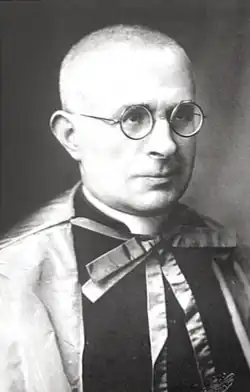

Paul Mulla

Monsignor Paul Mulla | |

|---|---|

| |

| Native name | Ali Mehmet Mulla Zade |

| Church | Catholic Church |

| Archdiocese | Aix-en-Provence |

| Orders | |

| Ordination | 29 June 1911 by Edwin Bonnefoy |

| Personal details | |

| Born | September 6, 1883 |

| Died | March 3, 1959 (aged 75) Rome, Italy |

| Buried | Campo Verano |

| Nationality | Turkish-French |

| Occupation | Islamicist |

| Education | University of Aix-en-Provence |

Paul Ali Mehmet Mulla Zade (6 September 1882 – 3 March 1959), born Ali Mehmet Mulla Zade and commonly known as Paul Mulla, was a Turkish-French Catholic priest, Islamicist, and convert from Islam. He was the godson of Maurice Blondel and served as a professor of Islamic studies in Rome.

Life

Early life

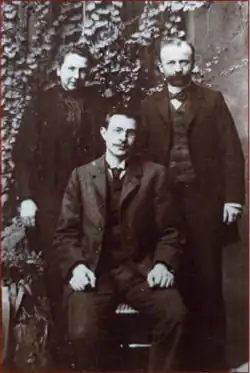

Ali Mehmet Mulla Zade was born in Kandiye on 6 September 1881. He was the eldest son of Pertev Ibrahim Mulla Zade, a doctor and journalist. He was raised bilingual in Turkish and Greek, and became fluent in Arabic, Persian, and French at school. By the year 1895, he had already published Turkish poetry in a journal published in İzmir. In 1895, he was sent to high school in Bouches-du-Rhône. After graduating, he enrolled in the University of Aix-Marseille where he studied under Maurice Blondel.[1]

He was descended of a clerical family from Konya who migrated to Crete after the surrender of the Venetians to the Ottomans in 1669.[2]

Conversion to Christianity

In 1904, Mulla experienced a personal crisis brought on by the death of his twenty-two year old sister Fetine and subsequently failing his doctoral exams in law. During this period, he received the hospitality of his teacher Maurice Blondel, whom he then asked to be his godfather. Blondel accepted without hesitation and Mulla was baptized Paul Marie-Joseph on 25 January 1905 at the chapel of the major seminary of Aix-en-Provence.[3] His godmother, Félicie Boissard, was a labor organizer.[4] During this period of conversion, he was influenced by his study of John Henry Newman, Blaise Pascal, Augustine of Hippo, and Maine de Biran.[5] Mulla's conversion alienated him from his father, who during a visit by Mulla to Crete shortly after his baptism made remarks about killing him.[6]

In a 1945 interview with Eugenio Pellegrino, he recounted his conversion to Christianity. He described a process of having been "shook inside" by an "experience of the natural irreparability of sin and the natural incurability of a sinner." In his conversion from Islam, he experienced a need in order "to recognize the God-man" to "discard the Islamic image of Christ", which he described as having "vaporous features" and an "unreal Passion". This was accompanied by a rejection of a "rationalist prejudice" which "gratuitously rejects, a priori" the possibility of God entering human history.[7] He found belief in the Trinity credible due to a perception of "coherence and unity" among the "divine processions" and described being moved by the Christian belief in divine providence.[8]

In a 1947 autobiographical letter, Mulla describes exploring the various religious and political movements of turn-of-the-century France, including student organizations promoting laicism and anticlericalism, organizations promoting monarchism and integral nationalism, Protestant churches as well as the social Catholicism of Marc Sangnier and Le Sillon. According to Mulla, studying with Maurice Blondel and reading Blondel's dissertation clarified his understanding of modern philosophy. He stated that his decision to convert came after four years of study and personal experience under Blondel's care.[9]

Ordination to the priesthood

After returning to France from Crete, Mulla began seminary studies in Miramas for the Archdiocese of Aix. He was ordained to the priesthood on 29 June 1911 by Edwin Bonnefoy. His first assignment was as a parochial vicar in Fuveau. Mulla remained a Turkish subject at this time, but pursued French citizenship after Ahmet Rıza warned him that people would not understand his way of life and that there would be no place for him in a liberal Turkey. He obtained French citizenship on 3 March 1913, having been at risk of statelessness due to the First Balkan War.[10]

Mulla was then assigned as a parochial vicar at Église Saint-Jean-de-Malte. During the First World War, he was conscripted and served in military hospitals as a nurse in Aix. In 1917, he was promoted to sub-lieutenant and assigned to Beirut where he served as an interpreter for French troops in the Levant. In Beirut, he met Louis Massignon and Eugène Tisserant.[11] During this period, Mulla began to discern his future in the priesthood. Three possibilities set before him were serving Propaganda Fide, further study in Paris, or joining the Jesuits in the Middle East. Due to a papal decree requiring priests in military service to return to their home dioceses, he served as a professor of philosophy at the diocesan college of Aix from 1919 to 1924.[12]

