistic, and syncretic religion whose main tenets assert the unity of God, reincarnation, and the eternity of the soul.

Although the Druze faith developed from Isma'ilism, Druze do not identify as Muslims. They maintain the Arabic language and culture as integral parts of their identity, with Arabic being their primary language. Most Druze religious practices are kept secret, and conversion to their religion is not permitted for outsiders. Interfaith marriages are rare and strongly discouraged. They differentiate between spiritual individuals, known as "uqqāl", who hold the faith's secrets, and secular ones, known as "juhhāl", who focus on worldly matters. Druze believe that, after completing the cycle of rebirth through successive reincarnations, the soul reunites with the Cosmic Mind (al-ʻaql al-kullī). (Full article...) -

Image 18Musta'li Isma'ilism (Arabic: المستعلية, romanized: al-Mustaʿliyya) is a branch of Isma'ilism named for their acceptance of al-Musta'li as the legitimate ninth Fatimid caliph and legitimate successor to his father, al-Mustansir Billah (r. 1036–1094/1095). The Nizari the other living branch of Ismailism, led by Aga Khan V believe the ninth caliph was al-Musta'li's elder brother, Nizar.

Image 18Musta'li Isma'ilism (Arabic: المستعلية, romanized: al-Mustaʿliyya) is a branch of Isma'ilism named for their acceptance of al-Musta'li as the legitimate ninth Fatimid caliph and legitimate successor to his father, al-Mustansir Billah (r. 1036–1094/1095). The Nizari the other living branch of Ismailism, led by Aga Khan V believe the ninth caliph was al-Musta'li's elder brother, Nizar.

The Musta'li originated in Fatimid-ruled Egypt, later moved its religious center to Yemen, and gained a foothold in 11th-century Western India through missionaries. (Full article...) -

![Image 19 Abu Ali Salih ibn Mirdas also known by his laqab (honorific epithet) Asad al-Dawla (lit. 'Lion of the State'), was the founder of the Mirdasid dynasty and emir of Aleppo from 1025 until his death in May 1029. At its peak, his emirate (principality) encompassed much of the western Jazira (Upper Mesopotamia), northern Syria and several central Syrian towns. With occasional interruption, Salih's descendants ruled Aleppo for the next five decades. Salih launched his career in 1008, when he seized the Euphrates river fortress of al-Rahba. In 1012, he was imprisoned and tortured by the emir of Aleppo, Mansur ibn Lu'lu'. Two years later he escaped, capturing Mansur in battle and releasing him for numerous concessions, including half of Aleppo's revenues. This cemented Salih as the paramount emir of his tribe, the Banu Kilab, many of whose chieftains had died in Mansur's dungeons. With his Bedouin warriors, Salih captured a string of fortresses along the Euphrates, including Manbij and Raqqa, by 1022. He later formed an alliance with the Banu Kalb and Banu Tayy tribes and supported their struggle against the Fatimids of Egypt. During this tribal rebellion, Salih annexed the central Syrian towns of Homs, Baalbek and Sidon, before conquering Fatimid-held Aleppo in 1025, bringing "to success the plan which guided his [Banu Kilab] forebears for a century", according to historian Thierry Bianquis. (Full article...)](./_assets_/Blank.png) Image 19Abu Ali Salih ibn Mirdas also known by his laqab (honorific epithet) Asad al-Dawla (lit. 'Lion of the State'), was the founder of the Mirdasid dynasty and emir of Aleppo from 1025 until his death in May 1029. At its peak, his emirate (principality) encompassed much of the western Jazira (Upper Mesopotamia), northern Syria and several central Syrian towns. With occasional interruption, Salih's descendants ruled Aleppo for the next five decades.

Image 19Abu Ali Salih ibn Mirdas also known by his laqab (honorific epithet) Asad al-Dawla (lit. 'Lion of the State'), was the founder of the Mirdasid dynasty and emir of Aleppo from 1025 until his death in May 1029. At its peak, his emirate (principality) encompassed much of the western Jazira (Upper Mesopotamia), northern Syria and several central Syrian towns. With occasional interruption, Salih's descendants ruled Aleppo for the next five decades.

