Phelipe Medrano

Don Phelipe Medrano | |

|---|---|

Coat of arms of the House of Medrano | |

| Native name | Phelipe Medrano |

| Born | fl. 1744 Spain |

| Occupation | Mathematician, author, court noble |

| Language | Spanish |

| Nationality | Spanish |

| Citizenship | Spanish Empire |

| Period | 18th century |

| Genre | Court mathematics, poetic offering |

| Subject | Magic squares, noble ascent, symbolic mathematics |

| Literary movement | Enlightenment Spain |

| Years active | 1744–1745 |

| Notable works | Quadrados mágicos |

| Relatives | House of Medrano |

| Signature | |

Phelipe Medrano (fl. 1744) was an 18th-century Spanish nobleman and mathematician from the House of Medrano, knight of the Order of Santiago and author of Quadrados mágicos, que sobre los que figuraban los Egyptcios, y Pythagoricos (1744), a printed work dedicated to Queen Isabel Farnese that compiles over one hundred structured magic squares and cubes. Presented as a mathematical offering, the book functions as doctrine and a coded expression of loyalty, hierarchy, and courtly advancement. It was approved by Diego de Torres Villarroel and accompanied by sonnets from members of Madrid's literary academies during the Age of Enlightenment.[1]

A second manuscript, Solución general y natural de los Quadrados mágicos (1745), expands the project into a formal sequence of definitions and theorems.[2] Together, Medrano's works enact a visual and numeric logic of noble service and delegated order that reflects the same precepts articulated in República Mista (1602) by Tomás Fernández de Medrano and Mirror of Princes (1657–1661) by Diego Fernández de Medrano, anchoring Phelipe's work within this legacy in early Bourbon Spain.[3]

Life and Background

Phelipe Medrano was the son of Pedro Medrano, a knight of Santiago, an illustrious member of the House of Medrano, and crown official.[1] The House of Medrano were deeply embedded in the Order of Santiago, with multi-generational nobles maintaining important roles in the Order for centuries.[4] Active in the court of early 18th-century Bourbon Spain, Phelipe identified himself as a knight of the Order of Santiago, like his father before him. While no birth record has been located, his position and status are evident in the courtly dedication, poetic endorsements, and structural design of his printed treatise, Quadrados mágicos (1744).[1]

The House of Medrano's deep involvement in the Military Orders of Spain, particularly the Order of Santiago, culminated in 1605 when Philip III of Spain reformed the Order of Santiago with the works of García de Medrano y Castejón, enacting one of the most comprehensive reforms of their statute laws.[5] By the 18th century, Phelipe, Pedro, and other noblemen of the Medrano family continued this tradition, holding the rank of knight of the Order of Santiago and serving on the Royal Council of Orders.[4] Pedro was active during the same period as Giovanni Antonio Medrano, also known as Juan Fernández de Medrano, who served as royal architect and tutor to the Bourbon princes.[6] According to the Heraldrys Institute of Rome, the Medrano family is well known "for its antiquity, its splendor, for their military prowess and virtue and for every other value of chivalry that prospered with this family, in great numbers, magnificent and generous."[7]

Pedro Medrano

The clearest testimony to Phelipe Medrano's lineage appears in a printed elogio included in the prefatory section of Quadrados mágicos, authored by the This praise comes from Ignacio de Loyola y Oyanguren, a celebrated writer born 9 February 1686, who inherited the title of 2nd Marqués de la Olmeda,[8][1] Himself a Knight of Santiago and royal official, the marqués offers praise for the author's father, Pedro Medrano, citing his titles and offices in full:

Pedro Medrano; knight of the same Order, secretary to His Majesty, and senior second official of the Secretariat of State for the Negotiation of Italy, and of the Universal Dispatch Office with authority over the exercise of decrees.[9]

The 2nd Marqués de la Olmeda, Cavalier of the Order of Santiago, Commander of Villa-Rubia de Ocaña, and Procurador General of said Order,[10] personally confirms that Phelipe's work was received not merely as a mathematical curiosity, but as a continuation of a family tradition of noble service.[1]

