Navigation and seamanship of James Cook

Captain James Cook's feats of seamanship and his navigation skills enabled him to lead three expeditions – which travelled tens of thousands of miles across mostly uncharted oceans – that successfully gathered vast amounts of scientific and geographic knowledge, without the loss of a single ship.[1] His three voyages vastly expanded Europeans' knowledge of the Pacific Ocean, and revealed the existence of several new lands and cultures, including the Hawaiian archipelago.[2]

Beaglehole notes that, despite Cook's wide-ranging and significant achievements, he ultimately did not succeed in attaining important goals the Admiralty had hoped for: "If we contemplate these voyages of Cook against the background of geographical thought, or as exercises in the strategy of empire, we may consider their results as primarily negative. There was no [Southern] continent. There was no north-west passage. There was to be no grand struggle for the domination of the lakes and forests and fertile plains of the Terra Australis, no deployment there of armies or the corruptions of a massive trade or the disembowelment of gold mines, or the campaigning of humane men for the first decencies."[3]

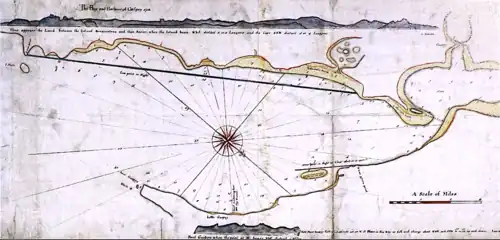

Hydrography and charting

Cook was an expert surveyor, cartographer, and hydrographer; and was well-versed in the use of instruments such as the theodolite, plane table, and sextant.[5] The charts of Newfoundland compiled by Cook were more accurate than new charts produced by the Royal Navy one hundred years later.[6] The charting skills he displayed in Newfoundland were a significant factor in his selection to lead the first Pacific voyage.[7]

The Endeavour expedition was the first exploration voyage to use Greenwich as the prime meridian, simply because the Nautical Almanac tables for the lunar distance method had been compiled under the supervision of an astronomer based in Greenwich.[8]

During the Seven Years' War, Cook served in North America as master aboard the fourth-rate Navy vessel HMS Pembroke.[9] With others in Pembroke's crew, he took part in the major amphibious assault that captured the Fortress of Louisbourg from the French in 1758.[10]

The day after the fall of Louisbourg, Cook met an army officer, Samuel Holland, who was using a plane table to survey the area.[11] The two men had an immediate connection through their interest in surveying, and Holland taught Cook the methods he was using.[12] They collaborated on developing preliminary charts of the entrance to the Saint Lawrence River, with Cook most likely the author of the sailing directions for the river written in 1758.[13] Cook's first map to be engraved and printed was of Gaspé Bay, drawn in 1758 and published in 1759.[4] The integration of Holland's land-surveying techniques with Cook's hydrographic expertise enabled Cook, from that point forward, to produce nautical charts of coastal regions that significantly exceeded the accuracy of most contemporary charts.[14]

As Major-General James Wolfe's advance on Quebec progressed in 1759, Cook and other ship's masters took soundings, marked shoals, and updated charts – particularly around Quebec. This information enabled Wolfe to mount a stealth attack at night, transporting troops across the river, leading to victory in the Battle of the Plains of Abraham.[15]

Chronometers and longitude

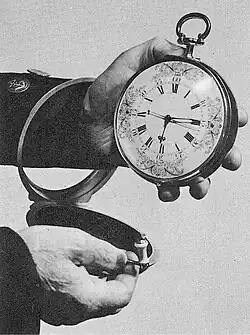

Cook's naval career coincided with the advent of practical methods of determining longitude. On his first voyage, Cook had available the 1768 and 1769 editions of the recently developed Nautical Almanac. The first edition of Maskelyne's Nautical Almanac covered 1767. It is possible that the tables that Cook used for 1769 were advance copies or manuscript versions, instead of the final printed edition for that year. Cook commented on the need for these tables to be prepared a long time in advance, as navigators on long voyages were those most in need of them.[17] The Almanac significantly streamlined the time taken to calculate longitude from lunar distance observations.[17] The lunar distance calculations carried out on Samuel Wallis's voyage (on which Tahiti was discovered) took about four hours. With the tables in the Almanac, this was reduced to one hour. The tables of the Almanac were primarily used by Endeavour's astronomer Charles Green. When the data in the Almanac ran out at the end of 1769, Cook had to revert to the more lengthy calculations.[17]

