Kyiv Pechersk Lavra

| Kyiv Pechersk Lavra | |

|---|---|

Києво-Печерська лавра | |

View of the Kyiv Pechersk Lavra | |

Kyiv Pechersk Lavra | |

| 50°26′3″N 30°33′33″E / 50.43417°N 30.55917°E | |

| Location | Pechersk Raion, Kyiv |

| Country | Ukraine |

| Denomination | Eastern Orthodox |

| Website | Official website |

| History | |

| Dedication | Monastery of the Caves |

| Architecture | |

| Architect(s) | Theodosius of Kyiv, Anthony of Kyiv |

| Style | Ukrainian Baroque |

| Years built | 1051 |

| Administration | |

| Diocese | Disputed |

| Official name | Kyiv-Pechersk Lavra |

| Location | Europe |

| Part of | Kyiv: Saint-Sophia Cathedral and Related Monastic Buildings, Kyiv-Pechersk Lavra |

| Criteria | i, ii, iii, iv |

| Reference | 527 |

| Inscription | 1990 (14th Session) |

| Endangered | 2023 |

| Official name | Ансамбль Києво-Печерської Лаври (Ensemble of Kyiv-Pechersk Lavra) |

| Type | Urban Planning, Architecture |

| Reference no. | 260088 |

The Kyiv Pechersk Lavra[1][2] or Kyievo-Pecherska Lavra (Ukrainian: Києво-Печерська лавра), also known as the Kyiv Monastery of the Caves, is a historic lavra or large monastery of Eastern Christianity that gave its name to the Pecherskyi District where it is located in Kyiv.

Since its foundation as the cave monastery in 1051, the Lavra has been a preeminent center of Eastern Christianity in Eastern Europe.[3]

Etymology and other names

Ukrainian: печера, romanized: pechera means lit. cave, which in turn derived from Proto-Slavic *реktera with the same meaning. Ukrainian: лавра, romanized: lavra is used to describe high-ranking male monasteries for monks of the Eastern Orthodox Church. Therefore, the name of the monastery is also translated as Kyiv Cave Monastery, Kyiv Caves Monastery or the Kyiv Monastery of the Caves (from Ukrainian: на печерах).

History

Foundation and early history

The Primary Chronicle contains contradictory information as to when the monastery was founded: in 1051, or in 1074.[4] Anthony, a Christian monk from Esphigmenon monastery on Mount Athos, originally from Liubech of the Principality of Chernigov, returned to Rus' and settled in Kyiv as a missionary of monastic tradition to Kyivan Rus'. He chose a cave at the Berestov Mount that overlooked the Dnieper River and a community of disciples soon grew. Prince Iziaslav I of Kyiv (1024–1078) ceded the whole mount to the Anthonite monks who founded a monastery built by architects from Constantinople.

In 1096 the monastery was plundered by the Cumans. Later it fell victim to the Mongolian invaders, and in 1416 was burned down by forces of Golden Horde ruler Edigey, being rebuilt only in 1470.[5]

At the Kyiv Pechersk Lavra were buried some high-importance personalities from the period when Kyiv was a part of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania: Prince of Kyiv Vladimir Olgerdovich and his son Aleksandras Olelka, the Lithuanian and Ruthenian Grand Duke Švitrigaila, Feodor Ostrogski, Uliana Olshanska (a second wife of the Lithuanian Grand Duke Vytautas the Great), and the Lithuanian Grand Hetman Konstanty Ostrogski, known for commanding the Grand Ducal Lithuanian Army in the victorious Battle of Orsha (1514) versus the Grand Principality of Moscow Army.[6] Mayors of Kyiv, members of the szlachta and Cossack starshyna, as well as church hierarchs also found their burial place in the monastery.[5]

Baroque era and Russian rule

In the 17th century, under the leadership of archimandrites Eliseus Pletenetsky, Zacharias Kopystensky and Peter Mohyla, the monastery stood at the heart of Ukrainian national identity. Kyiv Caves Patericon, which was created by Lavra's monks and soon became a popular reading around the whole Eastern Europe, contributed to the emergence of the symbolic image of Kyiv as a capital of Eastern Orthodoxy. Lavra's printing house, established by Pletenetskyi in the 1620s, started the process of Kyiv's cultural revival, and the monastery's school, founded by Mohyla, introduced European educational trends of the time, leading to a radical reform of education. During the Baroque era Kyiv Pechersk Lavra flourished as a centre of arts and spirituality, and pilgrimage to Kyiv was seen by some as more preferrable than visiting Jerusalem.[5]

