Pompeu Fabra

Pompeu Fabra | |

|---|---|

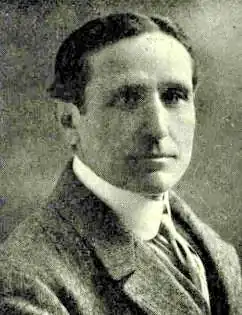

Pompeu Fabra in 1917 | |

| Born | 20 February 1868 |

| Died | 25 December 1948 (aged 80) Prada de Conflent, France |

| Education | University of Barcelona (Industrial Engineering) |

| Occupation(s) | Professor, engineer, linguist |

| Known for | Father of modern grammar of the Catalan language |

| Political party | Republican Left of Catalonia |

| Opponent | Francisco Franco |

Pompeu Fabra i Poch (Catalan pronunciation: [pumˈpɛw ˈfaβɾə]; Gràcia, Barcelona, 20 February 1868 – Prada de Conflent, 25 December 1948) was a Catalan engineer, linguist, and grammarian. He was the main author of the normative reform of the contemporary Catalan language and is considered the father of modern Catalan grammar. The Pompeu Fabra University in Barcelona is named after him.

Fabra was known as the "wise organizer of the Catalan language" for his pioneering work establishing the modern norms of the language.[1]

The Catalan writer Josep Pla wrote that "Fabra has been the most important Catalan of our time because he is the only citizen of this country, at this time, who, having set out to achieve a specific public and general goal, accomplished it in an explicit and indisputable way."[2]

Biography

Childhood

Pompeu Fabra was born in 1868 at number 32 Carrer de la Mare de Déu de la Salut, in the La Salut neighborhood of the former village of Gràcia, and later lived at 87 Carrer Gran de Gràcia. He was the son of Josep Fabra i Roca and Carolina Poch i Martí. He had twelve siblings and was the youngest of all; however, ten of them died, leaving only him and two sisters.

When he was five years old (1873), the First Spanish Republic was proclaimed in Spain, and his father, a republican, was elected mayor of the village.[3] Although the family moved to Carrer de la Diputació in Barcelona when he was six,[4] Fabra always remembered his Gràcia origins.[5]

His father had a strong influence on him during his childhood and youth, both through early contact with dictionaries and grammars circulating at home, such as the Diccionari de la llengua catalana ab la correspondencia castellana y llatina by Pere Labèrnia and the Gramática de la lengua catalana by Antoni de Bofarull and Adolf Blanch,[6] and through choosing his career path as an engineer, a decision influenced by his father, who unfortunately did not live to see it completed, having died in 1888.[7]

Fertile and controversial beginnings

Fabra began studies in industrial engineering, which he gradually combined with a strong self-taught interest in philology. In 1889, he joined as an editor at L'Avenç, which in 1891 published through its editorial the grammar Ensayo de gramática del catalán moderno. This was the first time, using a scientific methodology, that the spoken language was described with careful phonetic transcription.

Together with Joaquim Casas Carbó and Jaume Massó i Torrents, Fabra undertook the second linguistic campaign of L'Avenç, which lasted throughout 1892. It consisted of a series of dense, generally unsigned notes published under the heading «La Reforma Lingüística» starting in the March issue. These articles «provided a theoretical justification for the orthographic changes being gradually adopted».[8] These were the first scientific attempts to systematize the language, which caused heated controversies and formed the outline of the future standardization.[9] In L'Avenç, Pompeu Fabra published articles under the pseudonym Esteve Arnau, to avoid direct confrontation and criticism of real people with established careers at the time, as well as to conceal his participation in a magazine from which he felt ideologically distant.[10]

Nonetheless, these proposals were considered revolutionary and difficult to accept by the traditional majority, including the floralists, some of the most renowned writers of the Renaixença such as Narcís Oller, Víctor Català, and Àngel Guimerà, as well as the press.[11] The campaign in L'Avenç provoked a reaction from the traditionalists, who counterattacked — which was precisely what the campaign's promoters sought. A clear example was Fabra’s article in La Vanguardia on 22 March 1892 titled «Sobre la reforma lingüística y ortográfica» (“On Linguistic and Orthographic Reform”), in which he responded to an earlier article by Omar y Barrera in the same newspaper and summarized his program of action.