Later life

With the assistance of Maurice Blondel recommending him to Michel d'Herbigny, Mulla was hired in 1924 as a professor at the recently established Pontifical Oriental Institute, where he taught the university's first course in Islamic studies.[13]

From 1924 until his death in 1959, Mulla taught coursework in all areas of Islamic studies.[14] In 1928, Mulla was named a Prelate of Honour of His Holiness by Pope Pius XI[15] and mentioned indirectly in a papal encyclical:[16]

As to the education of the students, besides the dogmatic theology of the dissidents, the explanation of the Oriental Fathers, and of all that appertains to Oriental studies, whether of history, liturgy, archaeology, or other sacred branches of learning, and the languages of various nations, we recall with special gratification how We have been enabled to add to the Byzantine Institutions a chair of Islamic Institutions, a thing hitherto unheard of in Roman centers of learning. By a special favor of Divine Providence, We have been able to place at the head of this Department a man who, born a Turk, and after many years of study, having by God’s help professed the Catholic religion and been ordained to the priesthood, seemed capable of teaching those among his compatriots who were to be destined to the sacred ministry how to present, as well to scholars as to the ignorant, the cause of the One Individual God, and of the Gospel law.

— Pope Pius XI, Rerum Orientalium

In 1927, Mulla began a lifelong correspondence with Jean-Mohammed Abd-el-Jalil, a Moroccan student who was baptized in France and became a Franciscan priest.[17][18] Henri de Lubac described the relationship between Mulla and Abd-el-Jalil as a "quasi-filiation."[19]

He maintained also from 1924 until his death correspondence with Louis Massignon.[20] He was a friend of Giovanni Battista Montini,[21] who participated in a Badaliya prayer group Mulla led in Rome.[22]

Notable students of Mulla included Ignatius Antony II Hayyek, Eugene Bossilkov, Paul II Cheikho, Ignace Abdo Khalifé, Giuseppe Mojoli, Giulio Basetti-Sani, Yves de Montcheuil, and René Voillaume.[23]

Death

Mulla died in Rome on 3 March 1959. He is buried in Campo Verano alongside two Papal Zouaves.[24]

Bibliography

- "Doit-on admettre le vote obligatoire?", Provence Universitaire, April 1902, p. 70.

- "De la logique des institutions. Esquisse d'une histoire naturelle de la loi", Paul Pourcel 1903.

- "Sur la manie dogmatique", Provence Universitaire, July 1913, p. 111-113.

- "La Turquie Nouvelle", Le Petit Éclaireur des Alpes et de Provence, September 1908.

- "Les Jeunes Turcs", L'Éveil démocratique, August 1909.

- "La Question crétoise", Le Petit Éclaireur des Alpes et de Provence, September 1909.

- "Semaines et Semaniers", in Le Faisceau, August 1909.

- "Impressions d'un Jeune Turc à la Semaine Sociale [de Saint-Étienne]", in Le Petit Démocrate, August 1911.

- "La conversion du monde musulman", Toulouse, Editions de l'Apostolat de la Prière, 1923, p. 12.

- "À propos de l'Apologie contre Renan de Nâmiq Kémal", Orientalia Christiana 16 (1929), n. 55, рр. 47-53.

- "Élites des peuples islamisés et des nations européennes modernes", August 1930.

- "Le devoir des nations européennes et de leurs classes élevées envers les peuples de l'Islam", February 1930.

- "Popoli islamici e nazioni europee: La via dell'intervento europeo" in L'Osservatore Romano, 21 February 1931, p. 3.

- "La sagesse coranique d'après un livre récent", in Orientalia Christiana Periodica 2 (1936), pp. 254-260.

- "Perspectives d'après-guerre en pays de mission et conditions d'une évangélisation libre et efficace", in Studia Missionalia 1 (1943) pp. 137-165.

- "Hürriyet", in Le Flambeau, Istanbul, 1949.

References

- ^ Poggi, Vincenzo (2012). "Paul Ali Mehmet Mulla Zade: Islamologo di Tre Papi". Orientalia Christiana Analecta. 292. Rome: Pontificio Istituto Orientale: 17. ISBN 9788872103838.

- ^ Poggi 2012, p. 19.

- ^ Poggi 2012, p. 17-18.

- ^ Launey, Michel. "BOISSARD Félicie". Le Maitron – Dictionnaire bibliographique mouvement social mouvement ouvrier (in French). Retrieved 8 August 2025.

- ^ Poggi 2012, p. 23-25.

- ^ Poggi 2012, p. 32: Lettera di Ali a Félicie Boissard 22.08.1905. Cfr Molette, La verité où je la trouve cit., pp. 23-24. "Papa m'avait dans notre discussion si vive d'il y a dix jours, dit qu'il avait besoin de se retenir pour ne pas m'égorger et je lui avais répondu qu'il était libre de le faire."