Despite the patronage of powerful figures, including Ivan Mazepa and Raphael Zaborovsky, the Annexation of the Metropolis of Kyiv by the Moscow Patriarchate in 1685 started a process of subjugation of the monastery to Russian imperial authority. In 1722, by the decree of Peter I of Russia, the Metropolis of Kyiv was lowered in status to an archbishopric, which made it equal to other subdivisions of the Russian Synodal Church. In the following years, Russian religious traditions, axiology and language were imposed on the Orthodox Church in Ukraine.[7]

Under Russian rule, Pechersk Lavra became a popular place of mass pilgrimage for both the common folk and figures of authority, including the royal family. During the late 19th century numerous guides for pilgrims visiting the monastery were published in Tsarist Russia, contributing to its inclusion into the empire's symbolic space. Among prominent figures buried in Lavra's walls under the Russian rule are Natalia Dolgorukova, Pyotr Rumyantsev and Pyotr Stolypin.[7][5]

Modern history

During the Ukrainian Revolution of the early 20th century attempts to Ukrainize the Lavra failed due to political instability.[7] On 25 January 1918 Metropolitan Vladimir of Kiev was tortured and murdered in the monastery by Bolshevik troops. Eventually, the monastery was disbanded, and in 1926 a museum was opened on its territory.[5] Under German occupation religion services in the monastery were resumed.[7] On 3 November 1941 the main Dormition Cathedral was blown up by Soviet NKVD; Soviet press would falsely accuse the Germans of committing that act. The demolition of the cathedral's ruins continued into the 1960s. After a long period of reconstruction, on 24 August 2000 the reconstructed Dormition Cathedral was solemnly reopened.[5]

Starting from the end of the Second World War, the monastery resumed its activities as part of the Russian Orthodox Church. Over 100 monks lived on Lavra's premises until its new closure by the authorities in 1961.[8]

In 1988 activities of Kyiv Pechersk Lavra were renewed as part of celebrations dedicated to the 1000th anniversary of the Christianization of Kievan Rus'. During the early 1990s the monastery was headed by metropolitan Filaret of Kyiv, whose residence was located on its premises. However, in 1992 ownership over the Lavra was transferred to the Ukrainian Orthodox Church (Moscow Patriarchate) with the support of Kyiv's political leadership.[7] Under the management of the Moscow Patriarchate Lavra became an epicentre of several scandals conncected with its leadership's love for expensive cars and other attributes of wealth, as well as its monks' connections to Russian FSB, veneration of Tsar Nicholas II and spread of anti-Ukrainian propaganda.[5]

Together with the Saint Sophia Cathedral, the Kyiv Pechersk Lavra has been inscribed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site since 1990.[9][nb 1] The monastery complex is considered a separate national historic-cultural preserve (sanctuary), the national status to which was granted on 13 March 1996.[11] The Lavra is not only located in another part of the city, but is part of a different national sanctuary than Saint Sophia Cathedral. While being a cultural attraction, the monastery is once again active, with over 100 monks in residence. It was named one of the Seven Wonders of Ukraine on 21 August 2007.

Until the end of 2022, jurisdiction over the site had been divided between the state museum, National Kyiv-Pechersk Historic-Cultural Preserve,[12] and the Ukrainian Orthodox Church (Moscow Patriarchate) (UOC-MP) as the site of the chief monastery of that Church and the residence of its leader, Onufrius, Metropolitan of Kyiv and All Ukraine.[13][14] In January 2023, the Ukrainian government terminated the UOC-MP's lease of the Dormition Cathedral and the Refectory Church (also known as the Trapezna Church), returning those properties to direct state control.[15][16] It also announced that the Orthodox Church of Ukraine (OCU) had been granted permission to celebrate a Christmas service in the Dormition Cathedral, on 7 January 2023, Orthodox Christmas by the Old Calendar,[16] a service which was celebrated by Metropolitan Epiphanius at 9am that day.[17]

On 10 March 2023, the National Kyiv-Pechersk Historic-Cultural Preserve announced that the 2013 agreement on the free use of churches by the UOC-MP would be terminated on the grounds that the church had violated their lease by making alterations to the historic site, and other technical infractions.[18][19] The UOC-MP was ordered to leave the territory by 29 March.[19] The UOC-MP answered back that there were no legal grounds for the eviction and called it "a whim of officials from the Ministry of Culture."[19] On 17 March 2023 Dmitry Peskov, the press secretary for Russian President Vladimir Putin, stated that the decision of the Ukrainian authorities not to extend this lease to representatives of the UOC-MP "confirms the correctness" of the (24 February 2022) Russian invasion of Ukraine.[19] The UOC-MP did not fully leave Kyiv Pechersk Lavra following 29 March 2023.[20][21]

