Nynetjer

| Nynetjer | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ninetjer, Ninuter, Nyneter, Neteren, Banetjer, Banetjeren, Banetjeru, Binōthris, Biophis, Netjermu | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

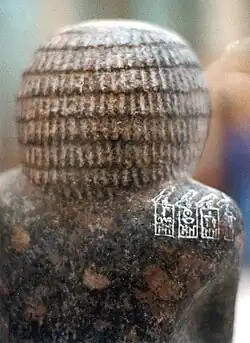

Quartzite[note 1] statue of Nynetjer wearing ceremonial clothes of the Sed festival,[3][4] Rijksmuseum van Oudheden | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Pharaoh | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Reign | Duration: 35–49 years, most probably 40, sometime in the 29th century BC to early 27th century BC[note 2] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Predecessor | Raneb | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Successor | uncertain: Wadjenes[12], Nubnefer,[13] Weneg (if distinct from Raneb) or Seth-Peribsen[14] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Burial | Gallery Tomb B, Saqqara | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Dynasty | Second dynasty | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Nynetjer (also known as Ninetjer and Banetjer) was the third pharaoh of the second dynasty of Egypt during the Early Dynastic Period. The dates for his reign are uncertain, Egyptologists have proposed that it took place at some point between the late 29th and the early 27th century BC for 35 to 49 years, and most likely lasted around 40 years. Archaeologically, Nynetjer is the best-attested king of the early second dynasty and he is also recorded on several king lists dating to the Old Kingdom and the later Ramesside and Ptolemaic periods. Direct evidence shows that he succeeded Raneb on the throne. The events at the end of his reign and the identity of his successor are much less clear. Both historical sources and archaeological evidence points to some breakdown or partition of the state along both religious and political lines, likely seeing concurrent rulers reigning over Upper and Lower Egypt until the country was reunited by Khasekhemwy at the end of the dynasty.

Most of the events recorded for Nynetjer's reign on the Old Kingdom royal annals are regular religious festivals and censuses undertaken for taxation purposes. The likely locations for these events indicate that royal activity was largely confined to the capital Memphis and its vicinity in Lower Egypt, with the possible exception of a military campaign in Nubia. The administrative structure of the state continued on its first dynasty (c. 3150 – 3000 BC) basis but became more sophisticated, with the earliest evidence for the nome regional management system dating to Nynetjer's reign.

Nynetjer had a large gallery tomb dug for himself in Saqqara, now below parts of both Djoser's and Unas's pyramid complexes. His tomb comprises a maze of over 150 rooms, some of which are arranged to model a royal palace. Although used as a necropolis during Egypt's later periods, the tomb still housed some of the original funerary equipment of the king. This included hundreds of jars that once held wine, beer and jujube fruits. Excavations have also produced numerous stone tools, some of which seem to have been used in a ritual feast for Nynetjer's burial. The subterranean tomb was likely built with associated superstructures but these have not survived as they were levelled and overbuilt by subsequent pharaohs.

Chronology and identity

Attestations

Archaeologically, Nynetjer is the best attested of the kings of the early second dynasty.[19] His name appears in inscriptions on numerous stone vessels and clay sealings from his tomb at Saqqara.[1] A large number of alabaster vessels and earthen jars with black ink inscriptions bearing his name were also found in the tomb of Seth-Peribsen at Abydos and in the galleries beneath the step pyramid of king Djoser.[20] Further attestations include a small ivory vessel from Saqqara[21] and sealings bearing his name from the tombs of three elite individuals in North Saqqara.[22][23] Additional sealings were uncovered in a mastaba in Giza[24] and in a tomb in Helwan.[25][19]

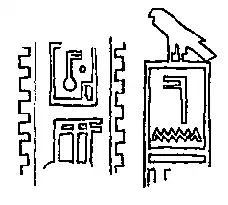

Nynetjer's name also appears on a rock inscription near Abu Handal in Lower Nubia which shows a serekh of the king. A serekh is a rectangular symbol enclosing a royal name and representing the façade of a palace surmounted by the Horus falcon. It is the oldest form of royal titulary from ancient Egypt. In this case the serekh only encloses a "N" sign but with the sign "Netjer" for "God" placed above the serekh in the position normally occupied by the Horus falcon. Consequently Nynetjer's name is rendered as "The God N". The absence of Horus may hint at religious disturbances as suggested by the later choices of Seth-Peribsen to have Set instead of Horus above his serekhs and of pharaoh Khasekhemwy, final ruler of the dynasty, to have both gods facing each other above his.[26]

Relative chronology

Most Egyptologists agree on the relative chronological position of Nynetjer as the third ruler of the early second dynasty and successor of Raneb.[note 3] This is directly attested by the contemporary statue of Hetepedief. The statue, uncovered in Memphis and made of speckled red granite, is one of the earliest example of private Egyptian sculpture. Hetepedief was priest of the mortuary cults of the first three kings of the dynasty, whose serekhs are inscribed in seemingly chronological order on Hetepedief's right shoulder: Hotepsekhemwy, Raneb then, Nynetjer.[33][34][35] Further archaeological evidence supports this theory such as stone bowls of Hotepsekhemwy and Raneb reinscribed during Nynetjer's rule.[36][37]

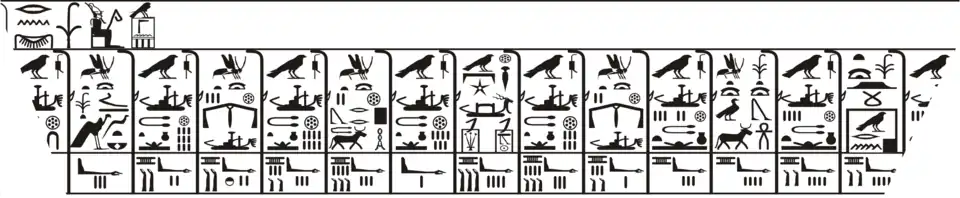

Several historical sources also point to the same conclusion. The oldest of these is the Old Kingdom royal annals now known after the name of its largest surviving fragment, the Palermo Stone. These annals were likely first compiled during the early fifth dynasty, possibly under Neferirkare Kakai (mid-25th century BC) around whose reign the record stops.[38][39] These annals are considered to be a reliable witness to Nynetjer's rule in particular because, as Wilkinson puts it, they correctly give his name "in contrast to the corrupt, garbled variants found in later king lists".[40] While the Palermo stone does not preserve the identity of Nynetjer's immediate predecessors, it is consistent with him not being the first king of the dynasty. This source also presents an additional name for Nynetjer: Ren-nebu, meaning "golden offspring" or "golden calf". This name was also found on artefacts dating to Nynetjer's lifetime and Egyptologists including Wolfgang Helck and Toby Wilkinson think that it could be some kind of forerunner of the golden-Horus-name that was established in the royal titulature at the beginning of third dynasty under Djoser.[41] The second-oldest historical source on Nynetjer is the Turin canon, a list of kings written under Ramses II (c. 1303 – 1213 BC). It ranks him under the name Netjer-ren as the third king of his dynasty after Hotepsekhemwy and Raneb.[42] Two more sources of the Ramesside era present similar informations: the Abydos King List gives a Banetjer as the third kind of the second dynasty,[43] while the Saqqara table lists Banetjeru at the same position.[44] Both Banetjer and Banetjeru are understood to be corrupt forms of Nynetjer's ancient name.[12]

