Miguel Ángel Mancera

Miguel Ángel Mancera | |

|---|---|

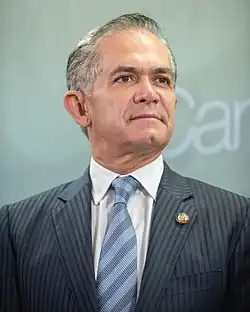

Mancera in 2022 | |

| Senator of the Republic (proportional representation) | |

| In office 1 September 2018 – 31 August 2024 | |

| 6th head of government of Mexico City | |

| In office 5 December 2012 – 29 March 2018 | |

| Preceded by | Marcelo Ebrard |

| Succeeded by | José Ramón Amieva (acting) |

| National Conference of Governors | |

| In office 3 May 2017 – 13 December 2017 | |

| Preceded by | Graco Ramírez |

| Succeeded by | Arturo Núñez Jiménez |

| Attorney General of Justice of Mexico City | |

| In office 8 July 2008 – 6 January 2012 | |

| Governor | Marcelo Ebrard |

| Preceded by | Rodolfo Félix Cárdenas |

| Succeeded by | Jesús Rodríguez Almeida |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Miguel Ángel Mancera Espinosa 16 January 1966 Miguel Hidalgo, Mexico City, Mexico |

| Political party | Independent[a] |

| Children | 3 |

| Residence(s) | Mexico City, Mexico |

| Alma mater | National Autonomous University of Mexico |

Miguel Ángel Mancera Espinosa (Spanish pronunciation: [miˌɣeˈlaŋxel manˈseɾa]; born 16 January 1966) is a Mexican lawyer and politician who works with the Party of the Democratic Revolution (PRD).[a] He served as the head of government of Mexico City from 2012 to 2018.

Mancera earned his law degree from the Faculty of Law at the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM) in 1989 and received the Gabino Barreda Medal in 1991 for academic excellence. He holds a master's degree from both the University of Barcelona and the Metropolitan Autonomous University, as well as a Juris Doctor from UNAM. Mancera has taught at several universities, including the UNAM, the Autonomous Technological Institute of Mexico and the University of the Valley of Mexico.

In 2002, he began working in public service when Marcelo Ebrard, then Secretary of Public Security of Mexico City, invited him to serve as an adviser. In 2006, Mancera was appointed Assistant Attorney General, and from 2008 to 2012, he served as the city's Attorney General. In early 2012, Mancera was selected as the candidate for Head of Government of the Federal District by the Progressive Movement coalition, which included the PRD, the Labor Party, and the Citizens' Movement. In the election held on 1 July 2012, he won with over 66 percent of the vote.

He took office on 5 December 2012. During his mandate, Mancera faced the increase of the Mexico City Metro fare, the first closure of Metro Line 12 due to construction issues, the introduction of the city's constitution, the implementation of new driving regulations, and the 2017 Puebla earthquake. He resigned on 29 March 2018, to run for the Senate, leaving office with the lowest approval rating for a head of government. His administration was scrutinized by his successor, Claudia Sheinbaum, who prosecuted multiple crimes allegedly committed during his tenure. Ultimately, Mancera was sanctioned with a one-year disqualification from holding any public office in the city after promoting a presidential candidate while serving as head of government. He served as proportional-representation senator from 2018 to 2024.

Early life and education

Miguel Ángel Mancera Espinosa was born on 16 January 1966, in the colonia (neighborhood) of Anáhuac,[3] located in the Miguel Hidalgo, borough of the Federal District (later known as Mexico City). His father founded the restaurant chain Bisquets Obregón.[3][4][5] Mancera has four half-siblings.[5] When he was four, he lived in the colonia of Tacuba,[6] where he attended kindergarten.[5] He later studied at Miguel Alemán Primary School and Secondary School No. 45, both located in the Benito Juárez borough.[5][6] For high school, he enrolled at Preparatoria 6, part of the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM).[5][6]

As a teenager, Mancera was involved in a car accident in whicht in which the vehicle he was riding in was hit by another. The public prosecutor's office asked him to sign a document absolving the driver of liability.[5][6] Mancera refused and took the case to Victoria Adato Green, then-Attorney General of the Federal District. With the help of legal advisor Diego Ramudia, he succeeded in having the driver fined.[6] The experience led him to change his career path from a science-related field to law. He studied at the Faculty of Law of the UNAM from 1985 to 1989.[5][6]

His thesis, "La libertad por desvanecimiento de datos en el Proceso Penal y la Absolución de la Instancia" ("The progressive release of public data on criminal prosecutions and acquittals") earned him the Diario de México Medal "Los Mejores Estudiantes de México" in November 1990.[7] A year later, in November 1991, he received the Gabino Barreda Medal from the UNAM Faculty of Law for graduating at the top of his 1989 class.[4][6][7] Mancera went on to earn a master's degree from both the University of Barcelona and the Metropolitan Autonomous University, Azcapotzalco campus,[6][8] and later obtained a Juris Doctor from UNAM, with honors.[9] His doctoral thesis was titled "El injusto en la tentativa y la graduación de su pena en el derecho penal mexicano" ("Injustice and disparity in Mexican criminal sentencing").[6] He also pursued specialized studies in criminal law at the University of Salamanca and the University of Castile-La Mancha, Spain,[9][10][11] under the auspices of the Panamerican University, Mexico.[9][11]

Early political career

Mancera has worked as a candidate attorney, lawyer, and adviser at several law firms, including García Cordero y Asociados and Grupo de Abogados Consultores.[5][12] He has also been a professor at various Mexican universities, including the UNAM, the Autonomous Technological Institute of Mexico, the University of the Valley of Mexico, the Panamerican University, the Autonomous University of Aguascalientes, and the Autonomous University of Baja California.[4][6][9]

