Miki Hayakawa

Miki Hayakawa | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | June 7, 1899 |

| Died | March 6, 1953 (aged 53) |

| Occupation | Visual Artist |

| Movement | California Modernism |

| Spouse | Preston McCrossen (1947-1953) |

Miki Hayakawa (June 7, 1899 – March 6, 1953) was a Japanese-born American modernist painter known for her keen observation, treatment of color, and use of pattern and space in portraiture and landscape. She was a leading woman artist within the vibrant multi-ethnic and multicultural art community in the San Francisco Bay Area beginning in 1920 until the early months of World War II when she relocated to Santa Fe, New Mexico to avoid incarceration under Executive Order 9066. There Hayakawa became part of the art establishment in Santa Fe and continued to grow her career as a painter until her early death in 1953.[1][2]

Early life and education

Miki Hayakawa was born in Nemuro, on the Japanese island of Hokkaido in 1899. She was the only child of Man and Chiyo Hayakawa. In 1908, she immigrated with her mother to the United States, joining her father who had arrived a year earlier. Her family settled in Alameda, California, home to a thriving Japanese community located across the bay from San Francisco.[3][4]

In 1917 at the age of 18, Hayakawa married Kiyoshi Okuye, a Japanese farmer from the Central Valley community of Livingston. The marriage was probably arranged by her parents in keeping with traditional cultural expectations within the Japanese community. Hayakawa defied custom by leaving the marriage and seeking her own path in life. She was determined to become an artist.[3]

With the aid of a scholarship, Hayakawa began her formal study of art at the California School of Arts and Crafts in Berkeley in 1922. The next year she enrolled in the California School of Fine Arts, which was known for its progressive atmosphere, intellectual rigor, and diverse student body. There she encountered advocates of European and American modernism which influenced the development of her painting style and use of color.[3][5]

Career as an artist in California

As one of the premier art schools in the West, the California School of Fine Arts attracted leading modernist artists to its faculty including Otis Oldfield and Ralph Stackpole. Women artists such as Constance Jenkins Macky and Gertrude Partington Albright were also prominent teachers. The school cultivated an optimistic and innovative environment that shaped the Bay Area art scene, and enabled young artists like Hayakawa to develop technical expertise, a unique artistic vision, and important social connections.[3] During her study at the California School of Fine Arts, Hayakawa became close friends with students Yun Gee, Matsusaburo Hibi, and Hisako Shimizu (later Hibi).[5]

Hayakawa started gaining critical attention in 1925 when she was recognized with the top award in the portrait painting class at the California School of Fine Arts and showed two paintings in the annual exhibition of the San Francisco Art Association. In 1927, out of 900 students, Hayakawa became the first student in the school's history to win both the Virgil Williams and Anne Bremer scholarships at the California School of Fine Arts.[1][6]

Her first solo exhibition took place in 1929 at the Golden Gate Institute (Kinmon Gakuen), the center of Japanese artistic and culture in San Francisco. The exhibition featured 150 major paintings encompassing figurative nudes, landscape, and still life subjects. Critics enthusiastically responded to the exhibition validating the interest given to her work in previous years. Reviewers commented on her keen observation, mastery of craft, and productive capacity.[7]

Throughout the 1920s and 1930s, Hayakawa consistently exhibited with various local groups in the San Francisco Bay Area. In 1927 and 1928 she was the only Japanese woman artist shown in the San Francisco Art Association’s annual exhibition. She was also the only Japanese woman artist included in the inaugural exhibition of the San Francisco Museum of Art (now the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art) at the Civic Center in 1935.[8] After the success of her solo exhibition in 1929, Hayakawa started showing her work outside of the San Francisco Bay Area, participating in the Painters and Sculptors of Southern California annual exhibitions at the Los Angeles Museum (1927, 1936, 1937) and the 1934 Oriental Art Exhibit at the Foundation of Western Art in Los Angeles.[9] To sustain her livelihood as an artist, Hayakawa also worked as a caterer.[1]

Appearing in the Golden Gate International Exposition of 1939-1940 was a high point in her career. The exposition not only celebrated the completion of the Golden Gate Bridge and the San Francisco-Oakland Bay Bridge, but like other world fairs, featured an eclectic survey of engineering and technological achievements along with innovative architecture and art. The exposition had a space dedicated to California artists, and it was significant that Hayakawa, along with her fellow Japanese American artists Hisako Hibi, Chiura Obata, and Henry Sugimoto, who by law were ineligible for citizenship, were defined as American artists at an international event taking place just before World War II.[10]

Career in New Mexico

Hayakawa resided outside of the San Francisco Bay Area in the late 1930s. Records indicate time in Pacific Grove, Monterrey, and Stockton. Sometime following the bombing of Pearl Harbor in December 1941 and subsequent Executive Order 9066 in February 1942, Hayakawa voluntarily relocated to Santa Fe, New Mexico to avoid incarceration with Japanese Americans residing on the West Coast of the United States.[11] Her parents were sent to the Tanforan Assembly Center and later moved to the Topaz War Relocation Center in Utah.[5]

Hayakawa became an active member of the Santa Fe art community, adopting elements from her new environment into her portraits and landscapes.[5] She exhibited her work locally while continuing to maintain her professional relationships in San Francisco. In 1944, the Museum of New Mexico presented a solo retrospective exhibition of her work.