The latest ancient historical source on Nynetjer's reign is the Aegyptiaca, Ptolemy II (283 – 246 BC) by Manetho. No copies of the Aegyptiaca have survived and it is now known only through later writings by Sextus Julius Africanus (c. 160 – 240) and Eusebius (c. 260/265 – 339). According to the Byzantine scholar George Syncellus (fl. 800), Africanus and Eusebius wrote that the Aegyptiaca recorded "Binōthris"[note 4] or "Biophis"[note 5] as the third king of the second dynasty,[45] Binōthris likely being the Hellenized form of Banetjer, the name used for Nynetjer during the Ramesside era.[46]

Reign duration

The duration of Nynetjer's rule may be appraised from several historical sources. The surviving fragments of the Old Kingdom royal annals record the main events and Nile flood levels from what is likely the fifth or sixth year of Nynetjer's reign until the 21st.[19] The remainder of the records concerning his rule are lost. Nonetheless, given the space afforded for each year on the annals and the position of subsequent reigns reconstructions have been attempted from the surviving fragments to estimate the total of Nynetjer's years on the throne. With a single exception,[note 6] all the Egyptologists who studied this problem have proposed long reigns[note 7] lasting between 38 years[12] and up to 49 years.[47] The most recent reconstruction of the royal annals by Wilkinson in 2000 concludes that Nynetjer's record on the Palermo stone was most probably of 40 complete or partial years.[49][50] Two additional historical sources record a reign length for Nynetjer: firstly, the Turin Canon gives him 96 years of rule,[51] which is universally rejected by modern Egyptologists. Secondly, in Africanus's version of the Aegyptiaca the king Binōthris—as Nynetjer was most probably known in Greek—is credited with 47 years of reign.[45]

Archaeological evidence favors a long reign too. A seated statuette of Nynetjer shows him wearing the ceremonial tight-fitting vestment of the Sed festival, a feast for the rejuvenation of the king that came to be celebrated for the first time only after the king had reigned for 30 years.[10] This statuette is the earliest known representation in the round of a well-identified Egyptian king.[1] That Nynetjer celebrated a Sed festival is further supported by the large quantity of stone vessels bearing Nynetjer's name that were unearthed in the galleries beneath Djoser's step pyramid which were likely made in connection with the Sed festival.[1]

Reign

Events

The Palermo stone mostly records standard rituals performed by the king, in particular the biennial Following of Horus connected to taxation, and regular religious festivals.[52] These included cults to the god Sokar every six years, the running of the Apis bull and an "adoration of the celestial Horus".[53] Although not mentioned in the royal annals, the goddesses Bastet and Neith must also have received cults as witnessed by stone bowls on which their names are associated Nynetjer's.[54][55] Another bowl bearing the king's name mentions a chapel of Hedjet, the white crown of Upper Egypt, possibly set up in Memphis,[56][57] then likely the capital of Egypt.[58] All of these activities took place in the Memphite area except for one ritual associated to Nekhbet, goddess of Elkab.[59] Wilkinson observes that, with one exception,[26] Nynetjer is not well attested archaeologically outside of the Memphite region. This could point to royal activity being largely confined to Lower Egypt during his reign.[60][50] The inscription bearing Nynetjer's name found in Nubia could point to an exception to this observation, as it may be a clue that he sent a military expedition into this region. Given that the expedition is not mentioned in the surviving fragments of the royal annals, it may have been recorded in what is now a lacuna, which would place it some time after Nynetjer's 20th year on the throne.[26]

Two special events are also recorded on the annals, namely the foundation of "Hor-ren", a temple, palace or estate during Nynetjer's seventh year of rule,[61] and the foundation or attack of two localities "Shem-Ra" and "Ha", the latter of which translates to "north land".[1] This may refer to the suppression of a rebellion in Lower Egypt.[61] Alternatively, for Reader and Jochem Kahl, this event is to be understood as part of the important development of the sun worship and the cult of Ra during the reigns of Raneb and Nynetjer.[62][63] They interpret the record as referring to the foundation of an institution or building whose name, "Shem-Ra", has been variously translated as "The going of Ra",[64] "The sun proceeds",[64] or "The sun has come". [52] For these Egyptologists as well as Grimal, the god Ra took over the role of the king's progenitor and Nynetjer's name should be understood within this context as meaning "He who belongs to the god (Ra)".[65]

A smaller fragment of the annals, the Cairo stone, may record further events belonging to Nynetjer's later reign: another festival of Sokar in his 24th year on the throne and a Following of Horus in his 34th,[1][52] although the dating is uncertain.[66] The surface of the stone slab in this section is much damaged and most of the record is illegible. Siegfried Schott has proposed reading also the "birth" (creation) of a statue of Anubis and an "Appearance of the king of Lower and Upper Egypt".[52] Among later historical sources, the Aegyptiaca reported concerning Binōthris that:

In his reign it was decided that women might hold the kingly office.[67]

For Walter Bryan Emery this comment may possibly be related to the status of queens Meritneith and Neithhotep of the first dynasty (c. 3150 – 3000 BC), both of whom are believed to have held the Egyptian throne for several years.[68][69]

Administration

The reign of Nynetjer likely witnessed an increase in the size of the civil service as the tasks for which it was responsible grew significantly.[72] For example, the biennial event "Following of Horus" referred to on the Palermo stone most probably involved a journey of the king and the royal court throughout Egypt.[73] From at least the reign of Nynetjer onwards the purpose of this journey was to undertake a census for taxation purposes, collect and distribute various commodities. According to the annals of the third dynasty (27th century BC) this census involved an enumeration of gold and land.[73] The responsibility for the supervision of state revenues was under the authority of the chancellor of the treasury of the king,[74] who directed three administrative institutions introduced by Nynetjer in replacement of an older one.[75] Nynetjer might also have introduced an office for food management related to the census.[76] At the beginning of third dynasty the "Following of Horus" disappears from the records replaced by a more thorough census, which may have originated during Nynetjer's reign.[77] From at least the reign of Sneferu (c. 2600 BC) onwards this extended census included cattle counts—under which name it became known—while oxen and small livestock were recorded from the fifth dynasty (25th-24th century BC) onwards.[74]

Ink inscriptions on jars strongly suggest that the administrative partition of Egypt into nomes existed under Nynetjer's rule, providing the earliest evidence for this regional management system.[note 8][80] Similarly, the earliest individual holding the full titles associated with the office of vizier, Menka, may have served Nynetjer.[81][82]

These innovations represent a qualitatively new stage in resource collection and management on behalf of the nascent Egyptian state after the creation in the mid first dynasty of the institutions responsible for the preparation of the royal tomb and the upkeep of subsequent funerary cults, as well as the state treasury.[72] In the early dynastic period, this treasury did not function as its modern counterparts such as the United States Department of the Treasury.[83] Rather it was an institution responsible for administering agricultural produces and stone ware, the latter being an important component of the funerary furniture. Tombs of kings of the first to third dynasties included thousands to tens of thousands of stone bowls, jars and cups. The ritualised supply of these to the royal tomb played a major role in the grand spectacle of the preparation of the king's tomb and so were a crucial element in the early ideology of kingship.[83] Archeological evidence confirms the existence of the treasury during Nynetjer's rule.[84][85][86]

The main task of the civil service was to ensure the continuing existence and effectiveness of kingship, which included providing for the king's life after death.[72] This, in turn, required increasing quantities of commodities to be regularly collected as the second-dynasty royal tombs were modelled after the king's palace, incorporating a large number of storage rooms for wine and food.[88] Goods necessary for the provision of the court and funerary cults were produced in large agricultural domains and estates dedicated to producing specific resources. Such institutions had been set up by kings since at least the first dynasty.[89] Although a single estate providing natron—a type of salt used for curing food, cleaning and in the mummification process—is known from a seal impression in connection with Nynetjer,[70][71] he likely established novel estates and domains during his reign on top of maintaining those founded prior to his rule.[90]