On his second and third voyages, Cook carried Larcum Kendall's K1 chronometer – a copy of John Harrison's H4 – to test if it could accurately keep time for extended periods while withstanding the violent motions of a ship and the temperature changes of different climates. It performed well and thus made a key contribution to solving the longitude problem that had plagued mariners for centuries.[18] Cook praised the timepiece profusely.[19]

On his second voyage, Cook also tested chronometers made by another manufacturer: James Arnold. Three instruments by Arnold were carried, but these did not perform well. Cook's report, and the consequent cessation of the Board of Longitude's funding to Arnold, caused him to make significant improvements to his design. The result, completed in 1779, was a pocket chronometer of particularly good performance. Arnold's advantage as a manufacturer was that he was able to produce chronometers in quantity, unlike Harrison's more limited output. He was the first watchmaker to make effective chronometers in volume.[20]

Cook's testing of chronometers relied on him having the lunar distance method to check their timekeeping. On all three of his voyages, he therefore needed Nautical Almanacs that had been prepared sufficiently ahead to cover the duration of the voyage, but in each case, the voyage lasted longer than the tables in the almanacs he had brought with him, and he had to revert to using lengthier calculations.[21][18]

Health and scurvy

Cook was among the pioneers in the early efforts to prevent scurvy, implementing various strategies including the provision of wort to the crew and the regular resupply of fresh food during voyages.[22] During his first circumnavigation of the globe, he did not lose a single crew member to the disease – an uncommon outcome at the time.[23] In addition to a healthier diet, Cook also promoted general hygiene by having the crew wash themselves frequently and air-out their bedding, clothes, and quarters.[24] He presented a paper on scurvy prevention to the Royal Society, and he was awarded their prestigious Copley Medal for contributions to medical and naval science.[25]

Cook's paper on scurvy incorrectly concluded that sweet wort and malt were important to preventing scurvy. In fact, scurvy is prevented by eating foods that contain vitamin C, such as citrus fruits.[26] Prior to Cook's first voyage, some British physicians, such as James Lind and Nathaniel Hulme, had concluded that citrus fruits were a solution, but Cook did not adopt that recommendation.[26] The wort and malt identified by Cook did not contain vitamin C. Cook's success with scurvy was due to frequent replenishment of fresh food, and to various plant materials sometimes brewed into the beer prepared on ship. Cook's erroneous conclusion delayed the adoption of successful antiscorbutic measures by the Royal Navy.[26]

References

Citations

- ^

- Beaglehole 1974, pp. 169, 219, 235, 248, 417–418, 608, 699.

- Salmond 2004, p. 292.

- Williams 2008, p. 1.

- ^

- Beaglehole 1974, p. 699.

- Thomas 2003, p. xx.

- Deacon & Deacon 1969.

- ^ Beaglehole & Cook 1968, pp. cxx–cxxi.

- ^ a b

- Beaglehole 1974, p. 34.

- Hayes 2015, pp. 106–107.

- ^

- Skelton 1954, pp. 106, 119.

- Beaglehole 1974, pp. 33, 50, 60, 67, 69–70, 80, 99, 136.

- Hough 1994, pp. 24, 28, 30, 33, 134.

- ^ Hough 1994, p. 33.

- ^

- Skelton 1954, p. 92.

- Hough 1994, p. 38.

- ^ Skelton 1954, p. 118.

- ^ Hough 1994, pp. 14–23.

- ^

- Beaglehole 1974, pp. 32–33.

- Hough 1994, pp. 16–19.

- ^ Hough 1994, p. 18.

- ^

- Skelton 1954, pp. 97–99.

- Hayes 2015, pp. 106–107.

- ^ Beaglehole 1974, pp. 37–39.

- ^

- Beaglehole 1974, pp. 33, 40–41.

- McLynn 2011, p. 34.

- ^

- Beaglehole 1974, pp. 43–49.

- Skelton 1954, p. 93.

- Hough 1994, pp. 18–19.

- McLynn 2011, pp. 37–38.

- Hayes 2015, pp. 106–107.

- ^

- Betts 2018, p. 186.

- Clark 2017.

- ^ a b c

- Cock 1999.

- Beaglehole 1974, p. 116.

- Skelton 1954, pp. 111, 118.

- Beaglehole & Cook 1968, pp. clxvii, 392.

- ^ a b Hough 1994, pp. 192–193, 197, 236.

- ^ Hough 1994, pp. 197, 236.

- ^ Sobel 2011, p. 181.

- ^ Howse 1989, pp. 86–87.

- ^

- Stubbs 2003.