In the elogio of Phelipe Medrano's Quadrados Magicos, the Marqués de la Olmeda describes Philip's father Pedro as a "living archive of history... a Caliodorus (Cassiodorus) of the world," a celebrated state counselor, and the source of the author's intellectual inheritance.[1]

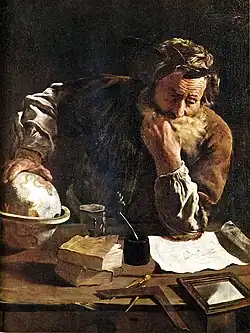

.jpg)

The elogio elaborates on this legacy with the following verses:

Since your father, in brief, Granted you the improvement of third and fifth, Your father, whose glory Was a living Archive of History, And in affairs of State, A Caliodorus of the world, celebrated far and wide, What wonder, then, if my rough wit Should stand in awe of a branch sprung from such a trunk?[1]

His father, Pedro Medrano, held the post of Secretary to His Majesty, and the highest-ranking Second Official of the Secretary of State for Italy (the highest post below the Secretary of State himself) during the reign of Charles II (r. 1665–1700), having previously served as Secretary of War for the Navy.[11]

Contemporary documentation confirms his high-level role in Spanish foreign policy. In March 1672, Antonio de Mendoza, newly appointed envoy to Genoa, addressed Medrano's father with deference:

I acknowledge having received notice from the President [of the Council], following whose dispatch I have requested, by way of my signature, as a means of ensuring that this matter may proceed as is fitting, safeguarding my position. May God keep Your Grace for many years.[12]

A month later, Lope de los Ríos, President of the Council of the Treasury, formally instructed Pedro Medrano to authorize Mendoza's travel allowance by royal order. This document, held in the Spanish Archives, reveals Pedro's responsibility for coordinating and executing diplomatic policy at the state level.[13]

Continuity

While Pedro's distinguished service took place under the last Habsburg monarch, Charles II, Phelipe Medrano's Quadrados mágicos appeared at the Bourbon court under Philip V (r. 1700–1746), maintaining the continuity of Medrano family service across dynastic transitions. The numerical structures in Phelipe's work reflect the same values of order, balance, and hierarchy that underpinned his father's political and diplomatic roles.[1]

Works

Quadrados mágicos (1744)

.jpg)

Phelipe Medrano, knight of the Order of Santiago and son of Pedro Medrano, Secretary of the Council of State for Italy, is best known for his 1744 treatise Quadrados mágicos, que sobre los que figuraban los Egyptcios, y Pythagoricos. Printed in Madrid and dedicated to Queen Elisabeth Farnese, the work presents over one hundred magic squares, from 3×3 to 32×32, not as mathematical curiosities but as diagrams of political harmony, spiritual hierarchy, and noble service within the Doctrine of Medrar.[14]

Endorsed by Diego de Torres Villarroel and introduced with poetic tributes from members of the Academia Poética Matritense, the book encodes a theory of governance through number. Medrano invokes Egyptian and Pythagorean traditions to frame each square as a symbolic structure of delegated rule, aligning mathematics with dynastic continuity and Bourbon pedagogy.[15] Phelipe's mathematical treatise expanded the Doctrine of Medrar, giving new form to delegated rule, structured rise, and the visual grammar of power throughout the centuries.

Dedication to Queen Elisabeth Farnese

The dedication that opens Quadrados mágicos is a pure act of political positioning. Medrano offers his mathematical work to Queen Elisabeth Farnese not as a book, but as a "sacrifice" grounded in sacred geometry and planetary tradition. He invokes the ancients, "those once dedicated... to the Planets," only to reject their "superstitious error," insisting that his offering is rational, Christian, and loyal. The structure of the dedication, like the squares themselves, is ordered, ascending, and centered on a single sovereign axis: the Queen.[1]

The work's dignity, he writes, lies not in its content, but in the royal hand that receives it:

At Your Majesty's feet I imprint the lips of my reverence and raise this small gift I offer. I present these Magic Squares, once dedicated by Egyptians and Pythagoreans to the Planets, theirs founded on superstition and error, mine securing dignity in its object and dedication. They believed such Squares granted protection, an erroneous belief, for the credulous were left exposed to danger. But I, in this sacrifice, extinguish that false superstition and establish a true and constant benefit to the realm, whose superior Planet wards off danger and enriches the glory of Spanish Lords.[1]

