Pedro González de Medrano

Pedro González de Medrano | |

|---|---|

| Nobleman and Knight of Navarre | |

.jpg) Pedro González de Medrano wears a close helmet while holding the Medrano standard at the Battle of Las Navas de Tolosa in 1212. Detail from the painting by Francisco de Paula Van Halen. | |

| Active | fl. 1212 |

| Full name | Pedro González de Medrano |

| Other titles | Knight of the royal retinue of King Sancho VII of Navarre |

| Born | Pedro González de Medrano Late 12th century Igúzquiza, Kingdom of Navarre |

| Died | 13th century Kingdom of Navarre |

| Family | House of Medrano |

| Children | Íñigo Vélaz de Medrano |

| Occupation | Knight, nobleman |

| Memorials | Medrano Street in Navas de Tolosa (Jaén) |

| Notes | |

| He was the great-grandfather of Juan Martínez de Medrano, regent of Navarre (1328–1329). | |

Pedro González de Medrano (fl. 1212) was a Navarrese nobleman who rode in the royal retinue of King Sancho VII of Navarre during the battle of Las Navas de Tolosa, where he carried the Medrano family standard. He participated in one of the most decisive campaigns of the reconquista, continuing a noble lineage that would later include crusaders, feudal lords, and regents of Navarre.[1] His arms, along with mentions in official chronicles and depiction in historical artworks, attest to the Medrano family's role in shaping the medieval Christian world of the Iberian Peninsula.

Background

Pedro González de Medrano belongs to the Medrano lineage known in Navarre as the lords of Igúzquiza. His family later held feudal land in Sartaguda, Fontellas, Monteagudo, Learza, Azpa, etc. He was born most likely at the palace of Vélaz de Medrano, and his family remained closely aligned with the kings of Navarre, appearing alongside them in some of the most defining moments of Navarrese history.[2] The Medrano family is a very ancient House of noble origin.[3][4]

As noted by Iñaki Garrido Yerobi in Las Mercedes Nobiliarias del Reino de Navarra, the Medrano family constituted a deeply entrenched branch of the titled nobility in the Kingdom of Navarre. Descendants of Pedro González de Medrano, particularly the lords of Igúzquiza, Learza, Azpa, and Arróniz, intermarried with the royal House of Évreux, acquiring maternal lineage from Kings Philip III, Charles II, and Enrique I of Navarre.[5]

Pedro's generation marked the consolidation of the Medrano family's noble standing in the Kingdom of Navarre. His role at the Battle of Las Navas de Tolosa in 1212 reflected the culmination of more than a century of ascent within the Navarrese aristocracy. This legacy would continue through his descendants.[6]

.png)

Pedro's life combined military service and heraldic tradition.[3] His coat of arms, bearing a red cross fleury on a gules field, became a lasting symbol of the family's martial heritage.[4] In 1276, his grandson Juan Martínez de Medrano, lord of Sartaguda, Alcaide of the castle of Viana, used the symbol in a heraldic scalloped seal measuring 50mm,[7][8] and a second seal in 1279, featured the same scalloped seal, 45mm in size.[9][10][11] During the time of Pedro's great-grandson, for eleven months, this seal became the official symbol through which the Kingdom of Navarre was represented during Juan Martinez de Medrano y Aibar's regency in 1328 during an Interregnum.[12]

Heir

Pedro was the father of Íñigo Vélaz de Medrano. His son, Íñigo Vélaz de Medrano, would later participate in the Eighth Crusade under Theobald II of Navarre and Louis IX of France. The seal of this knight Íñigo Vélaz de Medrano is preserved in several documents, including the one containing a donation from the king to the monastery of Leyre (1268).[13]

The Basque Nobility marched to the Crusade with their King Theobald II of Navarre, and under the supreme direction of the Holy King Louis IX of France. Íñigo Vélaz de Medrano was called and chosen by the King.[14] Íñigo Vélaz de Medrano, and many other noblemen of no less quality answered the call.[14]

Grandson

Íñigo was the father of Juan Martinez de Medrano, Lord of Sartaguda, ricohombre of Navarre.[14] In 1260 AD, Pedro's grandson Juan Martínez de Medrano was given the castle of Viana by King Theobald II of Navarre. His grandson was designated as the person responsible for defending the town and villages in that area on the border of Navarra with Castilla.[15]

