Os Africanos no Brasil

| |

| Author | Raimundo Nina Rodrigues |

|---|---|

| Language | Portuguese |

| Subject | Antropology |

| Published | 1932 |

| Publication place | Brazil |

Os Africanos no Brasil (in English: The Africans in Brazil) is a book of the Brazilian physician and anthropologist Nina Rodrigues, published posthumously in 1932, but written between 1890 and 1905. The author, a leading figure in racial theories at the time, explains Brazil's underdevelopment as a consequence of the predominance of black labor.[1] This theory, long accepted as truth, served as the basis for the Brazilian government to further encourage the immigration of White Europeans.[2]

The pioneering essays contained within are dedicated to describing and analyzing various elements, including biological, medical, and criminal aspects, but above all, the social and cultural aspects of the populations descended from slaves in Brazil. The book is divided into nine chapters:

1 - African Origins of Black Brazilians

2 - Black Muslims in Brazil

3 - Black Uprisings in Brazil Before the 19th Century - Palmares.

4 - The Last Africans: Black Nations That Fade Away

5 - African Survivals - Languages and Fine Arts among Black Colonists

6 - Totemic Survivals: Popular Festivals and Folklore

7 - Religious Survivals

8 - Social Value of the Black Races and Peoples that Colonized Brazil and Their Descendants

9 - Psychic Survival in Black Criminality in Brazil

Book Contents

One of the book's main lines of investigation is the African presence in Brazil. In the author's words, they are the "last Africans in Brazil," because, despite long representing something close to the majority (according to the statistics he presents, in 1798, black and mixed-race people (slaves) represented 59.96% of the Brazilian population, and in 1818, black people represented 45.46%), Brazil, he believes, was destined for racial mixing and fusion, a fate he seemed to want to avoid with his racist recommendations. According to Netto,[3] the book "Africans in Brazil" constantly attempts to highlight the dangers posed by the direct or indirect influence of black people on our culture; as well as the disbelief in the flourishing of the Brazilian nation founded on miscegenation, suggesting the whitening of the population via European immigration as a factor of national redemption. The fact is that both Nina Rodrigues and the authors he chose, emblematic representatives of the scientific theories of their time, Herbert Spencer (1820-1903); Charles Darwin (1809-1882), for example, completely ignored the oppressive role of the colonization process to which African and Indigenous peoples were subjected, and the determining power of these in the ways of life of the colonized populations and the development of the "colony."[4]

Schwarcz,[5] in his review of Nina Rodrigues' book "The Fetishist Animism of Black Bahians," highlights that, in this book, three themes seem fundamental to him: the distinction between Sudanese Africans and Bantu peoples, religious syncretism, and the observation that Bahian animist beliefs are widespread, reaching even the elite. In the book "The Africans of Brazil," the distinction between the origins, races, and Black peoples who colonized Brazil is emphasized.

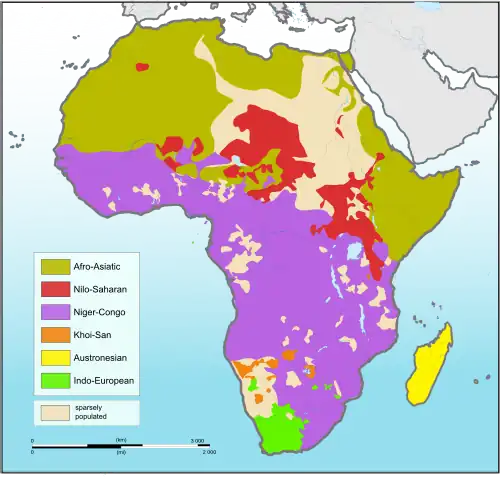

Nina Rodrigues accurately disputes the belief held by "national scientists," according to him, that the Bantu were the Black people who colonized Brazil thanks to the predominance of slave trade from Southern Africa and the islands of the Gulf of Guinea, limiting himself to the following ethnic groups: Congo, Cabinda, Angola (western coast), Macua, and Angicos (eastern coast). He recognizes, however, the numerical supremacy of those who speak the "Tu" or Bantu languages, a position he later revises when attempting to explain, by the same numerical reason, the predominance of the organized ritual form and mythology of the Jeje and Yoruba in religious survivals. According to him, the main, most general, and well-known distinction between groups of Black settlers is: Bantu (Angola, Congo, Mozambique) and Sudanese (Yoruba, Jeje, Fanti). The data and documents collected in his work led him to develop the following framework:

Division of African peoples according to the book

Map of the distribution of the main African language families

1. African Hamites: Fula, Berber, Tuareg

Mixed Hamites: Filani, Black-Fulo

Mixed Hamites and Semites: Eastern Bantu

2. Black Bantu:

a) Western: Kazimba, Schésché, Xexy, Auzaz, Pximba, Tembo, Congo (Martius and Spix), Cameron

b) Eastern: Macua, Anjico (Martius and Spix)

3. Sudanese Blacks:

a) Mande: Mandinga, Malinke, Sosso, Solima

b) Blacks from Senegambia: Wolof, Falupi, Serer, Kruscacheu

c) Blacks from the Gold Coast and Slave Coast: Gas, Tshis, Asantes, Minas and Fantis Jejes or Eués, Nagôs, Beins

d) Central Sudanese: Nupes, Hausas, Adamauas, Bornus, Guruncis, Mossi

4. Black Insulari: Bassós, Bissau, Bijagós

References

- ^ "Brasiliana | Os africanos no Brasil -". www.brasiliana.com.br. Retrieved 2015-11-08.

- ^ "O'DONNEL, Julia e CASTRO, Celso Interpretações do Brasil — "Nina Rodrigues e o "problema" negro", pgs. 25—26. Fundação Getúlio Vargas (2011)" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-05-28. Retrieved 2013-04-23.

- ^ Netto, José A. Os Africanos no Brasil: Raça, Cientificismo e Ficção em Nina Rodrigues. Revista Espaço Acadêmico n44, Jan. 2005 On-line Archived 2011-12-01 at the Wayback Machine Jul. 2011

- ^ CHAVES, Evenice Santos. Nina Rodrigues: sua interpretação do evolucionismo social e da psicologia das massas nos primórdios da psicologia social brasileira. Psicol. estud., Maringá , v. 8, n. 2, p. 29-37, Dec. 2003 . Available from <http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1413-73722003000200004&lng=en&nrm=iso>. access on 25 Aug. 2019. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1413-73722003000200004.

- ^ SCHWARCZ, Lilia Katri Moritz. Rodrigues, Nina. O animismo fetichista dos negros baianos. REVISTA DE ANTROPOLOGIA, SÃO PAULO, USP, 2007, V. 50 Nº 2. Disponível DOCPLAYER Aces. Jun. 2020