Medrano casts Elisabeth as "the superior PLANET," whose aspect ensures protection and noble flourishing. His language becomes a sacred geometry, elevating service into a visible diagram of advancement. In aligning classical form with Bourbon authority, Medrano transforms the magic square into a ceremonial instrument of fidelity.[1]

Solución general y natural de los Quadrados mágicos (1745)

In 1745, Phelipe Medrano authored a manuscript entitled General and Natural Solution to One of the Most Celebrated and Most Difficult Problems of Arithmetic Named Magic Squares, Founded on the Properties That Any Progression Placed in a Square Figure Has, with a Demonstration of the Operations. Significantly longer than his earlier work, it spans over 200 pages of text and tables and presents a distinctly mathematical focus. This complexity may partly account for why, to the best of current knowledge, the manuscript was never published.[2]

Poetic tributes to Phelipe Medrano

Philip was introduced in his Quadrados mágicos with poetic tributes by members of Madrid's literary elite, many of whom were high-ranking nobles, poets, and officials. These texts collectively elevate Phelipe Medrano as a paragon of mathematical virtue, enlightenment learning, and noble service. Collectively, the poetic tributes frame Quadrados mágicos as more than a mathematical treatise. Through imagery drawn from classical philosophy, biblical allegory, and the history of science, Medrano is depicted as a figure who unites erudition, noble lineage, and loyal service to the Crown. The verses consistently contrast ancient superstition with Christian rationality, recasting the magic square from an emblem of idolatry into a symbol of order, governance, and enlightened rule. In this literary context, Medrano’s work is celebrated not only for its technical precision but also as an expression of the Medrano family's enduring Doctrine of Medrar, understood as the advancement of knowledge and the state through disciplined structure and loyal service.[14]

Joseph Cañizares

Among the poetic tributes prefacing the work is a laudatory sonnet by Joseph Cañizares,[16] Theniente de Caballos Corazas, composed in honor of the author and his mathematical achievement:

.jpg)

Socrates immortal, Plato divine; If they ploughed numeric seas, They had a course, for the North they found, Following the Pythagorean path. If the Tarentine of the soul's affections, (and others with him) dealt in numbers, By Nicomachus they found the method, In learned and wandering Arithmos.

Only you (Phelipe), without north or guide, By influences of Sovereign Numen, Brilliant mists, showing the day; The cheerful, vain Egyptian may say, My weak Arithmetical harmony, If it began to medrar, it is because of Medrano.[14]

The connection between medrar and Medrano is not merely etymological; it is also conceptual and programmatic. Classical sources from Antonio de Nebrija to Joan Corominas confirm that the surname Medrano derives from the verb medrar, meaning "to improve," "to advance," or "to prosper."[17][18][19][20][21] The 18th-century poet José de Cañizares made this semantic unity explicit in his tribute to Phelipe Medrano, writing: "If my weak Arithmetic shows any medrar, it is because of Medrano."[14] Here, medrar is not only the act of prospering; it is the function of the Medrano name, elevated into a doctrinal identity. This is precisely what Phelipe Medrano enacts in Quadrados mágicos: a numerical theology of noble advancement.

His magic squares, structured, ascending, and centered, are not idle puzzles but symmetrical manifestations of social and cosmic order. As Àngel Campos-Perales has shown, the Spanish monarchy under the Habsburgs and Bourbons relied on Medrar to curate visual grammars, including chapels, funerary architecture, heraldry, and ceremonial emblems, to create a symbolic language that legitimized delegated power and kingship within the visual field of court society.[22]

Quadrados mágicos fulfills this same function in mathematical form. Through calibrated order and recursive harmony, Medrano’s squares become a visual geometry of Medrar: noble advancement through ordered legitimacy made intelligible through number. They inscribe, in mathematical structure, what the name Medrano etymologically and doctrinally signifies: improvement, legitimacy, and structured ascent. In this way, each magic square becomes not only a solution but a visible step in the Medrano Doctrine of Medrar.[23]

