Nuerland

Nuerland Ro̱l Naath | |

|---|---|

| |

| Largest city | Bentiu |

| Recognised national languages | Nuer language (Thok Naath) |

| Religion | Christianity (syncretistic or otherwise), Nuer religion |

| Demonym(s) | Nuer people |

| Area | |

• Total | 98,419.5482 km2 (38,000.0000 sq mi) |

| Population | |

• Estimate | 4.5 million |

| Today part of | part of South Sudan and Ethiopia |

Nuerland (Thok Naath: Ro̱l Naath, Arabic:بلد النوير, Nickname: the True Savannah) is the indigenous homeland and traditional territory of the Nuer people,[1][2] located largely within South Sudan between latitudes 7° and 10° north and longitudes 29° and 32° east. The region covers parts of Upper Nile State, Jonglei State, Unity State, and surrounding areas, and is characterized by swamps, savannahs, and higher ground.

The Nuer are a Nilotic ethnic group primarily engaged in pastoralism, with cattle playing a central role in their economy, social organisation, and cultural practices. The seasonal flooding of Nuerland influences the community's semi-nomadic lifestyle, as people move between higher ground and swampy areas according to the dry and wet seasons.

Historically, the Nuer have had complex relations with neighbouring ethnic groups, including the Dinka and Shilluk, as well as with colonial authorities. These interactions were often marked by conflict and competition over resources.

History

In the early 19th century, the Nuer people undertook migrations and territorial expansions, often recorded in the form of raids and the displacement of neighbouring Dinka and Anyuak communities.[3]: 1

By the early 1800s, the Nuer occupied a territory of about 8,700 square miles (23,000 km²) in the Western Nile region, in present-day Bul, Leek, Western Jikany, Jagei, and Dok areas, west of the White Nile and north of latitude 7°52' N. This area was largely surrounded by Dinka communities.[3]: 23 By 1890, Nuer expansion had extended into the Eastern Nile basin, cutting through central Dinka territory and reaching a substantial portion of Anyuak land near the Ethiopian escarpment.[4][5]

Between 1820 and 1880, the Nuer expanded their territory to approximately 35,000 square miles (91,000 km2).[3]: 1 This rapid territorial growth was influenced by external factors, including the territorial campaigns of Abyssinia and the Ottoman Empire's invasions of northern Sudan in 1821 and 1827, which eventually curtailed further Nuer expansion.[6]

Two major migration waves characterised Nuer expansion in the 19th century. The first was led by Latjor, who guided the Jikany Nuer, and the second by Bidiet, who led the Lou Nuer. Neither man held political or ritual authority, but both were renowned warriors noted for their leadership and ability to inspire youth for raids.[7]

The Jikany migration began northward toward Jebel El Liri on the Nuba border, then eastward along the Nuba–Shilluk frontier. After defeating Reth Awin, king of the Shilluk, the Jikany moved through Shilluk territory near Melut, crossing the Nile during the dry season into northern Dinka lands. Following battles in which they captured cattle, they turned southward to the lower Sobat River, temporarily settling in Abwong before pushing upstream along both sides of the Sobat into their present territory.[3]

The Lou Nuer and Gawaar spearheaded the second wave of expansion, described as the "twin migration." The Lou moved eastward into central Dinka territory, extending as far as the eastern Jikany border. The Gawaar, originally in southern Dok territory, crossed the Nile and settled in the Sudd swamps. Around the same period, Lou Nuer moved eastward while Lak and Thiang Nuer migrated north of Zeraf Island, which had earlier been taken by the Lou. Although these movements were independent, together they significantly reshaped the eastern Nuer presence.[3]: 33

Between 1845 and 1876, the Nyuong Nuer advanced southward along the west bank of the Nile, displacing Shilluk and pushing the Shilluk Dinka further south. This marked the end of western Nuer expansion across the White Nile. On the eastern bank, however, territorial expansion continued well into the 20th and early 21st centuries. Attempts by western Nuer groups to expand further westward and northward were largely unsuccessful, partly because large portions of their homeland had already been vacated by groups migrating eastward.[3][8]

