Octorad

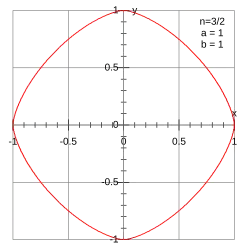

Octorad is the name for a style of stadium architecture in the late 1960s. The term suggests eight radiuses, the design incorporating four arcs of a large circle to comprise most of the structure, and four arcs of a smaller circle to round out the corners. It was a variant on the archetypal multi-purpose stadiums of the time, many of which were either conventionally circular or oval, and were often criticized for poor sight line angles for many spectators at baseball and football games.

The most prominent examples of the octorad style were San Diego Stadium in San Diego, which opened in 1967, and Veterans Stadium in Philadelphia, which opened in 1971. Both stadiums accomplished the goal of providing better sight lines for spectators. However, the architecture of those two stadiums still put a large majority of the fans far away from the action.

Other terms sometimes used for this design were "super circle" and "square circle".

Etymology

The term "octorad" was coined by architect Hugh Stubbins in 1966 while drafting plans for what would become Veterans Stadium. He gave the following explanation for the design upon presenting his stadium proposal to the City of Philadelphia that September:[1]

"It is made with eight points of radii located on two concentric circles so that the arcs of the four long radii locate the points of origin of the four smaller radii on the inner concentric."

Ronald Knabb Jr., who worked alongside Stubbins on the octorad as lead designer, broke down the word's etymology as follows: "'Octo' is Latin for numeral eight. 'Rad' is short for radius. There are eight points of radius on a circle. Connect them with straight lines of chords, and you have the shape of the stadium."[2]

Veterans Stadium

With the new Philadelphia stadium intended to host football for the Eagles and baseball with the Phillies, Stubbins was keen on a design that would maximize seating capacity while providing good viewpoints for spectators. He came up with the octorad, which was described as an "approximate circle" whose shape ensured "no one would get a sore neck from trying to see the game". The additional seats for football would be tarped off for baseball. The shape also would have allowed for easy construction of a roof if desired, and Stubbins expressed hope of installing a dome bigger than the Astrodome's though Veterans Stadium remained open-air.[3] It competed against a traditional rectangular design from George M. Ewing Co. that was criticized by Phillies president R. R. M. Carpenter Jr. for not being baseball-adequate.[4]

The octorad was praised by the Eagles and the city. Eagles owner Jerry Wolman called it "without question the finest we have ever seen", while Philadelphia managing director Fred T. Corletto argued that "because of its unique shape, it will put Philadelphia sports closer to the field of action than in any other multi-purpose stadium in the nation."[1][5] Although construction was delayed due to deadlock over cost, with the octorad exceeding the public funding approved by voters, the city still stressed the desire to use the octorad.[6] Eagles vice president Ed Snider called it a "composite of all problems and compromise"; while the Phillies were initially skeptical, Snider added "both teams loved it" in the end.[4]

Veterans Stadium opened in 1971, standing out from multi-purpose stadiums of the era. Other venues, pejoratively called "cookie cutters", followed circle or oval designs that either only excelled in servicing one sport or was an uncomfortable compromise.[7][8] In contrast, Veterans Stadium was lauded as one of the best for its unique shape and appearance.[9] A Phillies stadium guide after the opening proclaimed it to be "an octorad in architectural sanskrit",[10] while The Sporting News said the venue was "the model stadium if a mathematician became baseball commissioner."[2]

While the octorad technically differed from the cookie-cutter stadiums of the 1960s and 1970s, retrospectives have deemed it ugly and uninspiring. It was equated to a "concrete donut" like the cookie cutters,[11][12] while Baseball Reference felt the building "resembled a concrete ashtray".[13] The News Tribune quipped in 1999 that Veterans Stadium's best characteristic was being the "first, only octorad shaped stadium" before asking, "Does octorad mean bland and ugly?"[14] During the stadium's final year, Jeff Merron of ESPN.com maligned the architecture as unimaginative; he remarked that the final fan to leave should treat it like a bowl of cereal by filling it with Rice Krispies and milk, then watch as the Rice Krispies' "popped" and blew up the building.[15]

Although the octorad sought to be suitable for baseball and football, the design encountered issues that made it difficult to watch from some areas. Veterans Stadium's sight lines were considered "marginally better" for football than baseball, though they were too low for the first rows such that fans had to crane their necks to watch.[16] The Eagles were also concerned the seats were too far away from the playing field for football games. Stubbins commented in 1996 that it was "impossible to put two incompatible sports in the same stadium and have it be perfect for each of them. What I tried to do was make a stadium that would be pretty good for baseball and pretty good for football. And I think that's what it is. But I'm not surprised they're not happy with pretty good."[17]

By the 1990s, both teams were dissatisfied with Veterans Stadium and wished to move to sport-specific venues.[17] The Eagles moved to Lincoln Financial Field in 2003 while the Phillies switched to Citizens Bank Park the following year. Veterans Stadium was imploded in March 2004.[18]

San Diego Stadium

The octorad was also adopted for San Diego Stadium, which opened before Veterans Stadium in 1967 with a horseshoe-based design.[19] Gary Allen, the design director for Frank L. Hope & Associates, felt a superellipse—which utilizes both straight lines and curvature—would be better for a stadium design than a freehand shape. The octorad also resembled the shape of a television, which was growing in mainstream use at the time. John Pastier of the Los Angeles Times wrote the stadium balanced between improved sight lines of contemporary venues with the "spectator intimacy" of baseball parks prior to the Great Depression.[8] It also had a smaller upper deck than Veterans Stadium.[20] The stadium was fully enclosed by 1997, which completed the octorad and preserved its viability well after the design had gone out of style.[21][22]

