Military of historic Sarawak

| Military of historic Sarawak | |

|---|---|

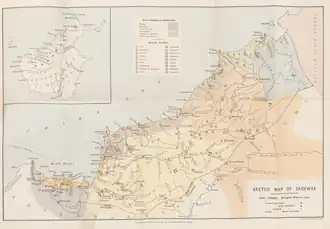

Sketch Map of Sarawak in 1908 | |

| Active | 1599–1946 |

| Disbanded | 1946 |

| Country | Datuan of Sarawak |

| Allegiance | Datu Patinggi Ali |

| Type | army |

| Role |

|

| Size | Unknown |

| Motto(s) | Dum Spiro Spero (While I breathe, I hope) |

| Colours | Yellow |

| Equipment | Many primarily Parang |

| Engagements | None Datuan of Sarawak: Sarawak Uprising of 1836 Anglo-Bruneian War World War II |

| Commanders | |

| Commander | Datu Patinggi Ali |

| Notable commanders | Sultan Tengah Datu Patinggi Ali James Brooke |

| History of Malaysia |

|---|

_(cropped).jpg) |

|

|

| This article is part of a series on the |

| History of Brunei |

|---|

|

The term "Military of historic Sarawak" is a wide term to refer to Sarawak between 1599–1946.

History

Sultanate of Sarawak (1599–1641)

Sultan Tengah constructed a fortified palace in Sungai Bedil, Santubong in 1599,[1] turning the area into the royal, judicial and administrate capital of the kingdom. There were no wars during the reign of Sultan Tengah nor during the entire existence of the Sultanate.

Datuan of Sarawak (1836–1840)

Following 10 years of hardship as a slave worker, Ali rallied his supporters from Siniawan to oppose Pengiran Indera Mahkota. They began to resist in 1836. Datu Bandar, Datu Amar, and Datu Temenggong helped Ali. Patinggi Ali, one of Datu's disciples, first constructed defense fortifications in Siniawan, Lidah Tanah, and other locations—an additional location upstream Bau. They aimed to remove the Bruneian governor and liberate Sarawak from the Sultanate of Brunei's rule. In addition to setting up battle plans, he offered them encouragement and counsel. They put up a fierce fight with Pengiran Indera Makkota. They were still unable to vanquish Pengiran Indera Mahkota despite several battles. Similarly, Ali was defeated by Pengiran Indera Mahkota as well.[2]

This conflict persisted and worsened in 1838 and into 1839. Ali received assistance, as the Sambas Sultan had pledged.[3] Additionally, there was material indicating that the Dutch had prepared to assist the people of the Bau area in defeating the Pengiran Indera Mahkota.[4] Pengiran Muda Hashim understood how tough it would be to overcome Ali's troops. James Brooke, an English traveler in Kuching at the time, was approached for assistance.[5] Brooke and a few other Royalist crew members sailed up the Sarawak River to Siniawan in 1840.[6] The ship was outfitted with contemporary weaponry. There were several conflicts and occasionally discussions with Ali. At last, Brooke was said to have defeated his army at the Lidah Tanah citadel with 600 part-time troops who were Iban, Malay, and Chinese.[2]

The scarcity of food supplies at the time forced Ali's supporters to flee, and many of them—particularly the Bidayuh people—starved to death. The fact that Datu Patinggi Abdul Gapur and Datu Tumanggong Mersal fled to Sambas and Datu Patinggi Ali sought safety in Sarikei after Brooke put an end to the uprising demonstrated the Sultanate of Sambas' sympathy for the rebels.[3] By late 1840, Datu Patinggi Ali had promised to terminate the conflict, but only if Pengiran Indera Mahkota and his family left Kuching. They were spared along with him and his supporters. The conflict with Pengiran Indera Mahkota ended with the aforesaid arrangement. In the end, he and his supporters were able to drive Pengiran Indera Mahkota and his family from Sarawak.[2] At Belidah in December 1840, he submitted, knowing that Brooke would go on to rule an independent Sarawak, with the idea that Brooke would take over the role of Raja and put an end to his oppression by the Brunei Pengirans.[7]

