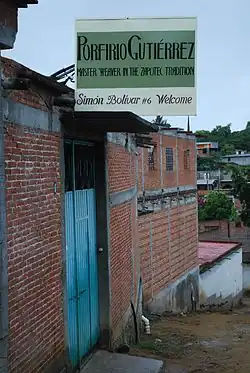

Porfirio Gutiérrez

Porfirio Gutiérrez | |

|---|---|

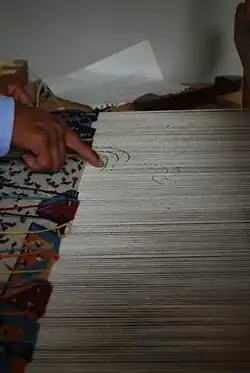

Gutiérrez at his loom in Teotitlán del Valle, Oaxaca | |

| Born | Teotitlán del Valle, Oaxaca, Mexico |

| Citizenship | Mexican |

| Children | 2 |

| Website | http://www.porfiriogutierrez.com/ |

Porfirio Gutiérrez is a California-based textile designer, artist, and natural dye expert who has studios in Ventura, California and in his hometown Teotitlán del Valle, Oaxaca where he specializes in the weaving traditions of his Zapotec community.[1] Gutiérrez’s artwork explores the intersection of Indigenous knowledge and contemporary art practice that emphasizes the physical geography of the Americas and its impact politically, culturally, and artistically. His focus on revitalizing and preserving traditional Zapotec dye techniques has been recognized by the Smithsonian Institution and Harvard University and he continues to use that knowledge to reinterpret traditional textile practices and materials in a modern context.[2][3] He subverts the traditional weaving language, and reimagines Mesoamerican symbols and forms, morphing them into his textile designs to reflect the architectural spaces and the urban environments of his home in California. He comes from a long line of traditional weavers, and his art practice remains dedicated to preserving the deep knowledge and spiritual practices of his Zapotec ancestors.[4] He grew up immersed in the colors of nature he found in the wilderness of Oaxaca’s mountains, and learned the sacred knowledge of medicinal plants. The intricate, geometric fretwork of the ancient ruin of Mitla, a sacred site for the Zapotec people, also informs the vernacular of Gutiérrez’s artistic symbolism. Mitla has been a touchstone for modern artists like Gutiérrez for generations. Gutiérrez points out that Josef Albers once said: “Mexico is a country for art like no other….the promised land for abstract art. For here it is already 1000s of years old.”[5] Gutiérrez’s art practice maintains his ancestor’s spiritual belief in nature as a living being, sacred and divine and he moves freely across the borders imposed between his two countries, as his ancestors and many other Indigenous peoples have done for thousands of years. His designs draw deeply upon his experiences of these two cultures as he moves between the traditional and the modern, but always relying on the deep knowledge that has been shared by his ancestors for generations.[6]

Current work

During his time in the United States, Gutiérrez did not weave, so when he returned to Teotitlán, the weaving and the culture behind it was a kind of rediscovery.[7] He reorganized the family workshop, with the main operations in Teotitlán and a studio in Ventura, California, called Indigenous Design Studio.[8]

His work is important to him not only to make a living but also to maintain contact with his roots.[9] He says that all of his pieces have a story to tell, often related to his ancestors, Zapotec heritage and Zapotec symbolism.[10] “When I say I am Porfirio Gutiérrez, this means nothing. It's no responsibility at all, but at the moment I say, I am a native of Teotitlán, a descendent of the Zapotec civilization, this brings forth a very large responsibility.”[11]

Since 2012, Gutiérrez has been doing research work on Zapotec textiles and natural dyes, along with ancient symbols from the Zapotec culture.[12][8] In 2015, he was selected for the Artist Leadership Program of the Smithsonian's National Museum of the American Indian .[9][13][14][2] This permitted him to study the institution's collections at the Cultural Resource Center in Suitland, Maryland.[12] Part of the program was a grant to work and share what he learned with his community. In 2016, Gutiérrez held a community workshop in Teotitlán. The aim of the workshop was to teach selected young people between the ages of 18 and 26 traditional dying and weaving techniques so that they do not die out.[13][12][15]