In 1895, Fabra submitted Contribució a la gramàtica de la llengua catalana to the special prize for best grammar at the Jocs Florals of 1895, which opposed his theories and was left vacant. He submitted it again in 1896, when the jury awarded him an honourable mention. The work was not published until 1898 by the Tipografia de L'Avenç[12] because Fabra feared a trap if it was published by the Jocs Florals commission.[13] The work is considered a crucial milestone in the grammar codification of modern Catalan.[13]

From Bilbao to Badalona

In 1902, he obtained by competitive examination the chair of chemistry at the School of Engineering in Bilbao. On 5 September 1902, he married Dolors Mestre at the Church of Sant Vicenç in Sarrià, shortly before the academic year began. The couple stayed in Bilbao for ten years, where they had three daughters: Carola (Bilbao, 1904–1998), Teresa (Bilbao, 1908–1948), and Dolors (Bilbao, 1912–1993).[14] Despite being far from Catalonia, during those years he intensified his dedication to philology. In 1912, after holding a chair at the University of Bilbao, he decided to resign from his position and return to Catalonia to devote himself fully to linguistic work, which he had never entirely abandoned, even while living in the Basque Country. The Fabra family did not settle in Barcelona, but in Badalona. One of the main reasons for Fabra’s decision was his middle daughter Teresa’s delicate health; doctors had recommended sea air and frequent sea baths. Badalona, located right on the coast, provided this proximity to the sea along with convenient access to his work at the university and the Institute of Catalan Studies. Furthermore, since his time living in Begoña, Fabra preferred living in smaller towns, away from the hustle and bustle of large capital cities.[15] He lived in Badalona until he was forced into exile in 1939[16] and was an active member of the local community. He became the first director of the Municipal School of Arts and Crafts, where he befriended other teachers and colleagues, such as Pau Rodon i Amigó. Numerous anecdotes became popular in the city, especially regarding the discussions he used to have with friends and acquaintances during his regular tram commutes between Badalona and Barcelona, a mode of transport he was particularly fond of.

In 1906, he participated in the First International Congress of the Catalan Language with the paper Qüestions d'ortografia catalana ("Questions of Catalan Orthography"). His intellectual prestige was greatly enhanced, to the point that Prat de la Riba invited him to lead a project to standardize the Catalan language. He returned to Catalonia, was appointed a founding member of the Philological Section of the IEC, and was awarded a chair at the Estudis Universitaris Catalans. In 1912, he published a Gramática de la lengua catalana, still in Spanish; a year later, he released the Normes ortogràfiques (1913), a broad orthographic reform issued by the Institute of Catalan Studies.[17] While the reform gained significant support, it also sparked strong opposition.[18] One of the fundamental principles of Fabra’s orthography was respect for both the pronunciation of the dialects and the etymology of words. The Diccionari ortogràfic (1917), published by the Institute of Catalan Studies under his direction, completed the 1913 Normes and served as the official codification of Catalan orthography.[19]

An effective mastery

Starting in 1918, with the publication of the Catalan Grammar (Gramàtica catalana), which was practically adopted as official, a new stage began that culminated in 1931[20] with the publication of the General Dictionary of the Catalan Language (Diccionari general de la llengua catalana). That same year, Fabra also released the Intermediate Course of Catalan Grammar (Curs mitjà de gramàtica catalana), aimed particularly at schools, which was later reissued in 1968 as Introduction to Catalan Grammar (Introducció a la gramàtica catalana).

The Philological Conversations (Converses filològiques, 1924) arose from Fabra’s desire to popularize his linguistic reflections. These were relatively short articles originally published in the republican newspaper La Publicitat, addressing and resolving frequent language doubts. The notes served as practical lessons, written in a spontaneous style in response to queries from readers, establishing a direct and close rapport.[21]

In 1925, Fabra began working for the Provincial Council of Barcelona (Diputació de Barcelona), specifically in the Department of Public Instruction and Fine Arts. In 1927, he was appointed professor of Catalan Prosody at the Institut del Teatre.[22]

Fabra's pedagogical influence in some areas of the Girona region became evident in the early 1930s. His relationship with Ignasi Enric Jordà i Caballé (1886–1977), a priest and professor of Catalan grammar at the Normal School of Girona, led to Fabra giving lectures and offering grammar lessons, either in person or by correspondence.

