Narciso Yepes

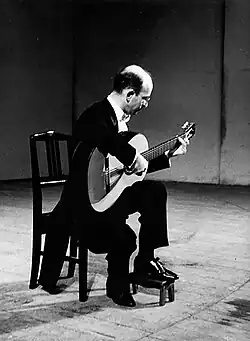

Narciso Yepes (14 November 1927 – 3 May 1997) was a Spanish guitarist. He is considered one of the finest virtuoso classical guitarists of the twentieth century.[1]

Biography

Yepes was born into a family of humble origin in Lorca, Region of Murcia. His father gave him his first guitar when he was four years old, and took the boy five miles on a donkey to and from lessons three days a week. Yepes took his first lessons from Jesús Guevara, in Lorca. Later his family moved to Valencia when the Spanish Civil War started in 1936.

When he was 13, he was accepted to study at the Conservatorio de Valencia with the pianist and composer Vicente Asencio. Here he followed courses in harmony, composition, and performance. Yepes is credited by many with developing the A-M-I technique of playing notes with the ring (Anular), middle (Medio), and index (Indice) fingers of the right hand.[2] Guitar teachers traditionally taught their students to play by alternating the index and middle fingers, or I-M. However, since Yepes studied under teachers who were not guitarists, they pushed him to expand on the traditional technique. According to Yepes, Asencio "was a pianist who loathed the guitar because a guitarist couldn't play scales very fast and very legato, as on a piano or a violin. 'If you can't play like that,' he told me, 'you must take up another instrument.'" Through practice and improvement in his technique, Yepes could match Asencio's piano scales on the guitar. "'So,' he [Asencio] said, 'it's possible on the guitar. Now play that fast in thirds, then in chromatic thirds.'"[3] Allan Kozinn observed that, "Thanks to Mr. Asencio's goading, Mr. Yepes learned "to play music the way I want, not the way the guitar wants."[4] Similarly, the composer, violinist, and pianist George Enescu would also push Yepes to improve his technique, which also allowed him to play with greater speed.[5]

On 16 December 1947 he made his Madrid début, performing Joaquín Rodrigo's Concierto de Aranjuez with Ataúlfo Argenta conducting the Spanish National Orchestra. The overwhelming success of this performance brought him renown from critics and public alike. Soon afterwards, he began to tour with Argenta, visiting Switzerland, Italy, Germany, and France. During this time he was largely responsible for the growing popularity of the Concierto de Aranjuez, and made two early recordings, both with Argenta[6] – one in mono with the Madrid Chamber Orchestra (released between 1953 and 1955),[7] and the second in stereo with the Orquesta Nacional de España (recorded in 1957 and released in 1959).[8]

In 1950, after performing in Paris, he spent a year studying interpretation under the violinist George Enescu, and the pianist Walter Gieseking. He also studied informally with Nadia Boulanger. This was followed by a long period in Italy where he profited from contact with artists of every kind.

On 18 May 1951, as he leant on the parapet of a bridge in Paris and watched the Seine flow by, Yepes unexpectedly heard a voice inside him ask, "What are you doing?" He had been a nonbeliever for 25 years, perfectly content that there was no God or transcendence or afterlife. But that existential question, which he understood as God's call, changed everything for him. He became a devout Catholic, which he remained for the rest of his life.[9]

In 1952 a work ("Romance"), Yepes claims to have written when he was a young boy,[10] became the theme to the film Forbidden Games (Jeux interdits) by René Clément.

Despite Yepes's claims of composing it, the piece ("Romance") has often been attributed to other authors; indeed published versions exist from before Yepes was even born, and the earliest known recording of the work dates from a cylinder from around 1900.[11][12][13] In the credits of the film Jeux Interdits, however, "Romance" is credited as "Traditional: arranged – Narciso Yepes." Yepes also performed other pieces for the Forbidden Games soundtrack. His later credits as film composer include the soundtracks to La Fille aux yeux d'or (1961) and La viuda del capitán Estrada (1991). He also starred as a musician in the 1967 film version of El amor brujo.

