Nathaniel Turner (missionary)

Rev. Nathaniel Turner | |

|---|---|

.jpg) Nathaniel Turner, Missionary | |

| Born | March 1793 |

| Died | 16 December 1864 (aged 70) Brisbane, Queensland, Australia |

| Occupation | Wesleyan Methodist Missionary |

| Spouse | Anne Turner née Sargent |

| Children | fourteen children |

| Parents |

|

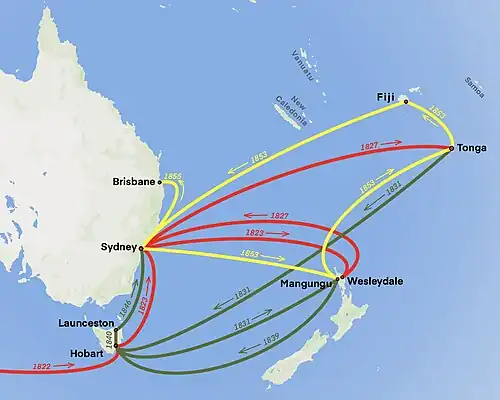

Nathaniel Turner (March 1793 – 16 December 1864) was an English-born missionary for the Wesleyan Church in early colonial New Zealand, Australia, and Tonga.

Early life in England

Nathaniel was the fifth of seven children of Thomas and Elizabeth Turner. He was baptised on 10 March 1793, at the Anglican parish church of Wybunbury in Cheshire.[1] The family lived in a village just north of Wybunbury, called Hough, Cheshire. When the youngest son, Thomas, was eighteen months old, his mother died aged only 39. Eight months later their ten-year-old daughter Ann died, followed to the grave by their father Thomas on 7 April 1801, aged 41. The eldest of the orphans, Aaron, was only 16; Nathaniel only eight. They were brought up by friends and relatives in the village.[2]

Nathaniel was fostered by an uncle, and became involved with the local Methodist Church. Although brought up in the Church of England, he attended Wesleyan class-meetings and eventually, on 5 February 1812 “found peace with God”.[1] Soon after his conversion in 1812, Nathaniel began to preach and convert others. When the next Wesleyan circuit plan appeared, his local superintendent allotted him 42 appointments. He was not well received at home, and had to move to Blakenhall, a few miles south east of Wybunbury. He lived here with Thomas Salmon, where he studied, preached, and read the missionary intelligence reports from abroad. By March 1820 he was nominated for missionary service, but had to stay in England a while longer before funds could be found. He therefore began his mission at home, among the “sadly benighted and demoralised” villages in Cheshire and Staffordshire. He often met with opposition from the locals and Anglican priests alike, and was even physically attacked by the parish clerk in one village. Towards the end of 1821 he was instructed to prepare to depart for New Zealand by the Wesleyan Missionary Society (WMS).[1]

Just before leaving Cheshire, on 10 January 1822 he married Anne Sargent, daughter of John Sargent of Ipstones, Staffordshire.[2] Together they travelled to London, where Narthaniel was ordained on 23 January 1822.[3] Fellow missionary William White was ordained the same day.[1]

New Zealand Mission, 1823 to 1827

Voyage to Australia

On 23 January 1822 in London, Nathaniel was ordained; three weeks later he and Anne left England aboard the Deveron. It sailed on 15 February, bound for Van Dieman's Land (Tasmania) and then New South Wales. The 250 ton brig carried only 20 passengers, including the Reverend William White, whom the Methodist Missionary Society had sent to New Zealand along with the Turners. The ship nearly sank in the Bay of Biscay, and lost its rudder in a gale off the Cape of Good Hope.[1] They arrived at Tasmania after 124 days at sea; Anne was already pregnant, and gave birth to her first child, Ann Sargent Turner, in Hobart.[2]

Nathaniel had arrived only seven years after the first Methodist Missionary, Rev. Samuel Leigh, had landed in Tasmania, and only 34 years after the founding of the penal colony in New South Wales by the “First Fleet”. Leigh was replaced by Rev William Horton as Minister in Hobart in 1821 when Leigh was sent to New Zealand, and it was Horton who welcomed the Turner family.

