Payne–Aldrich Tariff Act

| ||

|---|---|---|

|

27th President of the United States

Presidential campaigns

10th Chief Justice of the United States

Post-presidency

|

||

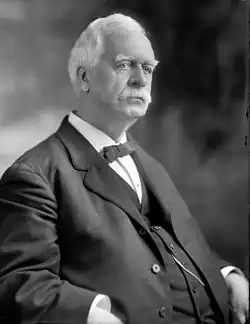

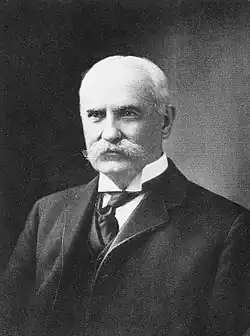

The Payne–Aldrich Tariff Act of 1909 (ch. 6, 36 Stat. 11), sometimes referred to as the Tariff of 1909, is a United States federal law that amended the United States tariff schedules to raise certain tariffs on goods entering the United States.[1][2][3][4] It is named for U.S. representative Sereno E. Payne of New York and U.S. senator Nelson W. Aldrich of Rhode Island.

The Payne–Aldrich tariff began as a measure to enact the "tariff modification" plank of the Republican Party platform, which was generally taken to mean a reduction in most rates and appealed to exporters, particularly Midwestern farmers and agriculture interests. Although the final bill included provisions for a commission to study rates and free trade with the Philippines, the increases in most rates angered progressives, who argued that high protective rates promoted monopoly, and led to a deep split in the Republican Party which culminated in the 1912 presidential primaries.

Background

From the inception of the Republican Party in the 1850s, its candidates and supporters had embraced the American system of political economy and Hamiltonian vision of a protective tariff for the promotion of industrial development. Under this system, high tariff rates were intended to promote higher sales of domestic goods and higher wages for industrial workers; critics argued that the system taxed consumers. In 1896, William McKinley was elected president on a platform proposing tariff increases and his own record as an advocate for protective tariffs. The Dingley Act of 1897 placed average rates on imports at 47% and remained in effect until 1909.

By 1908, however, protective tariffs had begun to fall out of public favor. The growing consolidation and monopolization of heavy industry, including the political power of U.S. Steel and Standard Oil Company, led to public criticism and rejection of the system of high protective tariff rates. In addition to traditional Democratic opposition, progressive insurgents within the Republican Party, primarily from the Midwest, criticized protective tariffs for promoting monopoly.[5]

Legislative provisions

One provision of the Payne Aldrich law provided for the creation of a tariff board to study the problem of tariff modification in full and to collect information on the subject for the use of Congress and the President in future tariff considerations. Another provision allowed for free trade with the Philippines, then under American control. Congress passed the bill officially on April 9, 1909.[6] The bill states it would "take effect the day following its passage."[7] President Taft officially signed the bill at 5:05 pm on August 5, 1909.[8]

The Democrats took control of the House in the 1910 election. President Taft was challenged for reelection in 1912 by former president Theodore Roosevelt for the 1912 Republican nomination. Taft prevailed and Roosevelt and his "progressive" faction formed a new third party. The result was a Democratic landslide making Woodrow Wilson president. The Democrats sharply lowered the tariff in 1913. [9]

Reaction and impact

The Payne Act had the immediate effect of frustrating proponents of reducing tariffs.[10] In particular, the bill greatly angered Progressives, who began to withdraw support from President Taft. Because it increased the duty on print paper used by publishers, the publishing industry viciously criticized the President, further tarnishing his image. Although Taft met and consulted with Congress during its deliberations on the bill, critics charged that he ought to have imposed more of his own recommendations on the bill such as that of a slower schedule. However, unlike his predecessor (Theodore Roosevelt), Taft felt that the president should not dictate lawmaking and should leave Congress free to act as it saw fit.[11] Taft signed the bill with enthusiasm on 5 August 1909, expecting it would stimulate the economy and enhance his political standing. He especially praised the provision empowering the president to raise rates on countries which discriminated against American products, and the provision for free trade with the Philippines.[12]

In an article for the Quarterly Journal of Economics, F. W. Taussig wrote that the congressional debates about the tariffs were "depressing for the economist. There is hardly a gleam of general reasoning of the sort which is applied in our books to questions of international trade... That there should be general acceptance of the protectionist principle, and that the only question in debate should be whether duties were "unreasonably" high, was natural enough. Most people get used to existing conditions, and cannot easily conceive of anything different."[13]

The defection of insurgent Republicans from the Midwest began Taft's slippage of support. It heralded conflicts over conservation, patronage, and progressive legislation. The debate over the tariff thus split the Republican Party into Progressives and Old Guards and led the split party to lose the 1910 congressional election.[14]

Corporate income tax

The bill also enacted a small income tax on the privilege of conducting business as a corporation, which was affirmed in the Supreme Court decision Flint v. Stone Tracy Co. (also known as the Corporation Tax case).[15]

References

- ^ "Vote on Tariff Law Forced in the House" (PDF). The New York Times. April 2, 1910. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-04-09. Retrieved 2008-02-06.

