Pay toilet

A pay toilet is a public toilet that requires the user to pay. It may be street furniture or be inside a building, e.g. a shopping mall, department store, or railway station. The reason for charging money is usually for the maintenance of the equipment. Paying to use a toilet can be traced back almost 2000 years, to the first century BCE. The charge is often collected by an attendant or by inserting coins into an automatic turnstile; in some freestanding toilets in the street, the fee is inserted into a slot by the door. Mechanical coin operated locks are also used. Some more high tech toilets accept card or contactless payments. Sometimes, a token can be used to enter a pay toilet without paying the charge. Some municipalities offer these tokens to residents with disabilities so these groups aren't discriminated against by the pay toilet. Some establishments such as cafés and restaurants offer tokens to their customers so they can use the toilets for free but other users must pay the relevant charge.

Examples

Europe

In Germany, many lavatories at service stations on the Autobahn have pay toilets with turnstiles, though as in France, customers typically receive a voucher equal to the toilet fee. Elsewhere, while public toilets may not have a set fee, it is customary to provide change to restroom attendants for their services.[1]

In the United Kingdom, pay toilets tend to be common at bus and railway stations, but most public toilets are free to use. Technically, any toilets provided by local government may be subject to a charge by the provider.[2] Pay toilets on the streets may provide men's urinals free of charge to prevent public urination. For example, in London, a few public conveniences are appearing in the form of pop-up toilets. During the daytime, these toilets are hidden beneath the streets, and only appear in the evening.[3] The British English euphemism "to spend a penny" for "to urinate" derives from the use of a pre-decimal penny coin for pay toilet locks.[4]

U.S.

In the United States, pay toilets became much less common from the 1970s, when they came under attack from feminists as well as from the plumbing industry. California legislator March Fong Eu argued that they discriminated against females because men and boys could use urinals for free whereas women and girls always had to pay a dime for a toilet "stall" (i.e. cubicle) in places where payment was mandatory.[5] The American Restroom Association was a proponent of an amendment to the National Model Building Code to allow pay toilets only where there were also free toilets.[6] A campaign by the Committee to End Pay Toilets in America (CEPTIA) resulted in laws prohibiting pay toilets in some cities and states. In 1973, Chicago became the first American city to enact a ban, at a time when, according to The Wall Street Journal, there were at least 50,000 units in America.[7] CEPTIA was successful over the next few years in obtaining bans in New York, New Jersey, Minnesota, California, Florida and Ohio.[8] Lobbying was successful in other states as well, and by the end of the decade, pay toilets were greatly reduced in America. However, they are still in use and produced by the Nik-O-Lok company; many of these laws have since been repealed, such as in Ohio. In 2007, legislators rescinded ORC Ordinance 4101:1-29-02.6.2, the ban on pay facilities, paving the way for operators to charge for public restroom use.[9]

Africa

.jpg)

In Africa, pay toilets are particularly common in informal settlements lacking sewage systems. Of all countries, Ghana has the greatest reliance on public toilets.[10] In Accra, lack of space makes private toilets unrealistic in low-income neighbourhoods.[11] In Kumasi, it has been estimated that 36% of residents use pay toilets, and that "once-daily use of a public toilet by a family of four would cost between US$3.60 and $18 per month depending on the fee charged by the operator of the toilet they use."[12]

History

Some of the earliest documented pay toilets were built around 74 AD in Rome. Emperor Titus Flavius Vespasianus created this method to ease the financial hardships resulting from the many wars that had been fought.[13] The Greco-Roman city of Ephesus was important in ancient times, becoming the trade centre and commercial hub of the ancient world.[14] The Scholastica Baths were built in the 1st century AD, and contained all of the modern amenities for hygiene, including advanced public toilets with marble seats. One had to pay to enter these luxury conveniences, where one could enjoy the use of a pool, use the toilet or socialize.[15]

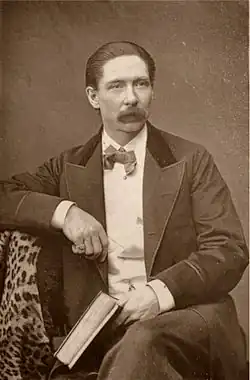

John Nevil Maskelyne, an English stage magician, invented the first modern pay toilet in the late 19th century. His door lock for London toilets required the insertion of a penny coin to operate it, hence the euphemism to "spend a penny".[16]

The first pay toilet in the United States was installed in 1910 in Terre Haute, Indiana.[17]

Criticism

People in developing countries or low incomes, for instance in Accra, may choose to defecate in the open or limit the number of times per day that they use a pay toilet, resulting in undesirable public health consequences.[11]

See also

References

- ^ "The Loneliness of the Klofrau". Der Spiegel. Retrieved 22 December 2014.

- ^ Section 87(3)(c) of the Public Health Act 1936

- ^ "Street Toilets Go Telescopic". BBC News. Retrieved 23 May 2014.

- ^ McAlpine, Fraser. "Fraser's Phrases: 'Spend A Penny'". BBC America. Retrieved 26 January 2021.

- ^ "March Fong Eu". infoplease.com. Retrieved 3 April 2014.

- ^ "Welcome". American Restroom Association (ARA).

- ^ "Clinched fist rising from commodes ends". Missing. Hamilton, Ohio: B–6. August 19, 1976.

- ^ "Clinched fist rising from commodes ends". Journal-News. Hamilton, Ohio. August 19, 1976. p. B–6.

- ^ "Lawriter - OAC - 4101:1-29-02.6.2 Pay facilities. [Rescinded]". codes.ohio.gov. Retrieved 2018-02-12.

- ^ "WHO | Progress on drinking water and sanitation". WHO. Archived from the original on May 14, 2014. Retrieved 2018-08-20.

- ^ a b Peprah, Dorothy; Baker, Kelly K; Moe, Christine; Robb, Katharine; Wellington, Nii; Yakubu, Habib; Null, Clair (2015-10-01). "Public toilets and their customers in low-income Accra, Ghana". Environment and Urbanization. 27 (2): 589–604. Bibcode:2015EnUrb..27..589P. doi:10.1177/0956247815595918. ISSN 0956-2478. S2CID 153987969.

- ^ Greenland, Katie; de-Witt Huberts, Jessica; Wright, Richard; Hawkes, Lisa; Ekor, Cyprian; Biran, Adam (2016-07-08). "A cross-sectional survey to assess household sanitation practices associated with uptake of 'Clean Team' serviced home toilets in Kumasi, Ghana" (PDF). Environment and Urbanization. 28 (2): 583–598. doi:10.1177/0956247816647343. ISSN 0956-2478. S2CID 77012908.

- ^ Langston, A. "The History Behind Pay As You Go Toilets". Retrieved 23 May 2014.

- ^ "Ephesus Ancient City". EPHESUS. Retrieved 21 May 2014.

- ^ "THE PUBLIC TOILETS OF EPHESUS". Retrieved 21 May 2014.

- ^ Lamont, Peter (2004). The Rise of the Indian Rope Trick, (The Biography of a Legend) (1 ed.). Time Warner Books. ISBN 978-0-316-72430-2.

- ^ Gruenstein, Peter (4 Sept 1975) Pay toilet movement attacks capitalism, The Beaver County Times, Retrieved October 19, 2010 (with sarcastic subtitle for 1975, "How about charging air for tires?")