Kingdom of Sarawak (1841–1946)

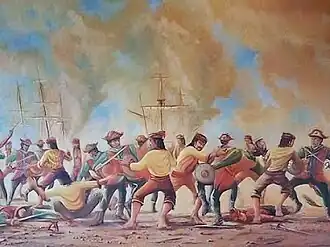

In August 1845, Rear-Admiral Thomas Cochrane arrived at Brunei with a squadron of from six to eight ships to release two Lascar seamen who were believed to be hidden there.[8][9] Badruddin accused Yusof of being involved in the slave trade due to his close relations with a notable pirate leader –Sharif Usman– in Marudu Bay and the Sultanate of Sulu.[8] Denying the allegation, Yusof refused to attend a meeting with Cochrane, and escaped after being threatened with force by Cochrane before regaining his own force in Brunei's capital. Cochrane then sailed away to Marudu Bay in pursuit of Usman, while Yusof was defeated by Badruddin.[8][9] Hashim managed to establish a rightful position in Brunei Town to become the next sultan after successfully defeating the pirates led by Yusof who fled to Kimanis in northern Borneo, where he was executed.[10][11] Yusof was the favourite noble to the Sultan and with Hashim's victory, this upset the chances of the son of Sultan Omar Ali Saifuddin II becoming the next leader.[11][12] Mahkota, after his capture in Sarawak in 1844 became the Sultan's adviser in Yusof's absence. He prevailed on the Sultan to order the execution of Hashim,[9] whose presence had become unwelcome to the royal family, especially due to his close ties with Brooke that were favourable to English policy.[13] Beside that, an adventurer named Haji Saman, who was connected to Yusof, played upon the Sultan's fear of Hashim taking his throne.[14]

By the order of the Sultan, Hashim and his brother Badruddin together with their family were assassinated in 1846.[9][13][15] One of Badruddin's slaves, Japar, survived the attack and intercepted HMS Hazard, which brought him to Sarawak to inform Brooke. Enraged by the news, Brooke organised an expedition to avenge Hashim's death with the aid of Cochrane from the Royal Navy with Phlegethon.[14] On 6 July 1846, Sultan Omar Ali Saifuddin II complained through a letter about the discourtesy of HMS Hazard and invited Cochrane to ascend the capital of Brunei with two boats.

HEICS Phlegethon, HMS Spiteful and HMS Royalist then moved up to the river on 8 July where they were fired on from every position with slight damage.[14] Mahkota and the Sultan retreated upriver while most of the population fled upon their arrival at Brunei's capital, leaving the brother of the Sultan's son, Pengiran Muhammad, who was badly wounded and Pengiran Mumin, an opponent of the Sultan's son who despised the decision of his royal family to be involved in conflict with the British.[9][14] The British destroyed the town forts and invited the population to return with no harm to be done to them while the Sultan remained hiding in the jungle. Another expedition was sent to the interior but failed to find the Sultan. Brooke remained in Brunei with Captain Rodney Mundy and HMS Iris along with the Phlegethon and HMS Hazard while the main expedition continued their mission to suppress piracy in northern Borneo.[14]

Upon finding that Haji Saman was living in Membakut and that he was involved in the plotting that caused Hashim's death, HEICS Phlegethon and HMS Iris departed there destroyed Haji Saman's house and captured the town of Membakut although Saman managed to escape.[14] Brooke returned again to Brunei and finally managed to induce the Sultan to return to the capital where the Sultan wrote a letter of apology to Queen Victoria for the killings of Hashim, his brother and their family.[16] Through his confession, the Sultan recognised Brooke's authority over Sarawak and mining rights throughout the territory without requiring him to pay any tribute as well granting the island of Labuan to the British.[16] Brooke departed Brunei and left Mumin in charge together with Mundy to keep the Sultan in line until the British government made a final decision to acquire the island. Following the ratification agreement of the transfer of Labuan to the British, the Sultan also agreed to allow British forces to suppress all piracy along the coast of Borneo.[16]

