National Christian Party

National Christian Party Partidul Național Creștin | |

|---|---|

| |

| Leader | Nichifor Crainic Octavian Goga A. C. Cuza |

| Founded | 14 July 1935 |

| Banned | 10 February 1938 |

| Merger of | National Agrarian Party National-Christian Defense League |

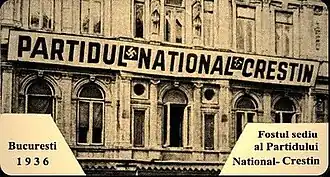

| Headquarters | Bucharest |

| Newspaper | Apărarea Națională (1922-1938) Țara Noastră (1907-1938) Izbânda Național Creștină (1935-1938) |

| Youth wing | National Christian Youth |

| Paramilitary wing | Lancers |

| Ideology | |

| Political position | Far-right |

| Religion | Romanian Orthodoxy |

| Slogan | Hristos, Regele, Națiunea! (Christ, King, Nation!) |

| Election symbol | |

| |

| Party flag | |

| |

| Part of a series on |

| Fascism in Romania |

|---|

|

The National Christian Party (Romanian: Partidul Național Creștin) was a far-right[15], authoritarian, and strongly antisemitic[16] political party in the Kingdom of Romania, active between 1935 and 1938. It was formed by a merger of Octavian Goga's National Agrarian Party (PNA) and A. C. Cuza's National-Christian Defense League (LANC). Among its members was the philosopher Nichifor Crainic, the party's main ideologue. In December 1937, Goga was chosen by King Carol II to form a government that included Cuza; the government lasted only 44 days and was followed by a royal dictatorship under Carol II. The party's members were commonly nicknamed the “Gogo-Cuzists” or simply “Cuzists”, referring to Cuza's wing within the party and the former LANC militants, who were far more notorious than Goga's PNA due to violent street clashes and virulent antisemitic rhetoric throughout the 1920s.

History

Origins

The origins of the National Christian Party trace back to A.C. Cuza's National-Christian Defense League (LANC) and Octavian Goga's National Agrarian Party (PNA), which had barely interacted during their existence before 1935 merger.

The National-Christian Defense League (LANC) as one of the first large-scale fascistic and antisemitic movements in interwar Romania. Founded in 1923 by A.C. Cuza (considered to be the most important ideologue of antisemitism in Romania),[17] at the height of student violence in Romanian universities against Jews and various ethnic minorities, the League quickly gained support throughout the entire region of Moldova. LANC perpetuated and encouraged violent means of propaganda, ranging from street attacks and intimidation of political opponents to direct clashes and provocations against state authorities.[18]

The National Agrarian Party (PNA), however, had a completely different political background and evolution compared to LANC, which was essentially rooted in antisemitism. At its beginnings, the PNA manifested tolerance toward ethnic minorities and actively collaborated with them. Its statute even included provisions regarding the respect for ethnic minorities and their inherent characteristics. Octavian Goga, the founder of the PNA, was considered a friend and protector of the Jewish community in Romania by Leon Press, a Romanian Jewish industrialist and prominent member of the PNA.[19] Beginning in 1933, continuing in 1934 and 1935,[20] Octavian Goga began meeting regularly with Adolf Hitler and later with Benito Mussolini, the National Agrarian Party's ideology gradually started to reflect the influence of German National Socialism and Italian Fascist Corporatism, borrowing various doctrinal elements from both.[21]

The National Christian Party (PNC) inherited a wide range of doctrinal and organizational elements from the National-Christian Cuzist doctrine of the LANC, including blue-shirt uniforms, the Lăncierii paramilitary wing, flags (the Romanian tricolor bearing the swastika),[22] and similar means of action — such as violently repressing the Legionary Movement[23] and carrying out systematic genocides against Jews[24] with its assault battalions.

Preliminaries & founding

By 1935, the political climate in Romania was turbulent, with traditional political parties criticizing King Carol II's royal camarilla, authoritarian tendencies, and lavish lifestyle. Unlike his predecessors, Carol did not rely on political parties and saw himself as above the party leaders. Carol insisted that ministers answer to him rather than to party leaders; he appointed ministers directly and ruled unconstitutionally on several occasions, hence his actions to weaken the parties he did not trust by supporting splinter groups and dissidents, attracting their leading figures to his side, etc.[25] Carol’s camarilla was made up of influential figures in Romanian society, including industrialists Nicolae Malaxa and Max Auschnitt, banker Aristide Blank, economist Mihail Manoilescu, and his mistress Elena Lupescu, whose family controlled a wide network of businesses in Romania.[26]

Parties such as the National Liberal Party-George Brătianu (PNL-B) and the National Peasants' Party (PNȚ), led by Iuliu Maniu, displayed anti-carlist attitudes and, in early 1935, according to a Siguranța report, planned a collective action against Carol's camarilla.[20] King Carol II was aware of the threat the anti-carlist opposition posed to his plans for uncontested authoritarian rule. Carol undertook various actions to weaken the traditional political parties, fostering division within the National Liberal Party by supporting Tătărescu's wing. Carol asked Gheorghe Tătărescu to form a government in 1934, which lasted until 1937. Additionally, he sought to undermine the influence and cohesion of the National Peasants' Party in the Transylvania region by using Ion Mihalache, the PNȚ vice president, against party leader Iuliu Maniu.[27] The PNȚ’s division was accentuated by Vaida-Voevod’s split, who left the party in 1935 to created his own fascist party, the Romanian Front.[28] Vaida-Voevod’s party promoted Numerus Valachicus — a policy that prioritized ethnic Romanians over minorities. The party also organized paramilitary assault battalions, similar to the blue-shirted Lăncieri of the PNC and the green-shirted Iron Guard of the Legionary Movement. This development further splintered Romania’s already fragmented far-right faction, characterized by warlordism, rivalries, and lack of unity in action.