On to New Zealand

Turner, who had been appointed to New Zealand, had to wait in Hobart several months as the Maori wars were raging across the land they were heading for. The Maori chief Hongi Hika had just returned from a trip to England, and had obtained firearms in Sydney on the way home. In the ruthless war that he started in North Island many rival Māori were killed and even eaten in Hongi's bid to become ultimate ruler. However, by April 1823 the war subsided, and Nathaniel set sail with his wife, and their baby daughter, for Sydney. Here he met up with John Hobbs, his companion for the New Zealand mission, and after ten weeks of preparation and consultation, set sail on The Brompton. They arrived at the Bay of Islands in north east New Zealand on 3 August 1823.[1]

Samuel Leigh had started the first Methodist Mission to New Zealand in 1822, and found a suitable place to establish their base at Wangaroa Bay - forty miles north of the Bay of Islands - which they called Wesleydale. By the time the Turners arrived a year later Leigh was “seriously invalided”. On arrival at the Bay of Islands Turner and Hobbs set off overland walking for three days to find Wangaroa and poor Mr Leigh. They returned to the Brompton in a chartered schooner to collect Mrs Turner, the baby, a nurse for the child, Miss Bedford, and their possessions.[4] On arrival back at Wangaroa, in the pouring rain, the Turners had to scrabble up the muddy bank to find the dismal house that was to be their home for the next three years.[1]

Wesleydale

Leigh and White had only been in Wesleydale for a few months before Turner and Hobbs arrived. Leigh left immediately, but White stayed on, to continue the work of establishing the first Wesleyan missionary station in New Zealand. After six months the missionaries began to teach the local children, and built a chapel that was consecrated in June 1824. Anne Turner had her second child, Thomas, in March 1924, born in Wesleydale.

Wesleydale was in the territory of the Ngāti Uru (or Ngatehure) iwi (or tribe) based in the Whangaroa area. One of the sons of the chief of the tribe, called Te Ara, had been the central figure in the Boyd Massacre. This had occurred in December 1809 when Māori of Ngāti Pou killed and ate between 66 and 70 European crew members from the British brigantine Boyd. Te Ara was known as George by the crew of the Boyd and by the missionaries of Wesleydale. After the death of his father, Te Ara became the chief of the Ngāti Uruiwi, and periodically threatened the missionaries and pilfered items from the Mission, as did his brother Te Puhi.

By early 1825 the relationship between the missionaries and the local Māori had begun to deteriorate. In March 1825, Turner was attacked and struck unconscious by Te Puhi, and a visiting whaling ship was plundered. Turner temporarily evacuated his wife and young children down to the Anglican mission in Kerikeri, some eight hours walk to the south. She returned to Wesleydale a few weeks later, after the death of Te Ara and the anticipated ‘prospect of tranquility’.

Later in 1825 William White left the Mission, to return to England; Rev Turner was then the only recognised ordained Wesleyan missionary in New Zealand. Along with John Hobbs and James Stack, the three completed the building of further houses, and expanded the area set aside for wheat growing. In May 1825 Anne Turner gave birth to their third child, Nathaniel Bailey, but he was to die eleven months later, and be buried in Wesleydale.[2]

Destruction of the Mission Station

In late 1826 Hongi Hika, the Chief who had visited England and had ambitions to conquer the whole area, was approaching Wesleydale - he sent word ahead for the local tribes to leave their food and fly for their lives. Eventually a three hundred strong war party entered Wesleydale and destroyed all the crops. Acting contrary to the orders of Hongi Hika, some of his Ngāpuhi warriors plundered Wesleydale on 9 January 1827, breaking into several outhouses. They threatened to return the following day. The Missionaries therefore decided to call for help, sending Stack to make his way overnight to the CMS mission in Kerikeri.[1]