World War II

Following World War I, the Empire of Japan began to expand their range in Asia and the Pacific.[17] Vyner became aware of the growing threats and began to institute reforms.[18] Under the treaty of protection, Britain was responsible for Sarawak's defence[19] but it could do little, most of its forces having been deployed to the war in Europe against Germany and the Kingdom of Italy. The defence of Sarawak depended on a single Indian infantry battalion –the 2/15 Punjab Regiment– together with the local forces of Sarawak and Brunei.[19] As Sarawak had a significant number of oil refineries in Miri and Lutong, the British feared that these supplies would fall to Japanese control, and thus instructed the infantry to carry out a scorched earth policy.[19][20]

On 16 December 1941, a Japanese navy detachment on Sagiri arrived at Miri from Cam Ranh Bay in French Indochina.[20][21] The Japanese then launched an air attack on Kuching on 19 December, bombing parts of the town's airfield while machine-gunning people in the streets.[22] The attack created panic and sent residents fleeing to rural areas.[23] The Dutch submarine HNLMS K XVI managed to bring down the Japanese from Miri but, with the arrival of the Shirakumo together with other ships, the Japanese secured the town on 24 December.[24] From 7 January 1942, Japanese troops in Sarawak crossed the border of Dutch Borneo and proceeded to neighbouring North Borneo. The 2/15 Punjab Regiment were forced to withdraw to Dutch Borneo and later surrendered on 9 March after most of the Allies had surrendered in Java.[22] A steamship of Sarawak –the SS Vyner Brooke– was sunk while evacuating nurses and wounded servicemen in the aftermath of the fall of Singapore. Most of its surviving crew were massacred on Bangka Island.[25]

Lacking air protection, Sarawak, together with rest of the island, fell to the Japanese and Vyner took sanctuary in Australia.[26] Many of the British and Australian soldiers captured after the fall of Malaya and Singapore were brought to Borneo and held as prisoners of war in Batu Lintang camp in Sarawak and Sandakan camp in North Borneo. The Japanese military authorities placed the southern part of Borneo under the navy, while its army were responsible for management of the north.[27] As part of the Allied Campaign to retake their possessions in the East, Allied forces were sent to Borneo in the Borneo Campaign and liberated the island. The Australian Imperial Force (AIF) played a significant role in the mission. The Allies' Z Special Unit provided intelligence gathering which facilitated the AIF landings. Most of the major towns of Sarawak were bombed during this period.[23] The war ended on 15 August 1945 following the Japanese surrender and the administration of Sarawak was undertaken by the British Military Administration from September. Vyner returned to administer Sarawak but decided to cede it to the British government as a Crown colony on 1 July 1946 due to a lack of resources to finance reconstruction.[28][29][30]

Organisation

Sultanate of Sarawak (1599–1641)

Sultan Tengah was accompanied by more than 1,000 soldiers from the Sakai, Kedayan, and Bunut tribes, all of whom are natives of Borneo, to Sarawak. A coterie of Bruneian nobility also followed him there.[31][32] Sultan Tengah constructed a fortified palace in Sungai Bedil, Santubong in 1599.[33]

Datuan of Sarawak (1836–1840)

Datu Patinggi Ali's army was made up of rebelling formerly enslaved Sarawakian Malays and Bidayuh alongside armies of rebelling chiefs who used the same Pendekar like Brunei. Ali also received support from the Sambas Sultanate and the Dutch East Indies.[34][35]

Kingdom of Sarawak (1841–1946)

At least 24 forts were built throughout Sarawak during the Brooke era, which were primarily used as administrative centres and centres for defence.[36]

The government worked to restore peace where piracy and tribal feuds had grown rampant and its success depended ultimately on the co-operation of the native village headmen, while the Native Officers acted as a bridge.[37] The Sarawak Rangers was established in 1862 as a para-military force of the raj.[38] It was superseded by the Sarawak Constabulary in 1932 as a police force,[39] with 900 members mainly comprising Dayaks and Malays.[40] Who would fight in World War II.

