Mishaguji

.jpg)

Mishaguji (御左口神, 御社宮司, 御射宮司, 御社宮神; katakana: ミシャグジ), also known as Misakuji(n), Mis(h)aguchi or Mishakuji among other variants (see below), is a collective term for deities or spirits (kami) venerated in the Suwa region of Nagano Prefecture, particularly associated with the ritual practices of the Upper Shrine (Kamisha) of Suwa Taisha. These spirits once played a key role in the shrine’s winter and spring religious ceremonies and are also enshrined in numerous smaller shrines throughout the region. In these ceremonies, the Kan-no-Osa or Jinchō (神長) — also known as Jinchōkan (神長官) — a high-ranking ritual priest from the Moriya clan, would summon the Mishaguji into vessels (yorishiro), such as individuals or objects, to be temporarily inhabited during the rite. Upon completion, the spirits were ritually dismissed.

Despite their longstanding presence in local tradition, the precise nature and original characteristics of the Mishaguji remain elusive, and no single definitive explanation has been established. Documents produced by the Moriya during the medieval period portray the Mishaguji (御左口神) as lesser deities who form the retinue of Suwa Myōjin (a.k.a. Takeminakata), the deity of Suwa Shrine. By the early modern period, “Mishaguji” came to be interpreted in Suwa as an umbrella term for local kami who were revered as Suwa Myōjin's children (御子神, mikogami).

In the early 20th century, folklorists such as Kunio Yanagita and Nogiku Imai observed similarities between Suwa's Mishaguji worship and ishigami / shakujin (石神, "stone deity", beliefs centered around unusual or spiritually charged stones) traditions found elsewhere in east and central Japan, as well as roadside deity cults such as Sai-no-Kami and Dōsojin, found in parts of the Kantō and Kinki regions. These scholars proposed that such beliefs formed part of a widespread, interconnected religious complex, leading to the adoption of the broad category "Mishaguji belief" (ミシャグジ信仰, Mishaguji-shinkō) to encompass these various traditions. While this classification was widely accepted through much of the 20th century, more recent scholarship has emphasized the need to distinguish Suwa’s Mishaguji from other, superficially similar local cults.

The postwar period brought increased scholarly interest in the Mishaguji, and numerous theories emerged regarding their origins and relationship to Suwa Shrine. Some proposed that Mishaguji were originally fertility or agricultural deities, while others viewed them as spirits inhabiting sacred natural objects, such as rocks or trees. Another theory held that “Mishaguji” denoted a more abstract, impersonal vital force, akin to the Austronesian concept of mana, a spiritual power present in people, objects, and landscapes.

Some theories posit that Mishaguji worship may trace its origins to the Jōmon period, given that the Suwa basin was a flourishing center of Jōmon culture and that many Mishaguji shrines incorporate Jōmon-era phallic stone rods (石棒 sekibō) and similar prehistoric artifacts as sacred objects. Additionally, the archaic nature of certain Suwa Shrine rituals hint at an ancient origin. Certain scholars have thus proposed that Mishaguji worship preserves remnants of an earlier animistic tradition predating the emergence of Takeminakata worship in the region, viewing the Mishaguji's presence at the Upper Shrine's rites as vestiges of original local beliefs. However, this interpretation has faced recent criticism, with some experts cautioning against overly speculative correlations between archaeological artifacts and later religious practices.

Names

Multiple variants of the name 'Mishaguji' exist such as 'Mishaguchi', 'Misaguchi', 'Misaguji', 'Mishakuji', 'Misakuji(n)', or 'Omishaguji'.[1][2][3][4][5][6][7] There are also various ways of rendering the name in kanji such as 御左口神, 御作神, 御社宮神, or 御社宮司, with 御左口神 being the commonly used form in medieval documents penned by the Suwa Shrine priesthood.[8] Outside Suwa, deities thought to be related to the Mishaguji with names such as '(O)shaguji', '(O)shagoji', '(O)sangūji', 'Sa(n)goji', 'Saguji', 'Shagottsan', 'Shagottan', 'Jogu-san', 'Osangū-san', 'Oshamotsu-sama', or 'Oshamoji-sama' - with different ways of writing them in kanji - are found.[1][9]