Salih launched his career in 1008, when he seized the Euphrates river fortress of al-Rahba. In 1012, he was imprisoned and tortured by the emir of Aleppo, Mansur ibn Lu'lu'. Two years later he escaped, capturing Mansur in battle and releasing him for numerous concessions, including half of Aleppo's revenues. This cemented Salih as the paramount emir of his tribe, the Banu Kilab, many of whose chieftains had died in Mansur's dungeons. With his Bedouin warriors, Salih captured a string of fortresses along the Euphrates, including Manbij and Raqqa, by 1022. He later formed an alliance with the Banu Kalb and Banu Tayy tribes and supported their struggle against the Fatimids of Egypt. During this tribal rebellion, Salih annexed the central Syrian towns of Homs, Baalbek and Sidon, before conquering Fatimid-held Aleppo in 1025, bringing "to success the plan which guided his [Banu Kilab] forebears for a century", according to historian Thierry Bianquis. (Full article...) -

Image 20Shawar ibn Mujir al-Sa'di (Arabic: شاور بن مجير السعدي, romanized: Shāwar ibn Mujīr al-Saʿdī; died 18 January 1169) was the de facto ruler of Fatimid Egypt, as its vizier, from December 1162 until his assassination in 1169 by the general Shirkuh, the uncle of the future Ayyubid leader Saladin, with whom he was engaged in a three-way power struggle against the Crusader Amalric I of Jerusalem. Shawar was notorious for continually switching alliances, allying first with one side, and then the other, and even ordering the burning of his own capital city, Fustat, just so that the enemy could not have it. (Full article...)

Image 20Shawar ibn Mujir al-Sa'di (Arabic: شاور بن مجير السعدي, romanized: Shāwar ibn Mujīr al-Saʿdī; died 18 January 1169) was the de facto ruler of Fatimid Egypt, as its vizier, from December 1162 until his assassination in 1169 by the general Shirkuh, the uncle of the future Ayyubid leader Saladin, with whom he was engaged in a three-way power struggle against the Crusader Amalric I of Jerusalem. Shawar was notorious for continually switching alliances, allying first with one side, and then the other, and even ordering the burning of his own capital city, Fustat, just so that the enemy could not have it. (Full article...) -

Image 21Al-Qaid Jawhar ibn Abdallah (Arabic: جوهر بن عبد الله, romanized: Jawhar ibn ʿAbd Allāh, better known as Jawhar al Siqilli, al-Qaid al-Siqilli, "The Sicilian General", or al-Saqlabi, "The Slav"; born in the Byzantine Empire and died 28 April 992) was a Sunni Fatimid general who led the conquest of Maghreb, and subsequently the conquest of Egypt, for the 4th Fatimid Imam-Caliph al-Mu'izz li-Din Allah. He served as viceroy of Egypt until al-Mu'izz's arrival in 973, consolidating Fatimid control over the country and laying the foundations for the city of Cairo. After that, he retired from public life until his death.

Image 21Al-Qaid Jawhar ibn Abdallah (Arabic: جوهر بن عبد الله, romanized: Jawhar ibn ʿAbd Allāh, better known as Jawhar al Siqilli, al-Qaid al-Siqilli, "The Sicilian General", or al-Saqlabi, "The Slav"; born in the Byzantine Empire and died 28 April 992) was a Sunni Fatimid general who led the conquest of Maghreb, and subsequently the conquest of Egypt, for the 4th Fatimid Imam-Caliph al-Mu'izz li-Din Allah. He served as viceroy of Egypt until al-Mu'izz's arrival in 973, consolidating Fatimid control over the country and laying the foundations for the city of Cairo. After that, he retired from public life until his death.