By dawn on 10 January, the warriors returned, and smashed their way into the tool house, store rooms and eventually the main house. The missionaries had no option but to flee, and abandon Wesleydale. The group set off for the twenty mile walk to the CMS mission in Kerikeri: The Reverend Turner and his wife Anne; their three surviving children Anne (aged 3), Thomas (aged 2) and John Sargent (aged one month); their nanny Miss Davies; John Hobbs; Luke Wade and wife. They were accompanied by five boys and two girls from the Ngāti Uru Māori that had remained with the missionaries. “Mr. Turner, carrying his eldest son in his arms, with his dear wife and two other children, escaped only with their lives.”[5]

The group of sixteen walked all day, meeting help coming to their aid from Kerikeri, having been alerted by Stack. Further rescuers came from the CMS station in Paihia, and with their help the missionaries made it to Kerikeri by 7pm. After a night there, the group moved further from danger, heading by boat to the CMS mission station in Paihia. A few days later, they heard that the Wesleydale mission had been totally destroyed; the buildings burnt, the cattle killed, and the stores of wheat burnt. The Mission party eventually returned to Sydney, leaving New Zealand on 28 January 1827.[1]

Tonga Mission, 1827 to 1831

The Turners remained in Sydney for several months waiting for advice from London on where they should go to resume their missionary work. At last the Committee decided and they left Sydney for Tonga, to relieve the resident minister who was very ill. On 8 October 1827 they set sail on the eighty-ton schooner “Endeavor”. Nathaniel and Anne now had three children, and they were accompanied by Mr and Mrs Cross, Mr and Mrs Weiss and their three children, two European servants and three Maori children.[1]

As the previous missionaries had encountered a lot of trouble in Hihifo, Nathaniel decided to form the new station on another island in the Tonga group - Nukuʻalofa. The local chief was content, and gave them two local houses until they could build a permanent station. Turner set to learn the language, which was helped by his knowledge of Māori, and after a few weeks was able to preach a simple sermon, and write a Tongan hymn. By the end of the year Nathaniel had prepared an alphabet for the Tongan language, and had a first school book printed in Sydney for the missionaries to use in a school that was set up in March 1828. Numbers at the school rapidly increased, so they used the brighter pupils to teach the youngsters, and books were copied out in longhand. By the end of 1830 there were a thousand attending, and many other Tongans converted to Methodism.[1]

Turner's health began to weaken, so the WMS arranged for additional support from England. In early 1831 three new Missionaries arrived - one was a Turner from Cheshire, but no relation. A hurricane accompanied them, and devastated Tonga; a number of ships were wrecked in the harbour, but not those that brought the missionaries (which impressed the Tongans). The captain of one ship pleaded “if the Lord will only spare my vessel to me, I will never beat my wife again”. Nathaniel's health continued to decline, so the family left Tonga on the next available ship after the hurricane. They were seen off by their fellow missionaries and Tongan friends, and left the islands with great sadness, but content that they had done a good deal to convert the Tongans to Methodism. They sailed on the sloop of war “Comet” arriving in Sydney after a laborious six week voyage.[2]

The family stayed a while in Sydney, moving into the vacant Mission House in Parramatta and preaching there until the Missionary Society decided on their next posting. During this time one of the Turners’ infant children, George, died, having been weakened on the long crossing. But by the end of 1831 the Society had agreed that the Turners should return to Hobart: they sailed there on the “Argo” arriving on 24 November 1831.[1]

Tasmania Mission, 1831 to 1836

On his return to Tasmania from Sydney, Nathaniel had to make a number of journeys up to Launceston by horse. The 142 mile round trip was pretty rough going. In Launceston Nathaniel and his colleague John Manton were received by Isaac Sherwin,[6] a cousin of Anne Turner. Nathaniel would visit the various villages and stations en route, taking in a large circuit, and preaching to chain-gangs of convicts working on the roads. Meanwhile, Anne was left at home to bring up the ever-growing family.[1]

In early 1832 Nathaniel was away for two months to attend the District Meeting in Sydney again, and the family was afflicted with whooping cough. For two more years they carried on in Hobart, with Nathaniel regularly visiting Launceston. The church grew, and Nathaniel made more converts; he obtained land in Launceston to build a church, and preached to hundreds of settlers and convicts alike. On 20 July 1835 Anne gave birth to her ninth child - a girl they called Mary Emma Bloor Turner - Bloor after Mrs Turner's maternal grandmother. The girl was known as Emma, and was baptized on 6 September.[2]