On 23 July 2025 a religious service in Ukrainian language, the first of that kind in many years, was performed in the Far Caves of Kyiv Pechersk Lavra by Metropolitan Epiphanius of Kyiv.[7]

-

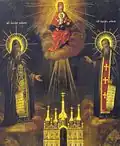

Icon of Saints Anthony and Theodosius, founders of Kyiv Pechersk Lavra

Icon of Saints Anthony and Theodosius, founders of Kyiv Pechersk Lavra -

The Near Caves of the Kyiv Pechersk Lavra. Sketch by the Dutch artist Abraham van Westerveld made in 1651

The Near Caves of the Kyiv Pechersk Lavra. Sketch by the Dutch artist Abraham van Westerveld made in 1651 -

![A lithograph of Pechersk Lavra, Kyiv,[22] National Gallery of Art Library, Washington, D.C.](./_assets_/Perchersk_Lavra%252C_Kyiv_Lithograph.jpg) A lithograph of Pechersk Lavra, Kyiv,[22] National Gallery of Art Library, Washington, D.C.

A lithograph of Pechersk Lavra, Kyiv,[22] National Gallery of Art Library, Washington, D.C. -

Ruins of the Dormition Cathedral in 1958

Ruins of the Dormition Cathedral in 1958 -

A panorama of the monastery, southward view

-

The restored Cathedral of the Dormition, in 2005

The restored Cathedral of the Dormition, in 2005 -

Up-close view of the Great Lavra Belltower with its four tiers in 2005

Up-close view of the Great Lavra Belltower with its four tiers in 2005

Priors

The priors of Kyiv Pechersk Lavra are listed below.

| Years | Names | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Hegumens | ||

| 1051–1062 | Antoniy | Founder of the Pechersk Lavra and pioneer of monasticism in Ukraine[23] |

| 1062–1063 | Varlaam | First hegumen of the monastery, later headed St. Michael's Golden-Domed Monastery[24] |

| 1063–1074 | Theodosius I | Joined the Studite Brethren, initiated the construction of Dormition Cathedral[25] |

| 1074–1077 | Stefan I Bolharyn | One of the first singers in Rus', also served as bishop of Volodymyr, canonized[26] |

| 1077–1088 | Nikon the Great | Before schema known as Hilarion |

| 1088–1103 | John I | In 1096 Cumans led by khan Boniak attacked Kyiv and the Cave Monastery[27] |

| 1108–1112 | Theoktistos | Became a bishop of Chernihiv |

| 1112–1125 | Prokhor | Completion of the Tale of Bygone Years by Nestor the Chronicler[28] |

| 1125–1131 | Timothy / Akindin | |

| 1132–1141 | Pimen the Singer | |

| 1142–1156 | Theodosius II | |

| 1156–1164 | Akindin I | In 1159 the monastery received stauropegic status and since then was known as lavra. |

| Archimandrites | ||

| 1165–1182 | Polycarp I of Pechersk | The first archimandrite; monastery sacked by Andrey Bogolyubsky (1169)[8] |

| 1182–1197 | Basil | |

| 1197-1203 | Theodosius III | Monastery sacked by Rurik Rostislavich (1203)[8] |