To further weaken the traditional political parties and the strongly anti-carlist Legionary Movement, King Carol II supported the idea of a party that would be loyal to him and to the monarchy. It was a strategic move that helped him push back against the anti-carlists and tighten his authoritarian grip on power, paving the way toward establishing his own royal dictatorship — something he had been striving for ever since his return to the throne in June 1930. Carol wanted to govern, not just reign.[29][30] A.L. Easterman hypothesizes that Carol had placed the PNC in power "to give his people a taste of Fascism", hoping vainly that an ensuing reaction against such policies would sweep away not only the relatively weak National Christians but also the far stronger Legionary Movement.[31]

The National-Christian Defense League was the main rival of the Legionary Movement, with which it frequently clashed, while Goga's National Agrarian Party exhibited a strongly pro-carlist and pro-monarchist stance, which was seen as a safeguard and moderating force against the Cuzist wing within the merged party. The two parties were ideal candidates for a puppet carlist party; as a result, King Carol II, through the Siguranța agent Ion Sân-Giorgiu, monitored both for a period before attempting to bring them closer together for a potential merger. [30] Carol also took into consideration the appeasement of Nazi Germany, which aimed to establish a pro-German regime and actively intervened in the Romanian political scene to support sympathetic or satellite parties — among them the PNC, once it was founded.[32][33]

Nichifor Crainic, a prominent antisemitic ultranationalist ideologue and future vice president of the PNC, was reportedly involved in a secret agreement with Octavian Goga to facilitate a merger with LANC, which was supposedly the reason he left the Legionary Movement to join LANC in February 1935 in the first place. However, German documents indicate that personnel of the Amt Rosenberg also played a role in arranging the merger.[34] For his involvement in the merger, some political scientists consider Crainic a "royal executor," given King Carol II's ambition to create a party that would serve his interests.[35] According to Roland Clark, at one point the National Christian Party had become a tool for Crainic to promote a new political party he intended to found — the Christian Workers' Party.[36]

The merger took place in Iași on July 14, 1935. Delegates of the National Agrarian Party and the National-Christian Defense League from across the country gathered in the presence of the two presidents of the newly founded party — A. C. Cuza as Supreme President and Octavian Goga as Active President — for celebrations and the signing of the constitutive act of the National Christian Party, in the presence of parliamentarians from Iași County.[35]

Activity

The Gogo-Cuzists were the main rivals of the legionaries, and violent disputes between the two parties were particularly intense in the eastern regions of the country. In Bessarabia, for example, the Legionary Movement remained weak, while in Bukovina and parts of Moldova, the strength of the PNC prevented it from securing the entire nationalist-antisemitic electorate. Carol's strategy of weakening both the traditional parties and the Legionary Movement proved effective in this regard.[37] The electoral influence in the eastern regions of Romania was inherited from LANC, which was very active in Moldova, whereas the electoral influence of the PNA was based in Transylvania.

Beginning in February 1935, regional PNC leaders began organizing and establishing local party cells across counties, communes, and villages. Simultaneously, youth organization cells also started to form. In Moldova, where the former LANC had held significant influence, the Cuzist wing of the PNC made use of religious rituals and congresses, with peasants making up the majority of attendees. Such congresses were held in Suceava county, Părhuți commune, where over 3,000 peasants participated. Most notably, a large congress took place in Chișinău, where the number of participants was reportedly as high as 60,000, brought in by train from neighboring counties. In Teleorman County, Lissa commune, after a religious ritual, the local party leader spoke to the peasants about the platform of the PNC, emphasizing the Christian and nationalist aspects of the party. They wanted to show the peasantry that the PNC “takes care of the peasants and helps the poor.” To sensitize the peasants, the local party leaders brought in an old, well-known peasant of the commune (who was also appointed as a cell leader) to speak to those present at the event. With such promises and tactics, the PNC managed to attract a large number of sympathizers by the beginning of August and laid the groundwork for several regional PNC cells across the country.[38]

In February 1935, lawyer and politician Istrate Micescu, a former PNL deputy, briefly collaborated with the Legionary Movement. He founded the Association of Romanian Christian Lawyers, adopting fascist-style rituals and advocating the exclusion of Jewish lawyers from the Ilfov Bar through a Numerus clausus policy. Supported by Legionary lawyers of the Ilfov Bar, he managed to overthrow the bar’s council through a censure motion and intimidation. The alliance with the Legionary Movement proved temporary, as Micescu essentially used its members for political pressure against his opponents. Once president of the Ilfov Bar, he turned against the legionaries, and the rivalry continued throughout the rest of the 1930s. Micescu joined the PNC in 1936 and quickly became a leading figure within the party. He was later appointed Minister of Foreign Affairs in the Goga-Cuza cabinet.[39]

In April 1937, Octavian Goga attempted once again to form a Cuza-Goga-Vaida coalition and to repair relations with C.Z. Codreanu's Legionary Movement — although the appeasement of the Legionary Movement proved to be in vain. In February 1937, when two Cuzists approached Codreanu with the suggestion of forming a united "nationalist front," Codreanu reportedly responded: "Comrades, beware of dogs, whores, and Cuzists."[40] Prior to that, during 1935 and 1936, Goga had pursued similar efforts, either through coalition talks with Vaida-Voevod or by seeking the merger of the Romanian Front into the PNC. Vaida-Voevod was interested in a merger but hesitated, as he feared he would play a minor role in the leadership, since a third president role could not be introduced. Goga pursued a coalition or merger because he trusted the Transylvanian nationalists significantly more than the Cuzist wing of the PNC, which was also distrusted and opposed by Goga’s old followers from the now-merged National Agrarian Party, due to A.C. Cuza’s radical antisemitism.[41]

