Music of the Democratic Republic of the Congo

| General topics | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genres | ||||

| Media and performance | ||||

|

||||

| Nationalistic and patriotic songs | ||||

|

||||

| Regional music | ||||

|

||||

Congolese music is one of the most influential music forms of the African continent. Since the 1930s, Congolese musicians have had a huge impact on the African musical scene and elsewhere. Many contemporary genres of music, such as Kenyan benga and Colombian champeta, have been heavily influenced by Congolese music. In 2021, Congolese rumba joined the UNESCO list of intangible cultural heritage.[1][2]

Prior to the emergence of Congolese rumba, the country's musical scene was dominated by folkloric traditions rooted in oral transmission and communal performance.[3] Ethnic associations in urban centers performed using traditional instruments such as the tam-tam (known as mbunda in Lingala and ngoma in many Bantu languages), patenge (a small, skin-covered frame drum), likembe or sanza (thumb piano), lokole, ngomi or lindanda (a gourd-resonated guitar), madimba or balafon, londole, kisakasaka, and others.[3][4] This traditional music was characterized by rhythmic complexity, polyrhythmic percussion, the pentatonic scale, collective polyphonic singing, improvisation, vocal exclamations, handclapping, and dance.[3]

The urbanization of Léopoldville (now Kinshasa) in the 1930s and the expansion of colonial commercial enterprises introduced Congolese populations to a broad spectrum of foreign musical styles, including Cuban rumba, jazz, blues, biguine, highlife, and bolero.[3] These influences contributed to a gradual shift away from purely folkloric traditions.[3] Among the key transitional genres was maringa, a Kongo partner dance originating in the former Kingdom of Loango, which flourished in the bar-dancing culture of Brazzaville and Léopoldville.[5][6][7][8][9] Early performances incorporated instruments such as the bass drum, accordion (likembe), and glass bottles used as percussion.[10][11] During the 1940s and 1950s, the arrival of Cuban son recordings played a major role in maringa's transformation into "Congolese rumba", as works by groups like Sexteto Habanero, Trio Matamoros, and Los Guaracheros de Oriente were frequently marketed as "rumba".[12][13]

The modern character of Congolese music was reflected in its adoption of electric instruments, innovative performance aesthetics, commercial appeal, and its emergence as a powerful expression of national identity.[14] This transition brought about a decline in the use of traditional instruments and vernacular languages, with modern tools such as the electric guitar, saxophone, and accordion gaining prominence, and Lingala emerging as the dominant language of popular music.[3][15] The new music adopted various names, including zebola, agwaya, nzango, kebo, Polka Piké, and, most notably, Congolese rumba.[3] Despite the increasing dominance of modern sounds, certain musicians maintained ties to traditional styles.[3] During the 1960s and 1970s, Congolese rumba gave birth to a wave of innovative popular dance styles, including soukous, a high-tempo genre characterized by intricate guitar melodies and layered polyrhythms.[16][17] In the late 1990s, ndombolo, an offshoot of soukous known for its high-energy dance, also rose to continental prominence.[18][19][20][21] Throughout this evolution, Congolese people have not adopted a singular term for their music. Historically referred to as muziki na biso ("our music"), the most common term today is ndule, meaning "music" in Lingala.[22][23] The term rumba or rock-rumba is also used generically to refer to Congolese music, though neither is precise nor accurately descriptive.[22]

History

Colonial times (pre-1960)

Since the colonial era, Kinshasa, Congo's capital, has been one of the great centers of musical innovation. The country, however, was carved out from territories controlled by many different ethnic groups, many of which had little in common with each other. Each maintained (and continue to do so) their own folk music traditions, and there was little in the way of a pan-Congolese musical identity until the 1940s.

In both the former French Congo and Belgian Congo (modern-day Republic of the Congo and Democratic Republic of the Congo), the popular partnered dance music was initially known as maringa. This dance originated among the Kongo people within the historical Kingdom of Loango, encompassing present-day areas of the Republic of the Congo, southern Gabon, and Angola's Cabinda Province.[24][25] Maringa utilized a combination of traditional instruments such as the patengé (a small frame drum), a glass bottle used as a triangle, and a variant of the likembe (a thumb piano) with steel reeds.[24] The dance was characterized by a rhythmic swaying of the hips, alternating weight from leg to leg, and was stylistically reminiscent of the Afro-Cuban rumba. By the 1930s, partnered dance had become widespread throughout the Congo region.[24] According to ethnomusicologist Kazadi wa Mukuna, early recording studios began to market maringa as "rumba", blending in the newer rumba rhythm while keeping the original name.[26] Scholar Phyllis Martin also noted that the interest of the White elite in Brazzaville in Latin American music—especially after Cuban rumba's exposure at the 1932 Chicago World's Fair—played a significant role in this transition.[24] Nonetheless, both colonial and African elites often favored dances like the tango and the biguine. In 1934, Jean Réal, a French director of entertainment from Martinique, coined the term "Congo Rumba" when he founded a band of the same name in Brazzaville in 1938.[24][27][28] Several institutions key to the development of Congolese popular music were established soon thereafter: Olympia and its associated labels (Novelty, Kongo Bina, and Lomeka) were founded in 1939 by Fernand Jansens and Albert Patou; Studio Congolia, affiliated with Radio Congolia, was created in 1941 by Jean Hourdebise.[29] In August of 1941, Congolese musicologist Emmanuel Okamba documented the formation of Victoria Brazza, an ensemble led by Paul Kamba in Poto-Poto, Brazzaville. Their performances blended the traditional maringa rhythm with modern instrumentation, including accordion, guitar, mandolin, and banjo, creating what would become known as modern Congolese rumba—a fusion of programmable modern sounds with the intuitive, non-programmable textures of traditional instruments.[30]

A similar development occurred in Kinshasa, where vocalist Antoine Wendo Kolosoy formed the group Victoria-Kin in 1943. His ensemble employed instruments such as the patenge, the mukwasa (a scraper), and a bass drum. Wendo, renowned along the Congo River, performed with up to 15 choristers, including his cousin Léon Yangu Mbale.[29] His work inspired Henri Bowane, born in Mbandaka to a Congolese father from Brazzaville, who briefly formed the vocal group Victoria-Coquilathville before settling in Kinshasa on 25 December 1949. Bowane played a central role in the promotion of Kinshasa's evolving rumba style, particularly following the founding of key recording companies such as Ngoma (by John Nicolas Jeronimidis) and Kina (by Gabriel Benatar) in 1948.[29] Simultaneously, Cuban son music—performed by groups like Sexteto Habanero, Trio Matamoros, and Los Guaracheros de Oriente—was broadcast on Radio Congo Belge in Kinshasa. Musicians adapted Cuban son's instrumentation—piano, percussion, and brass—by transposing these elements onto electric guitars and saxophones, sometimes singing in phonetic Spanish or French.[31][32][33] Over time, Congolese artists began incorporating indigenous rhythms and melodic structures.[33] Notably, the term "Congolese rumba" emerged due to the mislabeling of Cuban records as "rumba" by importers.[26] According to Kazadi wa Mukuna, Congolese rumba was not a direct adaptation of Cuban dance forms, but rather a reinterpretation of the name and instrumentation, ultimately returning to maringa's rhythmic foundations.[34] He argued that the name "rumba" was retained primarily for commercial appeal, while musicians gravitated back to patterns that could be more readily integrated with newly acquired instruments and aligned with traditional music and dance structures.[34]

Before the establishment of formal bands, early Congolese music was dominated by solo singers, such as Antoine Wendo Kolosoy, Henri Bowane, Léon Bukasa, Antoine Kasongo Kitenge, Camille Feruzi, Adou Elenga, Baudouin Mavula, Jean Bosco Mwenda wa Bayeke, Baba Gaston, Kabongo Paris, and Manoka Desaïo.[29] On the female front, pioneering artists between 1951 and 1959 included Lucie Eyenga (considered the first woman in sub-Saharan Africa to record music), Tekele Mokango, Anne Ako, the duos Esther Sudila & Léonine Mbongo, Jeanne Ninin & Caroline Mpia, as well as Marie Kitoto, Albertine Ndaye, Martha Badibala, Pauline Lisanga, and Marcelle Ebibi—the latter being Cameroonian-born and married to Guy-Léon Fylla of Brazzaville.[29]

Following World War II, a group of coastal West Africans—referred to locally as the Popo and placed below Europeans and métis (mixed-race) in the colonial social hierarchy—settled in the Belgian Congo as accountants and administrators. To occupy their leisure time, they formed the Excelsior Orchestra in Boma.[29] This group was modeled on Ghana's Excelsior of Accra (founded in 1914 by Franck Torto) and performed on weekends in rudimentary bars and public spaces.[29] Their repertoire included maringa and highlife played on European instruments such as guitar, saxophone, chromatic accordion, trumpet, and piano. According to Bowane, this group later gave rise to a second formation, Jazz Popo, which served as a significant influence on emerging Congolese musicians.[29]