| 1203-1232 | Akindin II | Creation of Kyiv Cave Patericon[29] |

| 1232-1238 | Polycarp II | One of the authors of Kyiv Cave Patericon[30] |

| 1238-1249 | Agapit I | Monastery sacked by Batu Khan (1240)[8] |

| 1249-1274 | Serapion | Later moved to Vladimir |

| 1274-1289 | Agapit II | |

| 1289-1292 | Dositheus | |

| 1292-1299 | John II | |

| 1300-? | Azaria | |

| ~1321 | Barsonophius | |

| ~1335 | Maxim | |

| 1370/1377-1395 | David | |

| 1395-1397 | Abrahamius | |

| 1397-1398 | Theodosius IV | |

| 1398-1416 | Nicetas | Monastery sacked by khan Edigey of the Golden Horde |

| 1417-1434 | Ignatius | |

| 1434-1446 | Nicephorus I | |

| 1446-1462 | Nicholas | |

| 1462-1466 | Macarius | |

| 1466-1477 | John III | Monastery rebuilt by Simeon Olelkovich[8] |

| 1477-1482 | Joasaph | Monastery burned down by Tatars[8] |

| 1482-1493 | Theodosius V Woyniłłowicz | |

| 1494-1501/1503 | Philaret | |

| 1501/1503-? | Theodosius VI | |

| ?-? | Sylvester | |

| 1506–1508 | Vassian I Shyshka | |

| 1508-1509 | Jonas I | |

| 1509-1514 | Protasius I | |

| 1514-1524 | Ignatius II | |

| 1524–1525 | Anthony I | |

| 1525-1528 | Ignatius II | |

| 1528–1535 | Anthony I | |

| 1535-1536 | Gennadius | |

| 1536 | Joachim | |

| 1536-1538 | Protasius II | |

| 1539-1540 | Sophronius | |

| 1540 | Joseph I Revut | |

| 1540-1541 | Sophronius | |

| 1541-1546 | Vassian II | |

| 1546-1550 | Joachim II | |

| 1551-1554 | Hilarion I | |

| 1554-1555 | Joseph II | |

| 1556–1572 | Hilarion Pesoczynski | |

| 1572-1574 | Jonas Despotowicz | |

| 1574-1576 | Sylvester of Jerusalem | |

| 1576–1590 | Meletius Chrebtowicz-Bohurynski | Received the title of stauropegion (1586)[8] |

| 1593–1599 | Nycephorus Tur | Start of conflict between Orthodox and Uniate parties after the Union of Brest[8] |

| 1599–1605 | Hipatius Pociej | Member of the Ruthenian Uniate Church |

| 1605–1624 | Yelisei Pletenecki | Established the first printing press in Kyiv (1615)[8] |

| 1624–1627 | Zakhariy Kopystenski | Well-known polemicist and theologian[31] |

| 1627–1646 | Peter Mogila | Opened the monastery school (1631), in 1632 merged into the Kyiv Collegium[8] |

| 1647-1655 | Joseph Tryzna | |

| 1656–1683 | Innocent (Giesel) | Director of the monastery printing house, publisher of Kievan Synopsis (1674)[32] |

| 1684–1690 | Varlaam Yasinski | Subordinated the monastery to the Patriarch of Moscow (1688), while retaining its autonomy[8] |

| 1691–1697 | Meletius Wujachewicz-Wysoczynski | |

| 1697–1708 | Joasaph Krokowski | Theologian and ally of Ivan Mazepa[33] |

| 1709 | Hilarion | |

| 1710–1714 | Athanasius Myslawski | |

| 1715–1729 | Joanicius Seniutovych | A fire in 1718 destroyed the library and archive, as well as most buildings of the monastery[8] |

| 1730–1736 | Roman Kopa | |

| 1737–1740 | Hilarion Nehrebecki | |

| 1740–1748 | Timothy Szczerbacki | Favourite of Elizabeth I of Russia, supporter of Hryhorii Skovoroda[34] |

| 1748–1751 | Joseph Oranski | |

| 1752–1761 | Luka Bilousovych | |

| 1762–1786 | Zosima Valkevych | In 1786 the monastery's property was seized by the Russian government and the tradition of elected leadership was abolished[8] |

| Representatives of Metropolitan bishops of Kyiv | ||

| 1787-1792 | Callist Stefanov | First prior appointed directly by the Metropolitan of Kyiv, who officially attained the title of archimandrite[8] |

| 1792–1795 | Theophilact Slonetsky | |

| 1795-1799 | Hieronym Yanovsky | |

| 1800-1815 | Joel Voskoboinykov | |

| 1815–1826 | Antonius Smyrnytsky | |

| 1826–1834 | Auxentius Halynsky | |

| 1844–1852 | Laurentius Makarov | |

| 1852–1862 | John Petin | |

| 1878–1884 | Hilarion Yushenov | |

| 1884–1892 | Juvenalius Polovtsev | |

| 1893–1896 | Sergius Lanin | |

| 1896-1909 | Antonius Petrushevsky | |

| 1909–1918 | Ambrosius Bulgakov | |

| Priors after the Revolution of 1917 | ||

| 1918-1920 | Antony Khrapovitsky | Opposed autocephaly of the Ukrainian church; removed from his post, later emigrated[35] |

| 1921-1924 | Michael Mytrofanov | Member of Ukrainian Synodal Church; confiscation of many relics by Soviet authorities (1921-22)[8] |