In 2002, Mancera served as a member of the review committee for the Criminal Procedure Code for the Federal District.[9] Around the same time, he began working in government when Marcelo Ebrard, then Secretary of Public Security of Mexico City, invited him to serve as an adviser.[1][10] When Ebrard was later appointed Secretary of Social Development by the head of government Andrés Manuel López Obrador, Mancera was named Legal Director of the Social Development Secretariat.[10] In 2006, he was appointed Assistant Attorney General of Mexico City.[10]

Mancera was appointed Attorney General of Mexico City on 8 July 2008, following the dismissal of Rodolfo Félix Cárdenas due to the New's Divine nightclub tragedy,[13][14] in which nine teenagers and three police officers died during a failed police operation.[3][15] According to official reports,[16] crime in Mexico City decreased by 12 percent from 2010 to 2011,[2][3][16] while the national crime rate rose by 10.4 percent.[3] During this period, 179 street gangs comprising 706 members were dismantled,[17] and kidnappings dropped by 61 percent.[18]

Head of government of Mexico City

2012 elections

On 6 January 2012, Mancera resigned as Attorney General to run for Head of Government in the 1 July 2012 election. Jesús Rodríguez Almeida succeeded him in the role.[19] Two days later, on 8 January, Mancera registered as a Party of the Democratic Revolution (PRD) precandidate for head of government of Mexico City.[20] On 19 January, he was named the official candidate, representing the leftist Progressive Movement coalition, which also included the Labor Party, and the Citizen's Movement. He ran against Alejandra Barrales, Gerardo Fernández Noroña, Martí Batres, and Joel Ortega Cuevas.[21][22]

Mancera's opponents were Beatriz Paredes Rangel, representing the Institutional Revolutionary Party–Ecologist Green Party of Mexico coalition Commitment to Mexico; Isabel Miranda de Wallace, for the National Action Party (PAN); and Rosario Guerra for the New Alliance Party.[23] Late-January polls showed Mancera leading Paredes by 18 to 30 points, though his support dropped nine points the following month.[24][25] According to El Universal, his favorability rose from 36 percent in March to 41 percent in April, and to 57.5 percent in May.[26][27] That same month, Adolfo Hellmund, Luis Mandoki, and Costa Bonino allegedly borrowed six million dollars on behalf of Mancera and López Obrador at the home of Luis Creel. Both politicians denied involvement, and Mancera filed a complaint with the Attorney General of Mexico City for unauthorized use of his name.[28][29]

As candidate, the proposals of Mancera included continuing Ebrard's policies,[30] increasing the number of security cameras from 13,000 to 20,000,[31] reducing car travel times, expanding Mexico City Metro Line 12, addressing solid waste management, removing minibuses from circulation, building 18 water purification plants, implementing a Green Plan, and replacing garbage trucks to enable the separation of organic and inorganic waste, among other initiatives.[32] On 1 July 2012, exit polls indicated Mancera as the likely winner of the election, with an estimated vote share of 59.5–64.5 percent,[33] placing him roughly 40 percentage points ahead of the second-place candidate, Paredes.[1] On 7 July, the Federal District Electoral Institute (IEDF) declared Mancera the Head of Government-elect and issued him a certificate of majority after he secured 3,031,156 votes (66.56 percent of the total) in a landslide victory,[34][35][36] which he received on 8 October 2012.[36][37]

First year

Mancera assumed office on 5 December 2012,[38] as the sixth head of government of the Federal District.[39] On 24 December of the same year, he launched a voluntary disarmament campaign in the borough of Iztapalapa. In exchange for turning in firearms and grenades, participants received money, tablet computers, or home appliances.[40][41] The program was later implemented across all Mexico City boroughs in the following years.[42][43][44] City Mayors Foundation named Mancera the mayor of June 2013.[45] In November 2013, Mancera opened Line 5 of the Mexico City Metrobús running along northeastern Mexico City from Río de los Remedios to San Lázaro metro station.[46]

In the same month, Mancera announced the increase of the Mexico City Metro fare, raising the price from three to five pesos per ride. According to the Metro operator, Sistema Transporte Colectivo, the additional revenue would be used to improve infrastructure and maintain the system's twelve lines and its stations.[47] The fare increase drew criticism from parts of the city's population, who viewed it as a strain on household finances, especially given that the minimum wage in Mexico City was 64.76 pesos as of January 2013.[48][49] In response, Mancera stated that three polling companies would conduct surveys with 7,200 Metro riders between 29 November and 2 December to gather public opinion—the sample represented less than one percent of the system's 5.5 million daily users.[50][51] According to polling company results, over 50 percent of respondents supported the fare increase. The new fare was approved to take effect on 13 December.[52] Due to this, through the short-lived Movimiento Pos Me Salto, users called to civil disobedience protests by jumping over the turnstiles.[53][54] However, Mexico City Government announced they would take legal actions against those who skip them.[55][56]

Second year

On 11 March 2014, Mancera's administration closed twelve metro stations on Line 12 of the Metro due to construction-related issues. Metro authorities stated the shutdown would last at least six months, or until "the necessary studies, corrections, and maintenance are carried out to ensure user safety". The line had been inaugurated just a few months earlier, on 30 October 2012, by Ebrard.[57] Twelve curves suffered significant damage in their tracks, and there was wear on the rails due to incompatibility with the FE-10 model trains. ICA, Grupo Carso and Alstom, the consortium that built the line, denied any wrongdoing. Bernardo Quintana, president of ICA, described the closure as "arbitrary" and stated that proper maintenance and measures to address the incompatibilities were necessary for the line to function correctly.[58] In addition, the Superior Auditor of the Federation detected a diversion of 7.5 billion pesos from the Secretariat of Communications and Transportation during the construction of the line.[59] Thirty-three officials and former officials, including Enrique Horcasitas, the director of the Line 12 project, were sanctioned with disqualifications from public service, fines, or both, due to project failures and cost overruns. The relationship between Mancera and Ebrard became strained amid efforts to investigate Ebrard for possible corruption, which he described as a smear campaign.[60][61]