The NSDAP placed its support behind Octavian Goga and A.C. Cuza — who was referred to as the "mentor of European antisemitism" by Julius Streicher and Alfred Rosenberg — and their party, rather than behind C.Z. Codreanu and his legionaries, although the legionaries also received support from the NSDAP and King Carol II himself at certain points.[42] The leading figures of the NSDAP, among them Alfred Rosenberg — who took a particular interest in the issue of Nazi and fascist-oriented parties in Romania — claimed that the issue had to be resolved in Germany's favor: "The issue of the organizations in Romania harms the Reich’s foreign policy, which must absolutely be taken into account in these times."[43] The support of the NSDAP's Amt Rosenberg facilitated the creation of the party and continued to heavily support it in the period that followed.[44]

On November 8, 1936, 100,000 National Christians marched through Bucharest, imitating the Nazi salute and carrying Romanian tricolor flags bearing the swastika. The march was authorized by the Tătărescu government through Octavian Goga, who maintained contacts with high-ranking Nazi officials. Such demonstrations were never permitted for the Legionary Movement.[37]

The National Christian Party actively opposed the Legionary Movement during the 1937 general elections. Although the Legionary Movement formed an electoral pact on 26 November with the National Peasants' Party (PNȚ) and the National Liberal Party-George Brătianu (PNL-B) to minimize violence and coordinate opposition to King Carol II, the PNC remained outside this agreement. Clashes between legionaries and the PNC-affiliated Cuzists continued throughout the campaign. Between 1935 and 1937, PNC's paramilitary wing – Lăncierii – carried out more terrorist actions and pogroms throughout Romania than the Legionary Movement.[45] On 11 December, the PNC, in cooperation with the PNL (Dinu Brătianu), which was in office at the time through Tătrescu's presidency of the Council of Ministers, successfully challenged the legal eligibility of several Legionary candidates who had participated in the Spanish Civil War. The challenge argued that these individuals had forfeited their Romanian citizenship by serving under a foreign flag. As a result, Legionary candidate lists were disqualified in 18 counties.[46]

The 1937 general elections did not produce a clear parliamentary majority. For the first time in the country’s history, the ruling party failed to win the elections. The governing coalition led by Gheorghe Tătărescu secured only 35.92% of the vote. Iuliu Maniu’s National Peasant Party received 20.40%, while Corneliu Zelea Codreanu’s Totul pentru Țară (the political arm of the Legionary Movement) obtained 15.58%. Faced with a weakened National Liberal Party, unwilling to transfer power to either Maniu or Codreanu, King Carol II turned to the fourth-largest party, the National Christian Party, which had received 9.15% of the vote. Goga was invited to form a government. The resulting cabinet included five PNC deputies, three PNȚ members, and two independents — notably Istrate Micescu as Minister of Foreign Affairs and Armand Călinescu, a known opponent of the Legion, as Minister of the Interior.[47] In his journal, King Carol II reflected on the formation of the new cabinet following the 1937 elections. He wrote:

"Normally, based on the electoral results, I should have invited Codreanu. However, no one outside the legionaries would have approved such a move. For me, it was a total and absolute impossibility. Their use of terrorist methods, their violent antisemitism, their overtly radical foreign policy — especially their desire to overturn existing alliances and their unnatural closeness to Germany — as well as their overall extremist and antisocial approach, made this option unacceptable. Thus, the only remaining constitutional solution was to call upon the National Christian Party of Goga and Cuza." [23]

Under the pretext of opposing the Axis and antisemitism, Carol paradoxically appointed to the government individuals who openly admired Hitler’s radical antisemitism — people whose visits to Nazi Germany[48] were well known and were strongly criticized by the National Peasant Party during the election campaign.[23] For the 1937 electoral campaign alone, the NSDAP, through the German Embassy, sent 17,000 kilograms of printed propaganda materials to the German school in Bucharest, along with didactic materials and 40,000,000 Romanian Lei for the Romanian parties it supported, among them the PNC.[49] Ultimately, for Carol, the PNC was merely a transitional pathway to his own royal dictatorship and a tool for destabilizing the political parties.[50][29]

"GOGA, RUMANIAN NAZI CHIEF, RETURNS FROM BERLIN TRIP

BUCHAREST, Aug. 30. (JTA) – Returning from Berlin, Prof. Octavius Goga, notorious Rumanian anti-Semitic leader, today told newspaper men that the task of his Rumanian National Christian Party was to fight bolshevism and Jewry.

Prof. Goga reported he had received the most favorable impression of the Third Reich."[51]

- Jewish Telegraphic Agency, Vol. II. No. 26 from August 31, 1936.

Notable figures of the PNC

Governance

Formation, policies, reception

The appointment of the National Christian Party (PNC) to form the government happened during a period of severe political turbulence in Romania and the growth of territorial revisionism and fascism in Europe. At that time, Romania’s territorial integrity was particularly threatened by Hungary, Bulgaria, and the USSR. With all the difficult situations occurring at the time, it was unlikely that the PNC government could successfully find remedies, and King Carol II was aware of this, as the PNC was merely a puppet for his own ambitions to establish a royal dictatorship. PNC’s failure to properly govern and address the geopolitical hardships would have allowed Carol to discredit the parliamentary regime and abolish it in favor of his own dictatorship.[52]

Formed on 29 December 1937, the Goga-Cuza government was the first pro-Nazi government in Romania and the second antisemitic government in Europe.[53] The composition of the Goga-Cuza government was determined more by King Carol II and Armand Călinescu than by Goga himself. Carol wanted to be directly involved in governmental affairs, and therefore appointed ministers who would answer directly to him or who were members of his camarilla.[54] The Legionary Movement was outraged by the appointment of Istrate Micescu as Minister of Foreign Affairs — a close associate of King Carol II and leading figure of the PNC — who had been staunchly anti-Legionary throughout the 1930s. As such, on the same day the Goga-Cuza government was formed, the Siguranța reported that 50,000 Legionary workers were planning a march on Bucharest, under the pretext of removing the Minister of Foreign Affairs, Istrate Micescu.[55]