Ignacio de Loyola y Oyanguren, 2nd Marqués de la Olmeda

The Elogio by Ignacio de Loyola y Oyanguren, 2nd Marqués de la Olmeda and dedicated to Phelipe Medrano in the Quadrados mágicos (1744) declares:

The Egyptians invented magic squares, And placed their deities in them, As though divinity resided In whatever had quantity, For the Supreme Deity Knows no bounds, nor permits summation, Their delirium ever shifting, A new literary labyrinth. But today your noble name Amazes the entire world, Lifting from such blind confusion The undeniable being of truths. I have gladly examined The work you’ve shared with me; In its progressions, You’ve refined the combinations So the world may see, If one studies with care, How distance conquered Turns ignorance into radiance. Your tested problems Leave my concerns so fully satisfied, That any studious mind To which they are applied, wise and attentive, Will find you have reached such depth of understanding, That, once acquired, your knowledge becomes inherited.

Since your father, in brief, Granted you the improvement of third and fifth, Your father, whose glory Was a living Archive of History, And in affairs of State, A Caliodorus of the world, celebrated far and wide, What wonder, then, if my rough wit Should stand in awe of a branch sprung from such a trunk? Our friendship, in short, is not of recent days, For it holds its proper place before the lady.

I’ve always known Your playful genius in study, And in your early green seasons, Like a rational bee you gathered blossoms So that those flowers would yield fruit. Mathematics is what you descend from, A sea of faculties, which, when grasped, Even in narrow chambers, Reduce to number and to measure. There is nothing in this life That cannot be reduced to number, Even human fate Finds its final unity in death. That beautiful planet, Which follows its luminous course, In the zenith of its rays, Turns its light into a foam-topped grave. The rose, which in various views Is seen as the living water of attentions, When its bud is threatened, Finds that from one unit alone it grows, And breaking the bud’s scarlet shell, Expands into countless forms. The poor little spring, Brief in its course, yet marvelous, When it becomes a deep arroyo, Offers a crystal torrent, And in time, as it animates its being, Its liquid flow multiplies.

Thus it is seen in light, in crimson, and in foam, The multiplication, the line, and the smoke. Books of the clearest minds Often carry more contradiction, But your book, in superior fortune, Suffers neither flaw nor failing, For to criticize it, One must first comprehend it. So much consequence You place in demonstration, That what you prove Silences the Babel of dispute, For in mathematics, Only "ergo" makes the proof. You are today a new Ganymede, Grasping Archimedes' spheres, Drawing from their motions New problems from Euclid’s torrent. And as Isidore once said With truth on his lips and a golden pen, That to join the whole with its parts Is the science of sciences and art of the arts, Let my crude tongue cease its applause, For here, silence itself is eloquence.[14]

The tribute to Phelipe Medrano, composed by Ignacio de Loyola y Oyanguren, 2nd Marqués de la Olmeda is a doctrinal witness, a compressed theology of number, authority, and lineage that situates Medrano's work within both the Christian tradition and the universal Doctrine of Medrar. Loyola begins by recalling that the Egyptians "invented magic squares" and placed their deities within them, as though divinity could be reduced to quantity. Against this, he asserts that the "Supreme Deity knows no bounds, nor permits summation." The elogio echoes the Medrano doctrine: number is not itself divine, but a sign of divine order. Medrano is praised as the one who purifies mathematics from superstition and re-anchors it in theology and law.[1]

.jpg)

The tribute contrasts the "delirium" and "labyrinth" of pagan systems with the clarity that comes "today" through the Medrano name. To say "your noble name amazes the entire world" is not presented as flattery alone. It positions Medrano identity, rooted in medrar meaning to rise and to advance, as a public emblem that transforms confusion into truth. The name itself is presented as a doctrinal sign of order.[1]