The administration introduced a basic driving test for all new driver's license applicants. Previously, individuals only needed to present identification, proof of residence, and pay a fee, without having to demonstrate any driving knowledge or skill.[62] The environmental program Hoy No Circula, which restricts certain vehicles from circulating in the city one day a week based on their license plate number,[62] was expanded to two days per week over the course of the year.[63]

Third year

Mexico City's taxis had their traditional green color replaced with a white-and-Mexican-pink color scheme.[64] In May 2015, Mancera signed a law granting universal access to individuals accompanied by assistance dogs.[65] In July, Mancera reshuffled his cabinet, reassigning several secretaries to different positions.[66][67]

In the same month, Mancera's administration announced a major urban development project: the Corredor Cultural Creativo Chapultepec-Zona Rosa (Creative Cultural Corridor, or CCC), aimed at revitalizing Chapultepec Avenue, a thoroughfare connecting Chapultepec Park to the Zona Rosa neighborhood.[68] Mexican architect Fernando Romero was appointed to lead the design team, alongside architects Juan Pablo Maza and Ruysdael Vivanco.[69][70] The plan included preserving the avenue's trees and the Chapultepec aqueduct, while prioritizing pedestrian and cyclist access.[71] The project later received the International Architecture Award in the Urban Planning category.[70]

On 19 September, Mancera commemorated the 30th anniversary of the 1985 earthquake with a tribute that included a concert by Plácido Domingo, who had lost four relatives in a building collapse in Tlatelolco.[72] On 29 November, the government reopened all the Line 12 stations that had been closed in 2014.[73] In December, following a public consultation with residents of Cuauhtémoc, the borough where Chapultepec is located, 63 percent voted against the CCC project, leading to its official cancellation.[74]

Fourth year

Mancera inaugurated Line 6 of the Mexico City Metrobús on 21 January 2016, serving northern Mexico City from El Rosario metro station to Villa de Aragón metro station.[75] That same month, on 29 January, following a political reform, Mexico City, then officially known as the Federal District, was renamed Ciudad de México (City of Mexico), and commonly abbreviated as CDMX.[76] According to a March poll by El Universal, Mancera's approval rating had dropped to 24 percent and 57 percent of disapproval. Survey respondents identified insecurity, corruption, unemployment, and poverty as the most pressing issues.[77]

Mancera announced that for the first time since 2004, a Major League Baseball game would be held in Mexico City, as the Houston Astros and San Diego Padres played two exhibition games at Alfredo Harp Helú Stadium on 26 and 27 March.[78] In April, construction began on the westbound expansion of Line 12. The project included plans to build two additional stations and to extend the line's terminal at Observatorio metro station.[79] In July, the city distributed plastic whistles as a means of defense against sexual harassment targeting women, a measure that was criticized as ineffective.[80] In August, the city's public markets were designated intangible cultural heritage as a way to ensure their preservation.[81]

Fifth year

The city's constitution was enacted on 5 February 2017, and was set to take effect on 17 September 2018.[82] Mancera served as president of the National Conference of Governors from 3 May to 13 December 2017.[83][84] On 19 September 2017, a 7.1 Mw earthquake hit Mexico City at 13:14 CDT (18:14 UTC). He led the annual national drill commemorating the 1985 earthquake, held two hours earlier.[85] In the city, over 220 people died, at least 44 buildings collapsed, and over 3,000 others were evicted. There were nearly 6,000 complaints regarding construction violations since 2012. In 2016, Mancera had halted the law that allowed city departments to penalize Directors Responsible for Construction, the officials in charge of overseeing earthquake resilience. Critics like Josefina MacGregor from the association Suma Urbana, saw it as a way to prioritize urban development over safety. Mancera stated that new regulations were not a factor in the collapse, as many buildings had been constructed before 1985 and were not required to meet the updated standards. However, pre-1985 buildings with newer additions were required to comply with these regulations.[86][87]

Sixth year

Line 7 of the Metrobús system opened on 5 March 2018, running along Paseo de la Reforma.[88] On 29 March of that year, Mancera left the post of city head after requesting leave to run as a proportional-representation Senate candidate for the PAN in the July elections. José Ramón Amieva succeeded him as interim head of government.[89] Mancera left office with the lowest approval rating in 20 years, facing criticism over rising insecurity and affected by internal conflicts within the PRD.[90]

Investigations of Miguel Ángel Mancera's administration

When Claudia Sheinbaum took office as Mancera's successor as head of government of Mexico City, the city's Attorney General's Office launched several investigations. These focused on prosecuting various crimes and administrative offenses allegedly committed during Mancera's administration, including actions involving some of his close collaborators.[91] In 2020, 1,680 public servants were sanctioned by Mexico City Comptroller Office.[92] On 5 October 2020, the Electoral Tribunal of the Federal Judiciary sanctioned Mancera with a one-year disqualification to any public role in Mexico City after determining that he promoted a presidential candidate, Ricardo Anaya, in 2018, while being head of government, and sanctioned by Mexican electoral laws.[93]

Senator of the Republic

Mancera was elected as a senator and led the PRD's legislative caucus, despite having been elected through the PAN party.[94] On 6 March 2024, he was elected president of the Tourism Commission of the Senate.[95]

