Nullotitan

| Nullotitan Temporal range: Late Cretaceous,

| |

|---|---|

| |

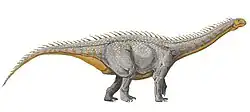

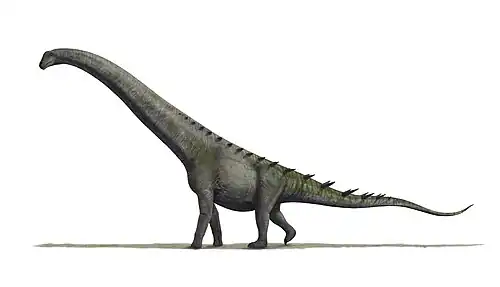

| Skeletal reconstruction of Nullotitan | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Clade: | Saurischia |

| Clade: | †Sauropodomorpha |

| Clade: | †Sauropoda |

| Clade: | †Macronaria |

| Clade: | †Titanosauria |

| Clade: | †Colossosauria |

| Genus: | † Novas et al., 2019 |

| Type species | |

| †Nullotitan glaciaris Novas et al., 2019

| |

Nullotitan (meaning "Nullo's giant", in honor of paleontologist Francisco Nullo) is an extinct genus of lithostrotian titanosaur dinosaurs from the Late Cretaceous Chorrillo Formation of Santa Cruz Province, Argentina. The genus contains a single species, Nullotitan glaciaris. It was a contemporary of the ornithopod Isasicursor, which was described in the same paper.

Discovery and naming

In 1980, geologist Francisco E. Nullo noticed the presence of sauropod bones on a hillside of the Estancia Alta Vista, south of the Centinela River in the Santa Cruz province of Argentina. He reported these finds to paleontologist José Bonaparte, who excavated a large cervical vertebra the following year and reported it as cf. Antarctosaurus. The old site was relocated and new excavations were carried out between 13 and 17 January and 14 to 19 March 2019, and a new site was discovered on the Estancia La Anita. A new fauna came to light in an area of 2,000 square kilometres (770 square miles), including six concentrations of bones that could be assigned to the original find, which was now recognized as a new sauropod species.[1]

In 2019, the type species Nullotitan glaciaris was named and described by Fernando Emilio Novas and colleagues. The genus name, Nullotitan, honors Nullo, linking his name to the Greek "titan", referring to the powerful Titans of Greek mythology. The specific name, glaciaris, refers to the Perito Moreno Glacier, visible from the discovery site.[1]

The holotype specimen, MACN-PV 18644 and MPM 21542, was found in a layer of the lower Chorrillo Formation that dates from the Campanian–Maastrichtian. It consists of a partial skeleton without a skull, comprising a third cervical vertebra (the MACN-PV 18644 specimen found by Bonaparte in 1981), caudal vertebrae, a cervical rib, dorsal ribs, a left scapula, the ends of a right femur, and a right tibia, fibula, and astragalus. These bones were found scattered but were believed to represent one individual.[1]

Additionally, various specimens were referred to the species. MPM 21545 is an incomplete skeleton including a humerus, rib, and vertebra. It was found 100 meters from the holotype and higher on the slope, so it likely derives from another individual smaller than the type specimen. MPM 21546 consists of a separate distal caudal vertebra. MPM 21547 consists of a series of five middle caudal vertebrae found in a different location. These have not yet been excavated. MPM 21548 consists of a left tibia. A few meters away lay specimen MPM 21549, a front to middle caudal vertebra. Titanosaur eggshells and sauropod teeth have also been found in the formation. The fossils are part of the collection Museo Regional Padre Molina, with the exception of the original cervical vertebra, which is kept in the Museo Argentino de Ciencias Naturales "Bernardino Rivadavia".[1]

Description

Size and distinctive features

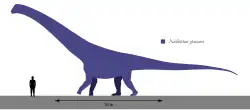

Nullotitan is a large sauropod. The holotype specimen belongs to an animal more than 20 metres (66 ft) in length.[1] This places Nullotitan in the "medium body size" class of González Riga et al. (2022), comprising sauropods with an estimated body length between 12–22 metres (39–72 ft).[2]