In 1942, historian Kanza Matondo records the formation of three Congolese brass orchestras: Odéon, led by Kabamba and Booth; Américain, under the leadership of brothers Alex and André Tshibangu; and Martinique, founded by Kasongo, Fernandès, Booth, and Malonga. These ensembles marked the advent of Congolese group-based music initiatives.[29] Jean-Pierre François Nimy Nzonga, Mfumu Fylla Saint-Eudes, and several online sources document additional vocal and brass ensembles active during the 1940s. Chief among them was Odéon Kinois, comprised largely of alumni from the Boma Colonial School (Colonie Scolaire de Boma).[29] This group was led by Justin Disasi, a playwright who would later become the elected mayor of Kalamu in 1956. The initiative stemmed from Eugène Kabamba, a civil servant in the Ministry of Finance and President of the Assanef (Association des anciens élèves des Frères des écoles chrétiennes).[29] In 1947, Disasi assumed leadership of the orchestra Melo Kin, a Kinshasa-based successor to Melo Congo, originally founded in Brazzaville by saxophonist Emmanuel Dadet. Disasi's tenure at Odéon Kinois concluded that same year when he was succeeded by trumpeter René Kisumuna, a fellow alumnus of the Boma school.[29] Odéon Kinois, then regarded as a leading ensemble, faced growing competition from other orchestras, including Américain and splinter groups led by musicians such as Antoine Kasongo Kitenge and Jean Lopongo. Lopongo's group eventually performed at Siluvangi Bar, a venue previously associated with Camille Feruzi's orchestra.[29]

Odéon Kinois—most commonly linked to Disasi—should not be conflated with the similarly named ensemble founded by Kabamba and Booth, nor with Odéon Vocal, led by Léon Yayu and Mulangi. All three formations are dated to 1942 and were based in Kinshasa. The ensemble Américain, founded in 1945 and led by Pierre Disu, emerged within a context shaped by the temporary presence of American military personnel stationed at Ndolo airfield during World War II.[29] These troops, monitoring Soviet submarine activity, entertained local audiences with New Orleans-style jazz. In both Américain and Odéon Kinois, proficiency in musical notation (solfège) was a prerequisite for membership.[29] According to Antoine Wendo, the earliest Congolese ensemble predating the influence of the Coastmen and the Excelsior Orchestra was that of Antoine Kasongo Kitenge, a clarinetist and later saxophonist originally from Maniema. Kasongo received musical training in the brass band of Sainte-Cécile School in Kintambo, later joined by Jean Lopongo. He went on to establish his own jazz orchestra, which performed at public dances in Parc de Bock (now Kinshasa Botanical Garden). Despite assertions by musicologist Clément Ossinondé, Kasongo's orchestra was distinct from Odéon Kinois.[29]

The Martinique Orchestra, directed by Rufin Mutinga—described as "deputy assistant to the first burgomaster"—bears a name with debated origins. According to Matondo, it likely derived its name from the cultural presence of Martinican soldiers stationed in Brazzaville. These soldiers, performing for recreation, contributed to the spread of the biguine rhythm, commonly referred to locally as "martiniquais".[29] This rhythm, also popularized by the Américain group, shared stylistic similarities with the musical approach of Odéon Kinois. During this period, many Congolese orchestras incorporated the biguine rhythm into their repertoire, adapting it to local musical idioms.[29] Antoine Kasongo began releasing music through the Olympia label in 1947, before signing with Ngoma in 1949. His collaboration with guitarist Zacharie Elenga, known as "Jimmy à la Hawaïenne" (Jimmy the Hawaiian), resulted in several influential recordings, including "Libala liboso se sukali" ("Marriage is sweet at first"), "Baloba balemba" ("We don't care about their gossip"), "Naboyaki kobina" ("I refused to dance"), "Se na mboka" ("It's in the village"), "Sebene", "Nzungu ya sika" ("New pot" or metaphorically, "new woman"), among others.[29] Notably, vocalists Jeanne Ninin and Caroline Mpia contributed significantly to these recordings.[29] The sebene, an instrumental bridge used to accentuate guitar improvisation, emerged prominently during this period and is largely attributed to Kasongo's innovation.[35][36] Contrary to Ossinondé's interpretation, Harmonie Kinoise and Odéon Kinois were not necessarily the same ensemble.[29] Nyimi Nzonga refers to Kasongo's group simply as "Antoine Kasongo and his orchestra" under the Ngoma label. He describes Kasongo as a virtuoso of solfège who trained initially in the brass band of the Marist Brothers' School in Kisangani and who briefly performed with Américain, a rival group composed of alumni from the Colonial School of Boma.[29]

By the 1950s, several local record labels, including CEFA (Compagnie d'Énregistrements Folkloriques Africains), Ngoma, Loningisa, Esengo, and Opika, began releasing 78 rpm records, which thus facilitated the genre's spread.[37][38][39][40] Belgian producer Bill Alexandre, working with CEFA, introduced electric guitars to local musicians.[37] During this period, the Kinshasa population grew exponentially, rising from 49,972 in 1940 to over 200,000 by 1950. This expansion brought increased ethnic and racial diversity, and established Kinshasa as a central hub of cultural and economic activity in the Belgian Congo.[29] The city's urban growth was mirrored by the proliferation of leisure spaces, particularly bars and nightclubs, which became prominent sites of social interaction, musical performance, and entertainment for both migrant laborers and urban residents.[29] These establishments played a dual role: while serving the colonial administration's agenda for pacification and social control (often referred to as the "Pax Belga"), they simultaneously provided the African population with venues for leisure, self-expression, and community-building.[29] Bars were described as centers of style, sociability, and emerging cultural values. They were venues where aesthetic sensibilities, financial status, and modern identities were publicly displayed.[29] Of the more than one hundred bars operating in Kinshasa by the mid-century, approximately twenty held official authorization to host dancing. Prominent among these were the O.K. Bar, Macauley, Kongo Bar, Siluvangi, Quist, Zeka Bar, Amouzou, Air France, and the Home des Mulâtres.[29] These establishments were referred to as "the pride and heart of urban life", epitomizing what was perceived as the pinnacle of the urban culture generated through colonial capitalist contact.[29] Some of these bars were owned or managed by Coastmen, while others, such as the Home des Mulâtres, were marked by racial segregation, serving only the métis population. This latter venue in particular symbolized the persistence of colonial racial hierarchies in spaces that might otherwise have fostered social integration.[29]

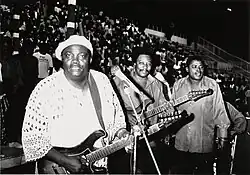

In 1953, the Congolese music scene began to differentiate itself with the formation of African Jazz (led by Joseph "Le Grand Kallé" Kabasele), the first full-time orchestra dedicated to recording and performance, and the emergence of fifteen-year-old guitarist Franco Luambo.[41][42][43] Both would become among the earliest luminaries of Congolese music.[41][42][43]

1950–70

Return to maringa and integration of traditional elements

By the early 1960s, many imported dance and music styles had fallen out of favor, replaced by guitar-driven forms rooted in traditional Congolese sources. Ethnomusicologist Kazadi wa Mukuna observed that as the novelty of Latin American influences waned, musicians returned to maringa, which was easily adapted to modern instrumentation. This approach re-integrated traditional rhythms and dances into rumba's structure without compromising local aesthetic principles.[34] Modern instruments expanded the harmonic and tonal range, with the guitar supplanting both indigenous melodic instruments—such as the likembe and madimba—and certain European imports like the violin and accordion. During this transitional period, Congolese rumba—often still called maringa—proved highly adaptable to indigenous rhythmic frameworks.[34] Its standard structure evolved into a multi-section format: an instrumental prelude, the principal verse (sometimes abstract in delivery), an instrumental interlude, a reprise of the verse with a modified cadence leading to the refrain (frequently a call-and-response between the lead vocalist and chorus), the sebene improvisation, and a coda derived from the refrain.[34] This framework permitted extensive improvisation, encouraging rhythmic and melodic innovation and giving rise to numerous substyles. Among the most notable were soukous (1966), kiri-kiri (1969), cavacha (1972), mokonyonyon (1977), engoss and its variant zekete-zekete (1977–1987), kwassa kwassa, (1986), madiaba (1988), mayebo (1990), mayeno (1991), and sundama and kintekuna (1992).[34] These developments were strongly tied to ethnic traditions, as many new dances incorporated movements from specific communities. For example, Papa Wemba's mokonyonyon (1977) drew from the Tetela people's dances, while Lita Bembo's Ekonda saccade (1972) reflected Mongo heritage. The sundama, popularized by Swede-Swede, also originated from Mongo traditions.[34] The kwasa-kwasa, introduced in 1986 by Empire Bakuba, echoed a Kongo social dance, and the mayeno style of TPOK Jazz was derived from Bantandu traditions of Kongo Central.[34] Ultimately, the evolution of Congolese rumba adhered to indigenous aesthetic norms, which affirmed Kazadi wa Mukuna's view that urban Congolese music was fundamentally rooted in maringa rather than in borrowed Latin forms.[34] The Latin American rumba and other foreign forms introduced in the 1940s primarily served as training tools for mastering new instruments and orchestration. Once these skills were acquired, Latin forms were abandoned due to their limited adaptability to Congolese traditions.[34] However, the term "rumba" persisted largely due to the commercial strategies of the recording industry, even as the music itself had become an entirely localized cultural expression.[34]

Big bands

During the 1960 Round Table Conference in Brussels, convened to determine the political future of the Belgian Congo, Congolese nationalist Thomas Kanza arranged for musicians to participate in diplomatic and social functions.[44] On 27 January 1960, Joseph Kabasele (known as "Le Grand Kallé") and his band, African Jazz, became the first Congolese musical group and rumba band to perform in Brussels.[45][46][47] That day, they debuted the Congolese rumba song "Indépendance Cha Cha" at the Hôtel Plaza to mark the formal recognition of the Congo's forthcoming independence, which would be proclaimed on 30 June 1960.[48][49][50] Sung in Lingala, the composition became an anthem for independence movements across Francophone Africa and was widely performed at public celebrations and gatherings.[51][52]