One notable event was the Catalan Grammar Course held in Santa Coloma de Farners in the summer of 1931. The registration leaflet from the organizing committee stated: “Given the great interest aroused throughout Catalonia in the teaching of Catalan, Santa Coloma cannot be left behind; thus, a Catalan Grammar Course has been organized.”[23] Fortunately, a photograph of the course’s closing session has been preserved, illustrating the event’s success. Among those pictured are Joan Vinyoli and Fabra himself.

Consolidation of a task

In 1932, Fabra directly obtained, due to his prestige, the chair of Catalan language at the University of Barcelona. With him, the Catalan language officially entered the university for the first time in history. In 1933, Fabra became president of the board of trustees of the newly created Autonomous University of Barcelona. The dictionary of 1932, already mentioned, and popularly known as Diccionari Fabra or el Pompeu, was conceived as the draft –«canemàs» ("framework"), as Fabra himself called it– of a future official dictionary of the Institute of Catalan Studies. The criteria that governed the making of the dictionary can be summarized as follows:

- Exclusion of archaisms and dialectalisms of rather restricted scope.

- Forecast of eliminating words that, over time, might lose validity.

- Non-admission of foreign words borrowed from other languages that replaced genuine Catalan words or prevented the creation of new ones.

- Incorporation of technical words, previously adapted into Catalan, of Greco-Latin origin and universal scope.

Last years

In 1934, he was arrested following the October events as head of the University Board, along with the rest of the members of the body. They were imprisoned on the prison ship Uruguay, where the Catalan Government was also held. He remained imprisoned there for six weeks and one day. On December 8, his case was dismissed and he was released. However, it is noteworthy that during his captivity, he did not abandon his work; with permission from the ship's authorities, he gave some lectures, which were attended by imprisoned politicians and intellectuals and impressed the guards.[24]

In 1934, he was one of the signatories of the manifesto "For the Conservation of the Catalan Race." This racist manifesto fits the period when human eugenics was a negotiable topic, but in Nazi Germany at that time, it led to industrial-scale murders of Jews, homosexuals, Roma and Sinti people, and other excesses.[25]

In 1937, he published Les principals faltes de gramàtica (The Main Grammar Errors), a popular science book about language, edited by Editorial Barcino as part of the Barcino Popular Collection, revised by Fabra and co-written with Jeroni Marvà (pseudonym of Artur Martorell and Emili Vallès) and Bernat Montsià (pseudonym of Cèsar August Jordana i Mayans).[26]

In the winter of 1939, he went to the house in Sant Feliu de Codines, from where he left for exile in France.[16] Although he was not personally persecuted, due to the unstable situation it became increasingly difficult to live in Catalonia, and his status as a Republican and Catalan nationalist made him leave. Before leaving, he met with some colleagues, such as Joan Oliver and Antoni Rovira i Virgili, to decide to continue the work of the Institut d'Estudis Catalans (Institution of Catalan Letters), whether inside or outside Catalonia. Finally, in the early hours of January 24, the Fabra family left their home, Can Viladomat, heading to Girona, then to Bescanó, Olot, and Agullana, where refugees began arriving a few days later.[27] They crossed the Franco-Spanish border on January 31, 1939, five days after General Francisco Franco's troops entered Barcelona. Afterwards, he lived a long pilgrimage with stays in Paris, Montpellier, Perpignan, and finally Prades, at number 15 Marxants Street.[28]