The PNC, however, still needed a majority in the parliament. As such, at Goga's request, King Carol II dissolved the parliament elected in 1937 and set the new dates for the parliamentary elections of 1938 (March 2nd for the Chamber of Deputies and March 4th-6th for the Senate) through a decree-law on January 18, 1938.[56] Despite the dissolution of parliament, it was very unlikely that the PNC would obtain a majority in the upcoming 1938 elections, given that it had obtained only 9.15% of the votes in 1937.[57] Fewer than four weeks after the 1937 elections, a new campaign began in late January, proving to be even more intense in terms of violence than the previous one.[56] To ensure the electoral success of the PNC, Goga replaced the traditional party electoral symbols with points (small solid black circles) intended to mislead illiterate and unexperienced voters.[57] The voters, primarily illiterate, were more familiar with the electoral symbols of the parties than with the names of the candidates on the lists, and even less so with their political programs and ideologies.[58] The PNC list appeared first, marked with a single point and placed on the front page of the ballot, whereas the lists of the other parties were placed on different pages and had more points. At the same time, the Minister of Justice was preparing an electoral decree-law that would grant the party receiving the most votes — even without reaching the 40% threshold — an additional 26%.[57]

The Goga-Cuza government began its term by repudiating Romania’s obligations under the 1919 Treaty of Paris, also known as the Minorities Treaty, imposed at the Paris Peace Conference.[59] It quickly moved to implement a series of antisemitic and racist policies. Commissars were appointed to monitor businesses not owned by ethnic Romanians; Jews were stripped of several commercial rights, particularly in the trade of goods placed under state monopoly; the Jewish press and Jewish cultural institutions were banned, and it was decreed that only ethnic Romanians could work as journalists; Jews were expropriated under the pretext of “needs for public utility” and were prohibited from holding positions in public administration.[53][60]

The avalanche of antisemitic legislation culminated on 21 January 1938, when the Goga-Cuza government promulgated a decree aimed at revising the criteria for citizenship, after alleging that previous cabinets had allowed Jews who fled Ukraine during the Great War to obtain it illegally.[61][62] It required all Jews who had received citizenship in 1918-1919 to reapply for it, and set an impossibly high bar for documentary proof of such citizenship, while providing only 20 days in which this could be achieved.[63] It effectively stripped 250,000 Romanian Jews of Romanian citizenship, one third of the Romanian Jewish population.[62][64] Because of its harsh antisemitic policies and violence, the Goga-Cuza government has been referred to as "more Nazi than the Germans".[65]

"For us there is only one final solution of the Jewish problem — the collection of all Jews into a region that is still uninhabited, and the foundation there of a Jewish nation. And the further away the better."[66]

- Octavian Goga in an interview, The Argus, Monday, January 24, 1938.

"The Jewish problem is an old one here, and it is a Rumanian tragedy. Briefly, we have far too many Jews."[67]

- Octavian Goga in an interview, TIME, Monday, January 31, 1938.

Wilhelm Filderman, lawyer and prominent leader of the Romanian-Jewish community, opposed the Goga-Cuza government’s antisemitic laws. Before the Goga-Cuza government was formed, he went to Paris to warn international Jewish groups and Western governments, meeting French ambassador Adrien Thierry (who was discreetly supporting the formation of a government composed of PNL and PNȚ officials, headed by Dinu Brătianu),[68] Foreign Minister Yvon Delbos, and, with an Alliance Israélite Universelle[n 5] delegate, Prime Minister Léon Blum. Thierry reported to King Carol, warning of possible international repercussions, while British ambassador Sir Reginald Hoare raised concerns with Octavian Goga. Furthermore, Hoare labeled the Goga-Cuza government as fascist and questioned King Carol II’s planned visit to London in March 1938.[68]

Pressure from Filderman and Jewish organizations led the League of Nations to create a committee with delegates from Iran, France, and the United Kingdom to study the issue. On 27 January 1938, during a session of the League of Nations, Foreign Minister Istrate Micescu — who had sought to exclude Jews from the legal profession — was pressed to promise a delay to the antisemitic decrees. Major Jewish international organizations such as the World Jewish Congress, Alliance Israélite Universelle and the Anglo-Jewish Association issued petitions to the League of Nations to protest.[61]

Decline & dismissal

Shortly after the formation of the Goga-Cuza government, reactions started ensuing in all fields of the Romanian society, especially in the economic sphere. On December 31, 1937, the exchange rate of the dollar rose from 160 to 400 lei. The stock exchange was closed until January 10, 1938, and Romanian government bonds depreciated, as Western countries had a strong negative reaction. The country was thus plunged into a severe economic crisis and the more chaotic the situation became, the greater the Carol's control grew. King Carol II could present himself as the sole guarantor of peace and order, capable of saving the country from the threatening fascism.[68] Furthermore, in response to the continuous avalanche of harsh antisemitic policies, the Central Council of the Jews of Romania, led by Wilhelm Filderman, launched somewhat of a “general strike” by halting all commercial and trading activities, withdrawing money from banks, selling stocks, etc. This gesture was imitated by other ethnic minorities and some Romanians in support of the Jewish community, effectively leading to a stock market crash and capital flight.[70]

Unlike A.C. Cuza and the Cuzist wing of the PNC, Octavian Goga understood the real reason he had been chosen to form the government — to repress the Legionary Movement. The Cuzist wing, however, continued to violently clash with legionaries in the streets, under a secret agreement with Minister of the Interior Armand Călinescu that allowed the PNC to use its Lăncieri paramilitary wing (at the time led by Gheorghe A. Cuza, A. C. Cuza's son) to specifically target the legionaries rather than the Jewish population.[23] On the other hand, Goga and his sympathizers avoided personally taking action against the legionaries, aware of the risks they would expose themselves to — a strategy that would later prove beneficial.[54]