| 1924-1926 | Climent Zheretiyenko | |

| 1925-1929 | Innocent Pustynsky | Member of Ukrainian Synodal Church; closure of the monastery by authorities (1926)[8] |

| 1926–1929 | Hermogen Golubev | |

| Monastery dissolved (1929-1942) | ||

| Representatives of Metropolitan bishops of Kyiv | ||

| 1942-1947 | Valerius Ustymenko | |

| 1947-1953 | Cronides Sakun | |

| 1953-1961 | Nestor Tuhay | |

| Monastery dissolved (1961-1988) | ||

| Representatives of Metropolitan bishops of Kyiv | ||

| 1988-1989 | Jonathan Yeletskikh | |

| 1989-1992 | Eleutherius Dydenko | |

| 1992 | Pitirim Starynsky | Member of Ukrainian Orthodox Church - Moscow Patriarchate (UOC) |

| 1992 | Hyppolit Khilko | Member of UOC |

| 1994-2023 | Paul Lebid | Member of UOC; Dormition Cathdral rebuilt (1998-2000)[8] |

| since 2023 | Abrahamius Lotysh | Member of Orthodox Church of Ukraine |

Buildings and structures

The Kyiv Pechersk Lavra contains numerous architectural monuments, ranging from bell towers to cathedrals to cave systems and to strong stone fortification walls. The main attractions of the Lavra include the Great Lavra Belltower, and the Dormition Cathedral, destroyed in fighting the Germans World War II, and fully reconstructed in the 1990s after the fall of Soviet Union by Ukraine.

Other churches and cathedrals of the Lavra include: the Refectory Church, the Church of All Saints, the Church of the Saviour at Berestove, the Church of the Exaltation of Cross, the Church of the Trinity, the Church of the Nativity of the Virgin, the Church of the Conception of St. Anne, and the Church of the Life-Giving Spring. The Lavra also contains many other constructions, including: the St. Nicholas Monastery, the Kyiv Theological Academy and Seminary, and the Debosquette Wall.

Great Lavra Belltower

The Great Lavra Belltower is one of the most notable features of the Kyiv skyline and among the main attractions of the Lavra. 96.5 meters in height, it was the tallest free-standing belltower at the time of its construction in 1731–1745, and was designed by the architect Johann Gottfried Schädel. It is a Classical style construction and consists of tiers, surmounted by a gilded dome.

Dormition Cathedral

Built in the 11th century, the main church of the monastery was destroyed during the World War II, a couple of months after the Nazi Germany troops occupied the city of Kyiv, during which the Soviet Union conducted the controversial 1941 Khreshchatyk explosions. Withdrawing Soviet troops practiced the tactics of scorched earth and blew up all the Kyiv bridges over Dnieper as well as the main Khreshchatyk street and Kyiv Pechersk Lavra.[36] The destruction of the cathedral followed a pattern of Soviet disregard for cultural heritage, as they previously blew up the ancient St. Michael's Golden-Domed Monastery nearby in the 1930s.[37]

In 1928, the monastery was converted into an anti-religious museum park by the Soviet authorities and after their return no efforts were provided to restore the church. The temple was finally restored in 1995 after Ukraine obtained its independence and the construction was accomplished in two years. The new Dormition Church was consecrated in 2000.[36]

Gate Church of the Trinity

The Gate Church of the Trinity is located atop the Holy Gates, which houses the entrance to the monastery. According to a legend, this church was founded by the Chernihiv Prince Sviatoslav II. It was built atop an ancient stone church which used to stand in its place. After the fire of 1718, the church was rebuilt, its revered facades and interior walls enriched with ornate stucco work made by craftsman V. Stefaovych. In the 18th century, a new gilded pear-shaped dome was built, the facade and exterior walls were decorated with stucco-moulded plant ornaments and a vestibule built of stone attached to the north end. In the early 20th century, the fronts and the walls flanking the entrance were painted by icon painters under the guidance of V. Sonin. The interior of the Gate Trinity Church contains murals by the early 18th century painter Alimpy Galik.

Refectory chambers with Church of the Saints Anthony and Theodosius

The refectory chambers with the Church of the Saints Anthony and Theodosius is the third in a series of temples. The original temple was built in the 12th century and no drawings or visual depictions of it remain. The second temple was built at the time of the Cossack Hetmanate and was disassembled by the Russian authorities in the 19th century. It was replaced with the current temple, often referred to as the Refectory Church of the Kyiv Pechersk Lavra.