The name's etymology is uncertain. During the early modern period when the Mishaguji were conflated with the divine children (mikogami) of Takeminakata, the god of the Upper Suwa Shrine, the name was explained as being derived from the term sakuchi (闢地, lit. 'to open up / develop the land'), which in turn was connected with legends that credit Takeminakata's offspring with forming and developing the land of Shinano.[10][11] The name has also been interpreted as deriving from shakujin / ishigami (石神 'stone deity'), a term used for sacred stones or rocks that were worshiped as repositories (shintai) of kami (it has been observed that stones or stone items were employed as shintai in many Mishaguji-related shrines), or shakujin (尺神), due to another association with bamboo poles and measuring ropes used in land surveying and boundary marking.[7][12] The term sakujin (作神 'harvest / crop deity') has also been suggested as a possible origin.[13] Ōwa Iwao (1990) meanwhile theorized the name to be derived from (mi)sakuchi (honorific prefix 御 mi- + 作霊, 咲霊 sakuchi), a spirit (chi; cf. ikazu-chi, oro-chi, mizu-chi) that brings forth or opens up (saku, cf. 咲く 'to bloom', 裂く 'to tear open', 作 'to do/make/cultivate/grow';cf. also the verb sakuru/shakuru 'to dig/scoop up'[14][15][16]) the latent life force present in the soil or the female womb.[17][18]

Extent of cult

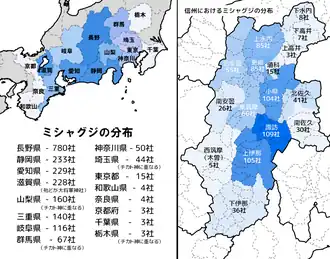

Research conducted by local amateur historian Nogiku Imai in the 1950s revealed a total of over 750 '(Mi)s(h)aguji' shrines within Nagano Prefecture, 109 of which are in the Suwa area (comprising the modern municipalities of Chino, Suwa, Okaya, Shimosuwa, Fujimi, and Hara).[19][20]

As noted above, worship of kami with names such as 'S(h)aguji' or 'S(h)agoji' are also attested in neighboring areas, being notably widespread throughout the Kantō and Chūbu regions of Japan. Shrines enshrining these gods are found in places such as Shizuoka (233 shrines), Aichi (229 shrines), Yamanashi (160 shrines), Mie (140 shrines) and Gifu (116 shrines).[21][22] On the other hand, such shrines are conspicuously absent in the two prefectures of Niigata and Toyama, located to the north of Nagano.[21]

Imai expanded upon the initial research carried out by folklorist Kunio Yanagita, who noted that the worship of 'Shaguji' is distinctive to eastern Japan. In his 1934 work "Place Names and History" (地名と歴史), Yanagita commented:

Although the worship of Kōjin, mountain deities (山神, yama no kami), earth deities (地ノ神, chi no kami), and Dōsojin are also found in western areas, the deity called 'Shaguji' (社宮神) is found only to the east of the Ise and Kii regions. Over twenty years ago, I wrote a small book on this [referring to his 1910 book Ishigami Mondō (石神問答, "Dialogue on Ishigami")]. What I have since learned is that this seems to be the remnant of a now-declining belief centered around a local kami originating from the Suwa region in Shinano.[23]

In the preface to the 1935 reprint of Ishigami Mondō, Yanagita wrote further:

Since then, I have gradually come to understand a bit more about the 'Osagujin' (御左口神) of Suwa Shrine in Shinano Province. First and foremost, it has become clear that this was originally a tree deity (木の神, ki no kami), and at least this part can now be said to be definitively established. However, I still cannot explain why this deity's name transformed into such variant forms as 'Shaguji' (社宮司), 'Shagoji' (社護神), or 'Shagunjin' (遮軍神), and why it spread only in the Chūbu region and its neighboring areas. Even if the hypothesis that Suwa is the cultic point of origin is tentatively correct, I still cannot at all explain, even after thirty ears, why only this specific element of the belief appears to have detached itself and spread across various places.[24]

Imai likewise worked on the assumption that these folk deities and shrines bearing similar names are ultimately derived from Suwa. She suggested the following possibility for the belief's dissemination:

Misakuji (御作神) are found along the main routes of the Tōkaidō and Tōsandō, as well as their branch roads, byways and side paths - linking seacoast to mountain, mountain to plain, plain to pass, and pass to valley, skillfully connecting mountains and rivers. These paths connected pioneer settlements that once grew at key spots blessed by nature along this ancient route, of which traces now remain. These roads served as the ideal route for our ancestors to transport salt and exchange goods.[25]

Imai's view became influential, leading to the widespread classification of all 'Shaguji'/'Shagoji' deities and shrines under a single category known as 'Mishaguji belief' (ミシャグジ信仰, Mishaguji shinkō). However, more recent scholarship has challenged the notion that all "Mishaguji-like" deities and shrines across Japan stem from the Suwa region, arguing for a more nuanced categorization. Hotaka Ishino (2018) proposed that the Mishaguji featured in Suwa Shrine rituals, along with derivative or disconnected forms that may have roots in Suwa but have evolved independently, as well as local beliefs elsewhere that only superficially resemble Mishaguji worship, should all be distinguished and analyzed separately. He emphasizes that, in the original Suwa context, only certain individuals had the authority to perform Mishaguji-related rituals. Therefore, any evidence of ishigami worship in areas where these priests would unlikely have traveled is probably unrelated to Suwa's Mishaguji.[26]

In Suwa Shrine's practice and belief

Suwa Taisha consists of four main shrines grouped into two sites: the Upper Shrine (Kamisha), located southwest of Lake Suwa, and the Lower Shrine (Shimosha), located on the northwesern side of the lake. Historically, the Upper and the Lower Shrines were two separate entities, each with its own priestly hierarchy and religious ceremonies. The two shrines were each formerly headed by a priest known as the Ōhōri (大祝); the Upper Shrine's Ōhōri was unique in that he was regarded upon assuming office as a go-shintai, the physical embodiment of the shrine's deity (Takeminakata or Suwa Daimyōjin), and was thus worshiped as a living god (arahitogami). Second to the Upper Shrine's Ōhōri was the Kan-no-Osa / Jinchō (神長) or Jinchōkan (神長官), the main priest responsible for overseeing and conducting the Upper Shrine's religious ceremonies, including the investiture ceremony of the Ōhōri. It was the Jinchō who had the sole prerogative of summoning and dismissing the Mishaguji in rites that call for their presence.[27]

The relation between the Ōhōri and the Jinchō is explained in mythic terms by the story of Suwa Daimyōjin establishing his presence in Suwa by subjugating the local deity Moriya (also known as Moreya), who formerly controlled the region. After his defeat, Moriya became a subordinate to Suwa Daimyōjin. The Jinchō's clan, the Moriya, is said to be descendants of Moriya, while the Ōhōri's clan, the Suwa, is said to be descended from Suwa Daimyōjin.[28][29]

Function

Mishaguji are believed to be spirits that dwell in rocks, trees, or bamboo leaves,[4][30][31] as well as various man-made objects such as phallic stone rods (石棒 sekibō),[32][33][34] grinding slabs (石皿 ishizara) or mortars (石臼 ishiusu).[35][20] In addition to the above, Mishaguji are also thought to descend upon straw effigies[36] as well as possess human beings, especially during religious rituals.[35][31]

This concept of Mishaguji as a possessing spirit are reflected in texts that describe Mishaguji being 'brought down' (降申 oroshi-mōsu, i.e. being summoned into a repository, whether human or object) or 'lifted up' (上申 age-mōsu, i.e. being dismissed from its vessel) by the Moriya jinchōkan, the priest with the exclusive right to call upon Mishaguji in the religious rites of the Suwa Grand Shrine.[37]

Folk beliefs considered Mishaguji to be associated with fertility and the harvest,[20] as well as healers of diseases like the common cold or pertussis.[38][39] Mishaguji have been worshipped as tutelary deities of whole villages (産土神 ubusuna-gami) as well as specific kinship groups (祝神 iwai-gami).[40] Further reflecting this relationship between Mishaguji and local communities is their being believed to preside over the act of founding villages[39] as well as their being associated with the broadly similar concept of saikami (patrons of boundaries or borders).[41]

See also

- Animism

- Baetylus

- Great Spirit

- Holy Spirit

- Mana

- Moreya

- Snake worship

- Suwa clan

- Suwa-taisha

- Takeminakata

- Touhou Project

Notes

References

- ^ a b Imai, Nogiku (2017). "Mishaguji no tōsa shūsei (御社宮司の踏査集成)". In Kobuzoku Kenkyūkai (ed.). Kodai Suwa to Mishaguji saiseitai no kenkyū (古代諏訪とミシャグジ祭政体の研究). Ningen-sha. pp. 212–281.