The non-aggression pact between Corneliu Zelea Codreanu (LAM), Iuliu Maniu (PNȚ), and Gheorghe Brătianu (PNL-B), signed on 26 November during the 1937 general elections, was falling apart by early 1938. Gheorghe Brătianu had withdrawn from the pact, while Codreanu hesitated to maintain the coalition with Maniu and sought to reconcile with Goga, who was ideologically much closer to him. Between early January and February 9, Codreanu gradually distanced himself from Maniu and moved closer to Goga.[55] Goga began to feel helpless, realizing he was a pawn in Carol’s strategy. With his governing partners — the Cuzists and the former centrist group— effectively obstructing him, he saw an alliance with Codreanu as his only way out. On February 9, 1938, Mihai Sturdza, a member of the high aristocracy and Legionary sympathizer, arranged a meeting between Codreanu and Goga to discuss an agreement. Ultimately, they reached a consensus, and Codreanu decided to suspend the electoral campaign of his political wing for the 1938 elections to support the National Christians.[71]

Due to the paralyzed economy, the deterioration of Romania’s relations with its traditional allies — the United Kingdom, which opposed Goga’s orientation toward the Axis, and France, which threatened to withdraw its security guarantees and arms leases[72] — and its inability to suppress the Legionary Movement, especially following the agreement between Goga and Codreanu, the Goga-Cuza government was dismissed by King Carol II after only 44 days in power.[73][74] On February 10, 1938, Goga had an audience with King Carol II, who said to him: "You made a deal with Codreanu? Very bad, dear Goga, very bad. I will form another government." Goga then resigned.[75]

Electoral history

Legislative elections

| Election | Votes | Percentage | Assembly | Senate | Position | Aftermath |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1937 | 281,167 | 9.3% | 39 / 387

|

0 / 113

|

4th | PNC minority government (1937–1938) |

Notes

- ^ Although anti-Masonry was prescribed in the doctrine of the PNC, it was specific to the Cuzist wing, which had been staunchly anti-Masonic since 1923, in LANC. Freemasonry was seen as a factor contributing to the degradation of the wellbeing of the Romanians.[7]

- ^ A.C. Cuza's son, Gheorghe A. Cuza, was himself a Mason and attended Masonic lodges. This caused harsh criticism from the Iron Guard in the press and became an impediment to reconciliation between the Cuza and Codreanu families, who had been in conflict since late 1925.[8][9][10]

- ^ In a speech delivered on December 10, 1931, A.C. Cuza had expressed his position on Adolf Hitler and aryanism: "I no longer hide the fact that all my sympathies lie with Hitler’s movement in Germany, which I believe will succeed and bring about a profound transformation in the relations between nations, and will restore Aryan and Christian culture against the international Jewish domination."[11]

- ^ A.C. Cuza was fond of Adolf Hitler and personally congratulated him in a letter in 1933, after Hitler came to power.[13] Hitler's doctrine also served as a landmark for LANC's own doctrine and later for that of the PNC. A particularly relevant example is the inspiration Gheorghe A. Cuza drew from the Nuremberg racial laws when the PNC was in power in 1938.[14]

- ^ Cuza believed that the Jews, who, according to him, had a parasitic nature, had elaborated a systemic exploitation system for the peoples of the world by establishing local kahals, which themselves were subordinated to a central organization, "The Universal Kahal", which took the form of the Alliance Israélite Universelle.[69]

References

- ^ Mezarescu, Ion (2018). Partidul Național Creștin 1935-1938 [The National Christian Party 1935-1938] (in Romanian). București: Paideia. pp. 118–119. ISBN 978-606-748-256-0.

- ^ Mezarescu, Ion (2018). Partidul Național Creștin 1935-1938 [The National Christian Party 1935-1938] (in Romanian). București: Paideia. pp. 119–121. ISBN 978-606-748-256-0.

- ^ Schmitt, Oliver Jens (2017). Corneliu Zelea Codreanu. Ascensiunea și căderea „Căpitanului“ [Corneliu Zelea Codreanu: The Rise and Fall of the “Captain”] (in Romanian) (2nd ed.). București: Humanitas (published 2022). p. 194. ISBN 978-973-50-7541-5.

- ^ Mezarescu, Ion (2018). Partidul Național Creștin 1935-1938 [The National Christian Party 1935-1938] (in Romanian). București: Paideia. pp. 64–65. ISBN 978-606-748-256-0.

- ^ Schmitt, Oliver Jens (2017). Corneliu Zelea Codreanu. Ascensiunea și căderea „Căpitanului“ [Corneliu Zelea Codreanu: The Rise and Fall of the “Captain”] (in Romanian) (2nd ed.). București: Humanitas (published 2022). p. 68. ISBN 978-973-50-7541-5.

- ^ Clark, Roland (2015). Sfântă tinereţe legionară. Activismul fascist în România interbelică (ediţia a II-a revăzută şi adăugită) [Holy Legionary Youth. Fascist Activism in Interwar Romania] (in Romanian) (2nd, Revised ed.). Iași: POLIROM (published 2024). pp. 208–209. ISBN 978-973-46-9830-1.

- ^ Schmitt, Oliver Jens (2017). Corneliu Zelea Codreanu. Ascensiunea și căderea „Căpitanului“ [Corneliu Zelea Codreanu: The Rise and Fall of the “Captain”] (in Romanian) (2nd ed.). București: Humanitas (published 2022). p. 68. ISBN 978-973-50-7541-5.

- ^ Moța, Ion (1940). Cranii de lemn [Wooden skulls] (in Romanian) (2nd ed.). Bacău: Vicovia (published 2012). pp. 73–86. ISBN 978-973-7888-28-0.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ^ Clark, Roland (2015). Sfântă tinereţe legionară. Activismul fascist în România interbelică (ediţia a II-a revăzută şi adăugită) [Holy Legionary Youth. Fascist Activism in Interwar Romania] (in Romanian) (2nd, Revised ed.). Iași: POLIROM (published 2024). p. 82. ISBN 978-973-46-9830-1.