He is variously known with the nisbas al-Siqilli (Arabic: الصقلي, romanized: al-Ṣiqillī, lit. 'The Sicilian'), al-Saqlabi (Arabic: الصقلبي, lit. The Slav), al-Rumi (Arabic: الرومي, romanized: al-Rūmī, lit. 'the Roman'); and with the titles al-Katib (Arabic: الكَاتِب, romanized: al-Kātib, lit. 'the Secretary') and al-Qa'id (Arabic: القائد, romanized: al-Qāʾid, lit. 'the General'). (Full article...) -

Image 22The House of Knowledge (Arabic: دار العلم, romanized: Dār al-ʿIlm) was a medieval university built by the Fatimid Caliphate in Cairo in 1004 CE. Originally a library, the House of Knowledge was converted to a state university by the Fatimid Imam-Caliph al-Hakim bi-Amr Allah in the same year.

Image 22The House of Knowledge (Arabic: دار العلم, romanized: Dār al-ʿIlm) was a medieval university built by the Fatimid Caliphate in Cairo in 1004 CE. Originally a library, the House of Knowledge was converted to a state university by the Fatimid Imam-Caliph al-Hakim bi-Amr Allah in the same year.

In keeping with the Islamic tradition of knowledge, the Fatimids collected books on a variety of subjects and their libraries attracted the attention of scholars from around the world. al-Hakim was a great patron of learning and provided paper, pens, ink and inkstands without charge to all those who wished to study there. (Full article...) -

Image 23The Sulayhid dynasty (Arabic: بَنُو صُلَيْح, romanized: Banū Ṣulayḥ, lit. 'Children of Sulayh') was an Ismaili Shi'ite Arab dynasty established in 1047 by Ali ibn Muhammad al-Sulayhi that ruled most of historical Yemen at its peak. The Sulayhids brought to Yemen peace and a prosperity unknown since Himyaritic times. The regime was confederate with the Cairo-based Fatimid Caliphate, and was a constant enemy of the Rassids - the Zaidi Shi'ite rulers of Yemen throughout its existence. The dynasty ended with Arwa al-Sulayhi affiliating to the Taiyabi Ismaili sect, as opposed to the Hafizi Ismaili sect that the other Ismaili dynasties such as the Zurayids and the Hamdanids adhered to. (Full article...)

Image 23The Sulayhid dynasty (Arabic: بَنُو صُلَيْح, romanized: Banū Ṣulayḥ, lit. 'Children of Sulayh') was an Ismaili Shi'ite Arab dynasty established in 1047 by Ali ibn Muhammad al-Sulayhi that ruled most of historical Yemen at its peak. The Sulayhids brought to Yemen peace and a prosperity unknown since Himyaritic times. The regime was confederate with the Cairo-based Fatimid Caliphate, and was a constant enemy of the Rassids - the Zaidi Shi'ite rulers of Yemen throughout its existence. The dynasty ended with Arwa al-Sulayhi affiliating to the Taiyabi Ismaili sect, as opposed to the Hafizi Ismaili sect that the other Ismaili dynasties such as the Zurayids and the Hamdanids adhered to. (Full article...) -

Image 24The Battle of Apamea was fought on 19 July 998 between the forces of the Byzantine Empire and the Fatimid Caliphate. The battle was part of a series of military confrontations between the two powers over control of northern Syria and the Hamdanid emirate of Aleppo, which in turn were part of the larger series of regional conflicts known as the Arab–Byzantine wars. The Byzantine regional commander, Damian Dalassenos, had been besieging Apamea, until the arrival of the Fatimid relief army from Damascus, under Jaysh ibn Samsama. In the subsequent battle, the Byzantines were initially victorious, but a lone Kurdish rider managed to kill Dalassenos, throwing the Byzantine army into panic. The fleeing Byzantines were then pursued, with much loss of life, by the Fatimid troops. This defeat forced the Byzantine emperor Basil II to personally campaign in the region the next year, and was followed in 1001 by the conclusion of a ten-year truce between the two states.

