Philosophy of New Music

| Author | Theodor W. Adorno |

|---|---|

| Original title | Philosophie der neuen Musik |

| Translator | English: Anne G. Mitchell and Wesley V. Blomster (1973); Robert Hullot-Kentor (2006) |

| Language | German |

| Genre | Philosophy, musicology, social criticism |

| Published | 1949 |

| Publication place | Germany |

| Media type |

Philosophy of New Music (German: Philosophie der neuen Musik) is a work written by Theodor W. Adorno, first published in 1949,[1] in which avant-garde music is discussed in light of the challenges to artistic function and authenticity posed by the culture industry.

Content

The text consists of three main parts, specifically, the introduction and two main sections focusing predominantly on the composers Arnold Schoenberg and Igor Stravinsky, respectively.

In the introduction, Adorno presents the issue motivating the text, namely, the increasing commodification of art in the era of mass culture. While the abstract nature of music made it initially more resistant to the influences of the culture industry than other art forms, technological developments that enabled the setting of music as mere accompaniment to film and radio led to its general degradation into kitsch. The only musical works still capable of resisting are avant-garde works, which critically question the application of musical tradition in the post-World War II era.

Schoenberg and Progress

Adorno begins with a general description of the problematic use of tonality in contemporary composition: the employment of pleasant and familiar tones can no longer bear true witness to historical reality. The use of old musical forms inherited from the Romantic era is also problematic, as they present a semblance of unity between the subject and object that, in Adorno's view, is no longer possible in light of history. For Adorno, it is rather the fragmented musical work, in which the conflict between form and the historically and socially derived musical material is revealed, that is most true.

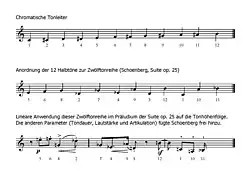

Schoenberg's use of atonality, and later development of the twelve tone-technique illustrates his search for a solution. The principle underlying twelve-tone-technique is the use of a “row” of twelve tones that represent the pitch classes of the chromatic scale.

The composition is constructed based a “row”, or basic sequence of the twelve tones, with the general rule that all twelve tones must be used before individual tones can be repeated (see image for example of row used in Schoenberg's Suite for Piano, op. 25). The basic row can be followed by a reversal or retrograde form of the initial row, or alternatively derivations of the row, and compositions may also utilize two or more rows.

The composer employs the twelve-tone-technique in an attempt to recover spontaneous subjective expression, but the constraints of the system instead lead to a meaningless result, argues Adorno, drawing a parallel between man's subjugation of nature and the subjugation of musical material in composition by the twelve-tone-technique. In order for the rules to be productive, the artist must have a confrontation of the rules with the concrete form of the musical material. Once the rules are accepted without question, they lose their significance for instance, the use of specific intervals between notes, such as the dissonant minor second, previously defined melody and conferred musical meaning, but with the rules governing twelve-tone-technique, intervals are to some extent predetermined and lose their shock value.

Yet, Adorno does not completely disregard the twelve-tone-technique, and in fact describes it as the path forward for contemporary music, naming the late works of Schoenberg, as well as Alban Berg's opera Lulu, as successfully overcoming the rigidity of the twelve-tone-technique and achieving subjective expression.

Stravinsky and Restoration

While Adorno observes that Schoenberg and Stravinsky share the fundamental objective of restoring authenticity in new music, he finds Stravinsky's method problematic in its employment of old forms.

The use of established archaic forms is appealing in that it presents the possibility of regression to a more primitive, infantile stage in order to restore authenticity in art. In Adorno's view, however, the strict application of external structure takes on a meaningless ritualized character, effectively obliterating subjectivity from the resulting musical work. The annihilation of the subject and its dissolution into the crowd is also evidenced for Adorno in the subject matter of Stravinsky's works, including Petrushka as well as The Rite of Spring, with its depiction of pagan sacrifice.