The stadium's brutalist architecture garnered criticism, contributing to what architect Bob Bangham called a "complete concrete mess".[23][24] Like with Veterans Stadium, San Diego also faced challenges with fan views because of the octorad. Seating was far away from the baseball diamond at Padres games, an experience further exacerbated by the stadium's humid location.[20][22] After its seating capacity expanded for Chargers football following the Padres' departure, the sight lines for many of the low-level seats were so poor that they were closed off. Additional seats along the corners of the playing field were also at a bad angle that required spectators to turn their heads.[20]

San Diego Stadium was torn down in 2021.[25]

Other octorads

In 1972, Abraben, John, Perkins & Will contemplated building an octorad-shaped stadium in Broward County, Florida, which could host the Miami Dolphins.[26] Had it been constructed, the stadium would have hosted 80,000 fans for a variety of other sports including baseball, rodeos, soccer, and midget car racing.[27]

An octorad was also raised as a potential stadium idea when Baltimore pondered building a replacement for Baltimore Memorial Stadium in 1985.[28] Architect Ron Labinski, who was commissioned by the city to lead the design process, described San Diego as his favorite multi-purpose venue.[29] Since he was asked to build an open-air venue that could be used for multiple sports, Labinski noted the octorad was the "best shape for a stadium".[28] Labinski ultimately developed separate buildings for the Orioles (Oriole Park at Camden Yards) and Ravens (M&T Bank Stadium) that catered to their respective sports.[30]

References

- ^ a b "Philadelphia stadium articles". The Philadelphia Inquirer. September 16, 1966. Retrieved August 12, 2025 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b "Veterans Stadium". This Great Game. Retrieved August 13, 2025.

- ^ "Molter Gets Chair in Slayings". The Philadelphia Inquirer. June 19, 1966. Retrieved August 12, 2025 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b Feist, William F.; Keith, C. Allen (November 11, 1966). "New 'Composite' Study of Stadium Design Ordered". The Philadelphia Inquirer. Retrieved August 12, 2025 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Phils, Eagles Like The New Stadium Plans". The Daily Times. AP. September 16, 1966. Retrieved August 12, 2025 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Fidati, Bill (November 15, 1966). "Stadium's Exec Architect Up in Aor Over Latest Idea, Cost". Retrieved August 12, 2025 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Shenk, Larry (November 29, 2023). "A Domed Veterans Stadium?". Major League Baseball. Retrieved August 12, 2025.

- ^ a b Pastier, John (June 11, 1973). "San Diego Leads League in Stadiums". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved August 12, 2025 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Tannenbaum, Michael (March 21, 2019). "Twitter reacts to 15-year anniversary of Veterans Stadium demolition". PhillyVoice. Retrieved August 12, 2025.

- ^ Karmosky, Charles (April 15, 1971). "Stadiums sprout like mushrooms". Daily Press. Retrieved August 12, 2025 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Sullivan, Paul Francis (June 7, 2018). "MLB Should Have Kept Just One Concrete Donut Stadium". Bleacher Report. Retrieved August 12, 2025.

- ^ Jackson, Frank (September 3, 2024). "Square Pegs, Round Holes, and Concrete Doughnuts". Seamheads.com. Retrieved August 12, 2025.

- ^ "Veterans Stadium". Baseball Reference. Retrieved August 13, 2025.

- ^ "Best and worst of baseball's ballparks". The News Tribune. July 11, 1999. Retrieved August 12, 2025 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Merron, Jeff. "It's so hard to say goodbye". ESPN.com. ESPN. Retrieved August 13, 2025.

- ^ "Veterans Stadium". Clem's Baseball Blog. Retrieved August 13, 2025.

- ^ a b Sokolove, Michael (March 10, 1996). "Eagles and Phils draw battle lines in stadium quest". The Philadelphia Inquirer. Retrieved August 13, 2025 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Rowan, Tommy. "Veterans Stadium bit the dust on this week in Philly history". The Philadelphia Inquirer.

- ^ Reichard, Kevin (October 4, 2024). "In memoriam: Oakland Coliseum". Ballpark Digest. Retrieved August 12, 2025.

- ^ a b c "Jack Murphy Stadium". Clem's Baseball Blog. Retrieved August 13, 2025.

- ^ "Bob Murphy's Brother Jack Murphy & the San Diego Stadium Named After Him". centerfield maz. February 3, 2011. Retrieved August 13, 2025.

- ^ a b "San Diego Stadium – until 2020". StadiumDB.com. Retrieved August 13, 2025.

- ^ Smith, Dan. "Diamonds of the West". Eichler Network. Retrieved August 13, 2025.

- ^ Carbone, Nick (May 9, 2012). "Top 10 Worst Stadiums in the U.S. – 4. Qualcomm Stadium, San Diego". Time. Retrieved August 12, 2025.

- ^ "WATCH: Final Piece of San Diego Stadium Torn Down". KNSD. March 22, 2021. Retrieved August 13, 2025.

- ^ Bruce, Celiene (February 9, 1972). "Dream Stadium Has $54 Million Price". Fort Lauderdale News. Retrieved August 12, 2025 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Bruce, Celiene (February 5, 1972). "Broward Site For Major Stadium?". Fort Lauderdale News. Retrieved August 12, 2025 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b Goldstein, Alan (January 16, 1985). "It's 'R.I.P. Memorial Stadium'". The Baltimore Sun. Retrieved August 13, 2025 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Reimer, Susan (January 16, 1985). "Labinski, the architect, is No. 1 in his league". The Baltimore Sun. Retrieved August 13, 2025 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Sandomir, Richard (February 9, 2023). "Ron Labinski, Who Designed a Cozier Future for Stadiums, Dies at 85". The New York Times. Retrieved August 12, 2025.