This defensive duty paralleled an earlier responsibility of the family: shortly after the founding of the cities in the 11th century, the castles of Vélaz de Medrano and Monjardín had been constructed under the command of the Vélaz de Medrano family to safeguard the key routes leading from Álava and Logroño.[2]

Pedro's grandson, Juan Martínez de Medrano, described as "a valiant captain," perished in the mountains of Beotriva during the ill-fated expedition of 1322, led by Ponce de Morentana, a French knight and viceroy of Navarre in Guipúzcoa, who commanded an army of 60,000 men.[6][16]

Descendants

Pedro's great-grandson, Juan Martínez de Medrano, baron and lord of Sartaguda, ricohombre of Navarre, alcaide of several castles, a judge in the Navarrese Cortes, and lord of Arroniz and of Villatuerta, served as regent of the Kingdom of Navarre during the 1328 interregnum.[12]

Pedro's great-great-great-grandson Juan Vélaz de Medrano became the royal chamberlain to both Charles III of Navarre and John II of Aragon. Pedro's direct descendants, including Juan Vélaz de Medrano y Mauleon, Baron of Igúzquiza; Alonso Vélaz de Medrano Navarra, Viscount of Azpa; and Pedro Antonio de Medrano y Albelda, regent of the kingdom of Navarre, are descendants of Charles III of Navarre and the Monarchs of Navarre.[17]

The Medrano family held the Marquessate of Fontellas, the Marquessate of Tabuérniga de Vélazar, the Marquessate of Vessolla, the Barony of Mahave, the Marquessate of Espinal, the County of Torrubia, and many other titles.

Family

Pedro González de Medrano belonged to a noble house of ancient origin, renowned across centuries and regions. Chroniclers and historians have attributed to his lineage a legacy of distinction, praised for its antiquity, martial excellence, chivalric virtue, and the enduring abundance of its magnanimous and illustrious members.[3]

233 years prior to the battle of Las Navas de Tolosa, Pedro's progenitor, Andrés Vélaz de Medrano, a Moorish prince from the Umayyad Caliphate of Córdoba, converted to Christianity, an act that solidified the family's adoption of the Ave Maria motto and the goshawk emblem. These symbols became internationally recognized across the house's many branches, including the Barons of Igúzquiza, Counts of Torrubia, Marquesses of Fontellas, and others.[18][19][4][20]

Lords from the palace of Velaz de Medrano also depicted a gules field with a silver trefoil cross on their coat of arms. The border featured the Ave Maria motto.[21]

By the 12th century, the House of Medrano had firmly maintained their influence among the high nobility of the Kingdom of Navarre. Pedro González de Medrano represented the main Navarrese branch closely aligned with the royal court of Pamplona. His position in the royal retinue of King Sancho VII of Navarre reflects the elevated status the family had achieved through military loyalty and ancestral service.[5]

During this period, separate but related branches of the Medrano family held lordships in La Rioja, notably the lordships of Agoncillo and Fuenmayor, where they became vassals of the Castilian crown. Despite their differing political allegiances, both the Navarrese and Castilian Medranos shared a common ancestry and upheld similar traditions of noble service, including administrative, clerical, and military duties, as well as ecclesiastical patronage to the Order of Saint John and Saint Francis of Assisi.[22]

Relatives

Pedro's relatives, originating from Soria and Viana, and linked to the castles of San Gregorio and Barajas in Madrid, initially settled in Ciudad Real.[23] There, members of the Medrano family participated in the Reconquest of Alarcos in 1212 alongside Alfonso VIII of Castile at the Battle of Las Navas de Tolosa, and later served as lords of the Torre de la Galiana.[24] It was during this period of growing ecclesiastical and territorial influence that Pedro González de Medrano emerged as one of the family's most distinguished knights.