The All Saints Church

The All Saints Church, erected in 1696–1698, is a fine specimen of Ukrainian baroque architecture. Characteristic of the church facades are rich architectural embellishments. In 1905, students of the Lavra art school painted the interior walls of the church. The carved wooden iconostasis is multi-tiered and was made for the All Saints church in the early 18th century.

Church of the Saviour at Berestove

The Church of the Saviour at Berestove is located to the North of the Kyiv Pechersk Lavra. It was constructed in the village of Berestove around the start of the 11th century during the reign of Prince Vladimir Monomakh. It later served as the mausoleum of the Monomakh dynasty, also including Yuri Dolgoruki, the founder of Moscow. Despite being outside the Lavra fortifications, the Church of the Saviour at Berestove is part of the Kyiv Pechersk Lavra complex.

Caves

The Kyiv Pechersk Lavra caverns are a system of narrow underground corridors (about 1-1½ metres wide and 2-2½ metres high), along with numerous living quarters and underground chapels. In 1051, the monk Anthony settled in an old cave in a hill near the Kyiv Pechersk Lavra. This cave received additions including corridors and a church, and is now the Far Caves. In 1057, Anthony moved to a cave near the Upper Lavra, now called the Near Caves.

Foreign travellers in the 16th–17th centuries wrote that the catacombs of the Lavra stretched for hundreds of kilometres, reaching as far as Moscow and Novgorod,[38] spreading awareness of the Kyiv Pechersk Lavra.

Library

The notable library of the Lavra was burned during the reign of Peter the Great. On the night of April 21-22, 1718, Orthodox monks — tsarist agents — set fire to the premises of the Lavra, where its library and archive with unique documents and books from the historical past of Ukraine were located.

In 1988, after the restoration of the monastery's activities, library work was resumed. The funds began to be replenished with those publications that the Lavra monks and parishioners managed to save. New books began to be purchased, and some of the books that began to be published by the Lavra printing house restored in 1995 were transferred to the library.

Over 20 years of activity after the revival of the monastery, more than 10 thousand volumes were collected. In 2008, the library was moved to premises that allow the best placement and organization of library funds. Accounting and cataloging of the Lavra library funds were digitized.

Necropolis

There are over a hundred burials in the Lavra. Below are the most notable ones

- Ilya Muromets – in the caves (c. 11th–12th century)

- Nestor the Chronicler – in the Near Caves (c. 1114)

- Saint Kuksha – in the Near Caves (c. 1114)

- Alipy of the Caves – in the Near Caves (c. 1114)

- Agapetus of Pechersk – in the Near Caves (c. 11th century)

- Oleg son of Vladimir II Monomakh – in the Church of the Saviour at Berestove (c. 12th century)

- Eufemia of Kyiv daughter of Vladimir II Monomakh – in the Church of the Saviour at Berestove (1139)

- Yuri Dolgoruki – in the Church of the Saviour at Berestove (1157)

- Vladimir Olgerdovich – Prince of Kyiv, son of the Lithuanian Grand Duke Algirdas[6]

- Aleksandras Olelka – Prince of Kyiv, son of Vladimir Olgerdovich[6][39]

- Skirgaila – regent Grand Duke of Lithuania (1397)

- Feodor Ostrogski[6]

- Uliana Olshanska – a second wife of the Lithuanian Grand Duke Vytautas the Great (1448)[6]

- Švitrigaila – the Lithuanian and Ruthenian Grand Duke (1452)[6]

- Konstanty Ostrogski – near the Cathedral of the Dormition (1530)[6]

- Vasily Kochubey – near the Refectory Church (1708)

- Ivan Iskra – near the Refectory Church (1708)

- Pyotr Stolypin – near the Refectory Church (1911)

- St. Spyridon – in the caves (c. 19th–20th century)

- Pope Clement I – his head in the Far Caves (his remaining relics brought to San Clemente in Rome by Sts. Cyril and Methodius)

During the Soviet era, the bodies of the saints that lay in the caves were left uncovered due to the regime's disregard for religion. However, after the fall of the Soviet Union, the bodies were covered with a cloth and to this day remain in the same state.