- ^ Yamamoto, Kenichi (2010). "Mishakuji: taiko kara no seimei no tsuranari (ミシャクジ-太古からの生命のつらなり)". Collected Papers on Japanese Culture at Teikyō University (帝京日本文化論集) (17): 255–271.

- ^ Oh, Amana ChungHae (2011). Cosmogonical Worldview of Jomon Pottery. Sankeisha. pp. 156–159. ISBN 978-4-88361-924-5.

- ^ a b Moriya, Sanae (1991). Moriya Jinchōke no ohanashi (守矢神長家のお話し). In Jinchōkan Moriya Historical Museum (Ed.). Jinchōkan Moriya Shiryōkan no shiori (神長官守矢資料館のしおり) (Rev. ed.). p. 4.

- ^ Ōwa, Iwao (1990). Shinano Kodai Shikō (信濃古代史考). Tokyo: Meicho Shuppan. pp. 212–214. ISBN 978-4626013637.

- ^ Ōwa (1990). p. 189.

- ^ a b Miyasaka (1987). p. 24.

- ^ Hosoda, Kisuke (2003). Kenpō Moriya bunsho o yomu: chūsei no shijitsu to rekishi ga mieru (県宝守矢文書を読む―中世の史実と歴史が見える). Hoozuki Shoseki. pp. 55–56.

- ^ Yanagita, Kunio (1910). Ishigami mondō (石神問答). Tokyo: Juseidō (聚精堂). pp. 2ff.

- ^ Yamada, Hajime (1929). Suwa Daimyōjin (諏訪大明神). Shinano Kyōdo Sōsho (信濃郷土叢書), vol. 1. Shinano Kyōdo Bunka Fukyūkai (信濃郷土文化普及協会). pp. 135–136.

- ^ Miwa, Iwane (1978). Suwa Taisha (諏訪大社). Gakuseisha. p. 31.

- ^ Ōwa (1990). pp. 189-191.

- ^ Imai, Nogiku (2017). "Misakujin (御作神)". In Kobuzoku Kenkyūkai (ed.). Kodai Suwa to Mishaguji saiseitai no kenkyū (古代諏訪とミシャグジ祭政体の研究). Ningen-sha. pp. 181–189.

- ^ "'sakuru' (さく・る)". goo Jisho (goo辞書).

- ^ "'sakuru', 'shakuru' (さく・る、しゃく・る)". Weblio Jisho (Weblio辞書).

- ^ Tanaka, Atsuko (2011). "古社叢の「聖地」の構造(3)─諏訪大社の場合 (The Sacred Site Structure of Ancient Shrine Groves (3) Primitive Beliefs in Suwa)" (PDF). Journal of Kyoto Seika University: 130.

- ^ Ōwa (1990). pp. 192-194.

- ^ Oh (2011). p. 178.

- ^ Miyasaka (1987). p. 24.

- ^ a b c Oh (2011). p. 164.

- ^ a b Ōwa (1990). p. 199.

- ^ Tanaka (2011). p. 128.

- ^ Yanagita, Kunio (1970). "Chimei to rekishi (地名と歴史)". 定本 柳田国男集 第20巻. Chikuma Shobō. p. 65.

- ^ Yanagita, Kunio (1969). "Ishigami mondō (石神問答)". 定本 柳田国男集 第12巻. Chikuma Shobō. p. 3.

- ^ Imai, Nogiku (2017). "Misakuji (御作神))". In Kobuzoku Kenkyūkai (ed.). Kodai Suwa to Mishaguji saiseitai no kenkyū (古代諏訪とミシャグジ祭政体の研究). Ningen-sha. pp. 187–188.