Medieval patronage in Spain

Ecclesiastical patronage, largely overlooked in historiography, was among the greatest demonstrations of supremacy and distinction available to the nobility at the time. Its appropriation by others in later centuries was far less common.[25]

Saint Francis of Assisi and the Medrano family

.jpg)

One year before the battle of Las Navas de Tolosa, Pedro's family became linked to a miracle that took place during his lifetime. According to Fray Domingo Hernáez de Torres in his Primera parte de la Crónica franciscana de la Provincia de Burgos (1772), the first Franciscan convent in Spain was founded on land donated by the House of Medrano in 1211.[26]

In 1211, Saint Francis of Assisi was traveling through the region of La Rioja and came to the Castle of Aguas Mansas in Agoncillo, then held by a lord of the Medrano family. A young Medrano boy and heir was gravely ill with an incurable condition, and Saint Francis visited the fortress and is said to have miraculously healed the child, securing the Medrano lineage in the lordship of Agoncillo.[27]

In gratitude, the Medrano family donated a tower and land near the Ebro River to Saint Francis of Assisi himself, allowing the saint to establish the first Franciscan presence on Iberian soil, in the city of Logroño.[28]

This foundational episode marked the beginning of the Medrano family's enduring patronage of the Franciscan Order, a spiritual alliance that would span centuries. By the late 14th century, this devotion culminated in the establishment of a perpetual chaplaincy by Diego López de Medrano, Lord of Agoncillo, royal steward and ambassador of the king of Castile, in the main chapel of the Monastery of San Francisco in Logroño. The patronage rights remained with the Medrano family until the 19th century.[29][27]

For Pedro González de Medrano, living during the time of the miracle, this sacred event and its legacy would have further affirmed the family's dual identity as both noble warriors in service of the king and patrons of religious orders. The Medrano coat of arms, still carved in stone above the gate of Aguas Mansas, stands as a testament to both their noble status and enduring spiritual alliance.[30]

The Medrano family's patronage to the Order of St. John

While Pedro González de Medrano represented the main Navarrese branch of the Medrano family, based in Igúzquiza and Sartaguda, loyal to the Crown of Navarre, a related branch had already become influential in La Rioja by the 12th century. María Ramírez de Medrano, a noblewoman, held the title of Lady of Fuenmayor in the 12th century within the Kingdom of Castile.[31] The Medrano family, recognized as the principal noble lineage of Fuenmayor in La Rioja, held the lordship of the town through inheritance from María Ramírez de Medrano for generations.[27]

María was not only a landholder but a patron of the Order of Saint John of Acre in 1185, founding a convent, commandery and hospital affiliated with the Knights Hospitaller in Navarrete, close to the Camino de Santiago.[32] The towns of Baztán, where María Ramírez de Medrano's husband was from, along with Entrena, Medrano, and Fuenmayor, were all part of the jurisdiction or domain of María's hospital of San Juan de Acre in Navarrete[32] Her actions reflect the family's early tradition of ecclesiastical patronage, which paralleled the family's own support of the Franciscans in Agoncillo.[33] Her son Martín de Baztán y Medrano (died 27 July 1201) was ordained a bishop of the Diocese of Osma in Soria in 1188.[33][34]

Archaeological investigations of the palace of Vélaz de Medrano uncovered remnants of a medieval pilgrim hospital supplied by a water conduit attributed to Pedro's family in their lordship of Igúzquiza. The site, located on former lands of the Hospitaller Brothers of St. John of Jerusalem, reflects the longstanding association between multiple branches of the Medrano lineage and the Order of St. John.[2]

Portrait

.jpg)

Pedro González de Medrano, depicted wearing a close helmet and bearing the Medrano family heraldic flag, appears just behind the front lines in The Battle of Las Navas de Tolosa (1212) by Francisco de Paula Van Halen. His white flag, marked by a shield with a distinctive red cross fleury on a gules field, sets him apart from the surrounding orders and royal insignia, clearly identifying him as the Medrano knight serving in the personal retinue of King Sancho VII of Navarre.[6]

His escutcheon was included in Francisco de Paula Van Halen's monumental painting "Battle of Las Navas de Tolosa," where the Medrano standard is prominently visible among the standards of the knights of Calatrava, Santiago, and other royal orders. The painting is currently housed in the Senate Palace of Spain, visually preserving Pedro's role in the battle for posterity.[35]

.svg.png)

At the battle he is recorded as bearing arms described in several sources as a gules shield with an argent cross fleury, a design associated with the cross of the Order of Calatrava.[6][27]

According to Piferrer in 1955, this particular coat of arms from the House of Medrano featuring an argent fleur-de-lis cross of Calatrava on a blood-red field, symbolized their ancient lineage through its straightforward design and connection to the battle of Las Navas de Tolosa.[27] In honor of the family's involvement in the battle, there is a street named "Medrano" in Navas de Tolosa, Jaén.[36]