On January 30, 1940, the provincial court of political responsibilities in Barcelona opened a file – number 2223 – against the publisher Josep Queralt i Clapés and him as suspects of Catalan nationalist affiliation. The Civil Guard accused him of being a "staunch separatist element," a verdict later confirmed by the regional court, which labeled him "hostile to Spanish matters." On May 10, 1941, a sentence was issued. Pompeu Fabra was fined 5,000 pesetas for his Catalanism "and profound contempt and enmity towards Spain," accompanied by "an absolute, perpetual, and strangely everlasting disqualification from national territory." However, Pompeu Fabra's financial situation led Judge Francisco Eyre Varela to declare his insolvency on October 15, 1941. On March 15, 1947, the Audiencia Provincial de Barcelona annulled the sentence. Eleven years later, the liquidation commission of the regulations pardoned him and restored his honor, albeit posthumously.[29]

Between September 14, 1945, and January 22, 1948, he held the position of counselor of the Government of Catalonia in exile.[30]

The last years of his life were very precarious, living thanks to food and clothes that were sent to him.[31][31] Despite adverse conditions, he continued working and completed a new Catalan Grammar, published posthumously in 1956[32] by Joan Coromines, and the Philological Conversations.[31]

In 1947, his daughter Teresa was diagnosed with cancer, a fact that deeply upset him; it made him aware of his age and led him to think often about death. So much so that on November 27, 1947, he went to Andorra to make his will.[33] The death of his daughter affected Pompeu Fabra deeply; he was about to turn 80 years old.[34] The words of Joan Alavedra at his funeral reflected the feelings of the community of Catalan exiles who had been preparing a celebration for the philologist’s eightieth birthday, turned into mourning for the family loss.[35] Nevertheless, the tribute for his eightieth birthday was finally held, and the Catalan community in exile gave him a gold medal purchased by popular subscription, with his bust modeled by the sculptor Joan Rebull.[36]

He died at his residence in Prades on December 25, 1948.

Civic life

Ateneu Barcelonès

He was linked throughout his life to the Ateneu Barcelonès. He joined as a resident member in 1891,[37] registered in the literature section.[38] He resigned and rejoined several times. He renewed his resident membership at Ateneu Barcelonès on June 13, 1913.[39] He was a member until June 1938, a year managed by the Association of Ateneistes of Barcelona, and from this date his membership is lost in the records of the Ateneu Barcelonès Historical Archive.[40]

He was president of the Ateneu Barcelonès between 1924 and 1926. The Ateneu archive preserves two photographs and various letters and writings by Fabra.[41]

Sport

Fabra considered sport indispensable for the formation of the person and the articulation of the nation, and he was the top leader of Catalan sport during the years of the Republic, until he ceased his activity when the Spanish Civil War broke out.[42] He always regarded sports from the perspective of physical education and leisure, without emphasizing the competitive aspect.[43]

When he returned to Catalonia in 1914, he was one of the founders of the Badalona Lawn-Tennis Club, of which he was president.[44] Later, he was elected president of the Lawn Tennis Association, today known as the Catalan Tennis Federation.[45] In 1933, when the Catalan Union of Sports Federations was created, he became its first president.[46] Additionally, he was part of the tennis section of FC Barcelona. He usually played tennis on the courts belonging to the chemical factory Cros in Badalona, together with his daughter Carola.[45][47]

In an interview, he spoke about the importance of tennis in Catalonia: "Our land is one of the main centers in the Peninsula. The others are Madrid, the Basque Country, Huelva, and now it is starting to grow in other cities. Tennis in Catalonia has reached a remarkable level of importance and prestige, not only due to the growing number of people who play it, but also because of the excellent quality of many players, which surpasses that of the best from other mentioned places."[45]

With his presidency of the Catalan Union of Sports Federations, Fabra became the top leader of Catalan sport during the years of the Second Spanish Republic, until he ceased his activity when the Spanish Civil War broke out.[48]

Legacy

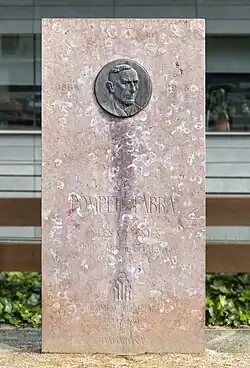

Every year, his tomb in the Cuixà monastery near Prada is visited by thousands of Catalans.