-

A line-up of armed Sarawak Rangers.

A line-up of armed Sarawak Rangers. -

The Dayaks, who subsequently became Brooke followers and most loyal to the raj along with the local Malays of Sarawak.

The Dayaks, who subsequently became Brooke followers and most loyal to the raj along with the local Malays of Sarawak.

See also

References

- ^ Ritchie, James (11 August 2023). "Darul Hana making a great Sarawak Empire". New Sarawak Tribune. Archived from the original on 10 August 2023. Retrieved 19 December 2023.

- ^ a b c Lawrence Law (2020). PERANG MENENTANG KESULTANAN BRUNEI DI BAU PADA ABAD KE-19 (PDF) (in Malay). Institut Pendidikan Guru Kampus Batu Lintang.

- ^ a b JOANNA YAP (3 April 2016). "Tracing influence of Brunei and Sambas in formation of S'wak". www.theborneopost.com. Retrieved 5 January 2024.

- ^ Pat Foh Chang (1997). Heroes of the Land of Hornbill. Chang Pat Foh. ISBN 978-983-9475-04-3.

- ^ Pat Foh Chang (1995). The Land of Freedom Fighters. Ministry of Social Development.

- ^ William L. S. Barrett (1988). Brunei and Nusantara History in Coinage. Brunei History Centre. p. 229.

- ^ "A portrait of Datu Patinggi Ali". www.brooketrust.org. 13 April 2016. Retrieved 5 January 2024.

- ^ a b c Saunders 2013, p. 76.

- ^ a b c d e Gott 2011, p. 374.

- ^ Miller 1970, p. 95.

- ^ a b Royal Asiatic Society 1960, p. 292.

- ^ Mills 1966, p. 258.

- ^ a b Miller 1970, p. 94.

- ^ a b c d e f Saunders 2013, p. 77.

- ^ Sidhu 2016, p. 154.

- ^ a b c Saunders 2013, p. 78.

- ^ Ooi 1999, p. 1.

- ^ Shepley 2015, p. 46.

- ^ a b c Kratoska 2013, p. 136.

- ^ a b Rottman 2002, p. 206.

- ^ Williams 1999, p. 6.

- ^ a b Tarling 2001, p. 91.

- ^ a b Tan 2011.

- ^ Jackson 2006, p. 440.

- ^ Pateman 2017, p. 42.

- ^ Bayly & Harper 2005, p. 217.

- ^ Ooi 2013, p. 15.

- ^ Yust 1947, p. 382.

- ^ Lockard 2009, p. 102.

- ^ Sarawak State Government 2014.

- ^ Sarawak State Secretary Office 2016

- ^ Gregory 2015

- ^ Ritchie, James (11 August 2023). "Darul Hana making a great Sarawak Empire". New Sarawak Tribune. Archived from the original on 10 August 2023. Retrieved 19 December 2023.

- ^ JOANNA YAP (3 April 2016). "Tracing influence of Brunei and Sambas in formation of S'wak". www.theborneopost.com. Retrieved 5 January 2024.

- ^ Pat Foh Chang (1997). Heroes of the Land of Hornbill. Chang Pat Foh. ISBN 978-983-9475-04-3.

- ^ "A Walk Through Forts in Sarawak". Sarawak Museum Department. Archived from the original on 2 December 2024. Retrieved 13 April 2025.

- ^ Talib 1999, p. 47.

- ^ Tarling 2003, p. 319.

- ^ Ellinwood & Enloe 1978, p. 201.

- ^ Epstein 2016, p. 102.