In describing Medrano's "progressions" and "combinations," Loyola moves from technical vocabulary to moral theology. Mathematical method disciplines not only the intellect but also desire, converting ignorance into radiance. The problems Medrano sets are "tested," and the "inheritance" of his knowledge is emphasized. His mathematics is portrayed as transmissible, forming future generations. Nobility is presented here as pedagogical as much as genealogical. The image of the "rational bee" gathering blossoms underscores this point, presenting Medrano's learning as ordered play that yields lasting fruit.[1]

Specifically, In the Elogio, the 2nd Marquess of La Olmeda described Phelipe Medrano as a "rational bee," gathering from varied flowers to form a disciplined and ordered sweetness. The metaphor of the bee had already appeared in the Medrano tradition: in his República Mista, Tomás Fernández de Medrano compared political unity to the natural order of bees, "in whom one queen rules; as in the flock one shepherd; in the world one God; and in the kingdom one prince."[3] Read together, these images illustrate how Spanish society employed the bee as a recurring symbol, at once of intellectual formation in the Elogio and of political and theological order in Tomás's treatise.[3] By drawing on the same image, Ignacio de Loyola's tribute connected Phelipe Medrano's mathematical treatise and his surname to the legitimacy and continuity of the established doctrine that the Medrano family had been cultivating for centuries.[1]

Loyola further insists that Phelipe Medrano's book suffers "neither flaw nor failing" and that his demonstrations silence the "Babel of dispute." Proof rather than patronage confers legitimacy. In the same way that governance depends on demonstrable justice, mathematics depends on the necessity of demonstration. Medrano is described as a "new Ganymede" grasping Archimedes' spheres, a metaphor for noble ascent joined to service of sovereign authority. Loyola concludes by invoking Isidore of Seville's maxim that wisdom joins the whole with its parts, suggesting that Medrano's magic squares achieve this union by binding throne and subject, unit and sum, universal and particular.[1]

The elogio presents Phelipe Medrano as reformer of number and demonstrator of the doctrine of Medrar. It frames his name as a sign of order revealed to the world, lifting mathematics from superstition into truth. The amazement of the world Loyola describes is not mere admiration but recognition of a principle inscribed in creation: that true nobility lies in transmitting order from the One to the many, and from the many back to the One.[1]

Joaquín de Aguirre

His friend Joaquín de Aguirre wrote the following "on the occasion of publishing the Treatise" of the Magic Squares:

Darkness teaches, which exhales vice In clumsy fumes that nourish error, All that is obscure is driven away by Light, And sacrilege transforms into Sacrifice. An irrational reef, where the Egyptian Treads misguided steps in bloodied ways, Now becomes a heroic blazon, no longer a shame, If frenzy slumbers, let judgment rise. That which was once impossible is now conquered, That which was mute now speaks and is explained: That error, converted into truth. Sacrilege is now a consecrated emblem, It spreads nobility to the public, The prodigious name of a Crusader.[15]

Aguirre wrote a second sonnet dedicated to Medrano:

If faith could secure the noble effort Of that other Philosopher who once claimed That one soul passed through many bodies, Then yours, Medrano, stands above his. Madness it seemed, or error, or a foolish dream, Yet the world itself praises you, Though some denied it with lesser assent, Their judgment diminished by their own pride. Indeed, Pythagoras said the soul Could not remain in a single form, But the soul that animated you wins the crown. So let them discuss, invent, write, teach, dispute, The greatest minds now stand aside, Asking: was that soul his, or is yours the better?[14]

Miguel de Villa-Fuerte

Among the poetic tributes prefacing the work is a sonnet by Don Miguel de Villa-Fuerte, lawyer of the Royal Councils, composed in praise of the author and his learned achievement:

By what rule, instruction, or teaching Humbly I ask, have you uncovered That uncultivated path, long smothered, Which thought alone deemed unapproaching? If in nine Problems you staked your aim To discern and resolve where lofty heights dwell, The subtle art you studied well, Revealing clear your Arguments’ flame. Ah, do not answer how to understand you; Jealousy more than ignorance would know you, Let the Egyptians themselves bow down in awe. Nearly impossible to imitate you, None may presume to grasp what you do, In the difficult, you are the law.[14]