The Universitat Pompeu Fabra in Barcelona bears his name.[49]

The metro station in Barcelona Badalona Pompeu Fabra (Barcelona Metro) bears Pompeu Fabra's name and legacy.

Books

- Tractat de ortografia catalana (1904)

- Qüestions de gramàtica catalana (1911)

- La coordinació i la subordinació en els documents de la cancilleria catalana durant el segle XIV (1926)

- Diccionari ortogràfic abreujat (1926)

- La conjugació dels verbs en català (1927)

- Diccionari ortogràfic: precedit d'una exposició de l'ortografia catalana (1931)

- El català literari (1932)

References

- ^ "Fabra according to Josep Pla". Archived from the original on 31 August 2019. Retrieved 31 August 2019.

- ^ "Fabra segons Josep Pla" (in Catalan). Archived from the original on 31 August 2019. Retrieved 31 August 2019.

- ^ Miracle 1968, pp. 10–11.

- ^ Miracle 1968, pp. 14–15.

- ^ García, Pilar. "Pompeu Fabra, an illustrious linguist... and hiker". El Periódico de Catalunya. Barcelona. Retrieved 19 April 2012.

- ^ Miracle 1968, pp. 26–27.

- ^ Miracle 1968, p. 34.

- ^ Bonet, Joan (1993). Els inicis de la lexicografia catalana moderna. Barcelona: Universitat de Barcelona. p. 24.

- ^ Ramon Pla i Arxé. "L'Avenç: the Modernization of Catalan Culture". Universitat Oberta de Catalunya. Archived from the original on 2008-10-17. Retrieved 2008-03-01.

- ^ Murgades, Josep (2005). Textos desconeguts de Fabra. Punctum. ISBN 9788493480202.

- ^ Guifreu, Josep. "Pompeu Fabra and the Press in the Standardization Processes of Modern Catalan". Pompeu Fabra University. Archived from the original on 2021-05-10. Retrieved 2021-05-09.

- ^ Mir, Jaume; Sola, Joan (2005). Pompeu Fabra: A Life in Defense of the Catalan Language. Barcelona: Edicions 62. p. 175.

- ^ a b Mir, Jaume; Sola, Joan (2005). Pompeu Fabra: A Life in Defense of the Catalan Language. Barcelona: Edicions 62. pp. 175–176.

- ^ Paloma, David; Montserrat, Mònica (September 2018). L'abecé de Pompeu Fabra. Cerdanyola del Vallès (Barcelona): Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, Servei de Publicacions. p. 140. ISBN 978-84-490-8037-1.

- ^ Miracle 1968, p. 89.

- ^ a b Franquesa 2010, p. 79.

- ^ Massot i Muntaner, Josep (1985). Antoni M. Alcover i la llengua catalana. L'Abadia de Montserrat. p. 153. ISBN 8472027457.

- ^ Massot i Muntaner, Josep (1985). Antoni M. Alcover i la llengua catalana. L'Abadia de Montserrat. p. 153. ISBN 8472027457.

- ^ "Chronology – Diccionari ortogràfic (1917)". Generalitat de Catalunya – Any Pompeu Fabra. Retrieved 5 August 2025.

- ^ "El Fabra del 31". Archived from the original on 2023-03-25.

- ^ "Pompeu Fabra, llengua, esport i esnobisme (1922–1924)". Universitat Pompeu Fabra. 2012-11-29. Archived from the original on 2021-11-24. Retrieved 2018-11-29.

- ^ Serra, Joan (May 2018). "2018: Any Pompeu Fabra" (PDF). Farella (in Catalan). Ajuntament de Llançà. p. 5. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2024-06-06. Retrieved 2023-10-22.

- ^ Figueras i Capdevila, Narcís; Puigdemont i Casamajó, Joaquim (2010). "Ignasi Enric Jordà i Caballé (1886–1977) and the promotion of the Catalan language in the 1920s and 1930s. The Santa Coloma de Farners course (1931)". Quaderns de la Selva, no. 22, Centre d'Estudis Selvatans: 99–144.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Miracle 1968, pp. 105–106.

