Operations Manna and Chowhound

Operation Manna and Operation Chowhound were humanitarian food drops to relieve the Dutch famine of 1944–45 in the German-occupied Netherlands undertaken by Allied bomber crews during the last 10 days of the official war in Europe. Manna (29 April – 7 May 1945), which dropped 7,000 tonnes of food into the still Nazi-occupied western part of the Netherlands, was carried out by British Royal Air Force (RAF) units and squadrons from the Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF), Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF), Royal New Zealand Air Force (RNZAF) and Polish Air Force squadrons in the RAF. Chowhound (1–8 May 1945) dropped 4,000 tonnes and was undertaken by the United States Army Air Forces. In total, over 11,000 tonnes of food were dropped over the 10 days, with the acquiescence of the occupying German forces, to help feed Dutch civilians in danger of starvation.[1] Fighting ended in the Netherlands with the 8 May overall surrender of Nazi Germany, though sporadic fighting continued elsewhere in Europe until remnants of the last of the German army groups had surrendered on 25 May.[2]

After it was realised that Manna and Chowhound would be insufficient, a ground-based relief operation named Operation Faust was launched. On 2 May, 200 Allied trucks began delivering food to the city of Rhenen, behind German lines.

Background

Nazi Germany invaded and occupied the Netherlands in May 1940. The famine began in the occupied Netherlands after the failure of Operation Market Garden (17-25 September 1944), the Allied offensive in southeastern Netherlands aimed at opening up an invasion route into Germany, and the simultaneous strike by Dutch railway workers. After Market Garden, the Germans temporarily prohibited food from being transported from rural eastern Netherlands to the urbanized and heavily populated western Netherlands. The strike by railway workers, which persisted until the end of the war in May 1945, disrupted the transport of food, especially the potato harvest in fall 1944. These two factors plus a diminished level of food reserves held by the Dutch government, the flooding of much agricultural land by the Germans as a defensive measure, a colder than average winter, the forced export of food and workers from the Netherlands to Germany, and Allied bombing contributed to the severity of the famine.[3][4]

Most of the hardships during the famine were suffered in the urban population (about 2.6 million people) in the western Netherlands. Deaths are estimated at about 20,000. At its lowest, the daily ration provided by the Dutch government was two slices of bread and one pint of watery soup per person. The British and American allies were initially reluctant to respond to Dutch requests to send food because they feared the food would fall into German hands. Sweden, Switzerland, neutral countries, and the Red Cross (ICRC) sent shiploads of food to the Netherlands from February to April 1945 and it added an additional 200 to 400 calories daily to the diet of the residents in the cities, but that was far from sufficient to relieve the famine. The official ration was supplemented by a black market and "food trekkers" journeying on foot or by bicycle to the countryside to buy or trade for food.[4][5]

In April 1945, with the surrender of Germany on the near horizon, negotiations between the Germans and Dutch officials resulted in an agreement to request air drops of food by the Allied air forces and for food to enter the Netherlands via military trucks. Remaining in German control was the area west of the Grebbe Line where the four largest cities of the Netherlands were: Amsterdam, Rotterdam, The Hague, and Utrecht. The situation in those cities at the end of April was near catastrophic with official rations amounting to only 364 calories daily.[6]

The negotiations also resulted in a local truce between the advancing Allied armies (mostly Canadian) and the Germans. The Allies feared that as a defensive measure the Germans might destroy the dikes holding back the Atlantic Ocean and flood much of the Netherlands.[7] Twenty-six percent of the Netherlands is below sea level.[8]

Negotiations

On 2 April 1945, German Reichskommissar Arthur Seyss-Inquart told Dutch food officials that he was willing to negotiate a truce in western Netherlands to permit entry of food into German-occupied Netherlands. On 12 April, Seyss-Inquart agreed with the Dutch that if Allied forces halted at the Grebbe Line and ceased military operations in the Netherlands, he would support an Allied effort to send food aid to the Netherlands territory still occupied by the Germans. Dutch Prime Minister in exile Pieter Sjoerds Gerbrandy briefed British Prime Minister Winston Churchill and Prince Bernhard briefed Allied Supreme Commander Dwight Eisenhower on the opportunity to need to aid the starving urban Dutch population. On 23 April, Eisenhower was authrorized to begin planning a relief operation. Eisenhower had already tasked Air Commodore Andrew Geddes with planning.[9]

On 26 April Seyss-Inquart agreed with Dutch authorities to permit air drops of food. On 27 Seyss-Inquart met with British military authorities and on 30 April with Eisenhower's deputy Bedell Smith. The discussions led to an agreement that Allied planes would be permitted to fly in designated corridors without being fired upon by the Germans and that food could be dropped in 10 designated drop zones without interference from the Germans.[10]