- ^ Schmitt, Oliver Jens (2017). Corneliu Zelea Codreanu. Ascensiunea și căderea „Căpitanului“ [Corneliu Zelea Codreanu: The Rise and Fall of the “Captain”] (in Romanian) (2nd ed.). București: Humanitas (published 2022). p. 132. ISBN 978-973-50-7541-5.

- ^ Varzariu, S. (1941). "Recenzii" (PDF). Cetatea Moldovei. 2 (8): 244. Archived from the original on 23 July 2025.

- ^ Călăuza Bunilor Români [The Guide for Good Romanians] (in Romanian). Iași: Editura Ligii Apărării Naționale Creștine. 1925. p. 3.

- ^ Schmitt, Oliver Jens (2017). Corneliu Zelea Codreanu. Ascensiunea și căderea „Căpitanului“ [Corneliu Zelea Codreanu: The Rise and Fall of the “Captain”] (in Romanian) (2nd ed.). București: Humanitas (published 2022). p. 144. ISBN 978-973-50-7541-5.

- ^ Radu, Sorin; Schmitt, Oliver Jens (2023). România interbelică. Modernizare politico-instituțională și discrus național [Interwar Romania. Political-Institutional Modernization and National Discourse] (in Romanian). Iași: POLIROM. p. 501. ISBN 978-973-46-9741-0.

- ^ Payne, Stanley G. (1996). A History of Fascism, 1914–1945. University of Wisconsin Press. p. 15.

- ^ Payne, Stanley G. (1995). A History of Fascism, 1914–1945. University of Wisconsin Press. p. 284.

- ^ Schmitt, Oliver Jens (2017). Corneliu Zelea Codreanu. Ascensiunea și căderea „Căpitanului“ [Corneliu Zelea Codreanu: The Rise and Fall of the “Captain”] (in Romanian) (2nd ed.). București: Humanitas (published 2022). p. 445. ISBN 978-973-50-7541-5.

- ^ Clark, Roland (2015). Sfântă tinereţe legionară. Activismul fascist în România interbelică (ediţia a II-a revăzută şi adăugită) [Holy Legionary Youth. Fascist Activism in Interwar Romania] (in Romanian) (2nd, Revised, Expanded ed.). Iași: POLIROM (published 2024). pp. 60–76. ISBN 978-973-46-9830-1.

- ^ Mezarescu, Ion (2018). Partidul Național Creștin 1935-1938 [The National Christian Party 1935-1938] (in Romanian). București: Paideia. p. 62. ISBN 978-606-748-256-0.

- ^ a b Mezarescu, Ion (2018). Partidul Național Creștin 1935-1938 [The National Christian Party 1935-1938] (in Romanian). București: Paideia. p. 70. ISBN 978-606-748-256-0.

- ^ Mezarescu, Ion (2018). Partidul Național Creștin 1935-1938 [The National Christian Party 1935-1938] (in Romanian). București: Paideia. p. 64. ISBN 978-606-748-256-0.

- ^ Mezarescu, Ion (2018). Partidul Național Creștin 1935-1938 [The National Christian Party 1935-1938] (in Romanian). București: Paideia. p. 102. ISBN 978-606-748-256-0.

- ^ a b c d Schmitt, Oliver Jens (2017). Corneliu Zelea Codreanu. Ascensiunea și căderea „Căpitanului“ [Corneliu Zelea Codreanu: The Rise and Fall of the “Captain”] (in Romanian) (2nd ed.). București: Humanitas (published 2022). p. 281. ISBN 978-973-50-7541-5.

- ^ Radu, Sorin; Schmitt, Oliver Jens (2023). România interbelică. Modernizare politico-instituțională și discrus național [Interwar Romania. Political-Institutional Modernization and National Discourse] (in Romanian). Iași: POLIROM. pp. 500–506. ISBN 978-973-46-9741-0.

- ^ Tănase, Stelian; Vijulie, Elena (2017). Dinastia [The Dynasty] (in Romanian). București: RAO. pp. 133–135, 140. ISBN 978-606-8905-15-0.

- ^ Tănase, Stelian; Vijulie, Elena (2017). Dinastia [The Dynasty] (in Romanian). București: RAO. pp. 134–135. ISBN 978-606-8905-15-0.

- ^ Schmitt, Oliver Jens (2017). Corneliu Zelea Codreanu. Ascensiunea și căderea „Căpitanului“ [Corneliu Zelea Codreanu: The Rise and Fall of the “Captain”] (in Romanian) (2nd ed.). București: Humanitas (published 2022). pp. 193–194. ISBN 978-973-50-7541-5.

- ^ Tănase, Stelian; Vijulie, Elena (2017). Dinastia [The Dynasty] (in Romanian). București: RAO. p. 140. ISBN 978-606-8905-15-0.

- ^ a b Tănase, Stelian; Vijulie, Elena (2017). Dinastia [The Dynasty] (in Romanian). București: RAO. p. 152. ISBN 978-606-8905-15-0.

- ^ a b Mezarescu, Ion (2018). Partidul Național Creștin 1935-1938 [The National Christian Party 1935-1938] (in Romanian). București: Paideia. pp. 75, 229. ISBN 978-606-748-256-0.

- ^ Easterman, A. L. (1942). King Carol, Hitler and Lupescu. London: Victor Gollancz LTD. pp. 258–259.

- ^ Schmitt, Oliver Jens (2017). Corneliu Zelea Codreanu. Ascensiunea și căderea „Căpitanului“ [Corneliu Zelea Codreanu: The Rise and Fall of the “Captain”] (in Romanian) (2nd ed.). București: Humanitas (published 2022). pp. 193–195. ISBN 978-973-50-7541-5.