Image 24The Battle of Apamea was fought on 19 July 998 between the forces of the Byzantine Empire and the Fatimid Caliphate. The battle was part of a series of military confrontations between the two powers over control of northern Syria and the Hamdanid emirate of Aleppo, which in turn were part of the larger series of regional conflicts known as the Arab–Byzantine wars. The Byzantine regional commander, Damian Dalassenos, had been besieging Apamea, until the arrival of the Fatimid relief army from Damascus, under Jaysh ibn Samsama. In the subsequent battle, the Byzantines were initially victorious, but a lone Kurdish rider managed to kill Dalassenos, throwing the Byzantine army into panic. The fleeing Byzantines were then pursued, with much loss of life, by the Fatimid troops. This defeat forced the Byzantine emperor Basil II to personally campaign in the region the next year, and was followed in 1001 by the conclusion of a ten-year truce between the two states.

The Arab–Byzantine wars were a series of wars between a number of Muslim-Arab dynasties and the Byzantine Empire from the 7th to the 11th century. Conflict started during the initial Muslim conquests, under the expansionist Rashidun and Umayyad caliphs, in the 7th century and continued by their successors until the mid-11th century. (Full article...) -

Image 25Abū Tamīm Maʿad al-Mustanṣir biʾllāh (Arabic: أبو تميم معد المستنصر بالله; 2 July 1029 – 29 December 1094) was the eighth Fatimid Caliph from 1036 until 1094. He was one of the longest reigning Muslim rulers. His reign was the twilight of the Fatimid state. The start of his reign saw the continuation of competent administrators running the Fatimid state (Anushtakin, al-Jarjara'i, and later al-Yazuri), overseeing the state's prosperity in the first two decades of al-Mustansir's reign. However, the break out of court infighting between the Turkish and Berber/Sudanese court factions following al-Yazuri's assassination, coinciding with natural disasters in Egypt and the gradual loss of administrative control over Fatimid possessions outside of Egypt, almost resulted in the total collapse of the Fatimid state in the 1060s, before the appointment of the Armenian general Badr al-Jamali, who assumed power as vizier in 1073, and became the de facto dictator of the country under the nominal rule of al-Mustansir.

Image 25Abū Tamīm Maʿad al-Mustanṣir biʾllāh (Arabic: أبو تميم معد المستنصر بالله; 2 July 1029 – 29 December 1094) was the eighth Fatimid Caliph from 1036 until 1094. He was one of the longest reigning Muslim rulers. His reign was the twilight of the Fatimid state. The start of his reign saw the continuation of competent administrators running the Fatimid state (Anushtakin, al-Jarjara'i, and later al-Yazuri), overseeing the state's prosperity in the first two decades of al-Mustansir's reign. However, the break out of court infighting between the Turkish and Berber/Sudanese court factions following al-Yazuri's assassination, coinciding with natural disasters in Egypt and the gradual loss of administrative control over Fatimid possessions outside of Egypt, almost resulted in the total collapse of the Fatimid state in the 1060s, before the appointment of the Armenian general Badr al-Jamali, who assumed power as vizier in 1073, and became the de facto dictator of the country under the nominal rule of al-Mustansir.

The caliph al-Mustanṣir bi-llāh was the last Imam before a disastrous split divided the Isma'ili movement in two, due to the struggle in the succession between al-Mustansir's older son, Nizar, and the younger al-Mustaʽli, who was raised to the throne by Badr's son and successor, al-Afdal Shahanshah. The followers of Nizar, who predominated in Iran and Syria, became the Nizari branch of Isma'ilism, while those of al-Musta'li became the Musta'li branch. (Full article...)

Did you know...

- ... that medieval Muslim historians blamed al-Amir bi-Ahkam Allah for the loss of much of Palestine to the crusaders but, in reality, he played no role in the Fatimid government during that period?