Positions at court and highest offices of the state were likely to have been determined on family ties and bonds of kinship,[91] as in the preceding late Predynastic Period.[92][93] Few officials serving Nynetjer are known by name. These include Iyenkhnum,[94][95][96] Ruaben the overseer of sculptors,[97] and possibly the vizier Menka.[81]

End of reign

What happened towards the end of Nynetjer's rule and shortly thereafter is very uncertain. It is possible[98] that Egypt saw civil unrest[99] and the rise of competing claimants to the throne reigning concurrently over two realms in Upper and Lower Egypt.[30][100] Historical records preserve conflicting lists of kings between the end of Nynetjer's reign and that of Khasekhemwy,[101] who oversaw military campaigns against Lower Egypt.[102] The period from Nynetjer's death until Khasekhemwy's coronation is very obscure and the understanding of it has seen little progress in Egyptology over the entire 20th century.[103] Consequently, an accurate estimate of its length is impossible,[104] the total temporal duration of second dynasty remains debated by Egyptologists and boils down educated guesses[105] of one to two centuries.[106][11][107]

Three hypotheses have been put forth concerning this period: first there could have been a political breakdown and a religious conflict;[1][10][108] second this could result from a deliberate choice on Nynetjer's behalf following administrative considerations;[109][65] or third an economic collapse might have led to Egyptian disunity.[110]

For Erik Hornung, the troubles originate from an Upper Egyptian reaction to the migration of power and royal interest towards Memphis and Lower Egypt, leading to a breakdown of the unity of the state.[108] This is manifested through he abandonment of the first-dynasty necropolis of Abydos in favor of Saqqara, which saw the construction of the tombs of the first three kings of the second dynasty.[10] An attempt to counteract this trend could explain why Hotepsekhemwy and Nynetjer maintained a chapel to the white crown of Upper Egypt in Memphis.[57] The nascent political conflict between Lower and Upper Egypt might also have taken on a religious aspect. For Grimal, the establishment of the cult of Ra by Raneb and the emphasis on Bastet and Sopdu, both Lower Egyptian deities, on Raneb and Nynetjer's behalf may have been perceived as too favourable to northern Egypt.[65] Hornung and Hermann Alexander Schlögl also point to Seth-Peribsen's choice of the god Set rather than Horus as a divine patron for his name, Set being an Upper Egyptian god from Ombos.[108] Additionally, Seth-Peribsen chose to have his tomb built in old royal burial grounds of Abydos, where he also erected a funerary enclosure.[108] At the same time, another line of kings reigned over Lower Egypt and they associated themselves with Horus.[10][108] For Wilkinson, who interprets the events of Nynetjer's 13th year on the throne as the quelling of rebellion in the North,[111] unrest had already broken out during his reign. Wilkinson points to no less than four rituals named "Appearances of the king of Lower Egypt" reported for Nynetjer on the Old Kingdom royal annals as possibly "intended to deliver a political message about the extent of his authority" over this region.[112] For Wilkinson, another indirect evidence of troubles is given by the numerous stone vessels originally prepared for Nynetjer’s Sed festival that were found in the galleries beneath Djoser's pyramid. These vessels may have remained in storage at Saqqara instead of being distributed because strife disrupted communications and weakened the authority of the central administration.[1]

Egyptologists such as Helck, Grimal, Schlögl and Francesco Tiradritti believe instead that Nynetjer left a realm that was suffering from an overly complex state administration. Consequently, Nynetjer could have decided to split Egypt between his two successors, possibly his sons, who would rule two separate kingdoms in the hope that the two rulers could better administer the states.[65][109] In this case, the division of Egypt would have been peaceful at first,[113] as possibly witnessed by the joint mortuary cults in Saqqara of two subsequent second dynasty kings Senedj and Seth-Peribsen, would might have ruled over Lower and Upper Egypt, respectively.[114]

In contrast, Egyptologists such as Barbara Bell and Michael Hoffman believe that an economic catastrophe such as a famine or a long-lasting drought could have affected Egypt around this time.[115] Therefore, to address the problem of feeding the Egyptian population, Nynetjer may have split the realm into two and his successors ruled independent states until the famine came to an end. Bell points to the inscriptions of the Palermo stone, where, in her opinion, the records of the annual Nile floods show constantly low levels during this period.[110] Bell's theory is not accepted by some Egyptologists such as Stephan Seidlmayer, who objects to Bell's calculations. For Seidlmayer the annual Nile floods were at their usual levels at Nynetjer's time up to the period of the Old Kingdom. According to him, Bell had overlooked that the heights of the Nile floods in the Palermo Stone inscriptions only takes into account the measurements of the nilometers around Memphis, but not elsewhere along the river. Any long-lasting drought is would therefore less likely to be an explanation.[116]

As Wilkinson remarks, all attempts by modern Egypotlogists at reconstructing events between the end of Nynetjer's reign and Khasekhemwy's ascent to the Upper Egyptian throne remain highly speculative owing to the lack of strong, direct evidence on the matter.[117]

Succession

The identity of Nynetjer's successor is uncertain and it is unclear whether this successor voluntarily shared his reign with another ruler, if there were rival claimants to the throne,[101] or if the Egyptian state was split later, at the time of this successor's death. All known king lists from historical sources such as the Saqqara list, the Turin Canon and the Abydos table have Wadjenes as Nynetjer's immediate successor, a king who is poorly known. These sources claim that Wadjenes was succeeded by the equally obscure Senedj. Wadjenes and Senedj may or may not be the same as Weneg[note 9] and Nubnefer, shadowy rulers who could have ruled shortly after Nynetjer too.[119][120][121][122][123] After Senedj, the kinglists differ from each other. While the Saqqara list and the Turin canon mention the kings Neferka(ra) I, Neferkasokar and Hudjefa I as immediate successors, the Abydos list skips them and lists a king Djadjay, now identified with Khasekhemwy. This may reflect two traditions, a Lower and an Upper Egyptian one, both preserving the names of distinct regional dynasties. Indeed, if Egypt was already divided when Senedj gained the throne, kings like Sekhemib-Perenmaat and Seth-Peribsen would have ruled Upper Egypt, whilst Senedj and his successors would have ruled the Memphite region in Lower Egypt.[65] Political unrest and religious division are further confirmed by archaeological evidence pertaining to Khasekhemwy, last king of the second dynasty who is believe to have reunited the country. Indeed, he started his reign in Upper Egypt under the name Khasekhem, "The powerful one has appeared", placing his serekh under the patronage of the god Set. An inscription on a stone vase records him “fighting the northern enemy within Nekheb”, indicating that an enemy was closing in on the historical seat of Upper Egyptian power. Later in his reign he added Horus to his serekh, changed his name to Khasekhemwy which means "The two powers have appeared" along with the addition "The two lords are at peace with him".[124][125]

Tomb

The tomb of Nynetjer was discovered by the Egyptian Egyptologist Selim Hassan in 1938 while he was excavating mastabas under the aegis of the Service des Antiquités de l'Egypte in the vicinity of the Pyramid of Unas.[126] A mastaba is a type of flat-roofed, rectangular structure with inward sloping sides that was common in the Early Dynastic and Old Kingdom periods. Hassan proposed that Nynetjer was the owner of the tomb thanks to numerous seal impressions bearing his serekh found onsite.[note 10][127] The tomb was partially excavated in the 1970s to 1980s under the direction of Peter Munro,[128] then Günther Dreyer,[129] who both confirmed Hassan's proposition.[130] Thorough excavations continued during seven campaigns until the 2010s under the supervision of archaeologist Claudia Lacher-Raschdorff of the Deutsches Archäologisches Institut.[9]