Throughout the 1960s, both African Jazz and TPOK Jazz maintained prominence in the Congolese music scene, with TPOK Jazz under Franco Luambo Makiadi ultimately dominating for two decades.[41][43][53][54] African Jazz experienced significant internal fractures, beginning in 1963 when its guitarist Nicolas Kasanda, known as Docteur Nico, and his brother Charles Déchaud Mwamba departed following financial disputes.[55][56] Although temporarily reconciled in 1961, tensions persisted.[56] In 1963, Docteur Nico and vocalist Tabu Ley Rochereau left permanently to form African Fiesta.[57][58] Their collaboration dissolved in 1965, leading Tabu Ley to rebrand the band as Orchestre African Fiesta 1966, later Orchestre African Fiesta National Le Peuple, and eventually Orchestre Afrisa International, alongside the creation of his own record label, Flash, which was sometimes called "Editions Flash", "Flash Rochereau Chante", or "Flash Edition Express Rochereau Chante".[59][60][61] Docteur Nico founded African Fiesta Sukisa.[57][58]

Docteur Nico was instrumental in defining the role of the electric guitar in African popular music, pioneering the integration of the mi-solo guitar into Congolese rumba and influencing the development of soukous.[62] Unlike the two-guitar structure common in Western genres, Congolese dance music employed three guitars: rhythm, mi-solo (half-solo), and lead. The mi-solo often carried syncopated ostinatos, or guajeos, complementing the harmonic progression and freeing the lead guitar to perform elaborate melodic lines.[62] Dr. Nico's style, characterized by fluid arpeggios, double-stops, rhythmic punctuations, and the use of tremolo and reverb, contrasted with Franco's more traditionalist approach.[62][63][64][65] His work earned him the epithet L'Éternel Docteur Nico ("the Eternal Doctor Nico"), and his reputation extended internationally, and American guitarist Jimi Hendrix expressed a desire to meet him during a Paris tour after hearing of his technical mastery.[62]

Despite the prestige of Orchestre Afrisa International, it could not match the sustained influence of TPOK Jazz. Rivalries between bands often included attempts to recruit each other's musicians, sometimes leading to public exchanges, such as Franco's satirical open letter in L'Étoile du Congo. Papa Noël Nedule, who trained notable figures including Pépé Kallé and Madilu System, also faced the loss of musicians to rival bands.[56] Nevertheless, these orchestras served as formative institutions for some of the most influential Congolese artists, including Franco Luambo, Sam Mangwana, Vicky Longomba, Ndombe Opetum, Dizzy Madjeku, and Verckys Kiamuangana Mateta.[41][43][66] Sam Mangwana, in particular, maintained a strong following across various bands, from Vox Africa and Festival des Marquisards to Afrisa, TPOK Jazz, and later his own African All Stars.[67][68][69] Other significant orchestras of the era included Orchestre Conga-Jazz and Orchestre Cobantou, the latter founded by Paul Ebengo Dewayon.[70] Meanwhile, Mose Se Sengo of TPOK Jazz extended the reach of Congolese rumba to East Africa, particularly Kenya, after relocating there in 1974 with his band Somo Somo.[71][72][73][74] Beyond Central Africa, Congolese rumba proliferated through the rest of Africa.[75][76][77]

During the same era, students at Lycée Prince de Liège in Gombe, Kinshasa, developed a fascination with American rock and funk, especially after James Brown visited Kinshasa in 1974. From this environment emerged Los Nickelos and Thu Zahina.[78][79][80][81][82] Los Nickelos later moved to Brussels, while Thu Zahina, though short-lived, achieved legendary status for their throbbing performances characterized by frenetic, funk-infused drumming during the sebene and an often psychedelic edge.[78]

Zaiko and post Zaiko (c. 1970–90)

| Part of a series on the |

| Culture of the Democratic Republic of the Congo |

|---|

|

| History |

| People |

| Languages |

| Cuisine |

| Religion |

| Sport |

Stukas and Zaïko Langa Langa were the two most influential bands to emerge from this era,[83][84][85][86] with the latter serving as a formative platform for prominent musicians such as Félix Manuaku Waku, Bozi Boziana, Evoloko Jocker, and Papa Wemba.[87][88][89] During the early 1970s, a smoother and more melodious pop style was popularized by ensembles including Orchestre Bella Bella, Orchestre Shama Shama, and Lipua Lipua, while Verckys Kiamuangana Mateta promoted a raw, garage-like sound that fostered the careers of Pépé Kallé and Kanda Bongo Man.[86][90][91]

This period coincided with significant political and cultural transformations under President Mobutu Sese Seko, and in 1971, against the backdrop of relative economic stability, growing international recognition, and the suppression of political opposition, he initiated the process of Zaireanisation (also known as authenticité).[92] Although Zaire faced an intensifying economic crisis due to inadequate investment in infrastructure, central Kinshasa was presented as a showcase of prosperity to the international community. These efforts reflected Mobutu's emphasis on projecting an image of modernity through symbolic displays of power.[92] Before Mobutism was codified as the official state ideology, authenticité functioned as a cultural program designed to forge a distinct national identity. Citizens were required to adopt African names, wear attire imbued with "revolutionary" symbolism, and address one another as citoyen rather than monsieur.[92] Popular music played a central role in this project, as Mobutu reorganized the industry to align with authenticité by transferring foreign-owned recording and distribution companies to Zairean nationals, appointing Franco Luambo as his cultural envoy, and financing artists through a state-run recording agency.[92] In return, popular music was harnessed to reinforce the regime's image.[92] By the 1980s, musicians who had emerged from Zaïko Langa Langa dominated Kinshasa's cultural scene, founding influential bands such as Choc Stars and Viva La Musica, the latter under Papa Wemba's leadership.[86][87]

Internationalization of soukous and the rise of ndombolo

During the 1980s, mounting sociopolitical upheaval in Zaire prompted many musicians to relocate abroad. Tanzania, Kenya, Uganda, and Colombia served as temporary refuges, while Paris, Brussels, and London developed into major centers for Congolese music.[93][94][95][96][97] Paris, in particular, became a hub for soukous, where Congolese musicians engaged with European and Caribbean influences, synthesizers, and modern production techniques.[98] Soukous in this period garnered a wide global following, with leading figures such as Papa Wemba, Pépé Kallé, Kanda Bongo Man, and Rigo Star achieving acclaim across Europe, Africa, and the Caribbean.[99][100][101] Papa Wemba also became closely associated with the La Sape movement, a cultural phenomenon defined by flamboyant displays of luxury fashion.[102][103][104][105] Meanwhile, Kinshasa continued to produce notable musicians such as Bimi Ombale and Dindo Yogo.[106][107][108] The diversification of genres included the rise of madiaba and the popularization of Tshala Mwana's mutuashi, rooted in Luba tradition.[109][110][111][112] In 1985, Franco and TPOK Jazz released Mario, an album steeped in Congolese rumba; its title track became an immediate hit, selling over 200,000 copies in Zaire and earning gold certification.[113] Zaïko Langa Langa also cemented its international reputation by appearing on French national television (TF1) in 1987 and securing second place in the Référendum RFI Canal Tropical, behind the Antillean band Kassav'.[114]

From the late 1980s onward, successive generations of musicians continued to redefine Congolese popular music. Among Viva La Musica's protégés, Koffi Olomide emerged as the most influential figure of the early 1990s.[115][116] His main rivals were J.B. Mpiana and Werrason, both veterans of Wenge Musica, a band that played a pivotal role in developing ndombolo.[117] Characterized by rapid guitar lines, synthesizer-driven arrangements, energetic percussion, and the interplay of atalaku chants with melodic vocals,[118][119][120] ndombolo dominated Congolese music throughout the 1990s and 2000s.[121][122][123] Even Koffi's later repertoire increasingly centered on ndombolo compositions.[124][125]

Hip-hop

Kinshasa emerged as a hub for Congolese hip-hop through a complex convergence of cultural shifts, political change, and youthful determination. While the city in the late 1980s and 1990s was largely dominated by "musique typique"—a vibrant tradition led by prominent figures such as Koffi Olomidé, Werrason, and JB Mpiana—a new generation of artists began carving space for hip hop as early as the 1990s.[126] The roots of the Congolese hip-hop movement can be traced to the twilight years of Mobutu Sese Seko's regime when political instability and growing disillusionment among youth created fertile ground for alternative cultural expression. Affluent teenagers in residential neighborhoods, exposed to American and French rap through satellite television and tapes sent from relatives abroad, began emulating this genre, performing at student parties and school dances.[126] The fall of Mobutu in 1997, during the First Congo War, marked a pivotal shift: the liberalization of the media landscape allowed the proliferation of private radio and television stations, making unprecedented exposure for local rap music to be aired alongside dominant Congolese genres.[126]

Between 1997 and 2001, pioneering Congolese rap groups based in Kinshasa, including Bawuta-Kin, PNB (Pensée Nègre Brute), Section Bantoue, and Smoke emerged, self-producing their music with scant financial resources. Operating on modest budgets, they recorded in home studios, pooled money to shoot music videos, and paid television hosts for ephemeral airplay slots.[126] These early artists encountered resistance in a musical culture that had long been rooted in danceability, rhythmic energy, and escapist lyricism. In contrast, hip-hop's proclivity for incisive social commentary rendered its practitioners as iconoclasts—derisively labeled empêcheurs d'ambiancer en rond, or killjoys—within a community that preferred music that encouraged euphoric enjoyment.[126] Despite scarce commercial support, especially after local music producers fled during the looting of the early 1990s, Kinshasa's rap scene persisted. Artists turned to public venues like La Halle de la Gombe to perform in professional conditions.[126] Meanwhile, rap spread from the elite neighborhoods into working-class areas such as Ndjili, the Yolo quartier of Kalamu commune, and Kabambaré Territory in Maniema Province, with youth incorporating Lingala, French, Kikongo, Swahili, and other local languages into their lyrics.[126] Some acts, like Bawuta-Kin and PNB, incorporated samples from Congolese music legends such as Franco Luambo, Koffi Olomidé, and Tshala Muana, creating a distinctive local flavor that helped bridge generational and cultural divides.[126] The scene's growing legitimacy was underscored by a landmark moment in December 2003, when approximately 60,000 people gathered at the Stade des Martyrs for a major hip-hop concert. Although often marginalized and lacking financial backing, Kinshasa's hip-hop artists succeeded in establishing a vibrant subculture.[126] One of the movement's most influential figures is Lexxus Legal, a co-founding member of PNB. Known for his politically engaged lyrics, Lexxus Legal became a symbol of Congolese hip-hop activism.[129][130][131][132] He earned national and international recognition, receiving accolades such as the African Renaissance Hip Hop Award (Senegal, 2010) and the Ndule Award (2009).[129][130][133] He is widely regarded as the "icon of Congolese hip hop" and a prominent voice in African rap.[129][134]