In Paris he met Maria Szumlakowska, a young Polish philosophy student, the daughter of Marian Szumlakowski, the Ambassador of Poland in Spain from 1935 to 1944. They married in 1958 and had two sons, Juan de la Cruz (deceased), Ignacio Yepes, an orchestral conductor and flautist, and one daughter, Ana Yepes, a dancer and choreographer.[14]

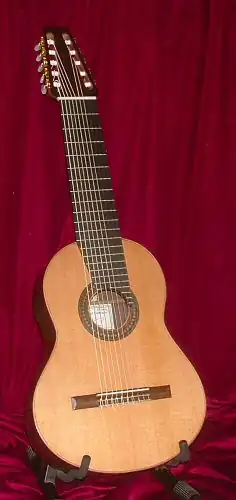

In 1964, Yepes performed the Concierto de Aranjuez with the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra, premièring the ten-string guitar, which he invented in collaboration with the renowned guitar maker José Ramírez III.[15]

The instrument made it possible to transcribe works originally written for baroque lute without deleterious transposition of the bass notes. However, the main reason for the invention of this instrument was the addition of string resonators tuned to C, B♭, A♭, F#, which resulted in the first guitar with truly chromatic string resonance – similar to that of the piano with its sustain/pedal mechanism.

After 1964, Yepes used the ten-string guitar exclusively, touring all six inhabited continents, performing in recitals as well as with the world's leading orchestras, giving an average of 130 performances each year. He recorded the Concierto de Aranjuez for the first time with the ten-string guitar in 1969 with Odón Alonso conducting the Orquesta Sinfonica R.T.V. Española.

Apart from being a consummate musician, Yepes was also a significant scholar. His research into forgotten manuscripts of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries resulted in the rediscovery of numerous works for guitar or lute. He was also the first person to record the complete lute works of Bach on period instruments (14-course baroque lute). In addition, through his patient and intensive study of his instrument, Narciso Yepes developed a revolutionary technique and previously unsuspected resources and possibilities.

He was granted many official honours including the gold medal for Distinction in Arts, conferred by King Juan Carlos I; membership in the academy of "Alfonso X el Sabio" and an Honorary Doctorate from the University of Murcia. In 1986 he was awarded the Premio Nacional de Música of Spain, and he was elected unanimously to the Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando.[16]

In the 1980s, Yepes formed Trio Yepes with his son Ignacio Yepes on flute and recorder and his daughter Ana dancing to her own choreography.

After 1993, Narciso Yepes limited his public appearances due to illness. He gave his last concert on 1 March 1996 in Santander (Spain).

He died in Murcia in 1997, after a long battle with lymphoma.

Press quotes

As one writer has observed, "His [Yepes's] taking advantage of the instrument's flexibility has opened Yepes to some criticism," citing Bach's Chaconne in D Minor as an example. Yepes responded that, "There are three versions of the Chaconne and I analyzed all three. The version I play is the one I think Bach would have written if he'd composed the piece for guitar or lute."[4]

Guitarist and teacher Ivor Mairants noted that after a Yepes concert at Wigmore Hall in 1961, some in the audience were split about Yepes's phrasing. Mairants, who had started as a jazz guitarist but took up the classical guitar and had two lessons with Segovia, met with Yepes afterwards and questioned him about his phrasing, which was very different from Segovia's. In his memoir, Mairants wrote, "I exclaimed 'Do you think it necessary to play that section (of Villa Lobos' Prelude No. 1) as slowly as you do?' 'Why, yes' he (Yepes) said, 'Look at the paper (music) and you will see it written that way'. When I again mentioned that Segovia did not play it that way, he had no doubt had enough of my comparisons and answered, somewhat heatedly 'I have a great admiration for Segovia and everything he has done for the guitar and its history, but I do not have to put on a record of Segovia and play the music exactly as he does. No, I don't think so!'"[17] Elsewhere, Yepes was quoted as saying, "Segovia is a very beautiful player, but it is not necessary to imitate him. Why should Rostropovich imitate Casals?"[4]