Colonial records from 1905 to 1928 note at least 26 Nuer raids against the Dinka, describing widespread devastation and outlining Nuer military organisation, tactics, and strategies. Expansion during this period often occurred through the occupation of lands vacated by Dinka after recurrent raids, as well as through the assimilation of Dinka groups into Nuer society. Much of the territory gained during the 19th century had previously been inhabited by the Dinka and Anyuak.[3]

Archaeological evidence suggests that the Nuer have lived in the Nile Valley region since at least 3372 BCE.[9]

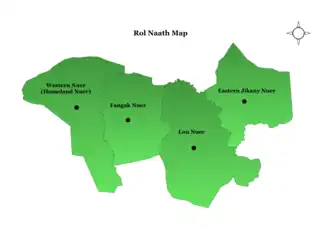

These expansions led to the division of the Nuer into three major groupings:

- Western Nuer (Homeland Nuer): Bul, Leek, Western Jikany, Jagei, Dok, Nyuong, Haak

- Central Nuer: Fangak Nuer (Lak, Thiang, Gawaar) and Lou Nuer (Guun, Mor)

- Eastern Nuer: Eastern Jikany (Gajiok, Gajaak, Gagaang)[3]

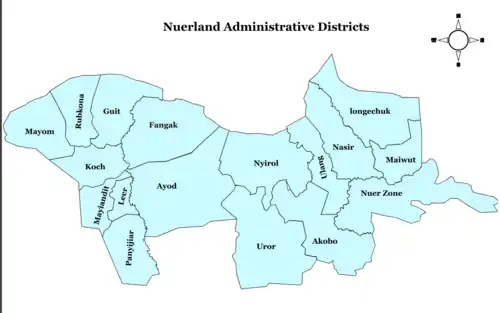

Nuerland counties

Nuerland is located largely within South Sudan, with portions extending into western Ethiopia.[10][11] The region covers an estimated 38,000 square miles (98,420 km²).[11] It includes the Sudd, one of the largest swamp regions in the world.[12] The White Nile divides the Nuer into two sections: the western part (often referred to as the Nuer homeland) and the eastern part (Central and Eastern Nuer).[13] The landscape is dominated by open savannah, thornwood forests, and extensive marshlands, a geography that contributed to the nickname the True Savannah.[14]

Nuerland is bordered by the Dinka to the west and south, the Shilluk and Dinka to the north, the Burun to the northeast, the Anyuak and Ethiopia to the east, and the Murle to the southeast.[4] The terrain is largely flat and subject to heavy rainfall during the wet season, when rivers flood and tall grasses cover much of the area. During the dry season, when rainfall ceases and rivers recede, the land is prone to drought.[14][15]

Nuerland constitutes 16 of the 79 counties of South Sudan and 7 of the 13 woredas (districts) of Gambella Region in Ethiopia. Within South Sudan, the Nuer counties are distributed across the Greater Upper Nile region: four in Upper Nile State, five in Jonglei State, and seven in Unity State. In Ethiopia, five woredas form the Nuer Zone of Gambella, while two are shared with the Anyuak and Ethiopian highland communities.[16]

| County | Payam |

|---|---|

| Nasir/Kuanylualthuan | Nasir (county headquarters), Dhorading, Dinkar, Kech Kun, Gai Reang, Roam, Koat, Kierwan, Jikmir, Kuetrengke, Wanding, Mandeng, Mading, Maker, Gurnyang, Wechnyot[17][18] |

| Ulang | Ulang (county headquarters), Doma, Yomding, Kurmuot, Nyangore, Ying, Barmach, Kerchot, Torbaar, Riek-Kueh[19] |

| Longechuk | Mathiang (county headquarters), Dajo, Guelguk, Jangok, Malual, Pamach, Wudier[20] |

| Maiwut | Maiwut (county headquarters), Kigile, Jekow, Jotoma, Uleng, Pagak, Wuor, Malek, Turuu[21] |