By December 1835 Nathaniel had served four years in Hobart, and was sent by the Society to Sydney. By now he was 42, and his wife Anne 37; the baby Emma only five months old. However, on arrival in Sydney he was told that the Mission in New Zealand was in need of co-ordination and leadership.[1]

Return to New Zealand, 1836 to 1839

The problem with returning to New Zealand, as opposed to a spell in Sydney, was his children's education. Fortunately a Wesleyan local preacher recently arrived from England called James Buller[7] agreed to be the Turners’ tutor and accompany them to New Zealand. In April 1836 they sailed for New Zealand in the “Patriot” arriving on the West side of the Northland peninsula, twenty miles up the Hokianga River at a place called “Mangungu” - or “Broken to Pieces” in Māori.

Nathaniel visited the surrounding mission stations, including the Anglican ones, and the place he had been eight years before. He made a reconnaissance of the whole area to find the site for two new missions. On one such journey he was accompanied by his eldest son Thomas; they travelled down river to the mouth of the Hokianga to oversee the building of the new mission station. Nathaniel caught a fever while there, which made him delirious. In the boat home he was suddenly taken with a desire to throw himself overboard and drown: Thomas had to hold him back and keep him in the boat. Nathaniel raved on, and said he would never regain his sanity and spend the rest of his life in the lunatic asylum in Tasmania. But at least Nathaniel comforted himself in the knowledge that a friend of his, Dr Officer,[8] ran the place and would look after him. Thomas managed to get his demented father home, and kept in bed for several days.[1]

Once recovered he recommenced his preaching. The Māori language came back to him quickly, and he was soon fluent. He intervened in native quarrels, at one stage having to dodge the bullets of a rival clan. Nathaniel toured local villages, trying to heal the sick, preaching and teaching. In October 1837 Nathaniel and his fellow missionary, the Rev. John Whiteley, set off overland to the east coast to visit a number of villages and revisit Wesleydale; the place he had built up had returned to wilderness since he and his family fled for their lives a decade earlier in 1827.[1]

The following year disaster struck the Mangungu Mission. On 18 August 1838 the mission house burnt down: in his biography of his father, Josiah Turner wrote:

About two in the morning, on being awakened by a crackling noise, [Nathaniel] went to the sitting-room and found it full of smoke and flame. He alarmed the household, and then tried to re-enter the room, but was almost suffocated, and was driven back with his feet dreadfully burnt. The settlement was aroused by the chapel bell. Messrs Hobbs and Woon[9] and hundreds of natives were on the spot in a few minutes. The flames rapidly bursting through the roof, every effort was made to save whatever could be got out of the house. Mrs Turner had scarcely left her room for ten weeks but had strength given her to get the children and herself out of the burning building. Flakes of fire were already falling on Mr Hobbs house, a few yards distant. The children with their mother were now being carried in the arms of willing natives to Mr Woon’s house, out of reach of danger, when Mrs Turner would have them stop, that the children might be counted. One was missing, but it was not known from which family. Instant search was made in both houses, and in a bedroom on fire a little boy was found.[1]