Location

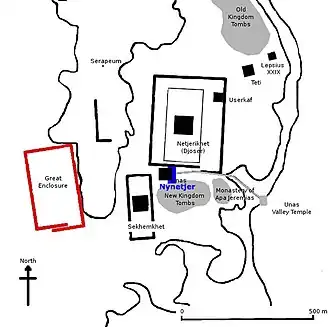

Nynetjer's tomb lies in North Saqqara. Now known as Gallery Tomb B, the ancient name of the tomb might originally have been "Nurse of Horus" or "Nurse of the God".[131] The tomb is located out of sight of Memphis,[132][133] next to a natural wadi—a dry river bed only active during flash floods—running west to east[133] which may have functioned as a causeway from the valley up to the local plateau. This location was not only convenient—the wadi serving as an accessway for bringing construction materials to the tomb—but also ensured that the tomb remained hidden from the Nile valley[134] and set within a desert backdrop symbolizing death which the king would finally overcome.[135]

Nynetjer's tomb, in the immediate vicinity of Hotepsekhemwy's and Raneb's,[136] now lies beneath the causeway of Unas (mid-24th century BC) built at the end of the fifth dynasty. By that time, the original entrance of the tomb had already been blocked by a ditch, which Djoser had dug around his own pyramid.[137]

To the south and east of the tomb, archaeological evidence suggests the presence of a wider necropolis of the second dynasty hosting the gallery tombs of several high ranking officials of the time.[138]

Superstructure

Archaeological excavations suggest the existence of above-ground structures originally associated with Nynetjer's tomb, none of which have survived.[133][136][139] What remains is not sufficient to determine the layout of the structures or if they were made of mud-brick or limestone.[133] For Munro the superstructure is unlikely to have been a giant mastaba covering the entire extent of the underground galleries, for this would have represented an immense quantity of materials of which there is scant traces today.[140] Nonetheless, Djoser may have levelled the structures and reused the construction materials for his own tomb complex,[141][142] which might also explain why some funerary provisions made for Hotepsekhemwy and Nynetjer were found in the galleries beneath Djoser's pyramid.[143] Consequently, the superstructures associated with Nynetjer's tomb must have been in ruins by the time of Unas[144] since this king had the whole area levelled for his pyramid. Alternatively, Unas rather than Djoser may be responsible for the destruction of Nynetjer's monuments.[145]

The superstructures likely incorporated an offering place with false door and niche stele, a mortuary temple and a serdab—a sealed chamber housing a Ka statue of the king.[146] The heights of these superstructures may have reached 8 to 10 metres (26 to 33 ft) and may have resembled a mastaba.[147] A separate enclosure wall built of stone was in all probability built as well,[148] such structures accompanying royal tombs since the first dynasty, albeit here likely on a much grander scale. The nearby Gisr el-Mudir (meaning "Great Enclosure") and L-shape enclosures may belong to Hotepsekhemwy and Nynetjer,[149][134] the later being a strong possibility for the "enormous" (Wilkinson) Gisr el-Mudir construction given his long reign.[150]

Substructures

Layout

The tomb comprises two vast subterranean ensembles hewn into the local rock. The main one, dug some 5 m (16 ft) to 6 m (20 ft) below ground level,[151] has 157 rooms of 2.1 m (6.9 ft) height over an area of 77 m × 50.5 m (253 ft × 166 ft).[133] The second ensemble is made of 34 rooms. The tomb was originally entered via a 25 m (82 ft)-long ramp blocked by two portcullises and leading to three galleries on a rough east-west axis. These extend into a maze-like system of doorways, vestibules and corridors built during two distinct construction phases.[133] Lacher-Raschdorff estimates that the tomb rooms and galleries could have been dug by a team of 90 people working over a duration of two years. Marks left by copper tools show that the workers were organised in several groups hewing the rock from different directions.[152]

The tomb shows great architectural similarities to Gallery Tomb A with its maze of subterranean rooms. Gallery Tomb A is located some 130 m (430 ft) to the west and which is thought to be either Raneb's or Hotepsekhemwy's burial site.[19] Yet Nynetjer's tomb marks an important development in monumental royal mortuary architecture. Its extended labyrinthine layout may have been meant to represent a city,[153] rather than a simple system of corridors and magazine chambers.[153] In this idea, a tomb room stood for a courtyard or for the entrance to a house, itself symbolised only by the massive bedrock. According to Lacher-Raschdorff, "the entire maze functioned as a model residence, with small streets, courtyards, dummy houses and dummy magazines".[153] Several groups of rooms can be discerned, three of which being model cult-places.[146][154] At the southern end of the tomb, a further group of chambers seems to be a model of the royal palace.[155][156] The idea of dummy buildings was continued after Nynetjer's reign as can be seen from Djoser's pyramid complex.[153]

Since its construction, the tomb has become highly unstable and the whole burial site is in danger of collapsing.[157][158]

Contents

Although in the main tomb south portcullises blocking the access few finds were dated to the second dynasty,[153] some chambers were found almost undisturbed,[159] holding some of Nynetjer's original burial goods. One such room included 560 jars of wine, some of which were still sealed by sealings bearing the king's name and covered by a thick net made of plant fibres. Another room produced fragments of a further 420 unfinished and unsealed wine jars which seem to have been deliberately broken in a ceremony at the time of burial.[133][160] Further vessels include a group decorated with red stripes that held jujube fruits[note 11] and up to ten jars of beer.[133] Excavations of the tomb also yielded about 150 stone tools comprising knives with and without handles, stone sickles, blades, scrapers, hatchets and many further fragments of stone tools. There were also numerous stone vessels and unworked pieces of stone left for producing further vessels in the afterlife.[133][160] Detailed examination of the stone tools revealed minor traces of use and residues of a reddish-brown liquid, but no identifiable wear from intensive use nor resharpening of the tools seems to have taken place; Lacher-Raschdorff therefore hypotheses that the tools were made for the burial of the king and used during a ceremony for slaughtering animals and preparing food.[162] In addition, some pieces of carved wood suggest the presence of a tent or canopy in the mortuary equipment of the king, similar to that found in the later tomb of queen Hetepheres I (fl. 2600 BC).[133]

Later usages

The northern part of Nynetjer's gallery tomb area was covered by the necropolis associated with the pyramid of Unas at the end of the fifth dynasty. At this time period, construction of the tombs of Nebkauhor and Iyenhor hit Nynetjer's galleries seemingly by chance.[163]

During the New Kingdom, an extensive private necropolis extended over the area. Several burial shafts broke into the subterranean galleries and some of rooms were reused as burial chambers.[164] A mummy mask, fragments of canopic jars, pottery sherds and coffins of the Ramesside era were uncovered there.[165]

Numerous mummy cases, mummies, statues of divinities were deposited in the tomb rooms during the Third Intermediate (c. 1077 – 664 BC) and the Late Periods (c. 664 – 332 BC).[50][166] Some of these finds could be dated precisely to the Twenty-seventh Dynasty of Egypt (525 BC – 404 BC).[166]

This area of the Saqqara necropolis remained in use sporadically until the early Christian period; in the sixth century, after it had fallen into disuse, the nearby monastery of Jeremiah was built.[133]

Notes

- ^ According to publications[1] as well as the purchase description of the Rijksmuseum van Oudheden in Leiden, the statue is made of alabaster, but doubts arose about this after purchase. In 2017, the statue was examined by geologist Hanco Zwaan of the Naturalis Biodiversity Center in Leiden who found it to be made of quartzite.[2]