Personal life

Mancera has been married twice. His first marriage was to a woman named Martha in the early 1990s, with whom he lived in civil union for one year.[5] They divorced two years later. Six years later, Mancera married Magnolia, with whom he had two children.[5][10] After about a decade, he divorced Magnolia.[5] Mancera also has a daughter out of wedlock, but he has said the child's mother does not want him to have contact with her.[5] From 2008 to 2009, Mancera dated Alejandra Barrales,[5][10] who was then president of the PRD party,[96] and who sought to become the PRD candidate for Mayor of Mexico City in 2012.[22] In September 2007, two assailants on a motorcycle intercepted and attempted to rob Mancera while he was driving his BMW on Periférico Sur. His bodyguard intervened and shot one of the robbers, killing him.[10]

In his spare time, he practices various sports, including Krav Maga, indoor cycling, strength training, hunting and aviation.[97] On 31 October 2014, he underwent cardiac surgery after a cardiac arrhythmia was detected three months earlier.[98] During the surgery, he experienced a cardiac perforation.[98][99] He recovered two weeks later.[100]

Awards

In 2008, Mancera received the Alfonso Caso Award from the UNAM Faculty of Law, recognizing him as the most distinguished graduate of the doctoral program.[101] In September 2011, he was awarded the Latin American Prize for Life and Security of Women and Girls in Latin America and the Caribbean.[102] In February 2012, UNAM's Faculty of Law awarded Mancera the Raúl Carrancá y Trujillo Medal for his "academic and professional trajectory".[103]

Bibliography

- La Tentativa en el Código Penal para el Distrito Federal, una Nueva Propuesta (2003)[104]

- La Comisión por Omisión en el Nuevo Código Penal para el Distrito Federal (2003)[105]

- López Obrador Caso el Encino. Implicaciones Constitucionales, Penales y de Procedimiento Penal (2005)[101]

- Caso el Encino ¿Delito? (2005)[101]

- Nuevo Código para el Distrito Federal Comentado, Tomo III (2006)[106]

- Estudios Jurídicos en Homenaje a Olga Islas de González Mariscal, Tomo II (2007)[107]

- Estudios Jurídicos en Homenaje al Dr. Ricardo Franco Guzmán (2008)[101]

- Derecho Penal, Especialidad y Orgullo Universitario Papel del Abogado (2011)[101]

- Derecho Penal del enemigo (2011)[101]

- El Tipo de la Tentativa: Teoría y Práctica (2012)[108]

See also

Notes

References

- ^ a b c "Ventaja histórica de Mancera en el DF" [Historic lead for Mancera in the Federal District]. Expansión (in Spanish). 2 July 2012. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 11 July 2012.

- ^ a b Stevenson, Mark (23 June 2012). "Fading political left still thrives in Mexico City". Associated Press. Archived from the original on 25 July 2013. Retrieved 10 July 2012.

- ^ a b c d e "Miguel Ángel Mancera". Expansión (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 14 August 2015. Retrieved 5 July 2012.

- ^ a b c "Candidatos al GDF: Miguel Ángel Mancera Espinosa" [Candidates for Head of Government of the Federal District: Miguel Ángel Mancera Espinosa]. Terra (in Spanish). 1 February 2012. Archived from the original on 7 March 2016. Retrieved 9 July 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Tavira Álvarez, Alberto (11 January 2012). "Mancera, el exprocurador a fondo" [Mancera, the Former Attorney General in Depth]. Animal Político (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 12 July 2012. Retrieved 9 July 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Salcedo, Bejamín. "Asuntos Internos: Miguel Ángel Mancera" [Internal Affairs: Miguel Ángel Mancera]. Rolling Stone (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 12 July 2012. Retrieved 9 July 2012.

- ^ a b González Avelar, Víctor (7 January 2012). "Mancera o Beatriz" [Mancera or Beatriz]. El Diario de Coahuila (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 7 March 2016. Retrieved 9 July 2012.

- ^ Camp, Roderic Ai (2011). Mexican Political Biographies, 1935 – 2009 (4th ed.). Austin, Texas: University of Texas Press. p. 584. ISBN 9780292729926. OCLC 753978359.

- ^ a b c d e "Profesores de Asignatura: Mancera Espinosa, Miguel Ángel" [Course Professors: Mancera Espinosa, Miguel Ángel] (in Spanish). Instituto Tecnológico Autónomo de México. Archived from the original on 21 February 2013. Retrieved 10 July 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f g Páramo, Arturo (9 June 2012). "Perfil: Miguel Ángel Mancera Espinosa" [Profile: Miguel Ángel Mancera Espinosa]. Excélsior (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 24 June 2015. Retrieved 9 July 2012.

- ^ a b "Mancera se registra como candidato del PT al GDF" [Mancera registers as PT candidate for the Government of the Federal District]. Red Política (in Spanish). 26 January 2012. Archived from the original on 23 June 2015. Retrieved 9 July 2012.

- ^ "Mancera, a la sombra incómoda de Regino" [Mancera, in the uncomfortable shadow of Regino]. El Universal (in Spanish). 16 July 2008. Archived from the original on 4 February 2016.

- ^ Martínez, Fernando; Cuenca, Alberto (8 July 2012). "Va Mancera de encargado de la PGJDF" [Mancera appointed Head of the Mexico City Attorney General's Office]. El Universal (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 12 October 2018. Retrieved 5 December 2012.

- ^ "El procurador del DF deja el cargo para contender por el gobierno local" [The Attorney General of Mexico City leaves the position to run for local government]. Expansión (in Spanish). 6 January 2012. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 11 July 2012.

- ^ "5 episodios relevantes de Ebrard en la capital" [5 key episodes of Ebrard in the capital]. Expansión (in Spanish). 22 September 2011. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 11 July 2012.

- ^ a b "Destacan en EU elección de Mancera sin impugnaciones" [The United States noted that Mancera's election proceeded without any legal challenges or disputes]. MVS Noticias (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 2 October 2014. Retrieved 20 December 2017.

- ^ Yañez, Israel (10 January 2012). "Desarticulan 179 bandas delicitivas durante el 2011" [179 criminal gangs dismantled during 2011]. La Crónica de Hoy (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 20 July 2013.