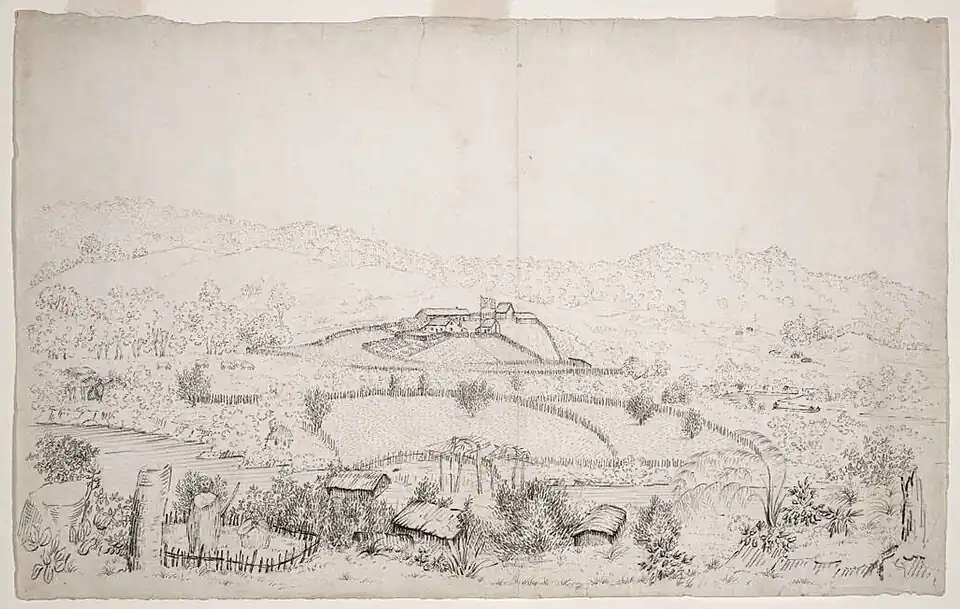

That boy was the author, Josiah. John Hobbs, now back at Māngungu Mission, had in his youth been an apprentice carpenter and set about building a replacement, assisted by volunteers from the European population in the area. Turner, who had taken over the running of the mission from White, moved into the new house the following year.[10] It was constructed with a rectangular floor plan having seven rooms, one of which was a large parlour, a pair of dormer windows and a verandah along the front.[11]

But ill health plagued Nathaniel, and it became time to leave New Zealand. With a family now of twelve all packed up, they sailed on 24 August 1839 for Sydney on the “Francis Spaight”. They arrived after a seventeen-day voyage.[1]

Tasmania again, 1839 to 1846

After a couple of months in Sydney the Committee appointed Nathaniel Chairman of the Van Diemans Land District, and sent him back to Hobart for the third time. In November 1839, after a nine-day voyage on the “Lord Glenelg” the family were back in their old house in Melville Street, Hobart.[1] Nathaniel's colleague in Hobart was the Rev John Eggleston [12] a Wesleyan minister born in Nottingham, who went on to become the President of the Australasian Conference, and to found Wesley College in Melbourne in 1866.

In November 1840 the TURNER family moved up to Launceston, leaving two sons in Hobart - one in a banking job and the other at school.[2] The Methodist Circuit in Launceston was very healthy: they had raised ten thousand pounds with which they built a Minister's residence, into which the Turner family later moved: “a spacious dwelling ... it is by far the best house we ever inhabited, and with our large family is a great comfort”.[1]

_-_Copy.jpg)

The description of the new premises [13]

The chapel is a neat brick building, sufficiently lofty to admit galleries, and cost £2,300. It stands on land given by the Local Government, under the administration of Governor Sir George Arthur. The foundation-stone was laid by Philip Oakden, Esq., April 20th, 1835, and it was opened for public worship on Christmas-day of the same year. The building on the right is the Minister's residence; that at the left is the day-school, in which the children of both sexes are educated. At the rear of the chapel, there is a room in which a Sunday-school and some of the week-evening services are conducted ; underneath which is a vestry, chapel-keeper’s residence, &c.

Over the next three years Nathaniel travelled the country around Launceston preaching and visiting. He made the long ride to Hobart several times for district meetings, and once to act as temporary General Superintendent of Missions. His fourteenth child was born while he was away on one trip in April 1842, only to die eight months later. These rides across country were not without incident: on one occasion his new horse, pulling a gig, kicked and plunged, threw Nathaniel out of the cart, and pulled the cart's wheel over him.[1]

In 1844 the Society sent the Turners from Launceston to New Norfolk, about 20 miles from Hobart. The day after they arrived Anne TURNER dreamt that she was in her old home in Ipstone in Staffordshire when she saw her father, John SARGENT, brought home very ill, and then die. Four months later the news came through that he had indeed died on that very day, in Ipstones. Nathaniel ploughed on in this unpromising town until 1846, when the new General Superintendent moved him to Sydney in a reshuffle of ministers.