Battle of Las Navas de Tolosa (1212)

Pedro González de Medrano attended the victorious day of Las Navas de Tolosa on 16 July 1212, forming part of the royal retinue that accompanied king Sancho VII of Navarre, and constituted the most significant nobility of the Kingdom of Navarre.[37][6]

At the same time, Martín López de Medrano, a relative of Pedro, served in the royal retinue of King Alfonso VIII of Castile during the battle of Las Navas de Tolosa (1212). He carried a variation of the Medrano standard in Or (gold), later seen again in the Battle of Baeza (1227).[38] Following the battle, Medrano heraldry was enriched:

- With eight or (gold) saltires of Saint Andrew commemorating their participation at the battle of Baeza in 1227.[39]

- Raised at the Battle of Río Salado in 1340.[39]

Before the battle of Las Navas

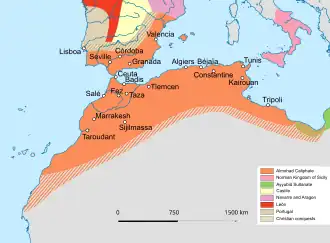

Pedro González de Medrano played a notable role in the famed battle of Las Navas de Tolosa on 16 July 1212, a decisive Christian victory against the Almohad Caliphate. Pedro carried the Medrano family standard and rode in the royal retinue of King Sancho VII of Navarre.[37] Pedro participated in one of the most decisive confrontations of the reconquista, in which Christian kingdoms sought to reclaim the Iberian Peninsula from Muslim rule.[40][41]

The enemy was the Almohad Caliphate, a North African Muslim dynasty that had dominated much of southern Spain.[42] Years earlier, the Almohads had delivered a humiliating defeat to the Castilian forces at Alarcos in 1195, prompting widespread calls for vengeance.[43]

With the support of Pope Innocent III, a formal Crusade was declared,[44] drawing not only Spanish monarchs, Alfonso VIII of Castile and Pedro II of Aragon, but also contingents of French knights and Templars. After initial delays, the Crusading force departed south on June 21, joined by the armies of Aragon, Castile, and Portugal.[43]

Arrival of the Navarrese

Although they captured two Muslim fortresses, the harsh climate and difficult conditions caused the non-Spanish contingents to withdraw. It was then that the forces of Navarre were brought into the campaign.[43] Sancho VII of Navarre arrived with a very strong force of knights.[44]

Although many foreign crusaders eventually withdrew due to harsh conditions, the Navarrese army advanced, committed to the campaign.[45] It was in this context that Pedro González de Medrano, as part of Sancho VII's royal retinue, took up arms, fighting not only for his king and kingdom, but as part of a broader Christian crusade to repel the Almohad threat from the heart of Iberia.[46]

According to the Latin Chronicle of the Kings of Castile, the Christian coalition, composed of the kings of Castile, Aragon, and Navarre, rose at midnight and prepared for battle following Mass and the Eucharist. The troops advanced across rough terrain. Sancho VII commanded one of the rear divisions independently and is described as having arranged his line with such strength and discipline that "whoever passed before his sight would not return."[45]

Battle of Las Navas de Tolosa

Pedro González de Medrano participated in the Battle of Las Navas de Tolosa (1212) as part of the royal retinue of King Sancho VII of Navarre, who played a decisive role in the Christian victory over the Almohad Caliphate.[47] Although relations between the crowns of Castile and Navarre had been strained in the years leading up to the campaign, Sancho ultimately joined the Christian coalition following papal mediation and diplomatic overtures from Castile and Aragon.[48]

According to contemporary sources, including letters from Queen Berenguela and papal legates, Sancho VII of Navarre commanded a distinct wing of the allied army during the final engagement on 16 July 1212. His contingent, which included Pedro González de Medrano, positioned alongside three conrois of Castilian troops, launched a pivotal assault on the fortified camp of the Almohad Caliph Muhammad al-Nasir (known as Miramolín in Christian chronicles). This encampment was defended by the caliph's elite African guards, whose chained fortifications gave rise to later symbolic associations with the chains in the Navarrese and Igúzquiza coat of arms.[48]