- ^ Mezarescu, Ion (2018). Partidul Național Creștin 1935-1938 [The National Christian Party 1935-1938] (in Romanian). București: Paideia. pp. 73, 75, 113. ISBN 978-606-748-256-0.

- ^ Clark, Roland (2 February 2012). "Nationalism and orthodoxy: Nichifor Crainic and the political culture of the extreme right in 1930s Romania". Nationalities Papers: The Journal of Nationalism and Ethnicity. 40 (1): 107–126 – via Cambridge University Press.

- ^ a b Mezarescu, Ion (2018). Partidul Național Creștin 1935-1938 [The National Christian Party 1935-1938] (in Romanian). București: Paideia. pp. 78–79. ISBN 978-606-748-256-0.

- ^ Clark, Roland (2015). Sfântă tinereţe legionară. Activismul fascist în România interbelică (ediţia a II-a revăzută şi adăugită) [Holy Legionary Youth. Fascist Activism in Interwar Romania] (in Romanian) (2nd, Revised, Expanded ed.). Iași: POLIROM (published 2024). p. 168. ISBN 978-973-46-9830-1.

- ^ a b Schmitt, Oliver Jens (2017). Corneliu Zelea Codreanu. Ascensiunea și căderea „Căpitanului“ [Corneliu Zelea Codreanu: The Rise and Fall of the “Captain”] (in Romanian) (2nd ed.). București: Humanitas (published 2022). p. 195. ISBN 978-973-50-7541-5.

- ^ Mezarescu, Ion (2018). Partidul Național Creștin 1935-1938 [The National Christian Party 1935-1938] (in Romanian). București: Paideia. pp. 142–145, 152. ISBN 978-606-748-256-0.

- ^ Clark, Roland (2015). Sfântă tinereţe legionară. Activismul fascist în România interbelică (ediţia a II-a revăzută şi adăugită) [Holy Legionary Youth. Fascist Activism in Interwar Romania] (in Romanian) (2nd, Revised, Expanded ed.). Iași: POLIROM (published 2024). pp. 124–125. ISBN 978-973-46-9830-1.

- ^ Schmitt, Oliver Jens (2017). Corneliu Zelea Codreanu. Ascensiunea și căderea „Căpitanului“ [Corneliu Zelea Codreanu: The Rise and Fall of the “Captain”] (in Romanian) (2nd ed.). București: Humanitas (published 2022). p. 261. ISBN 978-973-50-7541-5.

- ^ Mezarescu, Ion (2018). Partidul Național Creștin 1935-1938 [The National Christian Party 1935-1938] (in Romanian). București: Paideia. pp. 152–153. ISBN 978-606-748-256-0.

- ^ Schmitt, Oliver Jens (2017). Corneliu Zelea Codreanu. Ascensiunea și căderea „Căpitanului“ [Corneliu Zelea Codreanu: The Rise and Fall of the “Captain”] (in Romanian) (2nd ed.). București: Humanitas (published 2022). pp. 194, 261, 281. ISBN 978-973-50-7541-5.

- ^ Mezarescu, Ion (2018). Partidul Național Creștin 1935-1938 [The National Christian Party 1935-1938] (in Romanian). București: Paideia. pp. 113, 153. ISBN 978-606-748-256-0.

- ^ Schmitt, Oliver Jens (2017). Corneliu Zelea Codreanu. Ascensiunea și căderea „Căpitanului“ [Corneliu Zelea Codreanu: The Rise and Fall of the “Captain”] (in Romanian) (2nd ed.). București: Humanitas (published 2022). pp. 194–195, 197. ISBN 978-973-50-7541-5.

- ^ Ivan T. Berend, University of California Press, 2001, Decades of Crisis: Central and Eastern Europe Before World War II, p. 337

- ^ Clark, Roland (2015). Sfântă tinereţe legionară. Activismul fascist în România interbelică (ediţia a II-a revăzută şi adăugită) [Holy Legionary Youth. Fascist Activism in Interwar Romania] (in Romanian) (2nd, Revised, Expanded ed.). Iași: POLIROM (published 2024). p. 236. ISBN 978-973-46-9830-1.

- ^ Clark, Roland (2015). Sfântă tinereţe legionară. Activismul fascist în România interbelică (ediţia a II-a revăzută şi adăugită) [Holy Legionary Youth. Fascist Activism in Interwar Romania] (in Romanian) (2nd, Revised, Expanded ed.). Iași: POLIROM (published 2024). p. 239. ISBN 978-973-46-9830-1.

- ^ Mezarescu, Ion (2018). Partidul Național Creștin 1935-1938 [The National Christian Party 1935-1938] (in Romanian). București: Paideia. pp. 54, 64, 73. ISBN 978-606-748-256-0.

- ^ Mezarescu, Ion (2018). Partidul Național Creștin 1935-1938 [The National Christian Party 1935-1938] (in Romanian). București: Paideia. p. 113. ISBN 978-606-748-256-0.

- ^ Mezarescu, Ion (2018). Partidul Național Creștin 1935-1938 [The National Christian Party 1935-1938] (in Romanian). București: Paideia. p. 229. ISBN 978-606-748-256-0.

- ^ "Goga, Rumanian Nazi Chief, Returns from Berlin Trip". Jewish Telegraphic Agency. 1936. p. 6. Archived from the original on 7 August 2024. Retrieved 23 July 2025.

- ^ Mezarescu, Ion (2018). Partidul Național Creștin 1935-1938 [The National Christian Party 1935-1938] (in Romanian). București: Paideia. p. 229. ISBN 978-606-748-256-0.

- ^ a b Radu, Sorin; Schmitt, Oliver Jens (2023). România interbelică. Modernizare politico-instituțională și discrus național [Interwar Romania. Political-Institutional Modernization and National Discourse] (in Romanian). Iași: POLIROM. pp. 500–501. ISBN 978-973-46-9741-0.