Sydney Mission, 1846 to 1854

With the exception of the two eldest sons, who remained in Hobart working in banks, the whole Turner family sailed to Sydney on the “Lord Auckland” in September 1846. As they arrived the Turner children heard their names being shouted from a ship just behind, and ran to see Maori crewmen from the Hokianga tribe delighted to catch up with their old missionary and his family. Nathaniel continued with his ministry in Sydney, now aged 53. Over the years he was there, several schools were set up, churches at Surrey Hills and Chipendale were built, the main Wesleyan centre at York Street was enlarged, and the congregation increased through conversions and evangelism.[1]

The 1849 District Meeting appointed Nathaniel to the Circuit in Parramatta - a town a short distance in-land from Sydney. Methodism had had a hard time in this town, which had a reputation for “dull conservatism”; Nathaniel was the only Wesleyan minister, and had a wide area of scattered settlements around the town to cover. Once more, sickness affected him, and to rid himself of bronchitis he sailed for Melbourne, which was in the midst of its gold-rush. The trip did him little good - on the return leg the weather was so bad that his bronchitis returned, and he arrived home no better than when he left. His lungs were so damaged that he was unfit for work, and his health deteriorated further. The Parramatta congregation was also in decline, as many had set off for the ‘diggings’ in search of gold. In 1851 Nathaniel and his son Josiah made a 350-mile tour in a gig to see the gold-fields on a “ministerial visit of enquiry and observation”; as expected, the diggings were the scenes of vice. On their return they got lost in the bush, and eventually managed to find refuge in a shepherd's bark-hut where they were given mutton and damper, and a bed for the night. In return Nathaniel gave kindly words and prayers, and left a hymn book for the shepherd's “bright eyed little children”.[1]

But by the winter of 1852 he was forced by ill health to retire, and become a ‘supernumerary’ minister, and the family moved to the suburbs of eastern Sydney. The following year he accompanied Rev. Robert Young[14] from England and Rev. William Boyce[15] on a tour of inspection in the ship “Wesley” to New Zealand and Tonga; Nathaniel greatly enjoying the return to the places he had served in over his thirty-year career. They went on to Fiji where Nathaniel heard terrible stories of cannibalism, and inspected the works of the Wesleyan missionaries there. He returned to Sydney in 1854.[1]

Final Years in Brisbane, 1855 to 1864

By 1855 Nathaniel's second son, John Sargent Turner, and two daughters were living in Brisbane, which then had a population of only 2000; the warmer weather and cheaper living costs persuaded Nathaniel and Anne to join the rest of their family in Queensland. He bought an acre of land in the outskirts of Brisbane, and built a cottage there - the first house he actually owned himself.

During 1858 Nathaniel was again sick; his son Josiah visited from Sydney, and persuaded him to write his autobiography for the benefit of family and friends, and for young missionaries. Nathaniel reluctantly agreed, and set about writing from memory, and from Missionary Notices sent to London over the years, and then redistributed by the Society to all missionaries abroad. Josiah used this manuscript in writing his own book about his father - The Pioneer Missionary.[1]

Death and Burial

.jpg)

Nathaniel continued to be active in the church, when health permitted, and even, when aged 71, married his youngest daughter Louisa to William GRAHAM. But his health deteriorated further through 1864; he survived a gall-stone operation, but an attack of diarrhoea set in before he could fully recover, and he died on 16 December 1864, aged 71. In his last days he said to his wife “you cannot go with me over Jordan, but you can come to the brink; and when you leave me, Jesus will take me up. You must be brave! ‘Thy Maker is thine Husband’ ... you will soon follow me.”[1]

He was buried in a family grave at Toowong Cemetery, Brisbane.[16] His wife Anne lived on for a further 29 years. In her last years she lived with her son-in-law, Rev. John Harcourt, in Kew, Victoria. She died on 10 October 1893, aged 95, and was buried in the Crouch family plot in St Kilda Cemetery.[2]

Children

Nathaniel and Anne Turner had fourteen children and 80 grandchildren.[17]

- Ann Sargent, born in March 1823 in Hobart, died in 1900. She married Rev. John HARCOURT (1817–1893),[18] a much respected Wesleyan minister. They lived in Melbourne and had five children.