- ^ Proposed dates for Nynetjer's reign: c. 2810 BC,[5] 2810–2760 BC,[6] 2790–2754 BC,[7] 2785–2742 BC,[8][9] 2767–2717 BC,[6] 2760–2715 BC,[10] c. 2700–2660 BC.[11]

- ^ Egyptologists sharing this opinion include Reader,[27] Wilkinson,[28][29][30] Kahl,[31] Vercoutter,[32] and Smith.[33]

- ^ In ancient Greek, Bίνωθρις.[45]

- ^ In ancient Greek, Βίοφις.[45]

- ^ With the exception of Ricci who proposed only 15 years of reign for Nynetjer in his 1917 appraisal of the Palermo stone.[47]

- ^ Helck points to the celebration of a Sed festival by Nynetjer. This was a rejuvenation feast that could only be first held after three decades of rule. Consequently, according to Helck, this supports a reign of at least 30 years.[48] Both Helck and Wilkinson see 35 years as the minimum possible duration for Nynetjer's reign given the space devoted to it on the royal annals.[48][19] In 1916, Georges Daressy had proposed 47 and a half years of reign of Nynetjer after studying the same annals.[46]

- ^ Dating these inscriptions made of black ink is difficult. Writing experts and archaeologists such as Ilona Regulski point out that the ink inscriptions may be of a somewhat later date than the stone and seal inscriptions. She dates the ink markings to the reigns of kings Khasekhemwy and Djoser and assumes that the artifacts originated from Abydos.[78] Others including Helck and Wilkinson believe the inscriptions do date to Nynetjer's rule.[79][80]

- ^ According to Jochem Kahl, Weneg is a name of Nynetjer's predecessor Raneb.[118]

- ^ The large mastaba of the high official Ruaben (or Ni-Ruab) who held his office during the reign of Nynetjer, now known as mastaba S2302, had been proposed to be Nynetjer's tomb until Hassan's proposal regarding Gallery Tomb B as the burial site of the king was confirmed. The earlier misinterpretations were caused by the large amount of clay seals with Nynetjer's serekh name that were found in Ruaben's mastaba.[68]

- ^ These fruits were utilized in ancient Egyptian medicine for their supposed anti-inflammatory properties, specifically in treating pain, swelling, and heat.[161]

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h Wilkinson 2005, p. 72.

- ^ Twee faraobeeltjes, Rijksmuseum van Oudheden 2023.

- ^ Simpson 1956, p. 46.

- ^ Emery 1961, p. 95.

- ^ Bierbrier 1999, pp. xviii & 263.

- ^ a b von Beckerath 1997, p. 187.

- ^ Chauvet 2001, p. 176.

- ^ von Beckerath 1999, p. 283.

- ^ a b Lacher-Raschdorff 2015, p. 47.

- ^ a b c d e Hornung & Lorton 1999, p. 11.

- ^ a b Hornung 2012, p. 490.

- ^ a b c Smith 1971, p. 31.

- ^ Kahl 2007, p. 16.

- ^ Bierbrier 1999, p. 175.

- ^ Clayton 1994, p. 26.

- ^ Wilkinson 2005, p. 173.

- ^ Grimal 1992, p. 54.

- ^ Sethe 1905, p. 23.

- ^ a b c d e Wilkinson 2005, p. 71.

- ^ Petrie & Griffith 1901, p. 5, obj. 6.

- ^ Kaplony 1964, fig. 1074.

- ^ Quibell 1923, Tomb S2171, pl. XV.3; Tomb S2302 pl. XVII.3 and p. 30; Tomb S2498 pp. 44–45.

- ^ Porter & Moss 1974, tomb S2171 p. 436, Tomb S2302 p. 437, Tomb S2498 p. 440.

- ^ Petrie 1907, p. 7, pl. VE.

- ^ Saad 1951, p. 17, pls XII.a & b, XIII.a.

- ^ a b c Žába 1974, pp. 30–31.

- ^ Reader 2017, p. 75.

- ^ Wilkinson 2005, p. 22.

- ^ Wilkinson 2010, p. 50.

- ^ a b Wilkinson 2014, p. 2.

- ^ Kahl 2007, p. 17.

- ^ Vercoutter 1992, p. 222.

- ^ a b Smith 1971, p. 30.

- ^ Fischer 1961, pp. 45–46.

- ^ Emery 1961, p. 35.

- ^ Petrie & Griffith 1901, p. 26.

- ^ Kahl 2007, p. 21.

- ^ Bárta 2017, p. 2.

- ^ Grimal 1992, p. 77.

- ^ Wilkinson 2000, pp. 24 & 119.

- ^ Helck 1987, pp. 116–117.

- ^ Fischer 1961, p. 46.

- ^ Daressy 1916, p. 205.

- ^ Mariette 1864, p. 20.

- ^ a b c d Waddell 1971, pp. 37–39.

- ^ a b Daressy 1916, p. 187.

- ^ a b Wilkinson 2000, p. 256.

- ^ a b Helck 1979, p. 128.

- ^ Wilkinson 2000, pp. 79–80.

- ^ a b c Baker 2008, pp. 281–283.

- ^ Gardiner 1959, p. 15, Table I.

- ^ a b c d Schott 1950, pp. 59–67.

- ^ Wilkinson 2005, p. 260.

- ^ a b Lacau & Lauer 1959, pl. 13, no. 63–66.

- ^ Wilkinson 2005, p. 252.

- ^ Lacau & Lauer 1959, pl. 16, no. 78.

- ^ a b Wilkinson 2005, p. 246.

- ^ Sethe 1905, p. 139.

- ^ Wilkinson 2005, pp. 253 & 260.

- ^ Wilkinson 2005, pp. 71–72.

- ^ a b Emery 1961, p. 93.

- ^ Reader 2014, p. 428.

- ^ Kahl 2007, pp. 44–46.

- ^ a b Kahl 2007, p. 57.

- ^ a b c d e Grimal 1992, p. 55.

- ^ Hornung 2012, p. 107.

- ^ Waddell 1971, p. 37.

- ^ a b Emery 1961, p. 94.

- ^ Emery 1964, pp. 104 & 175.

- ^ a b Wilkinson 2005, p. 105.

- ^ a b Kaplony 1963, fig. 749.

- ^ a b c Andrassy 2008, p. 16.

- ^ a b Haring 2010, p. 229.

- ^ a b Katary 2001, p. 352.

- ^ Kahl 2013, p. 311.

- ^ Andrassy 2008, p. 75.

- ^ Andrassy 2008, pp. 16 & 113.

- ^ Regulski 2004, pp. 949–970.

- ^ Helck 1979, p. 129.

- ^ a b Wilkinson 2005, p. 121.

- ^ a b Wilkinson 2005, p. 117.

- ^ Shaw & Nicholson 1995, p. 15.

- ^ a b Fritschy 2018, p. 169.

- ^ Wilkinson 2005, p. 108.

- ^ Lacau & Lauer 1959, pl. 14, no. 70.

- ^ Kaplony 1963, figs 746, 748.

- ^ Petrie & Griffith 1901, pp. 26–27, see also pl. VIII.13.

- ^ Andrassy 2008, p. 13.

- ^ Wilkinson 2005, pp. 99–100.

- ^ Wilkinson 2005, p. 103.

- ^ Hoffman 1990, p. 325.

- ^ Wilkinson 2005, p. 94.

- ^ Roth 1991, p. 216.

- ^ Kahl 1994, p. 880.

- ^ Faltings & Köhler 1996, p. 100, n. 52.