Other artists followed with varying stylistic approaches. Goma-born rapper Innoss'B gained continental recognition with his 2017 hit "Ozo Beta Mabe",[135][136][137][138] and became the first Congolese musician to surpass 100 million YouTube views with his "Yo Pe" remix featuring Tanzanian singer Diamond Platnumz.[139][140][141] Kinshasa native Gaz Fabilouss achieved similar success with his 2018 EP Jeune courageux, which produced popular tracks like "Aye" (featuring Koffi Olomidé), "Salaire", and "Love Story".[142] Rapper Alesh, born in Kisangani, is noted for his sharp political commentary and humorous portrayal of Congolese life. His 2018 single "Biloko ya boye", released in the lead-up to national elections, urged voters to hold corrupt politicians accountable.[143] His lyrics frequently explore themes such as governance failures, poor living conditions, and social inequality.[143]

Similarly, the duo MPR (Musique Populaire de la Révolution), composed of Zozo Machine and Yuma, embraces a nostalgic aesthetic drawn from Mobutu-era symbolism.[143] Their 2019 breakout track "Dollars" catalyzed widespread recognition,[143] followed in 2020 by their inclusion in the rap collective Cité Zaïre, whose freestyle "Éternel Courageux" exhorted Congolese youth toward self-determination and industriousness.[144] MPR's 2021 mixtape Première leçon, featuring tracks such as "Nini to sali té", garnered acclaim for its critique of post-independence governance.[145][146][147] The song opens with a direct appeal—"Father, nini to sali té"—and traces the struggles of a Congolese youth who, despite completing his education and turning to faith, remains unemployed and destitute. The music video concludes with a tragic climax: the young man's mother dies due to lack of access to medical care, symbolizing the despair many young Congolese experience.[146][148] The video was banned nationwide by the National Commission for the Censorship of Songs and Entertainment (Commission nationale de censure des chansons et des spectacles; CNCCS) for violating procedural regulations, including failure to seek prior approval—a common tactic used to restrict politically sensitive content.[146][149][150] In the same vein, Kinshasa-based rapper Bob Elvis also rose to fame through politically conscious compositions that confront institutional hypocrisy.[151][152] His track "Lettre à Ya Tshitshi" criticizes the distribution of luxury vehicles to national deputies, juxtaposing this extravagance with ongoing social neglect. The accompanying music video depicts the artist standing before a coffin adorned with the image of Étienne Tshisekedi, symbolically addressing the deceased opposition leader and father of President Félix Tshisekedi.[146][149] Through this visual and lyrical homage, Bob Elvis questions the sincerity of the ruling party's slogan, "Le peuple d'abord" ("The People First"), and highlights enduring issues such as lack of clean water, political deadlock, the M23 conflict in the east, and widespread unemployment. Like MPR, Bob Elvis also faced state censorship, with six of his videos—including "Lettre à Ya Tshitshi"—being banned.[146][149]

Female representation in the Congolese hip-hop scene remains limited, but Sista Becky has emerged as a trailblazer. Releasing her debut single "Mr le Rap" in 2017, she followed with tracks like "Flip Flop", "Notorious Spirit", and "Emotions", establishing herself as the leading female voice in a male-dominated space.[143] In 2023, Kolwezi-born RJ Kanierra experienced rapid success with his single "Tia", which amassed over two million YouTube views in just two weeks.[153][154] The track topped charts on various platforms, including Boomplay and Shazam,[155][156] and inspired a viral dance challenge embraced by celebrities such as boxer Martin Bakole and comedian Herman Amisi.[157][158][159] Mbote.cd, a leading Congolese entertainment site, named Tia "Song of the Year".[160] Other noteworthy contributors to the genre include Marshall Dixon, NMB La Panthère, Lyke Mike, Herléo Muntu, K-Melia, Negue Fly Nsau, Celeo Scram, and Spilulu.[161]

Politics

Early political engagement (1965–1970)

The intersection of politics and popular music has been a defining feature of the country's cultural history, particularly since the mid-20th century. Congolese musicians have often acted as both chroniclers and promoters of political developments. The military coup of 24 November 1965, which brought Mobutu Sese Seko to power, occurred at a time when the Congolese political class was still in its formative stage.[162] In the aftermath, the public seeking stability and peace generally welcomed the new regime, which had promised to return power to civilian authorities within five years, a pledge that was never fulfilled. In the first decade of Mobutu's rule, music became a medium through which the regime's political and socio-economic objectives were communicated.[162] Themes in popular songs included nationalism, pan-Africanism, political programs, and notable political events. Early examples include Franco Luambo and TPOK Jazz's "Contentieux Belgo-Congolais enterré" ("Belgian-Congolese Dispute Buried", 1967) and Jean Munsi Kwamy with Orchestre Révolution's "Ndimbala ya Zaïre" ("Explanation of the Zaïre Currency", 1967).[162] Tabu Ley Rochereau contributed several works, including "Cinq ans" ("Five Years", 1965) with African Fiesta, "Objectif 80" (1966) with African Fiesta 66, and "Révolution comparaison" (1968) with Orchestre Afrisa International. Other notable songs from the era include Lasse and Orchestre Los Angel's "Retroussons les manches" ("Let's Roll Up Our Sleeves', 1966) and Jeannot Bombenga's 1967 "Mbula ya sacrifices" ("1967 Year of Sacrifices", 1967).[162]

While this alignment with state narratives afforded musicians increased visibility, it also drew criticism from the public and the national press, who accused certain artists of partisan opportunism. Nevertheless, Congolese popular music established a distinctive political voice, portraying national leaders to the public, celebrating their achievements, and promoting state policies.[162] Notable examples included Joseph Mwena and African Fiesta National's "Lumumba libérateur" (1967), Bikasi Mandeko and Orchestre Saka Saka's "Mobutu médiateur" (1968), Tabu Ley Rochereau and Afrisa International's "Martin Luther King" (1968), and Tabu Ley Rochereau and L'Orchestre African Fiesta National Le Peuple's "Kashama Nkoy" (1969).[162]

Political figures, the cult of personality, political animation, and propaganda

Throughout the 1970s, musical references to political figures became increasingly tied to electoral campaigns or commemorations of state events. Notable examples from this period include Franco and TPOK Jazz's "Mwaku elombe ya Kwango" (1970), "Président Eyadema" (1975), "Votez Litho Moboti au Bureau Politique" (1977), and "Votez Bomboko au Bureau Politique" (1977). By the latter part of the decade, these references largely concentrated on the person of the President.[162]

Following the establishment of the Popular Movement of the Revolution (Mouvement Populaire de la Révolution, MPR) in 1967, music became an instrument for reinforcing the one-party state's ideology and for mythologizing Mobutu. Nationalist ideals gradually ceded to political opportunism and, in some cases, uncritical glorification.[162] Mobutu was extolled through grandiose epithets such as "father", "guide", "messenger of God", "leopard", "sun", and "prophet".[162] Songs emblematic of this period included Bombenga and Orchestre Vox Africa's "C.V.R." ("Corps des Volontaires de la République", 1966), Joseph "Mujos" Mulamba and Orchestre Révolution's "M.P.R." (1967), Paul Ebengo Dewayon and Orchestre Cobantou's "M.P.R." (1967), Jojo and Orchestre Dombes' "M.P.R. ekobenga banso" ("M.P.R. Calls Everyone", 1967), Sam Mangwana and Orchestre Festival des Maquisards' "Congo ya M.P.R." ("Congo Goes with M.P.R.", 1967), Franco and TPOK Jazz's "Votez vert" ("Vote for You", 1970), and Franco and TPOK Jazz's "Candidat na biso Mobutu" ("Mobutu is My Candidate", 1984).[162]

In 1973, the regime institutionalized the concept of "political animation songs", blending popular, folk, and modern dance styles into compositions that celebrated the President and promoted the tenets of Mobutism. The First National Political and Cultural Festival (Premier Festival National Politique et Culturel) brought together political animation groups from all provinces.[162] This initiative led to the creation of the Ministry of Mobilization, Propaganda, and Political Animation (Mobilisation, Propagande et Animation Politique; MOPAP), institutionalizing musical propaganda. Political animation eventually permeated even religious music, exemplified by the work of Father Imana Botumbi.[162] Despite state control, some musicians returned to the traditional role of the artist: to educate, raise moral awareness, and, at times, voice dissent. When criticism was too overt, the state censorship apparatus responded with severity. For example, Franco's alleged "Cravate nationale" ("National Tie"), reportedly inspired by the 1966 execution of the "Pentecost martyrs", was never released and resulted in state security intervention.[162] To evade censorship, musicians often employed allegory, metaphor, and riddles, allowing audiences to decode political messages through "popular rumor".[162] Works exemplifying this approach include Tabu Ley Rochereau and African Fiesta National Le Peuple's "Mokolo Nakokufa" (1966), Roy Innocent and Orchestre Cobantou's "Nyama ya Zamba" (1968), Tabu Ley Rochereau and African Fiesta National Le Peuple's "Kashama Nkoy" (1969), Franco and TPOK Jazz's "Lettre à M. D.G." (1987), and Franco and TPOK Jazz's "Tailleur" (1987).[162]