Francisco de Quadros

Don Francisco de Quadros, Knight of the Order of Santiago, offers a poetic tribute titled "Heroic Romance" applauding the tireless study of Phelipe Medrano and his accomplishment in composing the Magic Squares once devised by the Egyptians:

If the Egyptians, with errant trace, Worshipped fabled deities' delight, And in the unfathomable gulf of guile, Sought to fix their foot in glory’s place, Tearing bronze in solemn rite, Their fraud hid under hardness bright, Numbers they privileged with divine right, Though no Numen they adored with grace. Superstitious simulacra made Votive smoke serve as torchlight’s aid, Letting their madness burn once more. And in their study, void of guide, They left no trace or text behind, So none might follow, none explore. But what applause now may be born, Lesser (O great MEDRANO) than your scorn, If daring measured the impossible's form? Your golden pen has sealed their mouths forlorn. Magic, they called your noble aims, Yet only fools would make such claims, For in their error, none believed A man such glory could achieve. Arithmetic, in you its purest height, Crowns you with its diadem bright, And from the secret path of numbers’ might, You pass still further when it takes flight. The strange Problems your labor posed Shamed curiosity’s boastful prose, For insight prefigured all you chose, Before the page your logic froze.[14]

Legacy

The Medrano name and doctrine had been formally articulated in the República Mista and later codified into sacred numbers by Phelipe Medrano.[3][24] The poetic tributes accompanying Quadrados mágicos present Phelipe Medrano not only as a mathematician but as a successor to this family tradition of loyalty expressed through structured and symbolic order. Taken together, the tributes situate Quadrados mágicos within this lineage, portraying the work as both a technical achievement in mathematics and a continuation of the Medrano family’s role in uniting scholarship, governance, and noble duty.[25]

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r Medrano, Phelipe de (1744). Quadrados mágicos (in Spanish). Madrid: Imprenta de Antonio Marín. Retrieved 2025-05-08.

- ^ a b Digital Bulletin of the Aragonese Society "Pedro Sánchez Ciruelo" of Mathematics Teachers. http://sapm.es/EntornoAbierto/EntornoAbierto-num49.pdf

- ^ a b c d Medrano, Juan Fernandez de (1602). República Mista (in Spanish). Impr. Real.

- ^ a b Escalada, Carles de (2024-03-12). "Caballeros de la Orden de Santiago en Serón, Soria". Knights of the Order of Santiago in Serena, Spain.

- ^ Medrano, García de (1605). Copilacion de las leyes capitulares de la Orden de la Caualleria de Santiago del Espada (in Spanish). Valladolid: Luis Sánchez.

- ^ Proyectos, HI Iberia Ingeniería y. "Historia Hispánica". historia-hispanica.rah.es (in Spanish). Retrieved 2025-08-16.

- ^ "Medrano family heraldry genealogy Coat of arms Medrano". Heraldrys Institute of Rome. Retrieved 2025-08-16.

- ^ de Loyola, Fernando. "Historia Hispánica". historia-hispanica.rah.es (in Spanish). Retrieved 2025-08-16.

- ^ The Elogio by the Marqués de la Olmeda, Quadrados Magicos, 1744.

- ^ de Loyola, Ignacio. "Historia Hispánica". historia-hispanica.rah.es (in Spanish). Retrieved 2025-08-16.

- ^ Relación de Sucesos: Manuscrito XVII-8907-58 (PDF) (in Spanish). BIDISO, Universidad de Alicante. Retrieved 2025-05-10.

- ^ "Billete de Antonio de Mendoza a Pedro Medrano, secretario del Consejo de Estado, sobre su nombramiento de residente en Génova con el título de enviado". Portal de Archivos Españoles (PARES) (in Spanish). Archivo General de Simancas, EST,LEG,3636,129. 1672-03-05. Retrieved 2025-05-10.

- ^ "Billete de Lope de los Ríos, presidente del Consejo de Hacienda, a Pedro Medrano, secretario del Consejo de Estado, sobre la ayuda de costa concedida a Antonio de Mendoza". Portal de Archivos Españoles (PARES) (in Spanish). Archivo General de Simancas, EST,LEG,3636,132. 1672-04-08. Retrieved 2025-05-10.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Medrano, Phelipe de (1744). Quadrados mágicos (in Spanish). Madrid: Imprenta de Antonio Marín. Retrieved 2025-05-08.