-

Imperishable relic of saint Ilya Muromets in Kyiv Pechersk Lavra

Imperishable relic of saint Ilya Muromets in Kyiv Pechersk Lavra -

Monument to Konstanty Ostrogski

Monument to Konstanty Ostrogski

Museum

The Kyiv Pechersk Lavra is one of the largest museums in Kyiv. The exposition is the actual ensemble of the Upper (Near Caves) and Lower (Far Caves) Lavra territories, which house many architectural relics of the past. The collection within the churches and caves includes articles of precious metal, prints, higher clergy portraits and rare church hierarchy photographs.[40] The main exposition contains articles from 16th to early 20th centuries, which include chalices, crucifixes, and textiles from 16th–19th centuries, with needlework and embroidery of Ukrainian masters. The remainder of the collection consists of pieces from the Lavra's Printing House and the Lavra's Icon Painting Workshop.[40]

The museum provides tours of the catacombs, which contain remains of Eastern Orthodox saints or their relics. The Caves are of geological interest because they are excavated into loess ground. They form one of the most extensive occurrences of loess caves in the world.

The Lavra museums include:

- Museum of Historical Treasures of Ukraine

- Book and print history museum

- Museum of Ukrainian Folk Art

- Theater and film arts museum

- State historical library

Images

See also

Notes

- ^ Late 2010 a monitoring mission of UNESCO was visiting the Kyiv Pechersk Lavra to check on situation of the site. At the time the Minister of Culture Mykhailo Kulynyak stated the historic site along with the Saint Sophia Cathedral was not threatened by the "black list" of the organisation.[10] The World Heritage Committee of UNESCO decided in June 2013 that Kyiv Pechersk Lavra, and St. Sofia Cathedral and related monastery buildings would remain on the World Heritage List.[9]

References

- ^ Centre, UNESCO World Heritage. "Kyiv: Saint-Sophia Cathedral and Related Monastic Buildings, Kyiv-Pechersk Lavra". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Retrieved 26 July 2019.

- ^ "Правильное написание столицы Украины на английском языке закреплено в документе ЮНЕСКО - МИД Украины" [The correct spelling of the capital of Ukraine in English is enshrined in a UNESCO document - MFA of Ukraine]. gordonua.com (in Russian). 9 July 2019. Retrieved 26 July 2019.

- ^ Magocsi P.R. A History of Ukraine. University of Toronto Press: Toronto, 1996. p 98.

- ^ Cross & Sherbowitz-Wetzor 1953, p. 7.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Метаморфози Києво-Печерської лаври". Український Тиждень. 5 August 2024. Retrieved 14 August 2025.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Kijevo Pečorų lauros vienuolyno kompleksas". Valstybinė kultūros paveldo komisija (in Lithuanian). Retrieved 25 January 2025.

- ^ a b c d e f "Українська молитва в лаврських печерах". Український Тиждень. 25 July 2025. Retrieved 14 August 2025.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q "Kyivan Cave Monastery". Retrieved 15 August 2025.

- ^ a b Kyiv Pechersk Lavra, St. Sophia Cathedral remain on UNESCO's World Heritage List Archived 24 June 2013 at archive.today, Interfax-Ukraine (20 June 2013)

- ^ ""Софії Київській та Києво-Печерській лаврі "чорний список" ЮНЕСКО не загрожує" – Міністр культури Михайло Кулиняк" ["Sophia of Kyiv and Kyiv-Pechersk Lavra are not threatened by the UNESCO "black list" - Minister of Culture Mykhailo Kulinyak]. Archived from the original on 11 July 2015. Retrieved 23 June 2017.

- ^ "Про надання статусу національного Києво-Печерському держав... - від 13.03.1996 № 181/96" [On granting the status of national Kyiv-Pechersk State... - dated 03.13.1996 No. 181/96]. zakon1.rada.gov.ua. Retrieved 23 June 2017.

- ^ "Сайт Національного Києво-Печерського історико-культурного заповідника" [Site of the National Kyiv-Pechersk Historical and Cultural Reserve]. www.kplavra.kyiv.ua. Retrieved 23 June 2017.

- ^ "General information — Kyiv Holy Dormition Caves Lavra". 14 November 2016. Retrieved 9 December 2019.

- ^ "Head of UOC led solemnities on Synaxis of Near Caves' Venerable Fathers". Kyiv Holy Dormition Caves Lavra. 11 October 2019. Retrieved 12 December 2019.

- ^ "Historical churches of the Kyiv-Pechersk Lavra returned to Ukrainian state from Russia-affiliated church". Euromaidan Press. 5 January 2023.

- ^ a b "Ukraine reclaims Kyiv cathedral amid church dispute". ABC News. 7 January 2023. Retrieved 7 January 2023.

- ^ "Epiphanius for the first time conducts Christmas service in Holy Dormition Cathedral". www.ukrinform.net. 7 January 2023. Retrieved 7 January 2023.