Planning

Tasked with planning, British officer Andrew Geddes decided first that air dropping food would be the best method of delivering food. Not enough parachutes were available to drop food by parachute and airplanes couldn't land safely in the Netherlands because the Allies had bombed all the airstrips. They also worried that the planes and crewmen might be taken captive by the Germans if they landed. Geddes experimented with trial drops of sand bags and found that the bags burst hitting the ground when dropped from an altitude of 500 ft (150 m), but that drops at slow speed from 400 ft (120 m) were successful. The low altitude of the drops dictated daytime operations only.[11]

Coordination with the occupying Germans was necessary to designate flight corridors and drop zones to preclude the Germans firing on the aircraft bearing food. The Germans feared that the Allies might use the aid drops as a cover for a military attack. On 26 April Geddes and British general Freddie de Guingand met with German officers in Achterveld, a village in the Canadian-conquered part of the Netherlands. The officers agreed on air corridors, drop zones, and other details, although the German officers did not have the authority to approve the operation. That decision was pushed up to Seyss-Inquart.[12]

Operation Manna

Operation Manna was the British operation, named after the miraculous food described in the Bible. On April 29, despite the fact the fact that the Germans had not yet formally agreed to a ceasefire (Seyss-Inquart would do so the next day), Geddes undertook a test flight to see if the Germans would adhere to the tentative agreement not to shoot at Allied aircraft bearing food. On that morning, two RAF Avro Lancasters carrying food instead of bombs flew to the Netherlands, dropped the food at a racetrack near The Hague, and returned safely to Britain after an operation that lasted only a little more than two hours. With that success, the BBC announced that hundreds of British military aircraft would drop food at six designated drop zones that afternoon. Two-hundred and forty Lancasters dropped 526 tons of food that day. The Lancasters flew at low elevations with German guns pointed at them. The Germans had laid out bed-sheets to identify drop zones. German intelligence personnel stood by to check the food bags as the landed to ensure that no weapons were dropped. Tens of thousands of Dutch citizens descended upon the drop zones. Despite the risk of chaos as hungry people rushed to the drop zones, the reception of the food drops was well organized. Geddes had called on Prince Bernhard, commander of the Dutch army, to organize Dutch reception and distribution committees.[13]

John Funnell, a navigator on the operation, says the first items dropped were tinned food, dried food and chocolate.

At the briefing we were told that a truce had not been negotiated but a broadcast had been made to the Germans telling of our mission, and giving details of our route, height, speed, and destination with a request that we should not be harmed. As we arrived people had gathered already and were waving flags, making signs, etc., doing whatever they could. It was a marvellous sight. The idea was we would cross the Dutch border at 1,000 feet, and then drop down to 500 feet at 90 knots which was just above stalling speed...There was no truce at that point, and as we crossed the coast, we could see the anti-aircraft guns following us about. We were then meant to rise up to 1,000 feet, but because of the anti-aircraft guns we went down to rooftop level. By the time they sighted on us, we were out of sight. A lot of people were surprised we went without armaments...[14]

From April 29 and continuing until May 8, Operation Manna consisted of 3,301 sorties and the dropping of 7,142 tons of food to six locations. The operation was carried out by British, Australian, Canadian, New Zealand, and Polish war planes and crew--plus one Dutchman who piloted a Lancaster. The drop zones were: Katwijk (Valkenburg airfield), The Hague (Duindigt horse race course and Ypenburg airfield), Rotterdam (Waalhaven airfield and Kralingse Plas) and Gouda.The initial drops included military combat rations, but contents became single-item boxes and sacks of flour, tinned meat, sugar, coffee, peas, chocolate and dried eggs.[15]

Operation Chowhound

On the American side, ten bomb groups of the US Third Air Division flew 2,268 sorties beginning 1 May, delivering a total of 4,000 tons.[16] Four hundred B-17 Flying Fortress bombers of the United States Army Air Forces dropped 800 tons of K-rations during 1 to 3 May on Amsterdam Schiphol Airport.

On 1 May 1945, Valkenburg airfield near Leiden was the drop zone for one of many other food drop sites. Gunner Bernie Behrman of the 390th Bomb Group described how his experience of the flight:

The purpose of the mission was Valkenburg airbase. We had no trouble finding the field. There was no anti-aircraft resistance. As I turned for the drop, I could see German soldiers on watch. We dropped the food. Some packages got stuck on the attachment points, but that was no problem. We closed the bomb doors and returned home with a good feeling. The crew on board was a war crew who had a part in blowing things up. After all those destruction flights, we had a very good feeling about this mission. I think the bombers flying low over the drop zones at 150 to 175 knots must have boosted the morale of the people on the ground.[17]

At least one B-17 crew, that of the Stork Club from the 550th Squadron, received battle recognition despite having no guns for their humanitarian mission, as a result of receiving fire from German flak.[18]

Losses

Three aircraft were lost: two in a collision and one due to engine fire.[19] Bullet holes were discovered in several aircraft upon their return, presumably the result of being fired upon by German soldiers who were unaware of, or violating, the ceasefire.[20]

Myths

Earlier, before the start of the airdrops, there had been a distribution of white "Swedish bread" made from Swedish flour that was shipped in and baked locally. A popular myth holds that this bread was dropped from aircraft, but that is a mix-up between the air operations and another humanitarian assistance whereby flour from Sweden was allowed to enter Dutch harbours by ship. Also, no food was dropped using parachutes during operations Manna and Chowhound, as is often wrongfully claimed.