- ^ Martínez, Paris (23 January 2012). "Los delitos durante la gestión de Mancera" [Crime rates during Mancera's administration]. Animal Político (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 6 June 2016. Retrieved 20 December 2017.

- ^ Bolaños, Claudia (7 January 2012). "Sucesor de Mancera dará continuidad a programas" [Mancera's successor to continue existing programs]. El Universal (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 16 October 2015. Retrieved 3 July 2012.

- ^ Robles, Johana (8 January 2012). "Mancera Espinosa registra en el PRD precandidatura" [Mancera Espinosa registers as a PRD pre-candidate]. El Universal (in Spanish). Retrieved 3 July 2012.

- ^ Robles, Johana (19 January 2012). "Izquierdas arropan a Mancera para el GDF" [Left-wing parties rally behind Mancera for the Head of Government of the Federal District]. El Universal (in Spanish). Retrieved 3 July 2012.

- ^ a b Robles, Johana; Villanueva, Jonatha (19 January 2012). "Mancera, virtual candidato al GDF por la izquierda" [Mancera, assumed left-wing candidate for Head of Government of the Federal District]. El Universal (in Spanish). Retrieved 3 July 2012.

- ^ "Tras un mes de campaña, aspirantes al GDF se enfrentan a la realidad de la ciudad" [After a month of campaigning, candidates for Head of Government of Mexico City face the realities of the city]. La Jornada (in Spanish). 27 May 2012. Archived from the original on 16 April 2021. Retrieved 30 July 2025.

- ^ "Mancera supera en 23 puntos porcentuales a Paredes: Mitofsky" [Mitofsky: Mancera leads Paredes by 23 percentage points]. ADNPolítico (in Spanish). 2 February 2012. Archived from the original on 10 March 2012. Retrieved 12 July 2012.

- ^ "Encuesta de El Universal reporta que Mancera pierde 9 puntos" [El Universal poll reports Mancera drops 9 points]. ADNPolítico (in Spanish). 20 March 2012. Archived from the original on 24 April 2012. Retrieved 12 July 2012.

- ^ Robles, Johana (24 April 2012). "Mancera encabeza preferencias; aumenta 5 por ciento" [Mancera leads in the polls; support increases by 5 percent]. El Universal (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 12 July 2012.

- ^ Robles, Johana (21 May 2012). "Crece ventaja de Mancera en el DF" [Mancera's lead grows in the Federal District]. El Universal (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 12 July 2012.

- ^ "Pasan 'Charola' a empresarios, piden 6mdd para AMLO" [Business leaders asked to 'pass the hat around' seeking $6 million for AMLO]. La Prensa (in Spanish). 31 May 2012. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 7 October 2015.

- ^ "Mancera presenta denuncia por 'charolazo'" [Mancera files complaint over fundraising scandal]. La Razón (in Spanish). 31 May 2012. Archived from the original on 27 May 2024. Retrieved 7 October 2015.

- ^ "Miguel Ángel Mancera ofrece continuar las políticas de Marcelo Ebrard" [Miguel Ángel Mancera offers to continue Marcelo Ebrard's policies]. Expansión (in Spanish). 12 January 2012. Archived from the original on 21 December 2016. Retrieved 12 July 2012.

- ^ "Las noticias de hoy. Resumen Eduardo Ruiz Healy" [Today's News. Summary by Eduardo Ruiz Healy]. Radio Fórmula (in Spanish). 1 May 2012. Archived from the original on 20 December 2016. Retrieved 12 July 2012.

- ^ "Propone Mancera a citadinos disminuir trayectos a 30 minutos, de casa a trabajo" [Mancera proposes reducing commutes to 30 minutes, from home to work, for city residents]. Excélsior (in Spanish). 27 May 2012. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 12 July 2012 – via Archived by Instituto Nacional del Fromación Política PRD.

- ^ "Aventaja Miguel Ángel Mancera elección por GDF" [Miguel Ángel Mancera leads the race for Head of Government of Mexico City]. W Radio (in Spanish). 1 July 2012. Archived from the original on 6 March 2016. Retrieved 12 July 2012.

- ^ "Recibe Miguel Ángel Mancera la constancia de mayoría" [Miguel Ángel Mancera receives the certificate of majority]. La Crónica de Hoy (in Spanish). 8 July 2012. Archived from the original on 8 July 2012. Retrieved 9 July 2012.

- ^ Osorio, Ernesto (7 July 2012). "Ya es Mancera Jefe de Gobierno electo" [Mancera officially named Head of Government-elect]. Reforma (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 13 January 2017. Retrieved 10 July 2012 – via Terra.

- ^ a b "Recibe Mancera constancia como jefe de Gobierno electo" [Mancera receives certificate as Head of Government-elect]. ADN Político (in Spanish). 8 October 2010. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 7 October 2015.

- ^ "Miguel Ángel Mancera recibe constancia como jefe de gobierno electo del DF" [Miguel Ángel Mancera receives certificate as Head of Government-elect of the Federal District]. Aristegui Noticias (in Spanish). 8 December 2012. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 7 October 2015.

- ^ Macías, Verónica; Hernández, Dedenhi (5 December 2012). "Mancera ya es Jefe de Gobierno, promete obedecer" [Mancera is now Head of Government, promises to comply]. El Economista (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 21 December 2017. Retrieved 7 October 2015.

- ^ Sánchez, Enrique; Castillejos, Jessica; Ramírez, Kenya; Pazos, Francisco (6 December 2012). "GDF y Los Pinos abren nueva etapa; Mancera rinde protesta" [Federal District Government and Los Pinos open a new chapter; Mancera takes oath of office]. Excélsior (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 8 August 2025. Retrieved 30 July 2025.