- ^ "Research Gate". Archived from the original on 2023-08-03.

- ^ Jordi Badia i Pujol (2018-02-20). "Ten books (and a surprise) to know who Pompeu Fabra was". VilaWeb (in Catalan). Retrieved 2024-09-24.

- ^ Paloma, David (2016-01-25). "The Republican Exile of Pompeu Fabra". Núvol. Archived from the original on 2018-11-30. Retrieved 2020-02-15.

- ^ Bassas, Antoni (2018-02-17). ""Thank you Fabra, watch over us from Prades"". Ara.cat. Archived from the original on 2018-02-20.

- ^ Espiga Corbeto, Francesc (2014-02-27). "A 5,000 peseta fine to Pompeu Fabra". El Punt Avui.

- ^ Cetit. "Engineers Tarragona - Pompeu Fabra, creator of the official Catalan dictionary and chemical industrial engineer" (in Catalan). Retrieved 2024-08-24.

- ^ a b c "The last years of Pompeu Fabra, with exile more present than ever". Vilaweb. 2018-02-19. Archived from the original on 2018-11-30. Retrieved 2018-11-29.

- ^ Franquesa 2010, p. 68.

- ^ Segarra, Mila (1998). "Notes from a life dedicated to language" (PDF). Nadala. Fundació Jaume I: 37. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2018-12-01.

- ^ "Pompeu Fabra's ABC". Archived from the original on 2018-11-30. Retrieved 2018-12-01.

- ^ "Teresa Fabra has died" (PDF). La Humanitat. 1948-02-05. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2018-12-01. Retrieved 2018-12-01.

- ^ Segarra, Mila (1998). "Notes from a life dedicated to language" (PDF). Nadala. Fundació Jaume I: 37. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2018-12-01.

- ^ "Board meeting minutes, December 4, 1891". Archived from the original on 2020-03-26. Retrieved 2024-08-24.

- ^ "Membership records, Ateneu Barcelonès archive". Retrieved 2024-08-24.

- ^ "Membership renewal records, June 1913". Retrieved 2024-08-24.

- ^ "Membership registry, Ateneu Barcelonès Historical Archive". Retrieved 2024-08-24.

- ^ "In defense of culture: the great speeches of Ateneu Barcelonès with ARA". Archived from the original on 2020-03-26. Retrieved 2024-08-24.

- ^ "Catalan sport involved in the celebration of the Fabra Year". Archived from the original on 2018-11-30. Retrieved 2018-11-29.

- ^ "Fabra and sport: from the social dimension to terminological contribution". Archived from the original on 2018-11-29. Retrieved 2018-11-29.

- ^ Franquesa 2010, p. 78.

- ^ a b c Franquesa 2010, p. 25.

- ^ Santacana, Carles (2013). Pompeu Fabra: 10 aspects of the man and the work. Barcelona: Galerada. p. 85. ISBN 978-84-96786-56-1.

- ^ "The lesser-known Pompeu Fabra". Biblioteca de Catalunya. 2018-05-02. Retrieved 2019-01-01.

- ^ Mir, Jordi (2010). "Fabra and sport: from the social dimension to terminological contribution". Terminàlia (1): 71–77. doi:10.2436/20.2503.01014.

- ^ "Sobre la Universitat Pompeu Fabra: Qui era Pompeu Fabra?" (in Catalan). Pompeu Fabra University. Retrieved 2025-06-21.

Bibliography

- Franquesa, Montserrat (2010). Badalona i Pompeu Fabra. Ajuntament de Badalona.

- Miracle, Jaume (1968). Pompeu Fabra. Barcelona: Editorial Selecta.

- Fabra, Pompeu (2009-10-14). Costa Carreras, Joan (ed.). The Architect of Modern Catalan: Pompeu Fabra (1868-1948). Translated by Yates, Alan. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing. ISBN 978-90-272-8924-7.

External links

- "Pompeu Fabra i Poch". Gran Enciclopèdia Catalana. Enciclopèdia Catalana. (in Catalan)

- Biographical notice by Josep Pla (in Catalan)