At a critical moment in the battle, when portions of the Christian army began to falter and retreat, the Navarrese forces, alongside Castilian and Aragonese units, pushed through the enemy's center. King Sancho's charge breached the caliph's defensive lines, leading to the collapse of Almohad resistance and the caliph's flight from the battlefield. Chroniclers emphasize the role of king Sancho's height and martial presence in rallying troops during this assault.[48]

Pedro González de Medrano is believed to have taken part in this charge, serving among the elite Navarrese knights who penetrated the heart of the Almohad position. His presence at Las Navas de Tolosa places Pedro González de Medrano at the center of one of the most significant victories of the Reconquista and underscores the longstanding martial tradition of the Medrano family in service of the Kingdom of Navarre.[27]

Victory

The tide turned definitively when the king of Morocco, the Miramolín, fled the field. In the final phase of the battle, Sancho VII led the breakthrough of the enemy's last line of defense, a wall of ten thousand chained African slave-soldiers surrounding the Miramolín's tent. Pedro González de Medrano is believed to have participated in this critical assault, fighting under Sancho's command. This breach of the Almohad stronghold marked the collapse of the caliph's forces and secured Christian victory.[45]

The King of Morocco, who had been seated at the center of his formation and surrounded by his chosen warriors, rose, mounted a horse or mare, and fled the battlefield. His troops were quickly overwhelmed, and many were killed. The Moorish camp, once filled with tents and soldiers, was left strewn with the dead. Those who managed to escape fled into the surrounding mountains in disarray, without leadership, and were killed wherever they were encountered.[45]

Following the battle, the allied forces advanced into Muslim-held territory, capturing key fortifications including Vilches, Baños, Tolosa, and Ferral, and besieging Úbeda. According to the chronicle, Sancho VII was later restored certain castles previously seized in Navarre, in recognition of his contribution. The campaign was hailed as a triumph across Christendom.[45] The chains and emerald on the coat of arms of Navarre commemorate the triumph at this battle, symbolizing both the Kingdom of Navarre's victory and the broader success of the Christian crusade.[49]

The full consequences of the Muslim defeat only became evident after 1233, when internal dynastic conflicts led to the collapse of the Almohad empire. Without a unified leadership, Muslim control over Spain quickly crumbled in the face of advancing Christian forces during the reconquest.[43]

Coat of arms of Igúzquiza and the battle of Las Navas de Tolosa

.svg.png)

For their direct participation, the historical lordship and present municipality of Igúzquiza, once held in perpetuity by the House of Medrano from the palace of Vélaz de Medrano, prominently displays the golden chains of the Almohads on its coat of arms, a direct allusion to the Christian victory at the Battle of Las Navas de Tolosa (1212), in which Pedro González de Medrano fought under King Sancho VII of Navarre. These chains, originally encircling the tent of the Miramolín, became the enduring symbol of Navarre's triumph and were later incorporated into both the royal arms of the kingdom, and on the coat of arms of the lordship of Igúzquiza, under the House of Medrano for centuries.

On the Igúzquiza arms, the chains are rendered without the central emerald, signaling ancestral participation in the battle without claiming sovereign status. Crowning the coat of arms is a distinctive hybrid coronet, blending the pearl-tipped points of a marquessate with the structure of a ducal coronet, symbolizing the hereditary union of the Marquessate of Vessolla with the later Duchy of Elío under the House of Elio y Vélaz de Medrano.

References

- ^ Moret: Anales de Nabarra, (ano. 1328)

- ^ a b c IZAGIRRE, ANDER (2007-08-25). "La arqueología campesina de Ramón". El Diario Vasco (in Spanish). Retrieved 2025-07-26.

- ^ a b c "Medrano family heraldry genealogy Coat of arms Medrano". Heraldrys Institute of Rome. Retrieved 2025-07-26.

- ^ a b c "MEDRANO - Auñamendi Eusko Entziklopedia". aunamendi.eusko-ikaskuntza.eus. Retrieved 2025-07-26.

- ^ a b Garrido Yerobi, Iñaki. Las mercedes nobiliarias del Reino de Navarra: siglos XV–XIX. Pamplona: Gobierno de Navarra, Departamento de Cultura y Turismo–Institución Príncipe de Viana, 2005. Annex: Genealogical Table. https://ramhg.es/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/garrido_mercedes_nobiliarias_reino_navarra_anexo_cuadro_genealogico.pdf

- ^ a b c d e Piferrer, Francisco (1858). Nobiliario de los reinos y señorios de España (revisado por A. Rujula y Busel) (in Spanish).

