Mont Chaberton

| Mont Chaberton | |

|---|---|

Southeast face of Chaberton | |

| Highest point | |

| Elevation | 3,131 m (10,272 ft)[1] |

| Prominence | 1,281 m (4,203 ft)[1] |

| Parent peak | Pic de Rochebrune[1] |

| Isolation | 12.21 km (7.59 mi) |

| Listing | Alpine mountains above 3000 m |

| Coordinates | 44°57′53″N 6°45′04″E / 44.96472°N 6.75111°E |

| Geography | |

Mont Chaberton France | |

| Location | Hautes-Alpes, France |

| Parent range | Cottian Alps |

Mont Chaberton (French pronunciation: [mɔ̃ ʃabɛʁtɔ̃]) is a 3,131 metres (10,272 ft) peak in the French Alps in the group known as the Massif des Cerces in the département of Hautes-Alpes.

Before World War I, Italy built Europe's highest fortress on the top. The French destroyed it in 1940, and acquired the whole mountain by Peace Treaty of 1947. Fort and mountain became a popular tourist destination as the deteriorating military road to the top could be used legally until 1987 even with some offroad cars. Access by offroad motorcycles was prevented by landslides in the late 2010s.

Geography

The mountain is located close to the main chain of the Alps where it marks the Dora-Durance water divide, on the eastern side of it. The Col du Chaberton (2.674 m) connects the Chaberton with the Pointe Rochers Charniers and the main ridge.[2] Chaberton is in the municipality of Montgenèvre in the Briançonnais natural region. It is easily recognisable by its pyramidal shape and flattened top with a "crown" of eight towers.

History

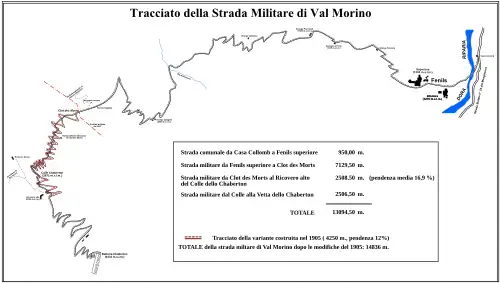

In 1883 Italy joined the Triple Alliance and started strengthening its defences against France. Between 1898 and 1910, Italian troops built an access road for Pack animals, barracks for workers, and finally an artillery battery on the summit that pointed towards France, particularly at the town of Briançon, and the pass over the Col de Montgenèvre. The road to the summit was built from the village of Fénils in the Susa Valley by soldiers and engineers led by Major Engineer Luigi Pollari Maglietta. They flattened the summit by about 6 metres to provide a surface for the eight towers. Their height of 12 metres was designed to overcome the highest snowfall recorded.

Each emplacement was manned by seven men, who were protected by a relatively lightly armoured dome because the battery was thought to be out of reach of pre-WW1 conventional artillery. Eight 149mm guns were mounted in the individual masonry towers.[3] The fort was dubbed the "Fort of the Clouds" or "Battleship in the Clouds".

During the First World War, Italy allied with France alongside the Triple Entente and entered the war against the Austro-Hungarian Empire. The guns were removed to be used on the Italian front. After the Great War, which was fought in trenches only on the Western front of Germany, but quite mobile in the East, some Western countries built border fortifications. As part of the French Maginot Line sector 24 Alpine Line, forts were built near Briançon, and the Alpine Wall was built under the Benito Mussolini's regime.

Monte Chaberton was rearmed again. In the upper section of the road, the sweeping turns were shortened as beasts of burden were replaced by motor vehicles that could handle steeper roads, both ways. An Aerial lift was added, too. Due to threats by airplanes and modern artillery, caves were built for better protection of the troops.

In May 1940, the Battle of France was fought, and Paris would fall to the Germans on 14 June. On 5 June, Mussolini told Badoglio, "I only need a few thousand dead so that I can sit at the peace conference as a man who has fought".[4] The Italians felt a need to help with winning, and declared war on France and Britain on June 10, fighting mostly air campaigns and remaining defensive. After the French Government collapsed and a cease-fire was discussed, on 16 June, offensive Operation M through the Maddalena Pass and other operations were planned.[5] That day, elements of the Italian 4th Army attacked in the vicinity of Briançon. As the Italians advanced, the French at Fort de l'Olive began bombarding the Italian Fort Bardonecchia. In retaliation, the 149-mm guns of the "imposing structure lost in the clouds at an altitude of 3,130 meters"—were trained on Fort de l'Olive which silenced the French fort the following day.[6]

Just before France would sign an armistice, an Italian invasion of France was launched on 21 June 1940. At that time, the Chaberton garrison had about 340 men under the command of Captain Spartaco Bevilacqua, and had fired on 18 June on Ouvrage Gondran and other targets, causing minor damage due to lack of precision. In the meantime, the French army installed four Schneider 280mm mortars dating back to the battle of Verdun in the First World War, divided into two batteries, both camouflaged and outside the direct view of the Italians: one at the Position de l'Eyrette, right below Fort de l'Infernet, the other as Position du Poët-Morand[7] in the nearby village of Pouet-Morand. These two sections were manned by the 6th Battery of the 154th Régiment d'Artillerie de Position (154th RAP) under lieutenant André Miguet. Because of the 1000m altitude differences of the mortars and their target some 10 km away, regular artillery tables were insufficient. General Georges Marchand ordered his engineers to calculate and test special artillery tables.