- ^ Ishino, Hotaka (2018). "石神信仰と草薙剣". Suwa-Animism, vol. 4 (スワニミズム 第4号). pp. 46–47.

- ^ Suwa Shishi Hensan Iinkai, ed. (1995). 諏訪市史 上巻 原始・古代・中世 (Suwa-shi Shi (History of Suwa City), vol. 1: Genshi, Kodai, Chūsei) (in Japanese). Suwa. pp. 726–727.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Moriya, Sanae (1991). Moriya Jinchōke no ohanashi (守矢神長家のお話し). In Jinchōkan Moriya Historical Museum (Ed.). Jinchōkan Moriya Shiryōkan no shiori (神長官守矢資料館のしおり) (Rev. ed.). pp. 2–3.

- ^ Miyasaka, Mitsuaki (1992). 諏訪大社の御柱と年中行事 (Suwa-taisha no Onbashira to nenchu-gyōji). Kyōdo shuppansha. pp. 88–93. ISBN 978-4-87663-178-0.

- ^ Miyasaka (1987). p. 27.

- ^ a b Tanigawa (1987). p. 185, 193.

- ^ Louis-Frédéric (2002). Japan Encyclopedia. Translated by Roth, Käthe. Harvard University Press. p. 838. ISBN 978-0674017535.

- ^ Ouwehand, Cornells (1964). Namazu-e and Their Themes: An Interpretative Approach to Some Aspects of Japanese Folk Religion. Leiden: E. J. Brill. p. 197.

- ^ "Sekibō worship in the Jōmon Period (縄文時代の石棒祭祀 Jōmon-jidai no sekibō-saishi)". Suwa City Museum (諏訪市博物館).

- ^ a b Ōwa (1990). p. 191.

- ^ Tanigawa (1987). pp. 180-181.

- ^ Miyasaka (1987). p. 26.

- ^ Fukuta, Ajio; et al., eds. (1999). 日本民俗大辞典〈上〉あ〜そ (Nihon Minzoku Daijiten, vol. 1: A - So). Tokyo: Yoshikawa Kōbunkan. p. 802. ISBN 978-4642013321.

- ^ a b Miyasaka (1987). p. 25.

- ^ Miyasaka (1987). p. 23.

- ^ Gotō, Sōichirō, ed. (1996). 'Tōno Monogatari' kenkyu sōkō (『遠野物語』研究草稿). Meiji University School of Political Science and Economics. p. 20.

Bibliography

- Jinchōkan Moriya Historical Museum, ed. (1991). 神長官守矢資料館のしおり (Jinchōkan Moriya Shiryōkan no shiori) (in Japanese) (Rev. ed.). Chino.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Oh, Amana ChungHae (2011). Cosmogonical Worldview of Jomon Pottery. Sankeisha. ISBN 978-4-88361-924-5.

- Ōwa, Iwao (1990). 信濃古代史考 (Shinano Kodai Shikō) (in Japanese). Tokyo: Meicho Shuppan. ISBN 978-4626013637.

- Suwa Shishi Hensan Iinkai, ed. (1995). 諏訪市史 上巻 原始・古代・中世 (Suwa-shi Shi (History of Suwa City), vol. 1: Genshi, Kodai, Chūsei) (in Japanese). Suwa.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Tanigawa, Kenichi, ed. (1987). 日本の神々―神社と聖地〈9〉美濃・飛騨・信濃 (Nihon no kamigami: Jinja to seichi, vol. 9: Mino, Hida, Shinano) (in Japanese). Hakusuisha. ISBN 978-4-560-02509-3.

- Ueda, Masaaki; Gorai, Shigeru; Miyasaka, Yūshō; Ōbayashi, Taryō; Miyasaka, Mitsuaki (1987). 御柱祭と諏訪大社 (Onbashira-sai to Suwa-taisha) (in Japanese). Nagano: Chikuma Shobō. ISBN 978-4-480-84181-0.

- Yanagita, Kunio (1910). 石神問答 (Ishigami mondō) (in Japanese). Tokyo: Juseidō (聚精堂). pp. 2ff.