Recordings (partial)

Recordings at Deutsche Grammophon Gesellschaft

- "La Fille aux Yeux d'Or" (original film soundtrack) (Fontana, 460.805)

- "Narciso Yepes: Bacarisse/Torroba" (Concertos) (London, CCL 6001)

- "Jeux Interdits" (Original film soundtrack) (London, Kl 320)

- "Narciso Yepes: Recital" (London, CCL 6002)

- "Falla/Rodrigo" (Concierto de Aranjuez) (London, CS 6046)

- "Spanish Classical Guitar Music" (London, KL 303)

- "Vivaldi/Bach/Palau" (Conciertos & Chaconne)(London, CS 6201)

- "Guitar Recital: Vol. 2" (London, KL 304)

- "Rodrigo/Ohana" (Concertos) (London, CS 6356)

- "Guitar Recital: Vol. 3" (London, KL 305)

- "The World of the Spanish Guitar Vol. 2" (London, STS 15306)

- "Simplemente" (re-release of early recordings) (MusicBrokers, MBB 5191)

- "Guitar Music of Spain" (LP Contour cc7584)

- "Recital Amerique Latine & Espagne" (Forlane, UCD 10907)

- "Les Grands d'Espagne, Vol. 4" (Forlane, UM 3903)

- "Les Grands d'Espagne, Vol. 5" (Forlane, UM 3907)

- "Fernando Sor – 24 Etudes" (Deutsche Grammophon, 139 364)

- "Spanische Gitarrenmusik aus fünf Jahrhunderten, Vol. 1" (Deutsche Grammophon, 139 365)

- "Spanische Gitarrenmusik aus fünf Jahrhunderten, Vol. 2" (Deutsche Grammophon, 139 366)

- "Joaquín Rodrigo: Concierto de Aranjuez, Fantasía para un Gentilhombre" (Deutsche Grammophon, 139 440)

- "Rendezvous mit Narciso Yepes" (Deutsche Grammophon, 2538 106)

- "Luigi Boccerini: Gitarren-Quintette" (Deutsche Grammophon, 2530 069 & 429 512–2)

- "J.S. Bach – S.L. Weiss" (Deutsche Grammophon, 2530 096)

- "Heitor Villa-Lobos" (Deutsche Grammophon, 2530 140 & 423 700–2)

- "Música Española" (Deutsche Grammophon, 2530 159)

- "Antonio Vivaldi" (Concertos) (Deutsche Grammophon, 2530 211 & 429 528–2)

- "Música Catalana" (Deutsche Grammophon, 2530 273)

- "Guitarra Romantica" (Deutsche Grammophon, 2530 871)

- "Johann Sebastian Bach: Werke für Laute" (Works for Lute – Complete Recording on Period Instruments) (Deutsche Grammophon, 2708 030)

- "Francisco Tárrega" (Deutsche Grammophon, 410 655–2)

- "Joaquín Rodrigo" (Guitar Solos) (Deutsche Grammophon, 419 620–2)

- "Romance d'Amour" (Deutsche Grammophon, 423 699–2)

- "Canciones españolas I" (Deutsche Grammophon, 435 849–2)

- "Canciones españolas II" (Deutsche Grammophon, 435 850–2)

- "Rodrigo/Bacarisse" (Concertos) (Deutsche Grammophon, 439 5262)

- "Johann Sebastian Bach: Werke für Laute" (Works for Lute – Recording on Ten-String Guitar) (Deutsche Grammophon, 445 714–2 & 445 715–2)

- "Johann Sebastian Bach: Werke für Laute II" (Works for Lute II – Recording on Ten-String Guitar) (Deutsche Grammophon 1974, 2530 462)