- ^ Archive of the Empire, reference J614, number 264

- ^ "moulage : Douet d'Arcq 11421". Sigilla (in French). Retrieved 2025-07-26.

- ^ Archive of the Empire, J613, number 16

- ^ d'Arcq, Louis-Claude Douet (1868). Archives de l'Empire: Inventaires et documents. Collection des sceaux. Fin de la Premiere Partie - Seconde Partie. Tome 3 (in French).

- ^ "sceau_type : Juan Martinez de Medrano - sceau - 1279". Sigilla (in French). Retrieved 2025-07-26.

- ^ a b Proyectos, HI Iberia Ingeniería y. "Juan Martínez de Medrano". historia-hispanica.rah.es (in Spanish). Retrieved 2025-07-26.

- ^ Archivo de los Bajos Pirineos. – Leire

- ^ a b c Argamasilla de La Cerda y Bayona, J. Nobiliario y Armería General de Navarra. Cuaderno Primero. Madrid: Imprenta de San Francisco de Sales, 1899. https://www.euskalmemoriadigitala.eus/applet/libros/JPG/022344/022344.pdf

- ^ Fernández, Ernesto García. "Ernesto García F. Viana". GARCÍA FERNÁNDEZ, Ernesto "Cristianos y judíos en los siglos XIV y XV en Viana. Una villa navarra en la frontera con Castilla", en Viana. Una ciudad en el tiempo. Analecta Editorial, Pamplona, 2020., pp. 117-158.

- ^ Macaluse, Daniel. "Heraldica". www.mackompras.com (in Spanish). Retrieved 2025-07-26.

- ^ The House of Medrano. Table of genealogy for the descendants of Joan II of Navarre and Philip III of Évreux. https://ramhg.es/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/garrido_mercedes_nobiliarias_reino_navarra_anexo_cuadro_genealogico.pdf

- ^ Las casas señoriales de Olloqui y Belaz de Medrano, 'EL PALACIO DE BELAZ DE MEDRAN0' Page 38 - 43 https://listarojapatrimonio.org/lista-roja-patrimonio/wp-content/uploads/Las-casas-se%C3%B1oriales-de-Olloqui-y-Belaz-de-Medrano.pdf

- ^ Pineda, Pedro (1740). New dictionary, spanish and english and english and spanish : containing the etimology, the proper and metaphorical signification of words, terms of arts and sciences ... por F. Gyles.

- ^ Mosquera de Barnuevo, Francisco (1612). La Numantina de el licen.do don Francisco Mosquera de Barnueuo natural de la dicha ciudad. Dirigida a la nobilissima ciudad de Soria . National Central Library of Rome. Impresso en Seuilla : Imprenta de Luys Estupiñan.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: publisher location (link) - ^ The Pérez de Araciel de Alfaro By Manuel Luis Ruiz de Bucesta y Álvarez Member and Founding Partner of the ARGH. Vice Director of the Asturian Academy of Heraldry and Genealogy Correspondent of the Belgian-Spanish Academy of History Pages. 50–51 https://dialnet.unirioja.es/descarga/articulo/3991718.pdf

- ^ "Informe del patronato de la capellanía perpetua fundada por Diego López de Medrano en la capilla principal del Monasterio de San Francisco de Logroño, de la que son patrones la casa de Agoncillo". www.europeana.eu (in Danish). Retrieved 2025-07-26.

- ^ "Luisa de Medrano, primera mujer en una cátedra de universidad (1484–1527)". lavozdetomelloso.com (in Spanish). Retrieved 2025-07-29.

- ^ ciudad-real.es. "Torre de Galiana de Ciudad Real". www.ciudad-real.es (in Spanish). Retrieved 2025-07-29.

- ^ Tellez, Diego (2015-01-01). "Tomás y Juan Fernández de Medrano: una saga camerana a fines del s. XVI y comienzos del s. XVII". Berceo.

- ^ Fray Domingo Hernáez de Torres, Primera parte de la Crónica franciscana de la Provincia de Burgos, Madrid, 1772; also cited in Cesáreo Goicoechea, Castillos de La Rioja, Logroño, 1949.