Gutiérrez is a master weaver whose work has been featured in publications, museums, and art galleries in the United States, Europe and Latin America.[9][11][16] These include The Work of Art: Folk Artists in the 21st Century, an honorary mention at Contemporary Indigenous Arts Biennale sponsored by CONACULTA.[13] His work can be found in the collections of LACMA, the National Museum of the American Indian, the Mingei International Museum, and the Tucson Museum of Art.[17] His dye materials are included in Harvard Art Museum's Forbes Pigment Collection. [18] The story of his art has been told in The New York Times, PBS, and the BBC World Service, London. Gutíerrez has been featured in Vogue Magazine and the Smithsonian’s American Indian Magazine.[19]

Gutiérrez's work has been exhibited in the United States, especially in California in institutions such as the Santa Fe International Folk Art Market, the Museum of Ventura County, the Maloof Foundation for Arts and Crafts, the Mexican consulate in Oxnard, the Casa Dolores in Santa Barbara and the Santa Barbara Arts Gallery. Outside the U.S., his works have appeared in Ecuador, Peru and Toronto. In Mexico, exhibitions include those at the Museo Nacional de Culturas Populares in Mexico City and the Casa de Cultura in Puebla. His first exhibition in Oaxaca was in 2016 at the family's compound.[11][16][7][20]

References

- ^ Kunath, Kate (2021-08-24). "The man preserving endangered colours". www.bbc.com. Retrieved 2025-07-16.

- ^ a b Mugits, Justin (Spring 2019). "Saving an Ancient Craft: Porfirio Gutierrez Returns Home". NMAI Magazine. Retrieved 2025-07-16.

- ^ Harvard (January 17, 2018). "A Colorful Tradition | Index Magazine | Harvard Art Museums". harvardartmuseums.org. Retrieved 2025-07-16.

- ^ Sánchez, Iriany (2021-03-10). "Porfirio Gutiérrez opens studio at Bell Arts Factory". LUM Art Magazine. Retrieved 2025-07-16.

- ^ "Josef Albers on Mexico, the promised land of abstract art". The Guggenheim Museums and Foundation. November 30, 2017. Retrieved 2025-07-16.

- ^ Tapper, Joan (April 2021). "Weaving an Identity: Porfirio Gutiérrez goes beyond tradition to craft his artistic vision". 805living.com. Retrieved 2025-07-16.

- ^ a b "Proyecto artístico de Porfirio Gutiérrez llega a Tucson". Univision television. January 15, 2016. Retrieved August 13, 2016.

- ^ a b "Weaving a Future in Teotitlan, Oaxaca". Hand-Eye magazine. December 8, 2011. Retrieved August 13, 2016.

- ^ a b c Tamara Koehler (January 29, 2016). "Ventura weaver's Smithsonian grant will help pass on old ways to new generation". Ventura County Star. Ventura, California. Retrieved August 13, 2016.

- ^ Brad Avery (April 18, 2016). "Framingham: Zapotec master weaver displays his artform at local restaurant". Metro West Daily News. Massachusetts. Retrieved January 15, 2016.

- ^ a b c Ivet Mendoza (July 29, 2016). "Teñido natural, herencia zapoteca que buscan preservar". Diario Marca. Retrieved August 13, 2016.

- ^ a b c "Porfirio Gutiérrez preserva la tradición y técnicas de telares". Mexico City: Agencia JM. July 29, 2016. Retrieved August 13, 2016.

- ^ a b c Elisa Ruiz. "Llegará Smithsoniano a Teotitlán del Valle en 2016 con Porfirio Gutiérrez". Sucedió en Oaxaca. Oaxaca. Retrieved August 13, 2016.

- ^ Melissa Dominguez (October 28, 2015). "Porfirio Gutierrez, Zapotec Master Weaver". First American Art magazine. Retrieved August 13, 2016.

- ^ "Se inauguró en Teotitlán del valle el taller "Reviviendo técnicas de teñido tradicional zapoteco"". MVM Television. Retrieved August 13, 2016.

- ^ a b "El artista indígena que convierte tejidos en obras arte". El Comercio. Lima, Peru. Retrieved January 15, 2016.

- ^ "Human". Porfirio Gutierrez. Retrieved 2025-07-16.

- ^ Schaffner, Ingrid. "Porfirio Gutiérrez, Cosmos/Continuous Line". Chinati. Retrieved 2025-07-16.

- ^ "PERSPECTIVES: Porfirio Gutierrez". Black Mountain College Museum + Arts Center. 2023-11-15. Retrieved 2025-07-16.

- ^ "Artists". Teotitlan del Valle, Oaxaca: Porfirio Gutierrez. Retrieved January 15, 2016.