Novas and colleagues (2019) identified several distinguishing features, including two autapomorphies (unique derived characters). The anterior and middle caudal vertebrae are laterally and ventrally excavated by large depressions. Viewed from the front or back, the fibula has a notable sigmoid curvature. In addition, there is a unique combination of characteristics that are not unique in themselves. The vertebral centra of the anterior caudal vertebrae are remarkably short, twice as wide as long. The middle caudal vertebrae have a large fossa on the side below the transverse process. The tail vertebrae lack pneumatization. The middle caual vertebrae have a deep longitudinal furrow on the underside between two thick ridges. The lower end of the tibia is flattened from the front to the rear and widened more across than in other titanosaurs.[1]

Skeleton

The cervical vertebra of the holotype is elongated with a length of 45 centimetres (18 in) and rather low with a height of 22 centimetres (8.7 in), apart from the broken neural arch. The side is pierced by a large oval pleurocoel. The bottom is flat. The bone has many small air chambers internally, known as camellae.[1]

The anterior caudal vertebrae have an oval anterior facet. The sides slope down steeply. The transverse processes are high and flattened from front to back. The first caudal vertebra is approximately 25 cm (9.8 in) long and 40 cm (16 in) wide. The hollows on the sides are randomly distributed, separated by ridges. They are elongated and run lengthwise. The middle caudal centra are square in side view, have a convex cotyle at the back, a deep longitudinal furrow on the underside, numerous but shallower recesses, and short conical side protrusions placed at the middle height. The M. caudofemoralis, the large retractor muscle that pulls the femur backwards, continued to the sixteenth vertebra. The distal tail vertebrae are elongated and flattened, with a conical cotyle.[1]

The scapula has a bump on the inside, above the level of the acromial process, close to the front and top edges. On the inside, there is also a protrusion on the bottom edge. The humerus of MPM 21545 is 114 centimetres (3.74 ft) long. It is relatively slim, with a robustness index (RI)[nb 1] of 0.28. The deltopectoral crest is relatively short, with the lower edge at a quarter of the shaft length measured from above, a basal titanosaur characteristic.[1]

The femur has lower condyles that are about the same size. The lower shaft is strongly flattened from front to back, up to 10 centimetres (3.9 in). The tibia of the holotype is 105 centimetres (3.44 ft) long. It is robust and very wide at the bottom. The fibula is 109 centimetres (3.58 ft) long. It is robust with an RI of 0.4 and a shaft that bows outwards. The ends are strongly widened from front to back. The upper surface runs horizontally.[1]

Classification

Novas et al. (2019) identified Nullotitan as a colossosaurian titanosaur in 2019. However, they did not perform a phylogenetic analysis to test these affinities.[1]

In their 2021 publication on the titanosaur Pellegrinisaurus, Cerda and colleagues included Nullotitan in a phylogenetic analysis for the first time, using a modified version of the phylogenetic matrix of Gallina et al. (2021).[3] The researchers ran two analyses to test the relationships of titanosaurs, both of which pruned (excluded) Nemegtosaurus. The first (shown in the cladogram below as Topology A), also pruning Tapuiasaurus, was an equally weighted analysis. This placed Nullotitan as the sister taxon to Pellegrinisaurus in a clade also including Alamosaurus and Baurutitan. The second (shown below as Topology B), including Tapuiasaurus, was an implied weighted analysis, yielding full resolution in the tree. This instead placed Trigonosaurus as the sister taxon to Pellegrinisaurus (rather than within the Saltasauridae as in the prior analysis), and placed Nullotitan instead outside of this clade and the Saltasauridae, in a slightly more basal position. In both versions of the analysis, Nullotitan was recovered as a lithostrotian titanosaur, outside of the Colossosauria.[4]

| Topology A: Equal weights analysis (- Tapuiasaurus)

|

Topology B: Implied weights analysis

|

Paleoecology

Nullotitan is known from the Maastrichtian-aged Chorrillo Formation of southern Argentina. Other named dinosaurs known from the formation include the elasmarian ornithopod Isasicursor,[1] the megaraptorid theropod Maip,[5] and the birds Kookne and Yatenavis.[6] Indeterminate remains belonging to parankylosaurs,[7] euiguanodontians, hadrosaurids, noasaurids, and unenlagiids have also been recovered from the formation. Fossils of indeterminate anurans (frogs), fish, mammals, mosasaurs, snakes, turtles, and gastropods are also known.[8]

Notes

- ^ The robustness index is calculated by dividing the lower width of the bone by its length.