- ... that Da'ud, the heir apparent of the last Fatimid caliph, spent almost his entire life imprisoned by the succeeding Ayyubid dynasty?

- ... that Abbas ibn Abi al-Futuh was a Zirid prince who became a vizier of the Fatimid Caliphate after assassinating his stepfather, and was overthrown after murdering caliph al-Zafir?

- ... that Abd al-Rahim ibn Ilyas, heir apparent of the Fatimid Caliphate, was arrested after the caliph's death and died in captivity under unclear circumstances?

Need help?

Do you have a question about the Fatimid Caliphate that you can't find the answer to?

Consider asking it at the Wikipedia reference desk or at the talk page of WikiProject Islam.

If you are interested in reading more about the Fatimid caliphate, some up-to-date summary books and encyclopedia articles are:

- Brett, Michael (2017). The Fatimid Empire. The Edinburgh History of the Islamic Empires. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 978-0-7486-4076-8.

- Daftary, Farhad (1999). "Fatimids". In Yarshater, Ehsan (ed.). Encyclopædia Iranica. Vol. IX/4: Fārs II–Fauna III. London and New York: Routledge & Kegan Paul. pp. 423–426. ISBN 978-0-933273-32-0.

- Halm, Heinz (2014). "Fāṭimids". In Fleet, Kate; Krämer, Gudrun; Matringe, Denis; Nawas, John; Rowson, Everett (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam (3rd ed.). Brill Online. ISSN 1873-9830.

- Sanders, Paula (1998). "The Fāṭimid state, 969–1171". In Petry, Carl F. (ed.). The Cambridge History of Egypt, Volume 1: Islamic Egypt, 640–1517. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 151–174. ISBN 0-521-47137-0.

- Walker, Paul E. (1998). "The Ismā'īlī Da'wa and the Fātimid caliphate". In Petry, Carl F. (ed.). The Cambridge History of Egypt, Volume 1: Islamic Egypt, 640–1517. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 120–150. ISBN 0-521-47137-0.

- Walker, Paul E. (2018). "Fāṭimids". In Madelung, Wilferd; Daftary, Farhad (eds.). Encyclopaedia Islamica Online. Brill Online. ISSN 1875-9831.

Selected images

-

Image 1The Al-Hakim Mosque in Cairo, commissioned by al-Aziz in 990 and completed by al-Hakim in 1013 (later renovated in the 1980s by the Dawoodi Bohra) (from Fatimid Caliphate)

Image 1The Al-Hakim Mosque in Cairo, commissioned by al-Aziz in 990 and completed by al-Hakim in 1013 (later renovated in the 1980s by the Dawoodi Bohra) (from Fatimid Caliphate) -

.jpg) Image 2Al-Juyushi Mosque, Cairo, overlooking the city from the Muqattam Hills (from Fatimid Caliphate)

Image 2Al-Juyushi Mosque, Cairo, overlooking the city from the Muqattam Hills (from Fatimid Caliphate) -

Image 3Al-Salih Tala'i Mosque in Cairo, built by Tala'i ibn Ruzzik in 1160 and originally intended to house the head of Husayn (the head ended up being interred instead at the present-day al-Hussein Mosque) (from Fatimid Caliphate)

Image 3Al-Salih Tala'i Mosque in Cairo, built by Tala'i ibn Ruzzik in 1160 and originally intended to house the head of Husayn (the head ended up being interred instead at the present-day al-Hussein Mosque) (from Fatimid Caliphate) -

Image 4Fatimid ewer, 10th century CE (from Fatimid Caliphate)

Image 4Fatimid ewer, 10th century CE (from Fatimid Caliphate) -

Image 5Fragments of mosaic pavement from the palace of al-Qa'im in al-Mahdiyya (Mahdia), on display at the Mahdia Museum (from Fatimid Caliphate)

Image 5Fragments of mosaic pavement from the palace of al-Qa'im in al-Mahdiyya (Mahdia), on display at the Mahdia Museum (from Fatimid Caliphate) -