The democratic transition (24 April 1990–17 May 1997)

The democratic transition in Zaire was formally initiated on 24 April 1990, marking the official end of the one-party state. The shift from a single-party system to what was often described as "excessive multipartyism", combined with a partial relaxation of the state's stringent censorship on free expression, produced a proliferation of political leaders, reminiscent of the First Republic, and a multitude of party founder-presidents.[162] This rapid political diversification, however, generated widespread confusion among the populace, politicians, and musicians. Political developments occurred at a relentless pace, involving a series of round tables, the Sovereign National Conference (Conférence nationale souveraine), and multiple agreements—most of which were violated shortly after their signing.[162] Musicians often struggled to process these events or to respond in a manner with enduring artistic and political impact. Questions emerged over what subjects to address, and for whom the messages should be intended, with the risk of public ridicule looming over overtly political works.[162] An example of this was Simaro Lutumba and TPOK Jazz's "Banque Centrale" (1994), intended to promote public understanding of monetary reform and encourage civic responsibility. Released on 1 January 1994, the song was rendered politically obsolete within days, as the government acknowledged the reform's failure (a fact confirmed by the President himself in a speech on 4 January).[162]

During the Sovereign National Conference, specially commissioned songs were broadcast on television and radio as introductory themes to news segments. However, these works were short-lived, quickly replaced as political circumstances shifted. The song "La réconciliation" (1992) by Madilu System and Deneewade became emblematic of the "catastrophic" conclusion of the conference.[162] The final decade of the Second Republic offered little social relief to Congolese citizens, and musicians, still reeling from two decades of creative repression, often appeared disengaged from political commentary.[162] Many artists had gone into exile and their contribution during the democratization process was "negative across the board". Unlike earlier generations (represented by Adou Elenga, Le Grand Kallé, and Paul Lomami-Tshibamba) whose works had seized political milestones, the democratization period left little in the way of a musical record for posterity.[162] One notable exception was Tabu Ley Rochereau's "Le Glas a sonné" (1993), produced in exile, which addressed the political situation directly. Yet such cases were rare, and many established artists remained silent, whether out of fear of reprisals, disillusionment, or lack of inspiration.[162]

With the dismantling of the one-party propaganda apparatus, political songs disappeared from the airwaves, and the slogans and melodies once imposed on the public were quickly forgotten. In their place, religious choirs flourished. Religious music, which had entered the realm of political animation under Father Imana Botumbi, reclaimed its spiritual mission during the democratic transition.[162] Figures such as Father Makamba Ma Mazinga produced widely circulated works, including "Popopo" (1993), "Non violence", and "Kanda Mopaya" ("Anger is fleeting"), which struck a chord throughout Kinshasa and beyond, aiming to promote moral and social consciousness by commemorating the looting and the martyrs of the Christian marches on 2 and 16 February 1992, events that had largely faded from public memory.[162] Among the most memorable religious compositions of the era was "Ata Ndele" (1993) by the group Bana Mbila, which, in the face of political selfishness and public suffering, expressed a message of hope, saying that there is hope in tomorrow and that one day everything will change and misery will come to an end.[162] The arrival of the Alliance of Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Congo-Zaire (AFDL) and the fall of Mobutu on 17 May 1997 ushered in a new political phase, during which musicians appeared to regain their voice, inaugurating the post-Mobutu period with works such as Tshala Muana's song celebrating liberation and Tabu Ley's piece warning President Laurent-Désiré Kabila of the challenges ahead and advising on how to avoid them. Both compositions were adopted as theme music on radio and television.[162] A significant innovation during this phase was the collaborative approach among musicians, who increasingly focused on patriotic themes under the maxim "unity is strength". This collective nature yielded works such as "Mwana Pwo" (supporting monetary reform) and the jointly composed "Tokufa mpo na ekolo" (1998), intended to revive patriotism and reinforce the sense of national unity.[163]

Religious music

Origins and early developments

Religious music embodies an intricate balance of the sacred and the profane, firmly anchored in the cultural, social, and spiritual identity of the country. Historically confined to church settings, it gradually expanded into public life and became a significant force in shaping religious practice and popular culture. Its evolution mirrors the evolution of Congolese society, where spirituality permeates artistic expression and secular traditions borrow freely from the sacred.[164]

The earliest manifestations of Congolese religious music emerged in church choirs and brass bands associated with Catholic, Protestant, Kimbanguist, and Salvation Army congregations, which served as training grounds for successive generations of performers.[164] In its initial phase, sacred music was predominantly restricted to liturgical contexts, with hymns of praise performed during worship services or within mourning households, where they conveyed solemnity and consolation.[164] During the colonial period, significant institutional efforts shaped the early history of Congolese liturgical song. In the 1940s, Benedictine father Dom Anschaire Lamoral founded the choir Petits Chanteurs de la Croix de Cuivre (Little Singers of the Copper Cross) in Katanga, mentoring Joseph Kiwele, who composed the "Missa Katanga", notable for its integration of drums and traditional instruments into Catholic worship.[164] Similarly, Father Joseph Malula (later elevated to Cardinal) championed the incorporation of local musical forms into Catholic liturgy, culminating in the creation of the Zairean Rite in 1973. This liturgical reform codified the integration of local rhythms and instruments into Roman Catholic rituals.[164]

The Salvation Army likewise contributed significantly, particularly through its orchestra Les Vagabonds du Ciel and choir Les Amis du Ciel, which were instrumental in nurturing Christian musicians in Middle Congo.[164] Across the Congo River in Brazzaville, Father Charles Lacompte founded the Petits Chanteurs de la Croix d'Ébène (Little Singers of the Ebony Cross) in 1949, later renamed the Chorale des Piroguiers (Boatmen's Choir). This ensemble delivered a landmark performance of "La Messe des Piroguiers" by Eliane Barrat Peppert—broadcast live on Radio-Brazzaville—marking a pivotal moment when African percussive instruments, specifically the drum of the Banda boatmen of Ubangi-Shari (today's Central African Republic), were formally introduced into liturgical music.[164] The performance took place during the consecration of the Basilica of Sainte-Anne by Bishop Paul Biéchy, attended by high-ranking ecclesiastical figures and colonial administrators. Additional choirs such as the Chœur Saint François d'Assise du Plateau in Brazzaville's Bacongo arrondissement emerged during the 1940s.[164]

Sacred–secular overlap and the rise of revivalist Christian music

The boundary between religious and secular music in the DRC has historically been porous. Many leading figures in Congolese popular music—such as Le Grand Kallé, Célestin "Célio" Kouka, Vicky Longomba, Sammy Trompette, Verckys Kiamuangana Mateta, José Dilu Dilumona, Jossart N'Yoka Longo, Pépé Kallé, Papa Wemba, D. V. Moanda, among others—began as choristers or cantors in church choirs before transitioning to secular performance.[164] Likewise, secular songs often contained spiritual themes. A notable example is François Bosele's "Liwa Liponi Tata" (released in the early 1950s), which, although secular in intent, gained widespread acceptance in religious settings due to its evocative spiritual imagery.[164][165] Throughout the 1960s and 1970s, this duality persisted. Figures such as Archbishop Barthélemy Batantu ("Nkundi"), Ntesa Dalienst ("Tokosenga Na Nzambe", 1971), and Verckys ("Nakomitunaka", 1972) produced works that invoked divine themes.[164] The 1970s also saw the emergence of groups such as Les Perles (later Palata), who drew inspiration from American gospel traditions, and orchestras like Le Peuple, which performed religiously inspired works in secular styles.[164]

From the 1980s onward, the growth of revivalist churches on both banks of the Congo River led to the widespread adoption of Christian music as a standalone genre. What began as congregational choirs evolved into full-fledged orchestras, structurally modeled on secular bands but dedicated to spiritual themes.[164] This movement produced a generation of musicians who identified themselves as "Christian musicians" or "musician-Christians". Unlike traditional church-based groups, they were affiliated with revivalist congregations rather than traditional denominational affiliations.[164] Rather than rejecting secular aesthetics, these groups retained the danceable rhythms, melodic contours, and harmonic textures characteristic of Congolese popular music, thus eroding clear-cut distinctions between religious and secular domains.[164] The genre spread rapidly and became embedded in Congolese social life, providing spiritual expression and entertainment. Notable figures in Kinshasa include Charles Mombaya, Brother Kabatshi, Brother Mente, Paul Balenza, the Couple Buloba, Dénis Ngonde, Kool Matopé, Runo Mvumbi, Kangumba, Brother Patrice Ngoy Musoko, Alain Moloto, Lifoko du Ciel, Maninga, Matou Samuel, Blaise Sakila, Feza Shamamba, Marie Misamu, and the Cœur La Grâce choir, among others.[164] In Brazzaville, notable names include the Tanga Ni Tanga choir, Batangouna Sébastien, Christian Mahoukou, Moise Baniakina, Loudi Berthe, Tukindisa Nkembo, Sita Philippe, Sainte Odile Choir, Zola Choir, Les Colombes, and more.[164] Their work popularized Congolese Christian music across Central Africa and beyond, aided by the proliferation of cassettes and broadcasts by publishers and producers who recognized the growing market for religious recordings.[164]