- ^ a b Mezarescu, Ion (2018). Partidul Național Creștin 1935-1938 [The National Christian Party 1935-1938] (in Romanian). București: Paideia. p. 232. ISBN 978-606-748-256-0.

- ^ a b Schmitt, Oliver Jens (2017). Corneliu Zelea Codreanu. Ascensiunea și căderea „Căpitanului“ [Corneliu Zelea Codreanu: The Rise and Fall of the “Captain”] (in Romanian) (2nd ed.). București: Humanitas (published 2022). p. 283. ISBN 978-973-50-7541-5.

- ^ a b Ilie, Mihaela (2018). "10th/11th of February 1938 in Interwar Romanian Politics: an Almighty King and a Political Class on its Knees". Revista de Științe Politice. Revue des Sciences Politiques (59): 128–138 – via CEEOL.

- ^ a b c Mezarescu, Ion (2018). Partidul Național Creștin 1935-1938 [The National Christian Party 1935-1938] (in Romanian). București: Paideia. pp. 260–261. ISBN 978-606-748-256-0.

- ^ Sorin, Radu (2002). "SEMNELE ELECTORALE ALE PARTIDELOR POLITICE ÎN PERIOADA INTERBELICĂ (1919-1937)". Apulum (39): 573–586 – via CEEOL.

- ^ Quinlan, Paul D. (1977). Clash over Romania: British and American policies toward Romania, 1938-1947. American Romanian Academy of Arts and Sciences. p. 29. ISBN 9780686232636.

- ^ Clark, Roland (2015). Sfântă tinereţe legionară. Activismul fascist în România interbelică (ediţia a II-a revăzută şi adăugită) [Holy Legionary Youth. Fascist Activism in Interwar Romania] (in Romanian) (2nd, Revised, Expanded ed.). Iași: POLIROM (published 2024). p. 238. ISBN 978-973-46-9830-1.

- ^ a b Radu, Sorin; Schmitt, Oliver Jens (2023). România interbelică. Modernizare politico-instituțională și discrus național [Interwar Romania. Political-Institutional Modernization and National Discourse] (in Romanian). Iași: POLIROM. p. 501. ISBN 978-973-46-9741-0.

- ^ a b Ornea, Z. (1995). Anii treizeci. Extrema dreaptă românească [The Romanian Extreme Right: The Nineteen Thirties] (in Romanian) (4th ed.). POLIROM (published 2015). pp. 308–309. ISBN 978-973-23-3121-7.

- ^ Decree-law no. 169/January 22, 1938

- ^ Levin, Itamar (2001). His Majesty's Enemies: Great Britain's War Against Holocaust Victims and Survivors. Translated by Dornberg, Natasha; Yalon-Fortus, Judith (1st ed.). Praeger. p. 46. ISBN 978-0275968168.

- ^ Tessler, Rudolph (1999). Letter to my children : from Romania to America via Auschwitz. Columbia, Mo. : University of Missouri Press. p. 31.

- ^ "Jews spurned in Rumania". The Argus (Melbourne). January 24, 1938. p. 9. Retrieved 17 August 2025.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "RUMANIA: Bloodsucker of the Villages". TIME. January 31, 1938. p. 1. Archived from the original on 18 October 2009.

- ^ a b c Schmitt, Oliver Jens (2017). Corneliu Zelea Codreanu. Ascensiunea și căderea „Căpitanului“ [Corneliu Zelea Codreanu: The Rise and Fall of the “Captain”] (in Romanian) (2nd ed.). București: Humanitas (published 2022). p. 282. ISBN 978-973-50-7541-5.

- ^ Florian, Alexandru (2022). Elita culturală și discursul antisemit interbelic tradu [The Cultural Elite and Antisemitic Rhetoric in Interwar Romania] (in Romanian). Iași: POLIROM. p. 89. ISBN 978-606-94526-9-1.

- ^ Radu, Sorin; Schmitt, Oliver Jens (2023). România interbelică. Modernizare politico-instituțională și discrus național [Interwar Romania. Political-Institutional Modernization and National Discourse] (in Romanian). Iași: POLIROM. p. 502. ISBN 978-973-46-9741-0.

- ^ Schmitt, Oliver Jens (2017). Corneliu Zelea Codreanu. Ascensiunea și căderea „Căpitanului“ [Corneliu Zelea Codreanu: The Rise and Fall of the “Captain”] (in Romanian) (2nd ed.). București: Humanitas (published 2022). pp. 283–285. ISBN 978-973-50-7541-5.

- ^ Schmitt, Oliver Jens (2017). Corneliu Zelea Codreanu. Ascensiunea și căderea „Căpitanului“ [Corneliu Zelea Codreanu: The Rise and Fall of the “Captain”] (in Romanian) (2nd ed.). București: Humanitas (published 2022). p. 282. ISBN 978-973-50-7541-5.

- ^ Clark, Roland (2015). Sfântă tinereţe legionară. Activismul fascist în România interbelică (ediţia a II-a revăzută şi adăugită) [Holy Legionary Youth. Fascist Activism in Interwar Romania] (in Romanian) (2nd, Revised, Expanded ed.). Iași: POLIROM (published 2024). p. 240. ISBN 978-973-46-9830-1.

- ^ Schmitt, Oliver Jens (2017). Corneliu Zelea Codreanu. Ascensiunea și căderea „Căpitanului“ [Corneliu Zelea Codreanu: The Rise and Fall of the “Captain”] (in Romanian) (2nd ed.). București: Humanitas (published 2022). p. 287. ISBN 978-973-50-7541-5.

- ^ Schmitt, Oliver Jens (2017). Corneliu Zelea Codreanu. Ascensiunea și căderea „Căpitanului“ [Corneliu Zelea Codreanu: The Rise and Fall of the “Captain”] (in Romanian) (2nd ed.). București: Humanitas (published 2022). p. 287. ISBN 978-973-50-7541-5.