- "Rodrigo/Halffter/Castelnuovo-Tedesco" (Concertos) (Deutsche Grammophon, 449 098-2)

- "Domenico Scarlatti: Sonatas" (Deutsche Grammophon, 457 325–2 & 413 783–2)

- "Guitar Recital" (Deutsche Grammophon, 459 565–2)

- "Asturias: Art of the Guitar" (Deutsche Grammophon, 459 613–2)

- "Narciso Yepes" (Collectors Edition box set) (Deutsche Grammophon, 474 667–2 to 474 671–2)

- "20th Century Guitar Works" (Deutsche Grammophon)

- "Guitar Music of Five Centuries" (Deutsche Grammophon)

- "G.P. Telemann" (Duos with Godelieve Monden) (Deutsche Grammophon)

- "Guitar Duos" (with Godelieve Monden) (BMG)

- "Leonardo Balada: Symphonies" ('Persistencies') (Albany, TROY474)

- "The Beginning of a Legend: Studio Recordings 1953/1957" (Istituto Discografico Italiano, 6620)

- "The Beginning of a Legend vol. 2: Studio Recordings 1960" (Istituto Discografico Italiano, 6625)

- "The Beginning of a Legend vol. 3: Studio Recordings 1960/1963" (Istituto Discografico Italiano, 6701)

Works composed for or dedicated to Narciso Yepes (partial)

- Estanislao Marco: Guajira

- Joaquín Rodrigo: En los trigales (1939) [Since Yepes was only 12 years old when Rodrigo wrote En los trigales, it is unlikely that it was written for Yepes. It was likely dedicated to him in the 1950s, when Rodrigo included it and two other pieces as the suite Por los campos de España.]

- Manuel Palau: Concierto levantino

- Manuel Palau: Ayer

- Manuel Palau: Sonata

- Salvador Bacarisse: Concertino in A-minor

- Salvador Bacarisse: Suite

- Salvador Bacarisse: Ballade

- Maurice Ohana: Tiento (1955)

- Maurice Ohana: Concerto "Trois Graphiques" (1950–7)

- Maurice Ohana: Si le jou paraît... (1963)

- Cristóbal Halffter: Codex 1 (1963)

- Leo Brouwer: Tarantos

- Alcides Lanza: Modulos I (1965)

- Leonardo Balada: Guitar Concerto No. 1 (1965)

- Antonio Ruiz-Pipó: Cinqo Movimientos (1965)

- Antonio Ruiz-Pipó: Canciones y Danzas (1961)

- Leonardo Balada: Analogías (1967)

- Leon Schidlowsky: Interludio (1968)

- Eduardo Sainz de la Maza: Laberinto (1968)

- Antonio Ruiz-Pipó: "Tablas" Concerto (1968–69/72)

- Vicente Asencio: Collectici íntim (1970)

- Vicente Asencio: Suite de Homenajes

- Bruno Maderna: Y después (1971)

- Leonardo Balada: "Persistencias" Sinfonía-concertante (1972)

- Jorge Labrouve: Enigma op. 9 (1974)

- Jorge Labrouve: Juex op. 12 (Concertino) (1975)

- Luigi Donorà: Rito (1975)

- Tomás Marco: Concierto "Eco" (1976–78)

- Francisco Casanovas: La gata i el belitre

- Miguel Ángel Cherubito: Suite popular Argentina

- José Peris: Elegía

- Xavier Montsalvatge: Metamorfosis de Concierto (1980)

- Jean Françaix: Concerto pour guitare et orchestre à cordes (1982)

- Xavier Montsalvatge: Fantasía para guitarra y arpa (1983)

- Federico Mompou: Canço i dansa no. 13

- Alan Hovhaness: Concerto No. 2 for Guitar and Strings, Op. 394 (1985)

- María de la Concepción Lebrero Baena: Remembranza de Juan de la Cruz (1989)

References

- ^ Woodstra, Chris; Brennan, Gerald; Schrott, Allen, eds. (2005). All Music Guide to Classical Music: The Definitive Guide to Classical Music. Backbeat Books. p. 1526. ISBN 0-87930-865-6.