- ^ "Mancera invita a unirse a programa de desarme" [Mancera invites the public to join the disarmament program]. El Universal (in Spanish). 22 December 2012. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 9 January 2013.

- ^ "Desarme en Iztapalapa acumula 866 armas en 10 días" [Disarmament in Iztapalapa collects 866 weapons in 10 days]. Excélsior (in Spanish). 2 January 2013. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 9 January 2013.

- ^ "Desarme voluntario se extiende en el DF" [Voluntary disarmament extended throughout the Federal District]. Zócalo Saltillo (in Spanish). 21 January 2013. Archived from the original on 10 June 2013. Retrieved 7 October 2015.

- ^ Valdéz, Ilich (8 December 2014). "Rebasa meta de desarme voluntario en el DF en 2014" [Voluntary disarmament in the Federal District surpasses its 2014 goal]. Milenio. Archived from the original on 21 June 2015. Retrieved 7 October 2015.

- ^ Galván, Eduardo (22 June 2015). "Arranca en GAM programa de desarme voluntario" [Voluntary disarmament program begins in Gustavo A. Madero]. Milenio. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 7 October 2015.

- ^ "Miguel Ángel Mancera es el 'alcalde del mes', según City Mayors" [Miguel Ángel Mancera named 'Mayor of the Month', according to City Mayors]. Expansión. 3 June 2025. Archived from the original on 31 March 2021. Retrieved 31 July 2025.

- ^ "Mancera inaugura Línea 5 del Metrobús". El Economista (in Spanish). 5 November 2013. Retrieved 5 August 2025.

- ^ "Proponen subir a 5 pesos precio del metro" [Proposal made to raise Metro fare to 5 pesos]. El Economista (in Spanish). Notimex. 14 November 2013. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 8 December 2013.

- ^ Rodríguez, Darinka (6 December 2013). "¿Cuál es el impacto al bolsillo del aumento a la tarifa del metro?" [What is the financial impact of the Metro fare increase?]. El Financiero (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 7 October 2015.

- ^ "¿Cuánto cuesta el Metro y salario en otros países?" [How much do the Metro fare and wages cost in other countries?]. El Universal (in Spanish). 7 December 2013. Archived from the original on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 28 November 2013.

- ^ "Inicia encuesta sobre incremento a tarifa del Metro" [Survey begins on Metro fare increase]. Milenio (in Spanish). Mexico City. Notimex. 29 November 2013. Archived from the original on 8 August 2025. Retrieved 31 July 2025.

- ^ Hernández, Enrique (30 November 2013). "Consideran una burla que 7,200 decidan por más de 5.5 millones" [Considered an insult that 7,200 people should decide for more than 5.5 million]. La Prensa (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 8 December 2013.

- ^ "El viaje en el Metro del DF costará 5 pesos a partir del 13 de diciembre" [The Mexico City Metro fare will cost 5 pesos starting 13 December]. Expansión (in Spanish). 6 December 2013. Archived from the original on 12 May 2017. Retrieved 8 December 2013.

- ^ Adrián, Jazmín (7 December 2013). "Civil disobedience over Metro price hike in Mexico City". Demotix. Archived from the original on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 8 December 2013.

- ^ Wilkinson, Tracy; Sanchez, Cecilia (28 December 2013). "Mexico City subway rate increase enrages commuters". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 31 October 2015. Retrieved 7 October 2015.

- ^ "El GDF va contra la campaña para pasar al Metro sin pagar" [The Federal District government takes action against the campaign encouraging fare evasion on the Metro]. ADNPolítico (in Spanish). 8 December 2013. Archived from the original on 11 December 2013. Retrieved 8 December 2013.

- ^ "Va GDF contra quien brinque torniquetes" [The Federal District government is cracking down on those who jump the turnstiles]. Milenio (in Spanish). 8 December 2013. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 8 December 2013.

- ^ Ramos, Dulce (11 March 2014). "Línea 12 del metro cierra 12 estaciones por seis meses" [Line 12 of the Metro closes 12 stations for six months]. Animal Político (in Spanish). Notimex. Archived from the original on 22 June 2025. Retrieved 1 August 2025.

- ^ Navarro, Ulises (20 March 2014). "ICA acusa a GDF por cierre arbitrario de la Línea 12" [ICA blames Mexico City government for the "arbitrary" closure of Line 12]. Alto Nivel (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 8 August 2025. Retrieved 1 August 2025.

- ^ Romero, Gabriela; Gómez, Laura; Cruz, Alejandro (14 March 2014). "Detecta la ASF desvíos en Línea Dorada por casi $7 mil millones" [The Superior Auditor of the Federation detects nearly 7 billion pesos in diverted funds for the Golden Line]. La Jornada (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 7 February 2021. Retrieved 1 August 2025.

- ^ "L12 confronta a Mancera y a Ebrard" [Line 12 confronts Mancera and Ebrard]. máspormás (in Spanish). 11 September 2014. Archived from the original on 19 June 2021. Retrieved 2 August 2025.

- ^ Romero Puga, Juan Carlos (5 May 2021). "Fantasmas de la línea 12" [Ghosts of Line 12]. Letras Libres (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 9 November 2024. Retrieved 2 August 2025.

- ^ a b Grant, Will (21 September 2014). "How I got my driving licence without a test". BBC News. Mexico City. Archived from the original on 30 September 2023. Retrieved 2 August 2025.

- ^ Martínez, Marco Antonio (15 September 2014). "Dialogar mayor acierto de Mancera; error, doble Hoy no circula: PAN DF" [Mancera's greatest success was dialogue; his mistake was doubling Hoy No Circula: PAN CDMX]. Quadatrín (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 8 August 2025. Retrieved 4 August 2025.

- ^ Wilkinson, Tracy (5 January 2015). "Mexico City wants cabbies to color their taxis pink". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 6 March 2025. Retrieved 5 August 2025.