- ^ Lacau & Lauer 1965, pp. 3–8, pls. 2–9 [no. 2–8].

- ^ Emery 1961, pp. 93–94.

- ^ Wilkinson 2010, p. 51.

- ^ Regulski 2004, p. 962.

- ^ Wilkinson 2000, p. 73.

- ^ a b Baines & Málek 2000, p. 32.

- ^ Wilkinson 2005, pp. 69 & 77–79.

- ^ Wilkinson 2005, p. 69.

- ^ Wilkinson 2005, pp. 69–70.

- ^ Wilkinson 2005, p. 70.

- ^ Baines & Málek 2000, p. 36.

- ^ Shaw 2000, p. 482.

- ^ a b c d e Schlögl 2019, p. 27.

- ^ a b Tiradritti & Donadoni Roveri 1998, pp. 80–85.

- ^ a b Bell 1970, pp. 571–572.

- ^ Wilkinson 2005, p. 191.

- ^ Wilkinson 2005, p. 180.

- ^ Helck 1979, p. 132.

- ^ Wilkinson 2005, p. 75.

- ^ Hoffman 1990, p. 312.

- ^ Seidlmayer 2001, pp. 87–89.

- ^ Wilkinson 2010, pp. 50–51.

- ^ Hornung 2012, pp. 21 & 102–103.

- ^ Smith 1971, p. 25.

- ^ Helck 1979, pp. 120–132.

- ^ Wilkinson 1999, p. 89.

- ^ Wilkinson 2005, pp. 73 & 75.

- ^ Hornung 2012, p. 104.

- ^ Schlögl 2019, p. 28.

- ^ Grimal 1992, pp. 55–57.

- ^ Tristant 2018, p. 140.

- ^ Hassan 1938, pp. 503–521.

- ^ Munro 1983, pp. 277–295.

- ^ Dreyer 2007, pp. 130–138.

- ^ Wilkinson 2014, p. 4.

- ^ Stadelmann 1981, p. 163.

- ^ Sullivan 2016, p. 83.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Lacher-Raschdorff 2014, p. 251.

- ^ a b Reader 2004, p. 66.

- ^ Sullivan 2016, p. 85.

- ^ a b Málek 2000, p. 79.

- ^ Wilkinson 2010, p. 67.

- ^ Reader 2017, pp. 76–77.

- ^ Baines & Málek 2000, p. 142.

- ^ Munro 1993, p. 50.

- ^ Munro 1993, pp. 48–49.

- ^ Roth 1993, p. 48, n. 49.

- ^ Wilkinson 2005, p. 217.

- ^ Wilkinson 2005, p. 209.

- ^ Sullivan 2016, p. 78.

- ^ a b Wegner 2018, p. 622.

- ^ Sullivan 2016, p. 80, see also fig. 2.

- ^ Wengrow 2009, p. 250.

- ^ Dodson 2010, p. 807.

- ^ Wilkinson 2005, p. 211.

- ^ Reader 2017, pp. 75 & 84.

- ^ Lacher-Raschdorff 2015, p. 48.

- ^ a b c d e Lacher-Raschdorff 2011, p. 542.

- ^ Lacher-Raschdorff 2011, p. 540.

- ^ Reader 2017, p. 76.

- ^ Lacher-Raschdorff 2014, pp. 59 & 251.

- ^ Emery 1964, pp. 104–105.

- ^ Van Wetering 2004, pp. 1065–1066.

- ^ Tristant 2018, p. 141.

- ^ a b Lacher-Raschdorff 2015, pp. 48–49.

- ^ Kadioglu et al. 2016, pp. 361–369.

- ^ Lacher-Raschdorff 2015, p. 49.

- ^ Lacher-Raschdorff 2014, p. 543.

- ^ Lacher-Raschdorff 2011, p. 545.

- ^ Lacher-Raschdorff 2011, pp. 545–546.

- ^ a b Lacher-Raschdorff 2011, p. 548.

Bibliography

- Andrassy, Petra (2008). Untersuchungen zum Ägyptischen Staat des Alten Reiches und seinen Institutionen. Internet-Beiträge zur Ägyptologie und Sudanarchäologie (in German). Vol. XI. Berlin/London: Golden House Publications. ISBN 978-1-906137-08-3. Archived from the original on 2018-03-26.

- Baines, John; Málek, Jaromír (2000). Cultural Atlas of Ancient Egypt. New York: Facts on File. ISBN 978-0-8160-4036-0.

- Baker, Darrell (2008). The Encyclopedia of the Pharaohs: Volume I – Predynastic to the Twentieth Dynasty 3300–1069 BC. London: Stacey International. ISBN 978-1-905299-37-9.

- Bárta, Miroslav (2017). "Radjedef to the Eighth Dynasty". UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology.

- Bell, Barbara (1970). "Oldest Records of the Nile Floods". Geographical Journal. 136 (4): 569–573. Bibcode:1970GeogJ.136..569B. doi:10.2307/1796184. JSTOR 1796184.

- Bierbrier, Morris (1999). Historical Dictionary of Ancient Egypt. Lanham, Maryland: The Scarecrow Press, Inc. ISBN 0-8108-3614-9.

- Chauvet, Violaine (2001). "Saqqara". In Redford, Donald B. (ed.). The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt. Vol. 3. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 176–179. ISBN 978-0-19-510234-5.

- Clayton, Peter A. (1994). Chronicle of the Pharaohs. London: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-05074-3.

- Daressy, Georges (1916). "La Pierre de Palerme et la Chronologie de l'Ancien Empire". Bulletin de l'Institut Français d'Archéologie Orientale (in French). 12 (9): 161–214. doi:10.3406/bifao.1916.1736.

- Dodson, Aidan (2010). "Mortuary Architecture and Decorative Systems". In Lloyd, Alan B. (ed.). A Companion to Ancient Egypt. Blackwell Companions to the Ancient World. Vol. I. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 804–825. ISBN 978-1-4051-5598-4.

- Dreyer, Günter (2007). "Ein unterirdisches Labyrinth: Das Grab des Königs Ninetjer in Sakkara". In Dreyer, Günter; Polz, Daniel (eds.). Begegnung mit der Vergangenheit: 100 Jahre in Ägypten: Deutsches Archäologisches Institut Kairo 1907-2007 (in German). Mainz am Rhein: Philipp von Zabern. pp. 130–138. ISBN 978-3-80-533793-9.

- Emery, Walter B. (1961). Archaic Egypt. Pelican Book. Vol. A462 (1st ed.). Harmondsworth: Penguin Books. OCLC 636876268.

- Emery, Walter B. (1964). Ägypten—Geschichte und Kultur der Frühzeit (in German). Wiesbaden: Fourier-Verlag. ISBN 3-921695-39-2.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - Faltings, Dina; Köhler, Christiana E. (1996). "Vorbericht über die Ausgrabungen des DAI in Tell el-Fara'in/Buto 1993 bis 1995". Mitteilungen des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts Kairo. 52: 87–114.

- Fischer, Henry George (1961). "An Egyptian Royal Stela of the Second Dynasty". Artibus Asiae. 24 (1): 45–56. doi:10.2307/3249184. JSTOR 3249184.

- Fritschy, Wantje (2018). "The pr-ḥḏ and the Early Dynastic State". The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology. 104 (2): 161–176. doi:10.1177/0307513319856853. JSTOR 26843204.

- Gardiner, Alan (1959). The Royal Canon of Turin. Oxford: Griffith Institute. OCLC 21484338.

- Grimal, Nicolas (1992). A History of Ancient Egypt. Translated by Ian Shaw. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 978-0-631-19396-8.