Conversion of secular musicians, media spread, and modern challenges

A significant feature of Congolese religious music has been the conversion of secular performers to sacred expression, a trend that gained visibility during the 1990s with artists such as Antoinette Etisomba Lokindji, Mopéro Wa Maloba (formerly of Orchestre Shama Shama), Kiese Diambu (formerly of Les Grands Maquisards, Afrisa International, and TPOK Jazz), Djonita Abanita, X-Or Zobena (formerly of Choc Stars), Debaba (formerly of Viva La Musica and Choc Stars), Carlyto Lassa (formerly of TPOK Jazz and Choc Stars), André Bimi Ombale (formerly of Zaïko Langa Langa, Zaïko Familia Dei, and Basilique Loningisa), Feza Shamamba, Michel Ndouniama (formerly of Bilenge Sakana), Jolie Detta, Charles Tchikou, and others.[164] These musicians released Christian albums and integrated biblical themes into their repertoires, often surprising fans accustomed to their secular hits.[164]

Over time, Congolese Christian music developed its own distribution networks, beginning with the establishment of Radio Sango Malamu as the first thematic station dedicated to religious music, which paved the way for others, including Radio Télé Message de Vie, Radio Télé Kintwadi, Radio Elikya, Radio Télé Puissance, Radio Télévision Armée de l'Éternel (RTAE), Amen TV, Canal le Chemin, La Vérité et la Vie, and many more.[164]

In contemporary times, Congolese Christian music constitutes a genuine cultural phenomenon that rivals secular music in popularity, borrowing many of its stylistic features, including atalaku vocal interjections, intricate guitar solos, and choreographed dance routines.[164] This stylistic convergence, however, has provoked debate, with critics arguing that the heavy reliance on secular aesthetics risks diluting the spiritual depth of Christian music, transforming it into another branch of variety entertainment.[164] Nevertheless, its ability to uplift believers and provide spiritual reassurance preserves its relevance within Congolese society.[164]

References

- ^ Haugerud, Angelique; Stone, Margaret Priscilla; Little, Peter D., eds. (2000). Commodities and Globalization: Anthropological Perspectives. Lanham, Maryland, United States: Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 34–49.

- ^ "Beneath the rhythm, Congolese rumba is a link to the past". The Economist. 22 January 2022. ISSN 0013-0613. Retrieved 22 August 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Enyimo, Martin (6 August 2005). "Congo-Kinshasa: Instruments et cris traditionnels dans le folklore congolais" [Congo-Kinshasa: Traditional Instruments and Cries in Congolese Folklore]. Le Potentiel (in French). Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of the Congo. Retrieved 29 July 2025.

- ^ Ambrose, Robert (19 October 2000). "Congo-Kinshasa: Likembé Géant Making Music That is the Essense of Classic Rumba". allAfrica. Retrieved 29 July 2025.

- ^ Okamba, Emmanuel (30 March 2022). "La "Rumba", un humanisme musical en partage" (in French). Lyon, France: HAL. p. 5. Retrieved 15 December 2023.

- ^ Martin, Phyllis (8 August 2002). Leisure and Society in Colonial Brazzaville. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. pp. 131–152. ISBN 978-0-521-52446-9.

- ^ Davies, Carole Boyce (29 July 2008). Encyclopedia of the African Diaspora [3 volumes]: Origins, Experiences, and Culture [3 volumes]. Santa Barbara, California: Bloomsbury Publishing USA. pp. 848–849. ISBN 978-1-85109-705-0.

- ^ Lubabu, Muitubile K. Tshitenge (4 June 2013). "Congo: rhythm and blues". Jeuneafrique.com (in French). Paris, France. Retrieved 20 April 2024.

- ^ Malu-Malu, Muriel Devey (20 September 2020). "Congo-B : Que sont les célèbres bars dancing devenus ?" [Congo-B: What have become of the famous dancing bars?]. Makanisi.org (in French). Retrieved 20 April 2024.

- ^ Martin, Phyllis (8 August 2002). Leisure and Society in Colonial Brazzaville. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. pp. 131–152. ISBN 978-0-521-52446-9.

- ^ Assah, Hervé (29 March 2022). Lumineuse Afrique : Améringo, l'héritage inattendu Tome 2 (in French). Paris, France: Éditions L'Harmattan. p. 39. ISBN 978-2-14-023977-9.

- ^ Mukuna, Kazadi wa (7 December 2014). "A brief history of popular music in DRC". Music in Africa. Retrieved 25 August 2023.

- ^ wa Mukuna, Kazadi (1992). "The Genesis of Urban Music in Zaïre". African Music. 7 (2). Grahamstown, Eastern Cape, South Africa: International Library of African Music: 72–84. doi:10.21504/amj.v7i2.1945. ISSN 0065-4019. JSTOR 30249807.

- ^ White, Bob W. (1 January 2002). "Congolese Rumba and Other Cosmopolitanisms". Cahiers d'Études Africaines. 42 (168): 663–686. doi:10.4000/etudesafricaines.161. ISSN 0008-0055.

- ^ N'Sial, Sesep (1975). "Pour une approche d'une variable du plurilinguisme: la conjonction du français et du lingala dans le discours spontané" [Toward an approach to a variable of plurilingualism: the conjunction of French and Lingala in spontaneous speech]. Collection IDERIC (in French). 2 (1). Persée: 15–33. doi:10.3406/bcepl.1975.856.

- ^ Stewart, Gary (17 November 2003). Rumba on the River: A History of the Popular Music of the Two Congos. Verso Books. pp. 134–136. ISBN 978-1-85984-368-0.

- ^ Bemba, Audifax (14 October 2023). "Orchestre Sinza "Kotoko" de Brazzaville" [Sinza "Kotoko" Orchestra of Brazzaville]. Congopage (in French). Retrieved 31 August 2024.

- ^ Falola, Toyin; Jean-Jacques, Daniel (14 December 2015). Africa: An Encyclopedia of Culture and Society [3 volumes]. Santa Barbara, California, United States: ABC-Clio. ISBN 979-8-216-04273-0.

- ^ Kabwe, Jason (15 March 2013). "Ndombolo Craze". Czech Radio (in Czech). Retrieved 9 November 2023.

- ^ Sörgel, Sabine (30 March 2020). Contemporary African Dance Theatre: Phenomenology, Whiteness, and the Gaze. Springer Nature. p. 55. ISBN 978-3-030-41501-3.

- ^ Tchebwa, Manda (30 November 2002). "N'Dombolo: the identity-based postulation of the post-Zaïko generation" [N'Dombolo: the identity-based postulation of the post-Zaïko generation]. Africultures (in French). Paris, France. Retrieved 13 January 2024.

- ^ a b Mongrue, Jesse (10 June 2016). What's Working in Africa?: Examining the Role of Civil Society, Good Governance, and Democratic Reform. Bloomington, Indiana, United States: iUniverse. ISBN 978-1-4917-9501-9.

- ^ Mutara, Eugene (29 April 2008). "allAfrica.com: Rwanda: Memories Through Congolese Music (Page 1 of 1)". The New Times. Kigali, Rwanda. Archived from the original on 5 September 2008. Retrieved 29 July 2025.

- ^ a b c d e Martin, Phyllis (8 August 2002). Leisure and Society in Colonial Brazzaville. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. pp. 131–152. ISBN 978-0-521-52446-9.

- ^ Okamba, Emmanuel (30 March 2022). "La "Rumba", un humanisme musical en partage" (in French). Lyon, France: HAL. p. 5. Retrieved 15 December 2023.

- ^ a b Mukuna, Kazadi wa (7 December 2014). "A brief history of popular music in DRC". Music in Africa. Retrieved 25 August 2023.

- ^ wa Mukuna, Kazadi (1992). "The Genesis of Urban Music in Zaïre". African Music. 7 (2): 72–84. doi:10.21504/amj.v7i2.1945. ISSN 0065-4019. JSTOR 30249807.

- ^ Diop, Jeannot Ne Nzau (14 May 2005). "Congo-Kinshasa : Evolution de la musique congolaise moderne de 1930 à 1950" [Congo-Kinshasa: Evolution of modern Congolese music from 1930 to 1950]. Le Potentiel (in French). Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of the Congo. Retrieved 24 May 2025.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac Tsambu, Leon. "Section 1.-1930-1950: de l'agbaya à l'ère de la musique populaire moderne pionnière" [Section 1.-1930-1950: from agbaya to the era of modern popular musicpioneer]. Bokundoli (in French). Retrieved 30 November 2023.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Okamba, Emmanuel (30 March 2022). "La "Rumba", un humanisme musical en partage" (in French). Lyon, France: HAL. p. 8. Retrieved 18 December 2023.

- ^ The Encyclopedia of Africa v. 1. 2010 p. 407.

- ^ Storm Roberts, John (1999). The Latin Tinge: The Impact of Latin American Music on the United States (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Oxford University Press. pp. 217–218. ISBN 978-0-19-976148-7.

- ^ a b Chicago Tribune (2 June 1993). "American listeners are discovering Soukous". Chicago Tribune. Chicago, Illinois, United States. Retrieved 11 June 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k wa Mukuna, Kazadi (1992). "The Genesis of Urban Music in Zaïre". African Music. 7 (2). Grahamstown, Eastern Cape, South Africa: International Library of African Music: 79–81. ISSN 0065-4019.

- ^ Ossinondé, Clément (27 September 2019). "Congo-Brazzaville - Guy Léon Fylla: Le souvenir d'une grande légende de la musique congolaise 4 ans après sa disparition" [Congo-Brazzaville - Guy Léon Fylla: The memory of a great legend of Congolese music 4 years after his disappearance]. Congopage (in French). Retrieved 26 April 2024.

- ^ Ossinondé, Clément (7 September 2019). "Les deux premiers grands orchestres de cuivres de Brazzaville et de Kinshasa en 1940" [The first two major brass orchestras of Brazzaville and Kinshasa in 1940]. Zenga-mambu.com (in French). Retrieved 26 April 2024.