| Fangak | Old Fangak (county headquarters), Phom/New Fangak, Paguir, Manajang, Mareang[22][23] |

| Ayod | Ayod (county headquarters), Kurwai, Mogok, Kuach-deng, Wau, Pagil, Pajiek[24] |

| Uror | Yuai (county headquarters), Puolchoul, Tiam, Karam, Pamai, Motot, Pathai, Payai, Pieri[25][26] |

| Nyirol | Waat (county headquarters), Thol, Chuil, Nyambor, Pulturuk, Pading[27][28] |

| Akobo | Bilkey (county headquarters), Allali, Buong, Kuonykew, Walgak, Deng Jok, Diror, Nyandit[29][30] |

| Mayom | Mayom (county headquarters), Bieh, Wangkei, Kuerbuone, Mankien, Kueryiek, Ngop, Pup, Riak, Ruathnyibuol, Wangbuor-1, Wangbuor-2, Wangbuor-3[31] |

| Rubkona | Rubkona (county headquarters), Dhorbor, Bentiu, Budaang, Wathjaak, Kaljak, Ngop, Nhialdiu, Panhiany[32][33] |

| Guit | Guit (county headquarters), Wathnyona, Kedad, Nyathoar, Kuac, Kuerguini, Niemni, Bil, Nying[34] |

| Koch | Kuachlual (county headquarters), Boaw, Pakur, Ngony, Gany, Jaak, Norbor[35][36] |

| Mayiandit | Mayiandit (county headquarters), Tutnyang, Dablual, Thaker, Leah, Maal, Pabuong, Tharjiathbor, Rubkuay, Bhor, Jaguar, Madol 1, Madol 2, Mirnyal[37][38] |

| Leer | Leer (county headquarters), Bou, Thonyor, Guat, Juong Kang, Padeah, Pilieny, Yang[39] |

| Panyijiar | Panyijiar (county headquarters), Ganyiel, Kol, Mayom, Nyal, Pachaar, Pachak, Pachienjok, Thoarnhoum, Tiap[40] |

| County(Woreda) | Payam |

|---|---|

| Jokow Woreda | |

| Lare Woreda | |

| Akobo Woreda | |

| Wanthoa Woreda | |

| Makuey Woreda | |

| Gambella Zuria (shared with Anyuak)[41] | |

| Itang Special Woreda (shared with Anyuak)[42] |

Vegetation and climate

The climate of Nuerland is generally tropical, characterised by two main seasons: a wet season and a dry season. While these two seasons primarily define the climate, local terminology also recognises four seasonal phases—summer, spring, autumn, and winter—that influence agricultural and pastoral activities.

The vegetation of Nuerland consists mainly of grassland savannah, woodland savannah, and forested areas. Common tree species include acacia (a major source of gum arabic), lalob lalob (desert date), tamarind (noted for its sour fruit), neem, baobab, and palm trees, along with several native plant species. These ecosystems of grassland, woodland, and forest provide natural habitats for wildlife such as elephants, giraffes, lions, leopards, buffalo, hyenas, foxes, servals, monkeys, rhinoceroses, and various antelope species, particularly gazelles.

The ecosystem of Nuerland is further defined by rivers, marshes, extensive swamps, and numerous fishing ponds. These environments support a wide range of invertebrates, fish, amphibians, waterfowl, and other forms of flora and fauna.

Geomorphologically, Nuerland is characterised by expansive flat savannah dominated by loam soil, with smaller areas of clay, silt, and sandy soil. These physical features make the region one of the agriculturally fertile areas of East Africa.[43]

Livestock and agriculture

The economy of Nuerland is primarily based on agriculture, animal husbandry, fishing, and hunting. The Nuer are generally regarded as a pastoral people with a strong emphasis on livestock, though cultivation also plays an important role.[3] During the dry season, many Nuer communities migrate to cattle and fishing camps in swampy areas, near rivers, and around fishing ponds. At the end of the dry season, they return to their villages to cultivate crops. The principal crops include maize, millet, and sorghum, followed by beans, pumpkin, okra, and tobacco.[4]