-

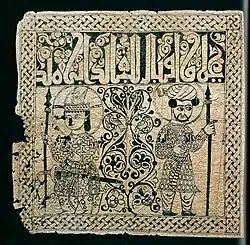

Image 7Image of two standing soldiers. 11th century, Fatimid period, from Fustat near Cairo. Museum of Islamic Art, Cairo, inv. no. 13703. Attribution to the Fatimid period is sometimes questioned. (from Fatimid Caliphate)

Image 7Image of two standing soldiers. 11th century, Fatimid period, from Fustat near Cairo. Museum of Islamic Art, Cairo, inv. no. 13703. Attribution to the Fatimid period is sometimes questioned. (from Fatimid Caliphate) -

Image 8Lustreware Plate with Bird Motif, 11th century. Archaeological digs have found many kilns and ceramic fragments in al-Fustat, and it was likely an important production location for Islamic ceramics during the Fatimid period. (from Fatimid Caliphate)

Image 8Lustreware Plate with Bird Motif, 11th century. Archaeological digs have found many kilns and ceramic fragments in al-Fustat, and it was likely an important production location for Islamic ceramics during the Fatimid period. (from Fatimid Caliphate) -

Image 9Cover page of the Leningrad Codex, a manuscript of the Hebrew Bible copied in Cairo/Fustat in the early 11th century (from Fatimid Caliphate)

Image 9Cover page of the Leningrad Codex, a manuscript of the Hebrew Bible copied in Cairo/Fustat in the early 11th century (from Fatimid Caliphate) -

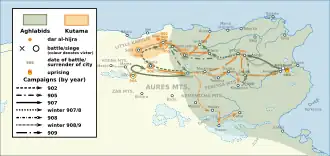

Image 10Map of Abu Abdallah's campaigns and battles during the overthrow of the Aghlabids (from Fatimid Caliphate)

Image 10Map of Abu Abdallah's campaigns and battles during the overthrow of the Aghlabids (from Fatimid Caliphate) -

.jpg) Image 11Architectural fragment from a bathhouse in al-Fustat, 11th century CE (pre-1168 CE). Museum of Islamic Art, Cairo, 12880. (from Fatimid Caliphate)

Image 11Architectural fragment from a bathhouse in al-Fustat, 11th century CE (pre-1168 CE). Museum of Islamic Art, Cairo, 12880. (from Fatimid Caliphate) -

Image 12Fatimid gold dinar minted during the reign of al-Mustansir Billah (1036–1094) (from Fatimid Caliphate)

Image 12Fatimid gold dinar minted during the reign of al-Mustansir Billah (1036–1094) (from Fatimid Caliphate) -

Image 13Men hunting, on ivory panel, 11th century (from Fatimid Caliphate)

Image 13Men hunting, on ivory panel, 11th century (from Fatimid Caliphate) -

Image 14Side chapel in the Hanging Church in Old Cairo, including frescoes (partly visible behind the screen here) dating from the late 12th or 13th century, before the church's later renovation (from Fatimid Caliphate)

-

-

Image 16Al-Azhar Mosque in Cairo, built by the Fatimids between 970 and 972 (from Fatimid Caliphate)

Image 16Al-Azhar Mosque in Cairo, built by the Fatimids between 970 and 972 (from Fatimid Caliphate) -

Image 17Bab al-Futuh, one of the gates of Cairo dating from Badr al-Jamali's reconstruction of the city walls (1987) (from Fatimid Caliphate)

Subcategories

- Select [►] to view subcategories

Subtopics

Associated Wikimedia

The following Wikimedia Foundation sister projects provide more on this subject:

-

Commons

Free media repository -

Wikibooks

Free textbooks and manuals -

Wikidata

Free knowledge base -

Wikinews

Free-content news -

Wikiquote

Collection of quotations -

Wikisource

Free-content library -

Wikiversity

Free learning tools -

Wiktionary

Dictionary and thesaurus