- ^ a b Ossinondé, Clément (13 January 2020). "La genèse de la production musicale, des droits d'auteur, du syndicat d'artistes-musiciens à Léopoldville (Kinshasa) de 1947 à 2019" [The genesis of musical production, copyright, and the union of artists-musicians in Léopoldville (Kinshasa) from 1947 to 2019]. Congopage (in French). Retrieved 4 September 2024.

- ^ Okamba, Emmanuel (30 March 2022). "La "Rumba", un humanisme musical en partage" (in French). Lyon, France: HAL. p. 9. Retrieved 18 December 2023.

- ^ Greenstreet, Morgan (7 December 2018). "Seben Heaven: The Roots of Soukous". daily.redbullmusicacademy.com. Retrieved 11 June 2024.

- ^ Stewart, Gary (17 November 2003). Rumba on the River: A History of the Popular Music of the Two Congos. Verso. pp. 24–33. ISBN 978-1-85984-368-0.

- ^ a b c d Ossinondé, Clément (10 February 2011). "Joseph Kabasele: 28 ans après sa disparition" [Joseph Kabasele: 28 years after his disappearance]. Mbokamosika (in French). Retrieved 14 August 2025.

- ^ a b Ossinonde, Clément (12 October 2020). "Dossier - Luambo-Makiadi "Franco", comme vous ne l'avez jamais connu" [File - Luambo-Makiadi "Franco", as you never knew him]. Congopage (in French). Retrieved 22 August 2024.

- ^ a b c d Ossinondé, Clément (3 June 2011). "PBL vox: L'O.K. JAZZ L'une des très belles réussites musicales Congolaises des 55 dernières années (06 Juin 1956 – 06 Juin 2011)" [PBL vox: OK JAZZ – One of the finest Congolese musical achievements of the past 55 years (6 June 1956 – 6 June 2011)]. PBL vox. Retrieved 12 July 2025.

- ^ Brouns, Arthur (13 February 2020). "Le label belge qui ressuscite la rumba congolaise des années 1950 à 1970" [The Belgian label that revives Congolese rumba from the 1950s to the 1970s]. Vice (in French). Retrieved 13 April 2025.

- ^ Nascimento, Evelyn Rosa do (25 June 2021). ""O Dipandatcha-tchaTozui e": história e conexões culturais através da rumba congolesa (1940–1965)" ["O Dipandatcha-tchaTozui e": history and cultural connections through the Congolese rumba (1940–1965)] (PDF) (in Portuguese). Rio de Janeiro: Pontifical Catholic University of Rio de Janeiro. p. 11. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 May 2022. Retrieved 21 April 2024.

- ^ Brouns, Arthur (13 February 2020). "Le label belge qui ressuscite la rumba congolaise des années 1950 à 1970" [The Belgian label that revives Congolese rumba from the 1950s to the 1970s]. Vice (in French). Retrieved 13 April 2025.

- ^ Ossinondé, Clément (5 October 2009). "Le souvenir de Luambo Makiadi Franco et l'Ok Jazz" [The memory of Luambo Makiadi Franco and Ok Jazz]. Congopage (in French). Retrieved 22 August 2024.

- ^ Nascimento, Evelyn Rosa do (25 June 2021). ""O Dipandatcha-tchaTozui e": história e conexões culturais através da rumba congolesa (1940–1965)" ["O Dipandatcha-tchaTozui e": history and cultural connections through the Congolese rumba (1940–1965)] (PDF) (in Portuguese). Rio de Janeiro: Pontifical Catholic University of Rio de Janeiro. p. 11. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 May 2022. Retrieved 21 April 2024.

- ^ Dumitrescu, Irina (2016). Rumba Under Fire: The Arts of Survival from West Point to Delhi. Santa Barbara, California, United States.: Punctum Books. p. 206. ISBN 978-0-692-65583-2.

- ^ Dibango, Manu (3 October 1994). Three Kilos of Coffee: An Autobiography. Chicago, Illinois, United States: University of Chicago Press. pp. 23–33. ISBN 978-0-226-14490-0.

- ^ Nascimento, Evelyn Rosa do (25 June 2021). ""O Dipandatcha-tchaTozui e": história e conexões culturais através da rumba congolesa (1940–1965)" ["O Dipandatcha-tchaTozui e": history and cultural connections through the Congolese rumba (1940–1965)] (PDF) (in Portuguese). Rio de Janeiro: Pontifical Catholic University of Rio de Janeiro. p. 11. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 May 2022. Retrieved 21 April 2024.

- ^ Guinard, Clémence (13 January 2022). "La Rumba congolaise, la musique de l'indépendance (et de la SAPE)" [Congolese Rumba, the music of independence (and of the SAPE)]. Radio France (in French). Paris, France. Retrieved 13 April 2025.

- ^ Seck, Nago (10 May 2007). "TP OK Jazz". Afrisson (in French). Retrieved 14 August 2025.

- ^ Schnabel, Tom (4 August 2020). "Spotlight on Congolese Superstar Franco". KCRW. Santa Monica, California, United States. Retrieved 14 August 2025.

- ^ Millward, Stephen (1 December 2012). Changing Times: Music and Politics in 1964. Leicestershire, England: Troubador Publishing Ltd. p. 231. ISBN 978-1-78088-344-1.

- ^ a b c Lavaine, Bertrand (16 August 2013). "Succès, trahisons et création dans la rumba" [Success, betrayals and creation in rumba]. Radio France Internationale (in French). Paris, France. Retrieved 14 August 2025.

- ^ a b Stewart, Gary (June 1992). Breakout: Profiles in African Rhythm. Chicago, Illinois, United States: University of Chicago Press. pp. 22–25. ISBN 978-0-226-77406-0.

- ^ a b Smith, C.C. (5 July 2018). "Afropop Worldwide | Best of the Beat on Afropop: Leo Sarkisian and Mwamba Dechaud". Afropop Worldwide. Brooklyn, New York, New York, United States. Retrieved 28 October 2023.

- ^ Mwenze (1 July 2016). "Chronologie des solistes de l'orchestre Afrisa International de Tabu Ley Rochereau" [Chronology of the soloists of the Afrisa International Orchestra of Tabu Ley Rochereau]. Mbokamosika (in French). Retrieved 14 August 2025.

- ^ Braun, Ken. "Seigneur Rochereau Tabu Ley". Rootsworld.com. Retrieved 14 August 2025.

- ^ Seck, Nago (10 January 2007). "Pascal-Emmanuel Sinamoyi Tabu: Tabu Ley Rochereau". Afrisson (in French). Retrieved 14 August 2025.

- ^ a b c d di Perna, Alan (9 December 2021). "The story of Africa's guitar god Dr. Nico, the Congolese innovator admired by Jimi Hendrix". Guitar World. New York, New York, United States. Retrieved 14 August 2025.

- ^ Ossinonde, Clément (12 October 2020). "Dossier - Luambo-Makiadi "Franco", comme vous ne l'avez jamais connu" [File - Luambo-Makiadi "Franco", as you never knew him]. Congopage (in French). Retrieved 22 August 2024.

- ^ Nkenkela, Auguste Ken (19 January 2024). "Les souvenirs de la musique congolaise : biographie et discographie de Luambo Makiadi Franco" [Memories of Congolese Music: Biography and Discography of Luambo Makiadi Franco]. Adiac-congo.com (in French). Brazzaville, Republic of the Congo. Retrieved 19 May 2025.

- ^ "Olivier Tshimanga explique les différences entre l'école Odemba et l'école Fiesta" [Olivier Tshimanga explains the differences between the Odemba school and the Fiesta school]. Mbote (in French). Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of the Congo. 8 March 2023. Retrieved 19 May 2025.

- ^ Brun, Bastien (26 September 2018). "Dizzy Mandjeku: grand maitre de la guitare rumba" [Dizzy Mandjeku: Grand Master of Rumba Guitar]. Pan African Music (in French). Retrieved 14 August 2025.

- ^ Cagnolari, Vladimir (16 February 2021). "Mangwana, le roman d'une vie: le Maquisard de l'African Fiesta" [Mangwana, the novel of a lifetime: the Maquisard of the African Fiesta]. Pan African Music (in French). Retrieved 14 August 2025.

- ^ Cagnolari, Vladimir (22 February 2021). "Mangwana, le roman d'une vie: et Sam devint OK… Jazz!" [Mangwana, the novel of a lifetime: and Sam became OK… Jazz!]. Pan African Music (in French). Retrieved 14 August 2025.

- ^ Bessem, Frank (January 2002). "Musiques d'Afrique/D.R. Congo: Sam Mangwana". Musiques-afrique.net. Retrieved 14 August 2025.

- ^ Diop, Jeannot Ne Nzau (21 May 2005). "Congo-Kinshasa: Evolution de la musique congolaise moderne des années 1960 et 1970" [Congo-Kinshasa: Evolution of modern Congolese music of the 1960s and 1970s]. Le Potentiel (in French). Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of the Congo. Retrieved 16 August 2025.

- ^ Seck, Nago (19 December 2020). "The Congo Acoustic". Afrisson (in French). Retrieved 16 August 2025.

- ^ Clerfeuille, Sylvie (7 May 2007). "Mose Se Sengo (Mose Fan Fan)". Afrisson (in French). Retrieved 16 August 2025.

- ^ "Auteur de "Dje Melasi", Fanfan Mose est décédé le 3 mai 2019 à Nairobi" [Author of "Dje Melasi", Fanfan Mose died on 3 May 2019 in Nairobi]. Mbokamosika (in French). 5 May 2019. Retrieved 16 August 2025.