- ^ Willis, H. Parker (1909). "The Tariff of 1909". Journal of Political Economy. 17 (9): 589–619. doi:10.1086/251613. ISSN 0022-3808.

- ^ Willis, H. Parker (1910). "The Tariff of 1909". Journal of Political Economy. 18 (1): 1–33. doi:10.1086/251643. ISSN 0022-3808.

- ^ Willis, H. Parker (1910). "The Tariff of 1909: III". Journal of Political Economy. 18 (3): 173–196. doi:10.1086/251676. ISSN 0022-3808.

- ^ Howard R. Smith, and John Fraser Hart, "The American tariff map." Geographical Review 45.3 (1955): 327–346 online Archived 2020-08-19 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ "Congress passes Payne-Aldrich Act". This Day in History 1909. The History Channel. Archived from the original on 2008-04-11. Retrieved 2008-02-06.

- ^ Sec. 42, 36 Stat. 11 (Pub. Law 61-5). https://govtrackus.s3.amazonaws.com/legislink/pdf/stat/36/STATUTE-36-Pg11b.pdf Archived 2019-10-25 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ 36 Stat. 11 (Pub. Law 61-5). https://govtrackus.s3.amazonaws.com/legislink/pdf/stat/36/STATUTE-36-Pg11b.pdf Archived 2019-10-25 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Claude E. Barfield, "'Our Share of the Booty': The Democratic Party Cannonism, and the Payne–Aldrich Tariff." Journal of American History 57.2 (1970): 308–323 online Archived 2016-12-21 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Paolo E. Coletta, The Presidency of William Howard Taft (1973) pp 45–76.

- ^ Frank W. Taussig, The Tariff History of the United States (8th ed. 1931), pp. 361–408. online

- ^ Stanley D. Solvick, "William Howard Taft and the Payne–Aldrich Tariff." Mississippi Valley Historical Review 50.3 (1963): 424–442 online Archived 2021-03-07 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Taussig, F. W. (1909). "The Tariff Debate of 1909 and the New Tariff Act". The Quarterly Journal of Economics. 24 (1): 1–38. doi:10.2307/1886056. ISSN 0033-5533. JSTOR 1886056.

- ^ Lewis L. Gould, "Western Range Senators and the Payne–Aldrich Tariff." Pacific Northwest Quarterly 64.2 (1973): 49–56 online Archived 2016-12-21 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ John D. Buenker, The Income Tax and the Progressive Era (Routledge, 2018).

Further reading

- Aldrich, Mark. "Tariffs and Trusts, Profiteers and Middlemen: Popular Explanations for the High Cost of Living, 1897–1920." History of Political Economy 45.4 (2013): 693–746.

- Barfield, Claude E. "'Our Share of the Booty': The Democratic Party Cannonism, and the Payne–Aldrich Tariff." Journal of American History (1970) 57#2 pp. 308–323. in JSTOR

- Brawley, Mark R. " 'And we would have the field': US Steel and American trade policy, 1908–1912." Business and Politics 19.3 (2017): 424–453.

- Coletta, Paolo Enrico. The Presidency of William Howard Taft (University Press of Kansas, 1973) pp 61–71.

- Detzer, David W. "Businessmen, Reformers and Tariff Revision: The Payne–Aldrich Tariff of 1909." Historian (1973) 35#2 pp. 196–204.

- Fisk, George. "The Payne–Aldrich Tariff," Political Science Quarterly (1910) 25#1 pp. 35–68; in JSTOR

- Gould, Lewis L. "Western Range Senators and the Payne–Aldrich Tariff." Pacific Northwest Quarterly (1973): 49–56. in JSTOR

- Gould, Lewis L. "New Perspectives on the Republican Party, 1877–1913," American Historical Review (1972) 77#4 pp. 1074–1082 in JSTOR

- Gould, Lewis L. The William Howard Taft Presidency (University Press of Kansas, 2009) 51–64.

- Little, Geoffrey Robert. "" Print paper ought to be as free as the air and water": American Newspapers, Canadian Newsprint, and the Payne-Aldrich Tariff, 1909–1913." American Periodicals: A Journal of History & Criticism 32.1 (2022): 53-69. excerpt

- Mowry, George E. Theodore Roosevelt and the Progressive Movement (1946) pp. 36–65 online.

- Mowry, George E. The Era of Theodore Roosevelt, 1900–1912 (1958) pp. 242–247 read online

- Solvick, Stanley D. "William Howard Taft and the Payne–Aldrich Tariff." Mississippi Valley Historical Review (1963) pp. 424–442 in JSTOR.

- Taussig, Frank W. The Tariff History of the United States (8th ed. 1931), pp. 361–408 online

- Wolman, Paul. Most Favored Nation: The Republican Revisionists and US Tariff Policy, 1897–1912 (U of North Carolina Press, 2000).

.jpg)