Chaberton again bombarded the French positions around Briançon on 20 June, but Italian troops did not advance. Little damage was inflicted. Because of clouds on the peak, the French could not respond yet. When the cloud cover opened in the afternoon of 21 June 1940 the 154th Artillery Regiment, using their mortars and guided by observers on the nearby Ouvrage Janus and other places, fired at Chaberton. The first shot was short, the second destroyed the lift and electric power supply, others were on target. They destroyed six of the eight turrets, nine Italians were killed and 50 were wounded. Turrets 7 and 8 continued to fire over the next three days, until the cease-fire of 24 June 1940. During the short warfare in the summertime Alps, the Italian side not only inflicted and suffered military losses, but also had 2,151 frostbite victims.

The fort was not repaired, and abandoned on 8 September 1943. It was briefly re-occupied in the autumn of 1944 by paratroopers of the Italian Social Republic observing the allied Advance.

At the end of the war, the Chabertonism of Charles de Gaulle demanded the symbolic mountain, and by the Treaty of Paris between Italy and the Allied Powers, the border was moved[8] to the edge of the Italian village of Claviere, which was divided until 1974, then reunited. In 1957 all the military remains, guns and armour were removed. The masonry that supported the turrets is still visible. The remaining underground structures are in a dangerous condition.

Military road

The unpaved „Strada militare di Val Morino“ with 72 hairpin bends and 14 kilometre length from Fénils (1276m above sea level) was described in various guides to Alpine roads, namely the Austrian „Denzel“, which used superlatives. In the 1970s, touring motorcycles and small cars could reach the mountain top, the size limited by the bottle neck at the split rock (Roccia Tagliata 2370m). Due to an annual Italian memorial event, the road was usually repaired to a small degree, but fell into disrepair anyway, making the challenge harder. Motor vehicles were officially forbidden in 1987, but many tourists still rode it with Enduro motorcycles. Some took pictures and videos, which became more common in the 2000s. There are countless Chaberton reports and videos on social media.

After some inhabited places, the gravel part begins at Pra Claud (1589m), and already at Rio dell Inferno (1960m) landslides have destroyed the road in the 2010s. Since, only pedestrians can pass it carefully, some are carrying mountain bikes.

Already in the 1990s, the section above Grange Quagliet, with steep and narrow washed out bends, littered with rocks and loose gravel, prevented some riders from getting themselves deeper resp. higher in trouble. As the whole medium part is on the East side of the mountain, it is sunlight before noon, and will be in the shade when returning downhill in the afternoon. A level quarter mile long passage along the hill side leads to the split rock, which kind of extended its bottle neck to smaller vehicles as erosion narrowed down the ledge. A rope was fixed to the mountainside to help passing the gap.

Behind the rock, the relatively wide Valley of the Dead begins, now situated in France and called Clot des Morts. Another groups of tight bends leads to the Colle del Chaberton pass, 2671 m high. There are still some 500m of height difference to the mountain top. As the "road", or what is left of it, is on the North side of the mountain, remnants of old snow, or new, might block the way.

-

Chaberton in Winter as seen from Susa

Chaberton in Winter as seen from Susa -

Mont Chaberton as seen from Desertes

Mont Chaberton as seen from Desertes -

Scheme of 1934 (44/43 for aerial lift)

Scheme of 1934 (44/43 for aerial lift) -

Remnants

-

View down on pass and road

View down on pass and road

Geology

The portion closest to the peak is composed of white and yellowish dolomite dating back to the upper Late Triassic; moving away from the summit there are formations of limestone and compact dolomite and grey limestone shale, limestone of the Jurassic in a structure syncline. On the ridge between the summit and the nearby are outcrops of mica schist with quartz, crystalline limestones and porphyritic rocks.

References

- ^ a b c "Mont Chaberton". Peakbagger.com. Retrieved 2014-01-01.

- ^ Géoportail (Map) (in French). IGN. Retrieved 2019-04-05.

- ^ Kauffmann, J.E.; Kauffmann, H.W.; Jancovič-Potočnik, A.; Lang, P.; Jacques (2011). The Maginot Line: History and Guide. Pen and Sword. p. 155. ISBN 978-1-84884-068-3.

- ^ Badoglio 1946, p. 37.

- ^ Stefani 1985, pp. 108–09.

- ^ Kaufmann & Kaufmann 2007, p. 177.

- ^ La Bataille du Chaberton (1940) : l'exploit hors-norme de l'artillerie française https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yFSyowiJ-Zo&t=1490

- ^ "3. Mont Thabor-Chaberton (a) In the Mont Thabor area, the frontier shall leave the present frontier about 5 kilometers to the east of Mont Thabor and run southeastward to rejoin the present frontier about 3 kilometers west of the Pointe de Charra. (b) In the Chaberton area, the frontier shall leave the present frontier about 3 kilometers north-northwest of Chaberton, which it skirts on the east, and shall cross the road about 1 kilometer from the present frontier, which it rejoins about 2 kilometers southeast of the village of Montgenevre"

Bibliography

- Kaufmann, J. E.; Kaufmann, H. W. (2007). Fortress France: The Maginot Line and French Defenses in World War II. Stackpole Military History Series. Stackpole Books. ISBN 978-0-811-73395-3.

- Schiavon, Max (2007). Une victoire dans la défaite - La destruction du Chaberton, Briançon 1940. Éditions Anovi. ISBN 2-914818-18-1

- Stefani, Filippo (1985). La storia della dottrina e degli ordinamenti dell'Esercito italiano, t. 1o: Da Vittorio Veneto alla 2a guerra mondiale, no. 2o: La 2a guerra mondiale, 1940–1943. Rome: Stato maggiore dell'Esercito.