Petrovci, Croatia

Petrovci, Croatia

| |

|---|---|

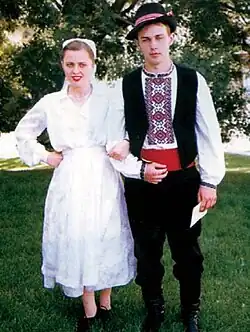

Local villagers of Petrovci | |

| |

Petrovci  Petrovci  Petrovci | |

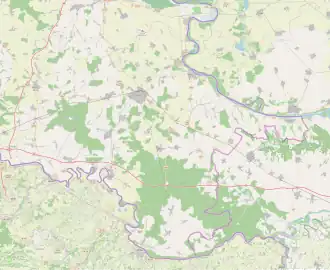

| Coordinates: 45°17′N 18°57′E / 45.283°N 18.950°E | |

| Country | Croatia |

| Region | Syrmia (Podunavlje) |

| County | |

| Municipality | Bogdanovci |

| Area | |

• Total | 22.1 km2 (8.5 sq mi) |

| Population (2021)[3] | |

• Total | 643 |

| • Density | 29/km2 (75/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

Petrovci (Pannonian Rusyn: Петровци,[4] Ukrainian: Петрівці, Serbian Cyrillic: Петровци) is a village in eastern Croatia, in the municipality of Bogdanovci. According to the 2011 census, it had a population of 864. The majority of residents are ethnic Rusyns.

The Ruthenians originally came from Hornjica, eastern Slovakia to the Ruski Krstur around 1750, today's Serbia, and between 1830 and 1880 they came to Croatia. The Ruthenian Greek Catholic parish in Petrovci was founded in 1836 and had 1,350 believers. [5]

History

During World War II in Yugoslavia, Petrovci became one of the centers of anti-fascist resistance in the Vukovar region. In the autumn of 1942, the second local People's Liberation Committee was founded in the village, initiated by Živojin Jocić from Pačetin, then secretary of the Vukovar District Committee of the Communist Party of Croatia.[6] Key local organizers included Joakim Edelinski, Vukašin Veličković and Proka Vukosavljević along with other residents of the village.[6]

The first group of volunteers from the village joined the Yugoslav Partisan movement in the summer of 1943.[6] Throughout the war, Petrovci maintained an active underground structure, including a Communist Party cell, the Local People's Liberation Committee, the League of Socialist Youth of Yugoslavia, and the Women's Antifascist Front.[6]

Among the most prominent local resistance fighters was Joakim Edelinski (1907–1944), born into a poor family and employed as a seasonal laborer.[6] As one of the earliest organizers of the National Liberation Movement in Petrovci, Edelinski played a central role in forming the first NOO in the village.[6] Due to increasing exposure, he left for the front lines together with a group of future Partisans and his 15-year-old daughter Pavlina.[6] He was later assigned to the 16th Youth Brigade "Joža Vlahović" and killed in combat near Krašić in March 1944.[6] Another key figure was Milenko Apić (1922–1944), a former student who served as the SKOJ secretary in the village.[6] He later joined the district leadership of the United Antifascist Youth of Croatia and helped organize resistance efforts in western parts of the Vukovar district.[6] He was killed in Bršadin on May 30, 1944.[6]

In total, 34 residents of Petrovci died as soldiers of the People's Liberation Army, while 12 civilians were killed as victims of fascist terror.[6] One of the gravest incidents occurred on December 22, 1944, when eight local activists were executed following the information given by a Sudeten German soldier who had gathered intelligence in the village.[6]

Petrovci was liberated on April 13, 1945, by the 4th Brigade of the 21st Serbian Division.[6]

In the postwar years, several memorials were erected to honour the village’s resistance.[6] In 1975, a memorial fountain was built to mark the 30th anniversary of both the liberation of Petrovci and the execution of local patriots.[6] On May 23, 1982, a monument dedicated to the eight executed activists was unveiled in the yard of the Serbian Orthodox Church.[6] In addition, several commemorative plaques throughout the village continue to preserve the memory of those who gave their lives in the struggle against fascism.[6]

Local Serbian Orthodox Church was damaged in 1991 during the Croatian War of Independence but was subsequently reconstructed in 1992 when the village was incorporated into SAO Eastern Slavonia, Baranja and Western Syrmia.[7]

See also

References

- ^ Government of Croatia (October 2013). "Peto izvješće Republike Hrvatske o primjeni Europske povelje o regionalnim ili manjinskim jezicima" (PDF) (in Croatian). Council of Europe. p. 34. Retrieved 29 November 2016.

- ^ Register of spatial units of the State Geodetic Administration of the Republic of Croatia. Wikidata Q119585703.

- ^ "Population by Age and Sex, by Settlements" (xlsx). Census of Population, Households and Dwellings in 2021. Zagreb: Croatian Bureau of Statistics. 2022.

- ^ "Minority names in Croatia:Registar Geografskih Imena Nacionalnih Manjina Republike Hrvatske" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-10-29. Retrieved 2013-03-08.

- ^ "Rusini u Hrvatskoj – Hrvatska internetska enciklopedija". enciklopedija.cc. Retrieved 2022-10-02.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r Brana Majski (1985). Spomenici revolucije Vukovar [Monuments of the Revolution Vukovar] (in Serbo-Croatian). Skupština općine Vukovar & Općinski odbor saveza udruženja boraca narodnooslobodilačkog rata & Gradski muzej Vukovar. pp. 92–99.

- ^ Filip Škiljan (2025). "Stradanje hramova Srpske pravoslavne crkve u ratu u Hrvatskoj 1991. - 1995. i poraću (1996. - 1997.)" [Destruction of Serb orthodox churches in the war in Croatia 1991 - 1995 and the immediate post-war period (1996 - 1997)]. Tragovi: Journal for Serbian and Croatian Topics (in Croatian). 8 (1): 7–46.