- Haring, Ben (2010). "Administration and Law: Pharaonic". In Lloyd, Alan B. (ed.). A Companion to Ancient Egypt. Blackwell Companions to the Ancient World. Vol. I. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 218–236. ISBN 978-1-4051-5598-4.

- Hassan, Selim (1938). "Excavations at Saqqara, 1937–1938". Annales du Service de Antiquités de l'Égypte (in French). 38. Cairo: Imprimerie de l'Institut Français d'Archéologie Orientale. OCLC 230793245.

- Helck, Wolfgang (1979). "Die Datierung der Gefäßaufschriften der Djoserpyramide". Zeitschrift für Ägyptische Sprache und Altertumskunde (in German). 106 (1). Berlin: De Gruyter: 120–132. doi:10.1524/zaes.1979.106.1.120.

- Helck, Wolfgang (1987). Untersuchungen zur Thinitenzeit. Ägyptologische Abhandlungen (in German). Vol. 45. Wiesbaden: Otto Harrassowitz. ISBN 978-3-44-702677-2.

- Hoffman, Michael A. (1990). Egypt Before the Pharaohs: The Prehistoric Foundations of Egyptian Civilization. New York: Dorset. ISBN 978-0-88-029457-7.

- Hornung, Erik; Lorton, David (1999). History of Ancient Egypt: An Introduction. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press. ISBN 0-8014-8475-8.

- Hornung, Erik; Krauss, Rolf; Warburton, David, eds. (2012). Ancient Egyptian Chronology. Handbook of Oriental Studies. Leiden, Boston: Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-11385-5. ISSN 0169-9423.

- Kadioglu, Onat; Jacob, Stefan; Bohnert, Stefan; Naß, Janine; Saeed, Mohamed E M; Khalid, Hassan; Merfort, Irmgard; Thines, Eckhard; Pommerening, Tanja; Efferth, Thomas (April 2016). "Evaluating Ancient Egyptian Prescriptions Today: Anti-Inflammatory Activity of Ziziphus spina-christi". Phytomedicine. 23 (4): 361–369. doi:10.1016/j.phymed.2016.01.004. PMID 26969383.

- Kahl, Jochem (1994). Das System der Ägyptischen Hieroglyphenschrift in der 0.–3. Dynastie. Göttinger Orientforschungen. IV. Reihe Ägypten (in German). Vol. 29. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz. ISBN 978-3-447-03499-9.

- Kahl, Jochem (2007). "Ra is my Lord": Searching for the Rise of the Sun God at the Dawn of Egyptian History. Menes. Vol. 1. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz. ISBN 978-3-44-705540-6.

- Kahl, Jochem (2013). "Review, "Lo Stato egiziano nelle fonti scritte del periodo tinita" by Simone Lanna". Journal of Near Eastern Studies. 72 (2). Chicago: The University of Chicago Press: 310–312. doi:10.1086/671441. JSTOR 10.1086/671441.

- Katary, Sally L. D. (2001). "Saqqara". In Redford, Donald B. (ed.). The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt. Vol. 3. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 351–356. ISBN 978-0-19-510234-5.

- Kaplony, Peter (1963). Die Inschriften der Ägyptischen Frühzeit, vol III. Ägyptologische Abhandlungen (in German). Vol. 8. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz. OCLC 1405045400.

- Kaplony, Peter (1964). Die Inschriften der Ägyptischen Frühzeit, Supplement. Ägyptologische Abhandlungen (in German). Vol. 9. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz. OCLC 560543509.

- Lacau, Pierre; Lauer, Jean-Philippe (1959). La Pyramide à Degrés IV. Inscriptions Gravées sur les Vases (in French). Cairo: Institut Français d'Archéologie Orientale. OCLC 490561264.

- Lacau, Pierre; Lauer, Jean-Philippe (1965). La Pyramide à Degrés V. Inscriptions à l'Encre sur les Vases (in French). Cairo: Institut Français d'Archéologie Orientale. OCLC 490561320.

- Lacher-Raschdorff, Claudia (2011). "The tomb of king Ninetjer and its reuse in later

periods". In Bárta, Miroslav; Coppens, Filip; Krejčí, Jaromír (eds.). Abusir and Saqqara in the year 2010/1. Prague: Czech Institute of Egyptology, Faculty of Arts, Charles University. pp. 537–550. ISBN 978-8-07-308384-7. {{cite book}}: line feed character in |chapter= at position 49 (help)

- Lacher-Raschdorff, Claudia (2014). Das Grab des Königs Ninetjer in Saqqara: Architektonische Entwicklung Frühzeitlicher Grabanlagen in Ägypten. Archäologische Veröffentlichungen / Deutsches archäologisches Institut, Abteilung Kairo (in German). Vol. 125. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz. ISBN 978-3-44-706999-1.

- Lacher-Raschdorff, Claudia (2015). "Saqqara, Ägypten: Das Grab des Königs Ninetjer". Elektronische Publikationen des Deutschen Archäologischen Insituts, e-Forschungsberichte (in German) (1). Berlin: Deutsches Archäologisches Institut: 47–49.

- Málek, Jaromir (2000). "The Old Kingdom (c. 2686 – 2160 BC)". In Shaw, Ian (ed.). The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 83–107. ISBN 978-0-19-815034-3.

- Mariette, Auguste (1864). "La Table de Saqqarah". La Revue Archéologique (in French). 10. Paris.

- Munro, Peter (1983). "Einige Bemerkungen zum Unas-Friedhof in Saqqara: 3. Vorbericht über die Arbeiten der Gruppe Hannover im Herbst 1978 und im Frühjahr 1980". Studien zur Altägyptischen Kultur (in German). 10: 277–295. JSTOR 44325742.

- Munro, Peter (1993). "Report on the Work of the Joint Archaeological Mission Free University Berlin/University of Hannover During Their 12th Campaign (15th March until 14th May, 1992) at Saqqara". Discussions in Egyptology. 26: 47–58.

- Petrie, W. M. Flinders; Griffith, Francis Llewellyn (1901). The Royal Tombs of the Earliest Dynasties (PDF). London: Egypt Exploration Fund. OCLC 863347205.

- Petrie, W. M. Flinders (1907). Gizeh and Rifeh. British School of Archaeology in Egypt and Egyptian Research Account. London: B. Quaritch. OCLC 457589594.

- Porter, Bertha; Moss, Rosalind L. B. (1974). Topographical Bibliography of Ancient Egyptian Hieroglyphic Texts, Reliefs, and Paintings, III. Memphis (2nd ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press at the Clarendon Press. OCLC 1055086223.

- Quibell, James Edward (1923). Excavations at Saqqara (1912–1914). Archaic Mastabas. Vol. 6. Cairo: Institut français d'archéologie orientale. OCLC 1000299831.

- Reader, Colin (2004). "On Pyramid Causeways". The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology. 90: 63–71. doi:10.1177/030751330409000104. JSTOR 3822244.

- Reader, Colin (2014). "The Netjerikhet Stela and the Early Dynastic Cult of Ra". The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology. 100: 421–435. doi:10.1177/030751331410000122. JSTOR 24644981.

- Reader, Colin (2017). "An Early Dynastic Ritual Landscape at North Saqqara: An Inheritance from Abydos?". The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology. 103 (1): 71–87. doi:10.1177/0307513317722459.

- Regulski, Ilona (2004). "2nd Dynasty Ink Inscriptions from Saqqara paralleled in the Royal Museums of Art and History, Brussels". Egypt at its Origins. Studies in Memory of Barbara Adams. Proceedings of the International Conference "Origin of the State. Predynastic and Early Dynastic Egypt" (OLA). Vol. 138. Leuven: Peeters Leuven. pp. 949–970. ISBN 978-9-04-291469-8.