Livestock—particularly cattle, goats, and sheep—play a central role in Nuer society. Cattle, especially oxen, hold physical, economic, social, and spiritual significance. They serve as a primary measure of wealth, a source of bride wealth, and a central feature in rituals and cultural practices. Nuer men traditionally develop close attachments to their oxen, often recognising individual animals by their habits and physical characteristics. Oxen may be decorated, sung about in songs, and given symbolic value within the community.[3]

Although cattle form the largest share of livestock, sheep and goats also hold value. Livestock are not generally raised for meat, but bulls and sheep are occasionally slaughtered for important social or ritual occasions.[44][45]

Resources

Nuerland is rich in natural resources and has played a central role in the economy of South Sudan since the country's independence. These resources include oil, untapped natural gas, water resources, wildlife, and fisheries.

Oil, primarily extracted in the western Nuer homeland, has been a cornerstone of South Sudan's economy, accounting for approximately 80% of the country's annual revenue since its discovery in 1978 by Chevron.[46]

Despite extensive war-related destruction and underdevelopment, Nuerland continues to contribute more than 80% of South Sudan's overall economic output.[47]

Gallery

-

Nuer man and his ox.

Nuer man and his ox. -

Ngundeng Pyramid located in Wech Deng village, Nyirol County 1901.

Ngundeng Pyramid located in Wech Deng village, Nyirol County 1901.

References

- ^ Jek, Bol J. (2018-11-04). The Nuer State: Röl Nath. Uganda National Library. ISBN 978-9970-9711-2-1.

- ^ "AFRICA | 101 Last Tribes - Nuer people". www.101lasttribes.com. Retrieved 2024-06-12.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Kelly, Raymond C. (1985-08-30). The Nuer Conquest: The Structure and Development of an Expansionist System. Ann Arbor, Mich: University of Michigan Press. ISBN 978-0-472-08056-4.

- ^ a b c Evans-Pritchard, E. E. (1940-01-01). The Nuer: A Description of the Modes of Livelihood and Political Institutions of a Nilotic People. Pantianos Classics. ISBN 978-1-78987-318-4.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ^ People, Nuer. "Nuer People of South Sudan". study.com. Retrieved 2024-06-12.

- ^ Johnson, Douglas H. (1997-05-01). Nuer Prophets: A History of Prophecy from the Upper Nile in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries (Revised ed.). Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-0-19-823367-1.

- ^ "Sudan Notes and Records Volume 32 — Sudan Open Archive". sudanarchive.net. Retrieved 2024-06-08.

- ^ Jock, George Gatluak. The Unique Background of the Nuer Nation.

- ^ "The Nuer People of South Sudan | Language, Facts & Traditions". study.com. Retrieved 2024-06-07.

- ^ "eHRAF World Cultures". ehrafworldcultures.yale.edu. Retrieved 2024-06-12.

- ^ a b "Nuer | Encyclopedia.com". www.encyclopedia.com. Retrieved 2024-06-12.

- ^ Jek, Bol Jok; D, Deng Vanang (2021-02-04). THE HISTORY OF NUER NATION 5000 BCE TO 1943: CAALLI ROLNATH. Independently published. ISBN 979-8-7047-1161-2.

- ^ Beswick, Stephanie (2004). Sudan's Blood Memory: The Legacy of War, Ethnicity, and Slavery in Early South Sudan. University Rochester Press. ISBN 978-1-58046-151-1.

- ^ a b "Sudan Notes and Records Volume 21 — Sudan Open Archive". sudanarchive.net. Retrieved 2024-06-08.

- ^ Huffman, Ray; Westermann, D. (1931). Nuer customs and folklore. International Institute of African Language and Culture.

- ^ "Zones and Woredas". Gambella Vision. Retrieved 2024-06-25.

- ^ "Luakpiny/Nasir". csrf-southsudan. 17 April 2020. Retrieved 2024-06-16.

- ^ "UNMISS skills communities in Nasir on improving relations with uniformed personnel". UNMISS. 2024-05-15. Retrieved 2024-06-16.