- ^ a b Díez Borque, José María (2017). "Anotaciones sobre la Academia Poética Matritense del siglo XVIII" (PDF). Dramaturgo y espectáculo en el teatro español del siglo XVIII (in Spanish): 205–225.

- ^ Carlos Ludeña (2023). José de Cañizares (1676–1750): vida y obra de un libretista entre el Barroco y la Ilustración. Oviedo: IFESXVIII / Ediciones Trea, Anejos de Cuadernos de Estudios del Siglo XVIII, ACESXVIII 12, pp. 1–173. doi:10.17811/acesxviii.12.2023.1-173. ResearchGate. Accessed 18 May 2025. (in Spanish)

- ^ Antonio de Nebrija, Diccionario Latino-Español, 1492.

- ^ Pineda, Pedro (1740). A New Dictionary, Spanish and English... London. p. 348.

- ^ Pedro Felipe Monlau, Diccionario etimológico de la lengua castellana, Madrid, 1856, p. 329.

- ^ Joan Corominas, Diccionario Crítico Etimológico de la Lengua Castellana, Vol. IV, Editorial Gredos, 1980, p. 19.

- ^ Ramón Menéndez Pidal, cited in Orígenes del español, Madrid, 1926.

- ^ Campos-Perales, Àngel (2024). "Los validos valencianos del valido: arte y legitimación social en tiempos del Duque de Lerma (1599–1625)". Espacio, Tiempo y Forma. Serie VII: Historia del Arte (in Spanish). 12. Madrid: UNED: 275–296. doi:10.5944/etfvii.12.2024.38583. Retrieved 2025-05-08.

- ^ Nebrija, Diccionario Latino-Español, 1492; Pineda, New Dictionary, 1740; Corominas, Diccionario Crítico Etimológico, vol. IV, 1980.

- ^ Diego, Medrano Ceniceros; Coloma y Escolano, Pedro. "Heroic and Flying Fame of Luis Méndez de Haro". Heroic and Flying Fame... Archived from the original on 2024-09-01.

- ^ Fernández, Myriam Ferreira (2018-11-29). "La biblioteca del arquitecto Francisco Alejo de Aranguren (1739-1785)". BSAA arte (in Spanish) (84). ISSN 2530-6359. Archived from the original on 2022-07-17.

- Medrano, Phelipe de (1744). Quadrados mágicos (in Spanish). Madrid: Imprenta de Antonio Marín. Retrieved 2025-05-08.

- Medrano, Phelipe de (1744). Quadrados mágicos (Biblioteca Nacional de España) (in Spanish). Madrid: Biblioteca Nacional de España.

- Oller Marcén, Antonio M. "Felipe Medrano y sus cuadrados mágicos". FUNES. Repositorio de Documentos (in Spanish). Universidad de los Andes. Retrieved 2025-05-09.

- Díez Borque, José María (2017). "Anotaciones sobre la Academia Poética Matritense del siglo XVIII" (PDF). Dramaturgo y espectáculo en el teatro español del siglo XVIII (in Spanish): 205–225.

- Mendoza Caamaño Sotomayor, Antonio Domingo de (1672-03-05). "Billete de Antonio de Mendoza a Pedro Medrano, secretario del Consejo de Estado, sobre su nombramiento de residente en Génova con el título de enviado". Archivo General de Simancas (in Spanish). Madrid. Retrieved 2025-05-10.

- Relación de Sucesos: Manuscrito XVII-8907-58 (PDF) (in Spanish). BIDISO, Universidad de Alicante. Retrieved 2025-05-10.

- Ludeña, Carlos (2023). José de Cañizares (1676–1750): vida y obra de un libretista entre el Barroco y la Ilustración. Anejos de Cuadernos de Estudios del Siglo XVIII, ACESXVIII 12 (in Spanish). Oviedo: IFESXVIII / Ediciones Trea. pp. 1–173. doi:10.17811/acesxviii.12.2023.1-173. Retrieved 2025-05-18.