- Roth, Ann Macy (1991). Egyptian Phyles in the Old Kingdom. The Evolution of a System of Social Organization. Studies in Ancient Oriental Civilization. Vol. 48. Chicago: The Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago. ISBN 978-0-91-898668-9.

- Roth, Ann Macy (1993). "Social Change in the Fourth Dynasty: The Spatial Organization of Pyramids, Tombs, and Cemeteries". Journal of the American Research Center in Egypt. 30: 33–55. doi:10.2307/40000226. JSTOR 40000226.

- Saad, Zaki Youssef (1951). Royal excavations at Helwan (1945-1947). Supplément aux Annales du Service des Antiquités de l’Egypte. Vol. Cahier 14. Cairo: Institut Français d'Archéologie Orientale. OCLC 470808020.

- Schlögl, Hermann A. (2019). Das alte Ägypten. C. H. Beck Paperback (in German). Vol. 2305 (5th, revised ed.). München: C. H. Beck. ISBN 978-3-40-673174-7.

- Schott, Siegfried (1950). Altägyptische Festdaten (in German). Wiesbaden: Verlag der Akademie der Wissenschaften und der Literatur in Mainz in Kommission bei Franz Steiner Verlag GMBH. OCLC 875761868.

- Seidlmayer, Stephan Johannes (2001). Historische und moderne Nilstände: Historische und moderne Nilstände: Untersuchungen zu den Pegelablesungen des Nils von der Frühzeit bis in die Gegenwart (in German). Berlin: Achet. ISBN 978-3-9803730-8-1.

- Sethe, Kurt (1905). Beiträge zur ältesten Geschichte Ägyptens. Untersuchungen zur Geschichte und Altertumskunde Ägyptens. Vol. 3. Leipzig: Hinrichs. doi:10.11588/diglit.13808. OCLC 1068651310.

- Shaw, Ian; Nicholson, Paul T. (1995). The British Museum Dictionary of Ancient Egypt. London: British Museum Press. ISBN 978-0-71-410982-4.

- Shaw, Ian, ed. (2000). "Chronology". The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 481–489. ISBN 978-0-19-815034-3.

- Simpson, William Kelly (1956). "A Statuette of King Nyneter". The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology. 42: 45–49. doi:10.2307/3855121. JSTOR 3855121.

- Smith, William Stevenson (1971). "The Old Kingdom of Egypt and the Beginning of the First Intermediate Period". In Edwards, I. E. S.; Gadd, C. J.; Hammond, N. G. L. (eds.). The Cambridge Ancient History, Volume 1, Part 2. Early History of the Middle East (3rd ed.). London, New York: Cambridge University Press. pp. 22–35. ISBN 9780521077910. OCLC 33234410.

- Stadelmann, Rainer (1981). "Die [khentjou-she], der Königsbezirk [she n per-âa] und die Namen der Grabanlagen der Frühzeit". Bulletin de l'Institut Français d'Archéologie Orientale (in German). 81 (1). Cairo: Institut Français d’Archéologie Orientale: 153–164.

- Sullivan, Elaine (2016). "Potential Pasts: Taking a Humanistic Approach to Computer Visualization of Ancient Landscapes". Bulletin of the Institute of Classical Studies. 59 (2): 71–88. doi:10.1111/j.2041-5370.2016.12039.x. JSTOR 44254154.

- Tiradritti, Francesco; Donadoni Roveri, Anna Maria (1998). Kemet: Alle Sorgenti Del Tempo (in Italian). Milano: Electa. ISBN 978-8-84-356042-4.

- Tristant, Yann (2018). "Das Grab des Königs Ninetjer in Saqqara. Architektonische Entwicklung frühzeitlicher Grabanlagen in ÄgyptenClaudia M. Lacher-Raschdorff Archäologische Veröffentlichungen 125, Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden, 2014 [compte-rendu]". Archéo-Nil. Revue de la Société pour l'Étude des Cultures Prépharaoniques de la Vallée du Nil (in French). 28: 140–142.

- "Twee Faraobeeltjes". Rijksmuseum van Oudheden (in Dutch). Leiden. 2013-10-17. Archived from the original on 2023-01-17. Retrieved 2024-04-21.

- Van Wetering, Joris (2004). "The royal cemetery of the early Dynastic period at Saqqara and the Second Dynasty royal tombs". In Hendrickx, Stan; Friedman, Renée; Ciałowicz, Krzysztof M.; Chłodnicki, Marek (eds.). Egypt at its origins: Studies in memory of Barbara Adams. Proceedings of the International Conference "Origin of the State. Predynastic and Early Dynastic Egypt", Kraków, 28th August–1st September 2002. Vol. 138. Leuven: Orientalia Lovaniensia Analecta. pp. 1055–1080. ISBN 978-9-04-291469-8.

- Vercoutter, Jean (1992). L'Égypte et la Vallée du Nil. Tome 1: Des origines à la fin de l'Ancien Empire (12000–2000 avant J.C.) (in French). Paris: Presses universitaires de France. ISBN 978-2-13-059136-8.

- von Beckerath, Jürgen (1997). Chronologie des pharaonischen Ägypten: Die Zeitbestimmung der ägyptischen Geschichte von der Vorzeit bis 332 v. Chr. Münchner Ägyptologische Studien (in German). Vol. 46. Mainz am Rhein: Philipp von Zabern. ISBN 978-3-8053-2310-9.

- von Beckerath, Jürgen (1999). Handbuch der ägyptischen Königsnamen. Münchner Ägyptologische Studien (in German). Mainz: Philip von Zabern. ISBN 978-3-8053-2591-2.

- Waddell, William Gillan (1971). Manetho. Loeb Classical Library. Vol. 350. Cambridge, Massachusetts; London: Harvard University Press; W. Heinemann. OCLC 6246102.

- Wegner, M. A. Pouls (2018). "Das Grab des Königs Ninetjer in Saqqara: Architektonische Entwicklung frühzeitlicher Grabanlagen in Ägypten by Claudia M. Lacher-Raschdorff. Review by: M. A. Pouls Wegner". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 138 (3): 621–623.

- Wengrow, David (2009). The Archaeology of Early Egypt: Social Transformations in North-East Africa; 10,000 to 2,650 BC. Cambridge World Archaeology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-54374-3.

- Wilkinson, Toby A. H. (1999). Early Dynastic Egypt: Strategy, Society and Security. London: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-18633-1.

- Wilkinson, Toby A. H. (2000). Royal Annals of Ancient Egypt. The Palermo Stone and its Associated Fragments. London/New York: Kegan&Paul International. ISBN 978-0-7103-0667-8.

- Wilkinson, Toby A. H. (2005). Early Dynastic Egypt. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-203-02438-6.

- Wilkinson, Toby A. H. (2010). "The Early Dynastic Period". In Lloyd, Alan B. (ed.). A Companion to Ancient Egypt. Blackwell Companions to the Ancient World. Vol. I. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 48–62. ISBN 978-1-4051-5598-4.

- Wilkinson, Toby A. H. (2014). Grajetzki, Wolfram; Wendrich, Willeke (eds.). "Dynasties 2 and 3". UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology. 1 (1). Los Angeles: University of California Los Angeles.

- Žába, Zbyněk (1974). The Rock Inscriptions of Lower Nubia (Czechoslovak Concession). Publications (Československý Egyptologický Ústav). Vol. 1. Prague: Charles University. OCLC 6047001.