- ^ a b c d e f Revista Hidalguía número 9. Año 1955 (in Spanish). Ediciones Hidalguia.

- ^ Rioja, El Día de la (2024-02-19). "Un convento de armas tomar". Retrieved 2024-04-28.

- ^ "Informe del patronato de la capellanía perpetua fundada por Diego López de Medrano en la capilla principal del Monasterio de San Francisco de Logroño, de la que son patrones la casa de Agoncillo". Retrieved 2025-01-12.

- ^ Coursehero. https://www.coursehero.com/file/228312227/00a03278ec4b4838ac4bcd6170b3aa12docx/

- ^ García Turza, Francisco Javier (2000). "La Rioja entre Navarra y Castilla: del mundo agrario al espacio urbano". La Rioja, Tierra Abierta: 177–196. ISBN 978-84-89740-24-2.

- ^ a b Glera, Enrique Martínez (2022-02-15). "La escultura románica de la Iglesia del Hospital de San Juan de Acre en Navarrete". San Juan de Acre.

- ^ a b María Ramírez de Medrano and the Hospital and Convent of San Juan de Acre https://dialnet.unirioja.es/descarga/articulo/8373680.pdf

- ^ "Bishop Martín Bazán [Catholic-Hierarchy]". www.catholic-hierarchy.org. Retrieved 2025-07-26.

- ^ Museo del Prado. https://www.museodelprado.es/coleccion/obra-de-arte/batalla-de-las-navas-de-tolosa-o-de-alacab-ganada/2055fa82-b86c-47db-8e50-48d8dd465520

- ^ "Calle Medrano, Navas de Tolosa". www.foro-ciudad.com. Retrieved 2025-07-26.

- ^ a b V. El sequito Del Rey Fuerte – Pamplona 1922.

- ^ Revista Hidalguía número 9. Año 1955 (in Spanish). Ediciones Hidalguia.

- ^ a b "History of Baeza". Andalucia.com. 2022-11-10. Retrieved 2025-07-26.

- ^ tfpks (2013-01-24). "July 16 - Catholic Spain's fate in the balance at the battle of Las Navas de Tolosa". Nobility and Analogous Traditional Elites. Retrieved 2025-07-26.

- ^ The battle of Las Navas de Tolosa. https://cryhavocfan.org/eng/resource/claymore/files/cl9/eScCl9-2.pdf

- ^ Chaplow, Chris; Watson, Fiona Flores (2014-06-19). "The Battle of Las Navas de Tolosa". Andalucia.com. Retrieved 2025-07-26.

- ^ a b c d "Battle of Las Navas de Tolosa | Almohad Caliphate, Reconquista, 1212 | Britannica". www.britannica.com. 2025-07-09. Retrieved 2025-07-26.

- ^ a b Las Navas de Tolosa. https://ims.leeds.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/sites/29/2019/02/Las-Navas-de-Tolosa.pdf

- ^ a b c d e "The Battle of Las Navas de Tolosa". www.deremilitari.org. Retrieved 2025-07-26.

- ^ "Battle of Las Navas de Tolosa | EBSCO Research Starters". www.ebsco.com. Retrieved 2025-07-26.

- ^ Argamasilla de La Cerda y Bayona, Joaquín (1899). Nobiliario y Armería General de Navarra. Cuaderno Primero (PDF). Madrid: Imprenta de San Francisco de Sales. Retrieved 21 June 2025.

- ^ a b c Loud, G. A. (2011). "Contemporary Texts Describing the Battle of Las Navas de Tolosa (1212)" (PDF). Institute for Medieval Studies, University of Leeds. Retrieved 21 June 2025.

- ^ Wilkinson, Adam (2021-04-01). "The Navarre Crest - All You Need to Know - History And Design". Authentic Basque Country. Retrieved 2025-07-31.

Loud, G. A. (2011). "Contemporary Texts Describing the Battle of Las Navas de Tolosa (1212)" (PDF). Institute for Medieval Studies, University of Leeds. Retrieved 21 June 2025. Argamasilla de La Cerda y Bayona, Joaquín (1899). Nobiliario y Armería General de Navarra. Cuaderno Primero (PDF). Madrid: Imprenta de San Francisco de Sales. Retrieved 21 June 2025.