Historical and Philosophical Context

The work was largely composed during the period in which Adorno resided in American exile,[2] and was the first book he published in post-Nazi Germany.[3] An early version of the first section that focused only on Schoenberg was written in 1940-41, though it was not published and was distributed only within the Institute for Social Research in New York. Following Adorno's decision to publish the work in Germany, a second section about Stravinsky was added, and the first section was revised to include Schoenberg's late works.[4]

Adorno provided Thomas Mann with the unpublished manuscript of Philosophy of New Music in 1943, among other resources, in response to the latter's request for assistance in developing the musical aspects of the composer figure in his novel Doctor Faustus.[5] Although the novel itself does not explicitly credit Adorno, Mann's The Story of a Novel: The Genesis of Doctor Faustus [6] and the published correspondence between Adorno and Mann [7] describe the extent of their collaboration.

Philosophy of New Music is hardly the only text in Adorno's oeuvre to concern itself with music. As Adorno scholars have noted, these works do not merely concern themselves with questions of aesthetic value. Given Adorno's fundamental position that art cannot be seen independent of its relationship to society, it follows that much of his sociological and political critique is also extensively illustrated in his apparently musical texts.[8]

Several themes that are mentioned in the Philosophy of New Music, such as artistic “truth content” (Wahrheitsgehalt), are further developed in his later works on the philosophy of aesthetics, including the posthumously published Aesthetic Theory.[9]

Reception

Philosophy of New Music was received controversially from its initial publication. While the book received some praise,[10] other reviews were more negative, particularly with regard to the portrayal of Stravinsky.[11] Schoenberg's private letters indicate that he also viewed the book critically.[12] Adorno responded to some of these critiques in an article published in the Melos journal in 1950, attempting to clarify some possible misunderstandings of the work's content and intentions.[13]

More recent scholarship ground these early accusations in Adorno's relatively less musicological and more psychological analysis of Stravinsky's works than of Schoenberg [14] as well as a tendency to oversimplify Adorno's position as pro-Schoenberg and anti-Stravinsky.[15]

Editions and Translations

Adorno first published the text in 1949 in J. C. B. Mohr (Paul Siebeck) Verlag. Europaischen Verlagsanstalt published the second and third edition in 1958 and 1966, respectively, and an author's note was added to the third edition to contextualize the work in contemporary musical developments as well as his own later musical writings. The fourth edition was published by Ullstein Verlag in 1972, and the fifth edition, first published in 1975 by Suhrkamp Verlag, includes Adorno's response to critique from the Melos journal.[16]

The first English translation by Anne G. Mitchell and Wesley V. Blomster was published in 1973 by Seabury Press, and the second by Robert Hullot-Kentor in 2006 by the University of Minnesota Press.[17]

References

- ^ Adorno, Theodor W. (2006). Philosophy of New Music. Translated by Robert Hullot-Kentor. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. ISBN 978-0-8166-3666-2.

- ^ Adorno, ix.

- ^ Adorno, 169.

- ^ Adorno, ix.

- ^ Adorno, Theodor W., and Thomas Mann (2006). Correspondence, 1943-1955. Edited by Christoph Gödde and Thomas Sprecher. Translated by Nicholas Walker. Malden, MA: Polity Press. p. 3-5. ISBN 0 7456 3200 9.

- ^ Mann, Thomas (1961). The Story of a Novel: The Genesis of Doctor Faustus. Translated by Richard and Clara Winston. New York: Knopf. pp. 125–6. ISBN 0394447352.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ^ Adorno and Mann, 3-25.

- ^ Paddison, Max (1993). Adorno's Aesthetics of Music. New York: Cambridge University Press. p. 16. ISBN 0 521 43321 5.

- ^ Paddison, 56-57.

- ^ Franck, Wolf (1950). "Review: Philosophie der Neuen Musik by Theodor W. Adorno". Journal of the American Musicological Society. 3 (3): 279–285.

- ^ Adorno, 166-168.

- ^ Adorno, xxiii-xxv.

- ^ Adorno, 165-168.

- ^ Marsh, James L. (1983). "Adorno's Critique of Stravinsky". New German Critique. 28: 147-169.

- ^ Van Eecke, Livine (2014). "Adorno's Listening to Stravinsky - Towards a Deconstruction of Objectivism". International Review of the Aesthetics and Sociology of Music. 45 (2): 243–260.

- ^ Adorno, 169-170.

- ^ Adorno, xviii.