- Thomas, born March 1824, lived in Tasmania and died at sea on the way to see his father in 1852.

- Nathaniel Bailey, born in May 1825 in New Zealand but died in infancy in 1826. He was buried in the mission garden at Wesleydale, but his body was dug up by invading Maoris.

- John Sargent, born December 1826, died 1900. He married Adelaide BALL and had three sons: Leonard Haslewood[19] (1864–1906); Norman Harcourt (born and died 1866); and Leslie Mountford (1872–1953). Leonard's daughter Jean married Robert Hamilton Bruce Lockhart in 1913, but they divorced in 1938.

- Martha, born Tonga, August 1828, and died in 1905. She married William KENT, and lived on the Jondaryan Station in the Darling Downs in Queensland. They had 43 grandchildren from their 14 children: Mary; William;[20] Fassifern;[21] Walton;[22] Annie; Alice; Helen; Sydney;[23] Mabel; Irving;[24] Crofton;[25][26] Agnes; Martha; and Graham.

- Nathaniel, born October 1829, lived in Hobart and died 1910. He married Thirza Chipman HURST, and had four children: George; Annie; Jeanette; and Harry.

- George, born December 1830, died in infancy.

- Josiah George, born September 1832 in Hobart, lived in Maitland, NSW, and died in 1910. He was the author of his father's biography, and was ordained a Wesleyan Minister in 1858. He married Sarah OWEN, and had 13 children.

- Charles Wesley,[27] born April 1834, lived in Sydney and died in 1906. He married Emily IREDALE on 16 June 1857, on the same day as his younger sister's wedding. They had 13 children. From his second marriage to Ellen KEIG, Charles had two further children.

- Mary Emma Bloor, born July 1835 in Hobart and died on 12 October 1904 in St Kilda. She married Thomas James CROUCH, an architect, in Sydney on 16 June 1857, and had 12 children.

- Sarah Eliza Hopkins, born November 1836, married Henry JORDAN (1818–1890).[28] After a period in London as an Immigration Agent for Queensland, they lived in Brisbane. They had seven children.

- Hannah Jane, born in 1838 in Hokianga; died unmarried on 23 March 1907, and was buried in the CROUCH family plot with her mother and sister Emma.

- Louisa Elizabeth, born 1840, died 1914. She married William GRAHAM, and had nine children. GRAHAM was Scottish born, and was a farm manager and ‘squatter’ in the Darling Downs in Queensland, and represented the area in the Legislative Assembly until his death in 1892.

- Edwin, born April 1842, died in infancy.

Legacy

Reverend Nathaniel Turner was a significant figure in the history of Wesleyan missions in the Pacific, particularly in New Zealand and Tonga. His contributions had a lasting impact on the religious, cultural, and social landscapes of these regions. He was known for his respectful engagement with local cultures, which helped facilitate the acceptance of Christianity among indigenous populations. This approach fostered a more harmonious relationship between missionaries and local communities.

A street in the New Zealand village of Kaeo is named after him, in recognition of his key role in the establishment of the Wesleydale mission.

He left 14 children and 80 grandchildren, many of whom went on to have successful lives in Australia and New Zealand, as preachers, farmers, politicians and soldiers.

His obituary includes this assessment: ”Mr. Turner was emphatically a ‘good man’. Of him it could be said, as of Nathaniel of old, he was a man ‘in whom there was no guile’.” [5]

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z Turner, Josiah George (1872). The Pioneer Missionary: Life of the Rev. Nathaniel Turner. George Robertson, Melbourne and Wesleyan Conference Office, London.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Barry, T (1998). Seven Families South. Rheidol Press, London. ISBN 0 9532685 0 0.

- ^ "38 Wesleyan Missionaries b4 1840 - Wesley Historical Society Proceedings". John Kinder Theological Library. Retrieved 29 July 2025.