- ^ "Orthodox leader in Kyiv ordered under house arrest by Ukrainian court". PBS NewsHour. 1 April 2023. Retrieved 6 April 2023.

- ^ a b c d "Kremlin says Ukrainian authorities' decision on Ukrainian Orthodox Church of Moscow Patriarchate justifies "special operation"". Ukrainska Pravda. 17 March 2023. Retrieved 17 March 2023.

- ^ "Metropolitan Epiphany urges calm after arrest of abbot". Church Times. 6 April 2023. Retrieved 6 April 2023.

- ^ "Lavra. What's next?". Lb.ua (in Ukrainian). 31 March 2023. Retrieved 31 March 2023.

- ^ Department of Image Collections

- ^ "Saint Anthony of the Caves". 1993. Retrieved 15 August 2025.

- ^ "Varlaam". Retrieved 15 August 2025.

- ^ "Saint Theodosius of the Caves". 1993. Retrieved 15 August 2025.

- ^ "Stefan of Kyiv". 1993. Retrieved 15 August 2025.

- ^ "Boniak". 1984. Retrieved 15 August 2025.

- ^ "Povist' vremennykh lit". 1993. Retrieved 15 August 2025.

- ^ "Kyivan Cave Patericon". Retrieved 15 August 2025.

- ^ "Polikarp, monk". Retrieved 15 August 2025.

- ^ "Kopystensky, Zakhariia". 1989. Retrieved 15 August 2025.

- ^ "Gizel, Innokentii". 1988. Retrieved 15 August 2025.

- ^ "Krokovsky, Yoasaf". 1988. Retrieved 15 August 2025.

- ^ "Shcherbatsky, Tymofii". Retrieved 15 August 2025.

- ^ "Khrapovitsky, Antonii". 1989. Retrieved 15 August 2025.

- ^ a b "1941: уничтожение Успенского собора в Лавре". BBC News Україна (in Russian). 3 November 2016. Retrieved 2 June 2023.

- ^ Гогун, Александр (20 September 2021). "Вандалы-орденоносцы. Как Красная армия взрывала Киев". Радио Свобода (in Russian). Retrieved 2 June 2023.

- ^ Malikenaite, Ruta (2003). Guidebook: Touring Kyiv. Kyiv: Baltia Druk. ISBN 966-96041-3-3.

- ^ Jučas, Mečislovas. "Aleksandras". Visuotinė lietuvių enciklopedija (in Lithuanian). Retrieved 25 January 2025.

- ^ a b Kyiv Sightseeing Guide. Kyiv/Lviv: Centre d'Europe. 2001. ISBN 966-7022-29-3.

Sources

Primary sources

- Cross, Samuel Hazzard; Sherbowitz-Wetzor, Olgerd P. (1953) [1930]. The Russian Primary Chronicle, Laurentian Text. Translated and edited by Samuel Hazzard Cross and Olgerd P. Sherbowitz-Wetzor (PDF). Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Mediaeval Academy of America. p. 325. (The first 50 pages are a scholarly introduction).

- John Herbinius (1675). Religious Kyivan caves or the underground Kyiv (Religiosae Kijovienses Cryptae, Sive Kijovia Subterranea).

Secondary sources

- Kyiv Pechersk Lavra article in Brockhaus and Efron Encyclopedic Dictionary (1907).

- Kyivan Cave Monastery Archived 23 October 2011 at the Wayback Machine in the Encyclopedia of Ukraine Archived 15 August 2009 at the Wayback Machine.

- Schotkina, Kateryna. "Kyiv Pechersk Lavra: Take away and Divide" in Zerkalo Nedeli, 11–17 November 2006.

External links

- Holy Dormition Kyiv-Pechersk Lavra – Official site (in English, Russian, and Ukrainian)

- National Kyiv-Pechersk Historico-Cultural Preserve

- Drawings and Sketches by Students of the Kyiv-Pechersk Lavra Monastery Workshop

- M. Z. Petrenko. Cave labyrinths on the territory of the National Kyiv-Pechersk Historical and Cultural Reserve. Photo essay. Kyiv, Mystetstvo, 1974.

- National Kyiv-Pechersk Historical and Cultural Reserve. A set of postcards. Kyiv, Mystetstvo, 1977.

- Video "Kyiv Pechersk Lavra (4k UltraHD)"

.jpg)

_%D0%9A%D0%B8%D1%97%D0%B2_01.jpg)