- ^ "Ulang". csrf-southsudan. 21 April 2020. Retrieved 2024-06-16.

- ^ "Longochuk". csrf-southsudan. 14 April 2020. Retrieved 2024-06-16.

- ^ "Maiwut". csrf-southsudan. 21 April 2020. Retrieved 2024-06-16.

- ^ "Fangak". csrf-southsudan. 31 March 2020. Retrieved 2024-06-16.

- ^ "South Sudan Fangak County reference map (As of March 2020) - South Sudan | ReliefWeb". reliefweb.int. 2020-03-30. Retrieved 2024-06-16.

- ^ "Ayod". csrf-southsudan. 18 March 2020. Retrieved 2024-06-16.

- ^ "Uror". csrf-southsudan. 31 March 2020. Retrieved 2024-06-16.

- ^ "South Sudan Uror County reference map (As of March 2020) - South Sudan | ReliefWeb". reliefweb.int. 2020-03-30. Retrieved 2024-06-16.

- ^ "Nyirol". csrf-southsudan. 31 March 2020. Retrieved 2024-06-16.

- ^ "South Sudan Nyirol County reference map (As of March 2020) - South Sudan | ReliefWeb". reliefweb.int. 2020-03-30. Retrieved 2024-06-16.

- ^ "Akobo". csrf-southsudan. 18 March 2020. Retrieved 2024-06-16.

- ^ "South Sudan Akobo County reference map (As of March 2020) - South Sudan | ReliefWeb". reliefweb.int. 2020-03-30. Retrieved 2024-06-16.

- ^ "Mayom". csrf-southsudan. 14 April 2020. Retrieved 2024-06-16.

- ^ "Rubkona". csrf-southsudan. 14 April 2020. Retrieved 2024-06-16.

- ^ "South Sudan: Rubkona County reference map (As of March 2020) - South Sudan | ReliefWeb". reliefweb.int. 2020-03-31. Retrieved 2024-06-16.

- ^ "Guit". csrf-southsudan. 14 April 2020. Retrieved 2024-06-16.

- ^ "Koch". csrf-southsudan. 14 April 2020. Retrieved 2024-06-16.

- ^ "South Sudan: Koch County reference map (As of March 2020) - South Sudan | ReliefWeb". reliefweb.int. 2020-03-31. Retrieved 2024-06-16.

- ^ "Mayendit". csrf-southsudan. 14 April 2020. Retrieved 2024-06-16.

- ^ "South Sudan Mayendit County reference map (As of March 2020) - South Sudan | ReliefWeb". reliefweb.int. 2020-03-30. Retrieved 2024-06-16.

- ^ "Leer". csrf-southsudan. 14 April 2020. Retrieved 2024-06-16.

- ^ "Panyijiar". csrf-southsudan. 14 April 2020. Retrieved 2024-06-16.

- ^ GCDC (2016-08-22). "Gambella Profile". gambellacommunity.org. Retrieved 2024-06-15.

- ^ "Zones and Woredas". Gambella Vision. Retrieved 2024-06-15.

- ^ Jock, George Gatluak (2019-04-09). The Unique Background of the Nuer Nation. Independently published. ISBN 978-1-0929-9885-7.

- ^ "Nuer Dilemmas: Coping With Money, War, And The State (2023 Edition) | Mystery to Me : An Independent Bookstore". www.mysterytomebooks.com. Retrieved 2024-06-06.

- ^ Hutchinson, Sharon (May 1992). "the cattle of money and the cattle of girls among the Nuer, 1930–83". American Ethnologist. 19 (2): 294–316. doi:10.1525/ae.1992.19.2.02a00060. ISSN 0094-0496.

- ^ "Block 5A - Oil field of Sudan - Massive changes". www.prinsengineering.com. Retrieved 2024-06-06.

- ^ "Austrian OMV to acquire interest Block 5A in Sudan — Alexander's Gas and Oil Connections". 2012-03-23. Archived from the original on 2012-03-23. Retrieved 2024-06-06.