- ^ "Mose Se Sengo (Fan Fan)". Music In Africa (in French). 3 June 2014. Retrieved 16 August 2025.

- ^ Anheier, Helmut K.; Isar, Yudhishthir R., eds. (21 January 2010). Cultures and Globalization: Cultural Expression, Creativity and Innovation. Thousand Oaks, California: SAGE Publications. p. 119. ISBN 9780857026576.

- ^ Salter, Thomas (January 2007). "Rumba from Congo to Cape Town". Edinburgh, Scotland, United Kingdom: University of Edinburgh. pp. 1–30. Retrieved 7 May 2024.

- ^ Micalef, Olivier Rivera (July 2024). "Tradition et modernité dans la musique de l'Afrique occidentale" [Tradition and Modernity in the Music of West Africa] (PDF). Digibuo.uniovi.es (in French). Oviedo, Asturias, Spain: University of Oviedo. p. 17. Retrieved 30 July 2025.

- ^ a b "The Congolese People: A Cultural Profile of the Democratic Republic of the Congo – Music and Dance". Culturaldiversityresources. 6 January 2022. Retrieved 16 August 2025.

- ^ "Orchestre Les Thu Zahina". Radiodiffusion Internasionaal Annexe. 31 March 2024. Retrieved 16 August 2025.

- ^ Lavaine, Bertrand (30 October 2024). "Zaïre 74, un festival pour l'histoire" [Zaire 74, a festival for history]. Radio France Internationale (in French). Paris, France. Retrieved 16 August 2025.

- ^ "E-Journal Kinshasa: Hebdomadaire d'informations générales, des programmes TV, Radio et Publicité, No. 0039" (PDF). E-journal.info (in French). Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of the Congo: E-journal Kinshasa. 30 May 2020. pp. 12–13. Retrieved 16 August 2025.

- ^ "Thu Zahina" (PDF). Afrodisc.com (in English, French, and Japanese). 2020. p. 1–4. Retrieved 16 August 2025.

- ^ Nickel, Antoine (23 August 2008). "La stratégie de Lita Bembo pour détrôner le Zaïko ..." [Lita Bembo's strategy to dethrone Zaïko...]. Mbokamosika (in French). Retrieved 17 August 2025.

- ^ Bayo, Herman Bangi (18 August 2020). "Tabu Ley: parrain des orchestres de la 3e génération" [Tabu Ley: Godfather of 3rd Generation Orchestras]. E-Journal Kinshasa (in French). Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of the Congo. Retrieved 17 August 2025.

- ^ Mafina, Frédéric (18 August 2023). "Les immortelles chansons d'Afrique: "Gida" de Lita Bembo" [The immortal songs of Africa: "Gida" by Lita Bembo]. Adiac-congo.com (in French). Brazzaville, Republic of the Congo: Agence d'Information d'Afrique Centrale. Retrieved 17 August 2025.

- ^ a b c Diop, Jeannot Ne Nzau (21 May 2005). "Congo-Kinshasa: Evolution de la musique congolaise moderne des années 1960 et 1970" [Congo-Kinshasa: Evolution of modern Congolese music of the 1960s and 1970s]. Le Potentiel (in French). Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of the Congo. Retrieved 17 August 2025.

- ^ a b "Zaiko Langa Langa: The most Illustrious band in Africa". Kenya Page. Nairobi, Kenya. 15 February 2025. Retrieved 17 August 2025.

- ^ Francois, Francois (8 September 2020). "Zaïko Langa-Langa: nouvel album "Sève"" [Zaïko Langa-Langa: new album "Sève"]. Paris Move (in French). Paris, France. Retrieved 17 August 2025.

- ^ Yunduka, Karim (9 October 2020). "50 ans d'existence: Zaïko Langa Langa renaît de ses cendres" [50 years of existence: Zaïko Langa Langa rises from its ashes]. Adiac-congo.com (in French). Brazzaville, Republic of the Congo: Agence d'Information d'Afrique Centrale. Retrieved 17 August 2025.

- ^ "Congo-Kinshasa: Kinshasa s'est souvenu d'Emile et Maxime Soki" [Congo-Kinshasa: Kinshasa remembers Emile and Maxime Soki]. Le Potentiel (in French). Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of the Congo. 8 May 2010. Retrieved 24 May 2025.

- ^ Mafina, Frédéric (30 August 2024). "Les immortelles chansons d'Afrique: "Shama Shama" de Mopero wa Maloba" [The immortal songs of Africa: "Shama Shama" by Mopero wa Maloba]. Adiac-congo.com (in French). Brazzaville, Republic of the Congo: Agence d'Information d'Afrique Centrale. Retrieved 17 August 2025.

- ^ a b c d e Levi, Ron (4 May 2017). "Zaire '74: politicising the sound event". Social Dynamics: A Journal of African Studies. 43 (2): 184–198. doi:10.1080/02533952.2017.1364469. ISSN 0253-3952.

- ^ Davies, Carole Boyce (29 July 2008). Encyclopedia of the African Diaspora [3 volumes]: Origins, Experiences, and Culture. New York City, New York State, United States: Bloomsbury Publishing USA. p. 849. ISBN 978-1-85109-705-0.

- ^ Trillo, Richard (2016). The Rough Guide to Kenya. London, United Kingdom: Rough Guides. p. 598. ISBN 9781848369733.

- ^ Stewart, Gary (5 May 2020). Rumba on the River: A History of the Popular Music of the Two Congos. Brooklyn, New York City, New York State: Verso Books. ISBN 978-1-78960-911-0.

- ^ Valdés, Vanessa K., ed. (June 2012). Let Spirit Speak!: Cultural Journeys Through the African Diaspora. Albany, New York City, New York State: State University of New York Press. pp. 40–41. ISBN 9781438442174.

- ^ Hodgkinson, Will (8 July 2010). "How African music made it big in Colombia". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 23 August 2023.

- ^ Falola, Toyin; Jean-Jacques, Daniel (14 December 2015). Africa [3 Volumes]: An Encyclopedia of Culture and Society [3 Volumes]. London, England, United Kingdom: Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 979-8-216-04273-0.

- ^ Falola, Toyin; Jean-Jacques, Daniel (14 December 2015). Africa [3 Volumes]: An Encyclopedia of Culture and Society [3 Volumes]. London, England, United Kingdom: Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 979-8-216-04273-0.

- ^ Davies, Carole Boyce (29 July 2008). Encyclopedia of the African Diaspora [3 volumes]: Origins, Experiences, and Culture. New York City, New York State, United States: Bloomsbury Publishing USA. p. 849. ISBN 978-1-85109-705-0.

- ^ Mutara, Eugene (29 April 2008). "Rwanda: Memories Through Congolese Music". The New Times. Retrieved 27 July 2024.

- ^ Bangré, Habibou (26 April 2016). "Les sapeurs de Kinshasa se disputent l'héritage de Papa Wemba" [Kinshasa sappers fight over Papa Wemba's legacy]. Le Monde (in French). Paris, France. Retrieved 17 August 2025.

- ^ Cagnolari, Vladimir (18 August 2016). "Une musique, une histoire: "Sapologie", Papa Wemba [Comme un roman]" [A music, a story: "Sapologie", Papa Wemba [Like a novel]]. Pan African Music (in French). Retrieved 17 August 2025.

- ^ Enrica (26 April 2016). "Papa Wemba, le Pape de la Sape". Afrosartorialism. Retrieved 17 August 2025.

- ^ Sonsa-Kini, Kevin (16 August 2025). "L'évolution de la rumba congolaise partie 5: Papa Wemba et l'esthétique de la SAPE" [The Evolution of Congolese Rumba Part 5: Papa Wemba and the Aesthetics of SAPE]. Culture & Passions (in French). Retrieved 17 August 2025.

- ^ Kiakesidi, Benjamin Mbangu; Nzugu, Patricia (12 May 2011). "Congo-Kinshasa: L'ancien artiste musicien de Zaiko langa langa, Bimi sera enterré aujourd'hui" [Congo-Kinshasa: Former Zaiko Langa Langa musician Bimi to be buried today]. Lephareonline.net (in French). Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of the Congo. Retrieved 13 July 2024.

- ^ E., Martin; Ipan, B. (23 June 2011). "Congo-Kinshasa: La musique congolaise en deuil - Mbuta Mashakado s'est éteint en Afrique du Sud" [Congo-Kinshasa: Congolese music in mourning - Mbuta Mashakado died in South Africa]. Lepotentiel.cd (in French). Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of the Congo. Retrieved 13 July 2024.

- ^ Diala, Jordache (28 August 2015). "Congo-Kinshasa: 15 ans après la mort de l'artiste - 60% de jeunes kinois ne connaissent pas Dindo Yogo!" [Congo-Kinshasa: 15 years after the artist's death - 60% of young Kinshasa residents do not know Dindo Yogo!]. Laprosperiteonline.net (in French). Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of the Congo. Retrieved 14 July 2024.

- ^ Makombo, Jean-Marie Mutamba (31 March 2007). "Congo-Kinshasa: La rumba revient en force au pays de Ndombolo" [Congo-Kinshasa: Rumba returns in force to the land of Ndombolo]. Le Potentiel (in French). Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of the Congo. Retrieved 17 August 2025.

- ^ Kazadi, Désiré-Israël (8 November 2002). "Congo-Kinshasa: Tshala Muana se déchaîne dans une explosion de "mutuashi"" [Congo-Kinshasa: Tshala Muana unleashes an explosion of "mutuashi"]. Le Potentiel (in French). Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of the Congo. Retrieved 17 August 2025.

- ^ "Danse mutuashi". Africamuseum.be (in French). Tervuren, Flemish Brabant, Belgium: Royal Museum for Central Africa. 19 July 2025. Retrieved 17 August 2025.