Recognition

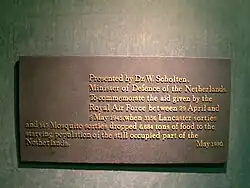

A commemorative plaque to thank the Royal Air Force for their help in mounting Operation Manna was presented in May 1980 by Dr. Willem Scholten, Minister of Defence of the Netherlands and is displayed in the Royal Air Force Museum, Hendon, England. On 28 April 2007, British Air Commodore Andrew Geddes was honoured when a hiking trail in the Rotterdam district of Terbregge, the Air Commodore Geddespath, was named after him. This path goes past the Manna/Chowhound monument in the noise barrier of the northern highway ring road around Rotterdam. The official unveiling of the plaque was performed by Lieutenant-Commander Angus Geddes RN (Geddes's son) from England and Warrant Officer David Chiverton from Australia (Geddes's grandson).

In popular culture

Operation Chowhound was featured in episode 9 of Masters of the Air, a television miniseries for Apple TV+ from Steven Spielberg and Tom Hanks.

References

Notes

- ^ "Arthur Seyss-Inquart". History Learning Site. Archived from the original on 6 January 2014. Retrieved 6 January 2014.

- ^ "Operation Manna-Chowhound: Deliverance from Above". The National WWII Museum. May 6, 2020. Retrieved 19 August 2025.

- ^ de Zwarte, Ingrid (2020). The Hunger Winter. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 43–59. ISBN 9781108836807.

- ^ a b Dankers, Wesley (2023). "Hunger Winter". Traces of War. Translated by Arnold Palthe. Retrieved 1 August 2025.

- ^ de Zwarte 2020, pp. 139–140.

- ^ de Zwarte 2020, p. 104,143-148, 271-272.

- ^ Nufer, Harold F. (1985). "Operation Chowhound: A Precedent for Post-World War II Humanitarian Airlift". Aerospace Historian. 32 (1): 3.

- ^ Schiermeier, Quirin (5 July 2010). "Few fishy facts found in climate report". Nature. 466 (170): 170. doi:10.1038/466170a. PMID 20613812.

- ^ de Zwarte 2020, pp. 143–148.

- ^ de Zwarte 2020, pp. 149–151.

- ^ Dando-Collins, Stephen (2015). Operation Chowhand. New York: Palgrave MacMillan. pp. 98–101. ISBN 9781137279637.

- ^ Dando-Collins 2015, pp. 111–118.

- ^ Dando-Collins 2015, pp. 119–132.

- ^ "Operation Manna--103 Squadron and 576 Squadron--1945". 103 Squadron--RAF. Retrieved 20 August 2025.

- ^ Bambridge, Norman. "Food Drops in Holland in WW2" (PDF). Freeola. Basildon Borough Heritage Society. pp. 4, 7. Retrieved 20 August 2025.

- ^ Manna From Heaven Archived 2008-12-11 at the Wayback Machine – Legion, May 1, 2005, by Ted Barris

- ^ Operation Chowhound: B-17s over Valkenburg, [1], article retrieved 18 April 2025.

- ^ (Tulsa, OK, USA, Tulsa Air and Space Museum and Planetarium docent personal account)

- ^ Vos MacDonald 2002, p. 54.

- ^ Best, Nicholas (2013). Five Days That Shocked the World: Eyewitness Accounts from Europe at the End of World War II. Osprey Publishing. p. 85. ISBN 978-1780960463.

Bibliography

- uncredited. "They Fell Right In The Larder" Aeroplane Monthly, May 1985.

- Hawkins, Ian. B-17s over Berlin: Personal Stories from the 95th Bomb Group (H). Washington, DC: Brassey's, Inc., 1995. ISBN 0-02-881129-1.

- Onderwater, Hans. Operatie "Manna": De Gealieerde Voedseldroppings April/Mei 1945 (in Dutch). Weesp, Netherlands: Romen Luchtvaart, 1985. ISBN 90-228-3776-9.

- Ridder, Willem. Countdown To Freedom. Authorhouse, 2007. ISBN 1-4343-1229-1.

- Vos MacDonald, Joan. Our Mornings May Never Be. General Store Publishing House, 2002. ISBN 1-894263-73-1.

External links

- Lancaster Museum page

- Royal British Legion page

- Operation Manna/Chowhound website

- 8mm movie of Operation Manna in Rotterdam

- Operation Manna at the International Bomber Command Centre Digital Archive.