- ^ ""Fritz Buss Interview: Narciso Yepes, as I Knew Him," 2004".

- ^ Williams, Roger M. (April 1985). Connoisseur. pp. Vol. 215 p.148.

10: Narciso Yepes is Not Only a Virtuoso; He Invented a New Sound for the Guitar

- ^ a b c Kozinn, Allan (22 November 1981). "Narciso Yepes and His 10-String Guitar". The New York Times, D21.

- ^ ""Fast Scales With 'ami,'" Douglas Niedt's Guitar Technique Tip of the Month" (PDF).

- ^ "The Spanish Legacy of Ataúlfo Argenta".

- ^ The World's Encyclopaedia of Recorded Music. January 1953. pp. Supplement III.

- ^ "Narciso Yepes and the Concierto de Aranjuez". 23 August 2009.

- ^ Urbano, Pilar (January 1988). "Interview with Narciso Yepes (in Spanish)". Época, no. 147.

- ^ "Narciso Yepes speaks on Forbidden Games Romance". 26 January 2009. Retrieved 9 August 2012 – via YouTube.

- ^ Viuda de Aramburo, Madrid (Príncipe, 12), alt.

- ^ another newspaper clipping

- ^ Early Spanish Cylinders and the Viuda de Aramburo Company (Carlos Martín Ballester – publications)

- ^ "Compagnie Ana Yepes". Anayepes.com. Archived from the original on 10 August 2020. Retrieved 9 August 2012.

- ^ Ramirez III, Jose (1994), "The Ten-String Guitar" in Things About the Guitar, Bold Strummer, pp. 137–141, ISBN 8487969402

- ^ "narciscoyepes.org". narcisoyepes.org. Retrieved 27 November 2015.

- ^ Mairants, Ivor (1980). My Fifty Fretting Years: A Personal History of the Twentieth Century Guitar Explosion. Ashley Mark Publishing Co. p. 286.

External links

- International Jose Guillermo Carrillo Foundation

- Official Homepage www.narcisoyepes.org

- Biography Archived 1 June 2007 at the Wayback Machine (Conservatorio de Música "Narciso Yepes" Lorca (Murcia) España Archived 16 April 2007 at the Wayback Machine)

- Biography by Robert Cummings (Allmusic)

- Information (Región de Murcia Digital) (in Spanish)

- Biography (Guitarreando) (in Spanish)

- Biography (A.MA.MUS. es una Asociación de Maestros de Música) (in Spanish)

- Information (Esperanto)

- Narciso Yepes receiving Doctores Honoris Causa Archived 14 February 2012 at the Wayback Machine at Universidad de Murcia (audio Archived 5 February 2012 at the Wayback Machine)

- Entrevista Con Narciso Yepes (includes audio interview) by Manuel Segura; Murcia, February 1988 (in Spanish)

- αφιέρωμα για τα 80 χρόνια από τη γέννηση του Narciso Yepes (Tar) (in Greek)

- Narciso Yepes at IMDb

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TWJfF0XegAw Narciso Yepes explains his authorship of the Romance

- www.tenstringguitar.info Archived 1 December 2017 at the Wayback Machine Site about the authentic Yepes ten-string guitar

Articles

- Narciso Yepes en el recuerdo by Antonio Díaz Bautista (laverdad.es) (in Spanish)

- Narciso Yepes y su legado olvidado (laverdad.es) (in Spanish)

Recordings

- Recordings at Deutsche Grammophon Gesellschaft

- Some photos of LP covers (Oviatt Library Digital Collections)

- Joaquín Rodrigo – Concierto de Aranjuez by Narciso Yepes