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Novas, F.; Agnolin, F.; Rozadilla, S.; Aranciaga-Rolando, A.; Brissón-Eli, F.; Motta, M.; Cerroni, M.; Ezcurra, M.; Martinelli, A.; D'Angelo, J.; Álvarez-Herrera, J.; Gentil, A.; Bogan, S.; Chimento, N.; García-Marsà, J.; Lo Coco, G.; Miquel, S.; Brito, F.; Vera, E.; Loinaze, V.; Fernandez, M.; Salgado, L. (2019). "Paleontological discoveries in the Chorrillo Formation (upper Campanian-lower Maastrichtian, Upper Cretaceous), Santa Cruz Province, Patagonia, Argentina". Revista del Museo Argentino de Ciencias Naturales. 21 (2): 217–293. doi:10.22179/REVMACN.21.655. hdl:11336/122229.

- ^ González Riga, Bernardo J.; Casal, Gabriel A.; Fiorillo, Anthony R.; Ortiz David, Leonardo D. (2022). "Taphonomy: Overview and New Perspectives Related to the Paleobiology of Giants". In Otero, Alejandro; Carballido, José L.; Pol, Diego (eds.). South American Sauropodomorph Dinosaurs. Springer Earth System Sciences. Cham: Springer International Publishing. pp. 541–582. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-95959-3_15. ISBN 978-3-030-95958-6.

- ^ Gallina, P. A.; Canale, J. I.; Carballido, J. L. (2021). "The Earliest Known Titanosaur Sauropod Dinosaur". Ameghiniana. 58 (1): 35–51. Bibcode:2021Amegh..58..376G. doi:10.5710/AMGH.20.08.2020.3376.

- ^ Cerda I, Zurriaguz VL, Carballido JL, González R, Salgado L (2021). "Osteology, paleohistology and phylogenetic relationships of Pellegrinisaurus powelli (Dinosauria: Sauropoda) from the Upper Cretaceous of Argentinean Patagonia". Cretaceous Research. 128: 104957. Bibcode:2021CrRes.12804957C. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2021.104957.

- ^ Rolando, Alexis M. A.; Motta, Matias J.; Agnolín, Federico L.; Manabe, Makoto; Tsuihiji, Takanobu; Novas, Fernando E. (April 26, 2022). "A large Megaraptoridae (Theropoda: Coelurosauria) from Upper Cretaceous (Maastrichtian) of Patagonia, Argentina". Scientific Reports. 12 (1) 6318. Bibcode:2022NatSR..12.6318A. doi:10.1038/s41598-022-09272-z. PMC 9042913. PMID 35474310.

- ^ Herrera, Gerardo Álvarez; Agnolín, Federico; Rozadilla, Sebastián; Lo Coco, Gastón E.; Manabe, Makoto; Tsuihiji, Takanobu; Novas, Fernando E. (April 2023). "New enantiornithine bird from the uppermost Cretaceous (Maastrichtian) of southern Patagonia, Argentina". Cretaceous Research. 144: 105452. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2022.105452.

- ^ Perez Loinaze, Valeria S.; Vera, Ezequiel I.; Raigemborn, M. Sol; Moyano-Paz, Damián; Santamarina, Patricio; Agnolín, Federico; Manabe, Makoto; Tsuihiji, Takanobu; Novas, Fernando E. (2025-01-25). "Palynofloras from the Maastrichtian Chorrillo Formation (Patagonia, Argentina): Paleoenvironmental and paleoclimatic implications". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 662 (in press) 112764. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2025.112764. ISSN 0031-0182.

- ^ Rozadilla, Sebastián; Agnolín, Federico; Manabe, Makoto; Tsuihiji, Takanobu; Novas, Fernando E. (September 1, 2021). "Ornithischian remains from the Chorrillo Formation (Upper Cretaceous), southern Patagonia, Argentina, and their implications on ornithischian paleobiogeography in the Southern Hemisphere". Cretaceous Research. 125 104881. Bibcode:2021CrRes.12504881R. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2021.104881. ISSN 0195-6671.