- ^ Colwell, James (1904). The illustrated history of Methodism. Australia: 1812-1855. New South Wales and Polynesia: 1856 to 1902. With special chapters on the discovery and settlement of Australia, the missions to the South Sea Islands, New Zealand and the aborigines, and a review of the movement leading up to Methodist union. Compiled from official records and other sources. University of California Libraries. Sydney : W. Brooks.

- ^ a b "THE REV. NATHANIEL TURNER". Queensland Daily Guardian. 17 December 1864. p. 6. Retrieved 30 July 2025.

- ^ Fysh, Ann, "Isaac Sherwin (1804–1869)", Australian Dictionary of Biography, Canberra: National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, retrieved 29 July 2025

- ^ "James Buller, b. 1812". National Portrait Gallery people. Retrieved 29 July 2025.

- ^ "Sir Robert Officer (1800–1879)", Australian Dictionary of Biography, Canberra: National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, retrieved 29 July 2025

- ^ "William Woon". natlib.govt.nz. Retrieved 29 July 2025.

- ^ Adams, Patricia; Ross, R. M. (1983). "Hokianga Homes of Missionary, Magistrate and Pakeha Maori". Historic Buildings of New Zealand: North Island. Auckland: Methuen Publications. pp. 22–23. ISBN 0-456-03110-3.

- ^ Gatley, Julia. "Domestic Architecture: Mangungu Mission House". Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Ministry for Culture & Heritage. Retrieved 30 July 2022.

- ^ Howe, Renate, "John Eggleston (1813–1879)", Australian Dictionary of Biography, Canberra: National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, retrieved 29 July 2025

- ^ Wesleyan Methodist Missionary Society (1855). Wesleyan Juvenile Offering: A Miscellany of Missionary Information for Young ... Oxford University. [Wesleyan Missionary Society].

- ^ Claughton, S. G., "Robert Young (1796–1865)", Australian Dictionary of Biography, Canberra: National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, retrieved 29 July 2025

- ^ Claughton, S. G., "William Binnington Boyce (1804–1889)", Australian Dictionary of Biography, Canberra: National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, retrieved 29 July 2025

- ^ "THE LATE REV. N. TURNER". Brisbane Courier. 7 December 1864. p. 2. Retrieved 30 July 2025.

- ^ Turner, Reginald (1961). Rev Nathaniel TURNER - Male Issue and Descendants.

- ^ "Rev. John Harcourt". companyofangels.net. Retrieved 29 July 2025.

- ^ "DEATH OF MAJOR TURNER". Brisbane Courier. 8 September 1906. p. 9. Retrieved 30 July 2025.

- ^ "Former Member Details | Queensland Parliament". www.parliament.qld.gov.au. Retrieved 29 July 2025.

- ^ "Biography - Fassifern Kent - People Australia". peopleaustralia.anu.edu.au. Retrieved 29 July 2025.

- ^ "PASSING OF THE PIONEERS". Queenslander. 25 August 1923. p. 34. Retrieved 31 July 2025.

- ^ "Family Notices". Brisbane Courier. 25 August 1898. p. 4. Retrieved 31 July 2025.

- ^ "The Late Mr Irving Kent". 22 July 1899. p. 203. Retrieved 31 July 2025.

- ^ "Kent—M'Lellan". Queenslander. 20 April 1901. p. 795. Retrieved 31 July 2025.

- ^ "LATE MR. CROFTON KENT". Toowoomba Chronicle and Darling Downs Gazette. 27 April 1932. p. 5. Retrieved 31 July 2025.

- ^ "TURNER, Charles Wesley | Te Ara Encyclopedia of New Zealand". teara.govt.nz. Retrieved 30 July 2025.

- ^ Morrison, A. A., "Henry Jordan (1818–1890)", Australian Dictionary of Biography, Canberra: National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, retrieved 29 July 2025

Further reading

- The main reference source for the life of Nathaniel Turner is The Pioneer Missionary: Life of the Rev. Nathaniel Turner accessible at Archive.org here [1]