- Cook 1776.

- Beaglehole 1974, pp. 703–704.

- Salmond 2004, pp. 62–63, 192, 235, 244, 386–387.

- ^

- Thomas 2003, p. 164.

- Beaglehole 1974, pp. 703–704.

- Hough 1994, pp. 266–267.

- ^

- Salmond 2004, pp. 161, 176, 185.

- Hough 1994, pp. 200, 207, 219.

- ^

- Hough 1994, p. 284.

- Cook 1776.

- ^ a b c Stubbs 2003.

Sources

- Beaglehole, John (ed.); Cook, James (1968) [1955]. The Journals of Captain James Cook on His Voyages of Discovery. Vol. I: The Voyage of the Endeavour 1768–1771. Cambridge University Press. OCLC 223185477. Retrieved 23 May 2025 – via Hakluyt Society.

- Beaglehole, John (1974). The Life of Captain James Cook. Stanford University Press. ISBN 0804708487. Retrieved 23 May 2025. Sometimes titled The Journals of Captain James Cook on His Voyages of Discovery Vol. IV: The Life of Captain James Cook.

- Betts, Jonathan (2018). Marine Chronometers at Greenwich: A Catalogue of Marine Chronometers at the National Maritime Museum, Greenwich. OUP Oxford. ISBN 9780191511172.

- Clark, Gregory (2017). "The Annual RPI and Average Earnings for Britain, 1209 to Present (New Series)". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved 7 May 2024. All inflation computations used in this article are based on this resource.

- Cock, Randolph (1 January 1999). "Precursors of Cook: The Voyages of the Dolphin, 1764–8". The Mariner's Mirror. 85 (1): 30–52. doi:10.1080/00253359.1999.10656726. ISSN 0025-3359. Retrieved 3 August 2025.

- Cook, James (31 December 1776). "The Method Taken for Preserving the Health of the Crew of His Majesty's Ship the Resolution During Her Late Voyage Round the World". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society. 66. Royal Society: 402–406. doi:10.1098/rstl.1776.0023. ISSN 2053-9223. Retrieved 11 June 2025.

- Deacon, G. E. R.; Deacon, Margaret (1969). "Captain Cook as a Navigator". Notes and Records of the Royal Society of London. 24 (1): 33–42. doi:10.1098/rsnr.1969.0005. ISSN 0035-9149.

- Hayes, Derek (2015) [2002]. Historical Atlas of Canada. Douglas & McIntyre. ISBN 9781771620796. Retrieved 7 August 2025.

- Hough, Richard (1994). Captain James Cook. W. W. Norton. ISBN 0393036804. Retrieved 30 May 2025. First American Edition.

- Howse, Derek (1989). Nevil Maskelyne, the seaman's astronomer. Cambridge [England] ; New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 052136261X. Retrieved 8 August 2025.

- McLynn, Frank (2011). Captain Cook: Master of the Seas. Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300114218. Retrieved 29 May 2025.

- Salmond, Anne (2004) [2003]. The Trial of the Cannibal Dog: The Remarkable Story of Captain Cook's Encounters in the South Seas. Penguin Books. ISBN 0141021330.

- Skelton, R. A. (Peter) (1954). "Captain James Cook as a Hydrographer (The Society's Annual Lecture)". The Mariner's Mirror. 40 (2). Routledge: 91–119. doi:10.1080/00253359.1954.10658197. ISSN 0025-3359. Retrieved 20 July 2025. Paper was originally sponsored and published by the Hakluyt Society.

- Sobel, Dava (2011) [1995]. Longitude: the True Story of a Lone Genius Who Solved the Greatest Scientific Problem of His Time. Harper Perennial. ISBN 9780007214228.

- Stubbs, Brett (2003). "Captain Cook's Beer: the Antiscorbutic Use of Malt and Beer in Late 18th Century Sea Voyages". Asia Pacific Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 12 (2): 129–137. ISSN 0964-7058. PMID 12810402.

- Thomas, Nicholas (2003). Cook: The Extraordinary Voyages of Captain James Cook. Walker & Co. ISBN 0802777112. Retrieved 3 June 2025.

- Williams, Glyndwr (2008). The Death of Captain Cook: A Hero Made and Unmade. Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674031944. Retrieved 3 June 2025.

External links

- Works by or about Navigation and seamanship of James Cook at the Internet Archive – Digitised books and documents

- Works by Navigation and seamanship of James Cook at Project Gutenberg – Digitised books and documents

- Works by Navigation and seamanship of James Cook at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)