In Santa Fe, she connected with painter Preston McCrossen, whom she may have known previously when he worked in the San Francisco Bay Area in the late 1920s. Hayakawa married McCrossen in 1947. People acquainted with her in Santa Fe remember Hayakawa as “warm, vivacious” and “an excellent artist and an excellent cook.” She was known for welcoming new artists into the community and organizing weekly sketching classes.[12]

Hayakawa died in Santa Fe on March 6, 1953, at the age of 53. McCrossen donated one of Hayakawa’s best-known paintings, One Afternoon (1935), to the New Mexico Museum of Art. A second painting, Untitled (Seated Female Nude), from her first solo exhibition in 1929, was donated to the museum in 1986.[13][14]

Legacy

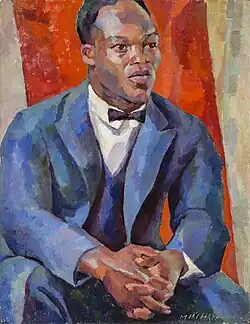

After her death, most of Hayakawa's paintings entered private collections and the artist was largely forgotten.[15] Interest in Hayakawa’s work resurged when the Los Angeles County Museum of Art included her painting Portrait of a Negro (ca. 1926)[16] in Art Everywhere US campaign online in 2014. The painting had also been shown in LACMA’s traveling exhibition to Australia America: Painting a Nation the year before as an example of multicultural American modernism.[17]

Art historian ShiPu Wang traced Hayakawa’s life history and identified the location of a significant number of her paintings. He published his research in 2017 in the book The Other American Moderns: Matsura, Ishigaki, Noda, Hayakawa. Wang also featured Hayakawa’s work in the 2024 exhibition and publication Pictures of Belonging: Miki Hayakawa, Hisako Hibi, and Miné Okubo in collaboration with the Japanese American National Museum. The exhibition will be on view at five museums in the United States including the Utah Museum of Fine Arts, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Monterey Museum of Art, and the Japanese American National Museum in 2024-2026.[18]

Museums with paintings by Hayakawa

Scholarship

Wang, ShiPu. Pictures of Belonging: Miki Hayakawa, Hisako Hibi, and Miné Okubo. University of California Press, 2023. ISBN: 9780520394674

___. The Other American Moderns: Matsura, Ishigaki, Noda, Hayakawa. Penn State University Press, 2017. ISBN: 9780271077734

References

- ^ a b c Wang, ShiPu; Japanese American National Museum (Los Angeles, Calif.), eds. (2023). Pictures of belonging: Miki Hayakawa, Hisako Hibi, and Miné Okubo. Los Angeles: Japanese American National Museum. pp. 11–15. ISBN 978-0-520-39467-4.

- ^ Shinn, Masako Hashigami (November 21, 2024). "Miki Hayakawa: A Life and Legacy of Art and Resilience, Part 2". Discover Nikkei. Retrieved 1 Aug 2025.

- ^ a b c d Shinn, Masako Hashigami (November 29, 2024). "Miki Hayakawa: A Life and Legacy of Art and Resilience, Part 1". Discover Nikkei. Retrieved 1 Aug 2025.

- ^ "Miki Hayakawa: Painting in Place | The Huntington". huntington.org. Retrieved 2024-03-27.

- ^ a b c d "Miki Hayakawa". Densho Encyclopedia. February 12, 2024. Retrieved March 27, 2024.

- ^ Wang, ShiPu (2017). The Other American Moderns: Matsura, Ishigaki, Noda, Hayakawa. University Park, PA: Penn State University Press. p. 99. ISBN 9780271080727.

- ^ Wang. The Other American Moderns. pp. 109–112.

- ^ Wang. The Other American Moderns. p. 107.

- ^ Wang. The Other American Moderns. p. 113.

- ^ Wang (2021). The Other American Moderns. pp. 120–121.

- ^ Kovinick, Phil; Yoshiki-Kovinick, Marian (1999). An encyclopedia of women artists of the American West. American studies series (1. ed., 3. pr ed.). Austin: University of Texas Press. p. 132. ISBN 978-0-292-79063-6.

- ^ Wang. The Other American Moderns. pp. 122–26.

- ^ Hayakawa, Miki (1935). "One Afternoon". New Mexico Museum of Art. Retrieved 31 July 2025.

- ^ Hayakawa, Miki (1928). "Untitled (Seated Female Nude)". New Mexico Museum of Art. Retrieved 31 July 2025.

- ^ Carballo, Rebecca (April 5, 2024). "Women Who Made Art in Japanese Internment Camps Are Getting Their Due". The New York Times. Retrieved 1 Aug 2025.

- ^ "Portrait of a Negro | LACMA Collections". collections.lacma.org. Retrieved 2025-08-05.

- ^ Wang. The Other American Moderns. p. 97.

- ^ "Wang Curates New Traveling Exhibition of Three Trailblazing Japanese American Women | Staff and Faculty of Color Association". sfca.ucmerced.edu. Retrieved 2025-08-05.

External links

- Pictures of Belonging: Miki Hayakawa, Hisako Hibi, and Miné Okubo at the Smithsonian American Art Museum, November 15, 2024-August 17, 2025.