- ^ Poggi 2012, p. 93: Da una parte, il cristianesimo mi scuoteva l'interno, svegliando in me il sentimento della serietà drammatica e del valore divino della vita, con la responsabilità infinita, e le sue sanzioni eterne, ravvivando il mio appetito di unità interiore e di coerenza morale, la mia esperienza dell'irreparabilità naturale del peccato, e dell'inguaribilità naturale del peccatore, il mio bisogno di un libera-tore. Dall'altra parte, il cristianesimo mi attirava nelle sue braccia, offrendomi questo salvatore, e mostrandomelo come il Dio incarnato o il Mediatore, come il Verbo di Verità o il Redentore, come il Pane di Vita o il Santificatore. Per riconoscere in Gesù l'Uomo-Dio, dovetti anzitutto disfarmi dell'immagine islamica del Cristo coranico, dalla fisionomia vaporosa, dalla passione non reale; ciò feci, scoprendo nei Vangeli la sua personalità storica. Poi dovetti spogliarmi del pregiudizio razionalista, che gratuitamente rigetta, a priori, l'idea d'una presenza reale dell'Assoluto, e cioè di Dio, che liberamente prende posto nella serie dei fatti contingenti per lievitare la creazione, a modo di fermento, con l'intento di un'elevazione misericordiosa.

- ^ Poggi 2012, p. 94: Nello stesso tempo potei capire la Sapienza increata fattasi uomo rivelarci il segreto delle "processioni divine" in seno all'indivisibile Trinità, e la meraviglia della vocazione dell'uomo a partecipare, mediante l'adozione del Padre, La Redenzione del Figlio, e l'unzione dello Spirito, all'intimità della compagnia di Dio, nella felicità della gloria eterna. Quest'insieme di misteri, impenetrabili nel loro fondo, mi parvero luminosi, sia per la coerenza e l'unità che vi scorgevo tra essi, giacché possono riassumersi tutti nella ripetizione nel tempo d'un mistero d'Amore che riempie l'eternità, sia per le soluzioni che dànno alle grandi domande che la ragione si propone o che i medesimi misteri aiutano quest'ultima a proporsi, fin al punto che credevo poter dire di questi misteri, generalizzando la trase di Pascal a proposito del peccato originale, che l'universo, l'uomo e Dio stesso sono più incomprensibili senza questi, che non siano essi incomprensibili per l'uomo ["De sorte que l'homme est plus inconcevable sans ce mystère que ce mystère n'est inconcevable à l'homme" Pensées II, Ch. XXVI n.111. Soprattutto fui avvinto dalla sublimità del disegno divino sull'umanità, dalla "follia" di quest'iniziativa inaudita della Carità, che colma gli abissi naturali per elevare e soffre il deicidio per salvare la sua creatura: davanti a questa generosità insuperabile di Colui che nihil debuit e tuttavia plus non potuit, io non potevo che rifiutare ogni altro messaggio, all'infuori della Buona Novella, secondo la frase dell'Apostolo: licet angelus de coelo evangelizet vobis praeter id quod accepistis, anathema sit [Gal 1, 8].

- ^ Poggi 2012, p. 101-102.

- ^ Poggi 2012, p. 32.

- ^ Poggi 2012, p. 33-34.

- ^ Poggi 2012, p. 34-37.

- ^ Poggi 2012, pp. 50–51.

- ^ Poggi 2012, p. 52-53.

- ^ Poggi 2012, p. 55.

- ^ Pope Pius XI (8 September 1928). "Rerum Orientalium". Papal Encyclicals. Retrieved 8 August 2025.

- ^ Poggi 2012, p. 15.

- ^ Mulla-Zadé, Paul Mehemet-Ali; Abd-el-Jalil, Jean-Mohammed (2009). Borrmans, Maurice (ed.). Deux frères en conversion du Coran à Jésus: correspondances, 1927-1957. Paris: Les Éditions du Cerf. ISBN 978-2204088121.

- ^ Mulla-Zadé, Paul Mehemet-Ali; Molette, Charles (1988). Mulla: une conscience d'homme dans la lumière de Maurice Blondel. Paris: Téqui. p. 7. ISBN 2852448785.

- ^ Borrmans, Maurice (2012). "Lettres de Mulla-Zadé à Louis Massignon". Orientalia Christiana Analecta. 292. Rome: Pontificio Istituto Orientale: 253-369. ISBN 9788872103838.

- ^ Poggi 2012, p. 83-86.

- ^ Sturnega, Barbara (2011). Padre Giulio Basetti Sani (1912-2001): una vita per il dialogo cristiano-musulmano. Edizioni del Galluzzo per la Fondazione Ezio Franceschini. p. 33. ISBN 9788884503824. Monsignor Mulla, il cui ricordo sempre rimarrà vivo nel cuore di padre Giulio, morì nell'aprile del 1959; a Roma era stato il direttore della Badaliya, il movimento spirituale fondato da Massignon a Damietta nel 1934, animato dalla profonda volontà di formarsi ad uno spirito di comprensione e di amore per il mondo musulmano. Al gruppo romano partecipava in quegli anni anche l'allora mons. Battista Montini, poi eletto a Pontefice con il nome di papa Paolo VI.

- ^ Poggi 2012, p. 73-79.

- ^ Poggi 2012, p. 250.