- ^ "Mexico City mayor signs ordinance giving service dogs access to public spaces". The San Diego Union-Tribune. Mexico City. EFE. 26 May 2015. Retrieved 5 August 2025.

- ^ "Mancera realiza cambios en su gabinete" [Mancera performs changes to his cabinet]. Forbes (in Spanish). 16 July 2015. Archived from the original on 10 May 2016. Retrieved 5 August 2025.

- ^ "Así es el nuevo gabinete de Miguel Ángel Mancera" [This is the new cabinet of Miguel Ángel Mancera]. El Economista (in Spanish). 17 July 2015. Archived from the original on 8 August 2025. Retrieved 5 August 2025.

- ^ Páramo, Arturo (29 July 2015). "Doble piso peatonal en Corredor Cultural Chapultepec-Zona Rosa" [Double-level pedestrian walkway on the Chapultepec–Zona Rosa Cultural Corridor]. Excélsior (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 30 September 2015. Retrieved 7 October 2015.

- ^ "Fernando Romero Reveals Plans for a New Linear Park in Mexico City". Designboom. 18 August 2015. Archived from the original on 21 October 2015. Retrieved 7 October 2015.

- ^ a b Cruz Pérez, Héctor (28 July 2015). "Conoce el Proyecto del Parque Elevado en Avenida Chapultepec" [Explore the elevated park project on Avenida Chapultepec]. Chilango (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 21 October 2015.

- ^ Quesada, Juan Diego (27 August 2015). "Romero: 'El Corredor de Chapultepec es una oportunidad única'" [Romero: 'The Chapultepec Corridor is a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity']. El País (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 9 January 2018. Retrieved 7 October 2015.

- ^ Altamirano, Claudia (19 September 2015). "'Todo está tan vivo': Plácido Domingo vuelve a Tlatelolco" ['Everything is so alive': Plácido Domingo returns to Tlatelolco]. Nexos (in Spanish). Retrieved 5 August 2025.

- ^ Martínez Brooks, Darío (29 November 2015). "Línea 12 del Metro reabre todas sus estaciones tras 20 meses" [Line 12 reopens all its stations after 20 months]. Expansión (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 29 April 2016. Retrieved 5 August 2025.

- ^ Cruz, Daniela (10 December 2015). "Cancelan oficialmente proyecto propuesto para el Corredor Cultural Chapultepec en México" [Proposed project Chapultepec Cultural Corridor in Mexico officially canceled]. ArchDaily (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 29 October 2021. Retrieved 5 August 2025.

- ^ Rodea, Felipe (21 January 2025). "Mancera inaugura Línea 6 del Metrobús" [Mancera inaugurates Mexico City Metrobús Line 6]. El Financiero. Archived from the original on 25 January 2025. Retrieved 5 August 2025.

- ^ "¡Adiós DF, bienvenida CdMx!: Mancera" [Mancera: Farewell Federal District, welcome Mexico City!]. Milenio (in Spanish). 29 January 2016. Archived from the original on 18 November 2024. Retrieved 5 August 2025.

- ^ "Baja popularidad de Miguel Ángel Mancera" [Public support for Mancera falls]. López-Dóriga Digital (in Spanish). 14 March 2016. Archived from the original on 17 March 2016. Retrieved 5 August 2025.

- ^ "Major League Baseball to return to Mexico City in March". Fox News. 14 January 2016. Archived from the original on 1 August 2021. Retrieved 5 August 2025.

- ^ Sarabia, Dalila (7 July 2021). "'Dañaron casas y familias': Desde hace 5 años, ampliación de Línea 12 trastorna Álvaro Obregón" ['Homes and families are affected': For 5 years, Line 12 expansion has disrupted Álvaro Obregón]. Animal Político (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 7 July 2021. Retrieved 5 August 2025.

- ^ Estrella, Alferdo (8 July 2016). "Mexico City's weapon against sexual assault: whistles". The Peninsula. Agence France-Presse. Archived from the original on 8 August 2025. Retrieved 5 August 2025.

- ^ "Los Mercados son declarados Patrimonio Cultural Intangible" [Markets are designated Intangible Cultural Heritage]. El Universal (in Spanish). Notimex. 16 August 2016. Archived from the original on 17 August 2016. Retrieved 5 August 2025.

- ^ "¿Conoces la nueva Carta Magna de la CDMX?" [Do you know about Mexico City's new Constitution?]. Fundación UNAM (in Spanish). 17 August 2017. Archived from the original on 25 March 2018. Retrieved 6 August 2025.

- ^ Hernández, Sandra (3 May 2017). "Mancera asume presidencia de la Conago" [Mancera assumes presidency of the National Conference of Governors (Conago)]. El Universal (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 12 November 2020. Retrieved 7 August 2025.

- ^ Ramírez, Juan (13 December 2017). "Mancera deja presidencia de Conago en reunión ordinaria" [Mancera leaves presidency of Conago at ordinary meeting]. La Silla Rota (in Spanish). Retrieved 7 August 2025.

- ^ "El simulacro que casi se realiza durante un terremoto de verdad" [The drill that was almost held during a real earthquake]. CNN en Español (in Spanish). 19 September 2017. Archived from the original on 24 June 2025. Retrieved 7 August 2025.

- ^ Pskowski, Martha; Adler, David (12 October 2017). "6,000 complaints ... then the quake: the scandal behind Mexico City's 225 dead". The Guardian. Mexico City, London. Archived from the original on 14 March 2025. Retrieved 7 August 2025.

- ^ Linthicum, Kate (12 September 2018). "Corruption caused the collapse of buildings in 2017 Mexico City earthquake, a new report finds". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 1 December 2024. Retrieved 7 August 2025.

- ^ "La accidentada primera semana de la L7 del Metrobús" [A bumpy start for Metrobús Line 7]. Milenio (in Spanish). Mexico City. 13 March 2018. Archived from the original on 27 January 2019. Retrieved 7 August 2025.

- ^ Álvarez Acevedo, Carlos (29 March 2018). "Miguel Ángel Mancera pide licencia como jefe de Gobierno de la Ciudad de México; será candidato a senador" [Miguel Ángel Mancera requests leave as head of government of Mexico City; will run for senate]. Zeta (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 1 July 2018. Retrieved 7 August 2025.

- ^ "Los claroscuros de Miguel Ángel Mancera en la CDMX" [The highs and lows of Miguel Ángel Mancera in Mexico City]. Expansión (in Spanish). 8 April 2018. Archived from the original on 21 May 2022. Retrieved 7 August 2025.

- ^ Pantoja, Sara. "Sheinbaum pide dar seguimiento a investigación por corrupción en gobierno de Mancera" [Sheinbaum asks to follow up on corruption investigation in Mancera government]. Proceso (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 26 October 2020. Retrieved 22 October 2020.

- ^ Cruz Flores, Alejandro (12 August 2020). "Sancionó Contraloría local a mil 680 servidores de esta gestión y anterior" [The local Comptroller sanctioned 1,680 public servants from this and the previous administration]. La Jornada (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 8 March 2025. Retrieved 22 October 2020.

- ^ Robles, Johana (22 October 2020). "Inhabilitan a Mancera por un año en la CDMX" [Mancera is disqualified for a year in Mexico City]. El Universal (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 23 October 2020. Retrieved 22 October 2020.

- ^ Teposteco, Miguel (15 August 2018). "Ya es oficial: 'el independiente' Mancera lidera PRD en Senado" [It's official: 'the independent' Mancera leads the PRD in the Senate]. La Hoguera (in Spanish). Retrieved 7 August 2025.

- ^ "Asume el senador Miguel Ángel Mancera, presidencia de la Comisión de Turismo" [Senator Miguel Ángel Mancera assumes presidency of the Tourism Commission] (in Spanish). LXIV Legislature of the Mexican Congress. 6 March 2024. Retrieved 7 August 2025.

- ^ "Confirman que Alejandra Barrales dejará la dirigencia del PRD en el DF" [Confirmed that Alejandra Barrales to step down as head of the PRD in Mexico City]. esmas.com (in Spanish). 29 January 2012. Archived from the original on 3 August 2019. Retrieved 27 November 2012.

- ^ "10 facetas desconocidas de Miguel Ángel Mancera" [10 lesser-known facets of Miguel Ángel Mancera]. ADNPolítico (in Spanish). 20 January 2012. Archived from the original on 17 November 2015. Retrieved 11 July 2012.

- ^ a b Navarro, Israel; Domínguez, Pedro (1 November 2015). "Perforación cardiaca ocasionó cirugía de Mancera" [Cardiac perforation led to Mancera’s surgery]. Excélsior (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 7 October 2015.

- ^ Ramírez, Kenya; Pazos, Francisco (1 November 2015). "Se complica operación de Mancera" [Mancera's surgery complicates]. Milenio (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 7 October 2015.

- ^ Montes, Rafael (18 November 2014). "Mancera reaparece en evento público tras operación de corazón" [Mancera reappears at public event after heart surgery]. El Financiero (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 2 December 2024. Retrieved 7 October 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f "Miguel Ángel Mancera Espinosa". Red Politica (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 27 August 2015. Retrieved 13 July 2012.

- ^ "Por la vida y la seguridad de las mujeres y las niñas en AL" [For the life and safety of women and girls in Latin America] (in Spanish). Mexico: Comunicación e Información de la Mujer AC. 24 September 2010. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 7 October 2015.

- ^ Cruz Monroy, Filiberto (9 February 2012). "Condecoran a Miguel Ángel Mancera en la UNAM" [Miguel Ángel Mancera honored at UNAM]. Excélsior (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 7 October 2015.

- ^ García Ramírez, Sergio; Vargas Casillas, Leticia A.; et al. (2003). Proyectos legislativos y otros temas penales: Segundas Jornadas sobre Justicia Penal. Doctrína jurídica (in Spanish). Vol. VIII (I ed.). Mexico: National Autonomous University of Mexico. pp. 115–124. ISBN 970-32-0313-2. OCLC 52004788. No. 129.

- ^ García Ramírez, Sergio; Islas de González Mariscal, Olga; et al. (2003). Análisis del Nuevo Código Penal Para el Distrito Federal: Terceras Jornadas sobre Justicia Penal "Fernando Castellanos Tena". Doctrína jurídica (in Spanish) (I ed.). Mexico: National Autonomous University of Mexico. ISBN 970-32-0568-2. OCLC 53836151. No. 144. Archived from the original on 8 January 2018. Retrieved 8 January 2018.

- ^ García Ramírez, Sergio; Islas de González Mariscal, Olga; et al. (2006). Nuevo Código para el Distrito Federal Comentado. Libro Segundo (Artículos 250 al 365 y Transitorios) Tomo III. Doctrína jurídica (in Spanish). Vol. XIX (I ed.). Mexico City: National Autonomous University of Mexico. Editorial Porrúa. ISBN 9700766799. OCLC 254345014. No. 348.

- ^ García Ramírez, Sergio; et al. (2007). Estudios Jurídicos en Homenaje a Olga Islas de González Mariscal, Tomo II. Doctrína jurídica (in Spanish) (I ed.). Mexico: National Autonomous University of Mexico. ISBN 978-970-32-439-14. OCLC 166310075. No. 129. Archived from the original on 8 January 2018. Retrieved 8 January 2018.

- ^ "Presentan libro de Mancera" [Mancera's book unveiled]. La Razón (in Spanish). 4 April 2012. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 14 July 2012.