Melbourne Central Shopping Centre

| |

| |

| Location | Melbourne, Victoria, Australia |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 37°48′37.42″S 144°57′47.32″E / 37.8103944°S 144.9631444°E |

| Opening date | September 1991[1] |

| Developer | Kumagai Gumi |

| Management | GPT Group |

| Owner | GPT Group[2] |

| Architect | Hassel with Kisho Kurokawa (1991), Ashton Raggatt McDougall (2002-2005 & 2010-2011) |

| No. of stores and services | 276[3] |

| No. of anchor tenants | 2[3] |

| Total retail floor area | 55,700 square metres (600,000 sq ft)[3] |

| No. of floors | 6[4] |

| Parking | 876[3] |

| Public transit access | Melbourne Central railway station, trams, buses |

| Website | melbournecentral |

Melbourne Central is a large shopping centre, office, and public transport hub in the central business district of Melbourne, Victoria, Australia. The main tower is 211-metre (692 ft) high, making it one of the tallest buildings in Melbourne at the time it was built in 1991. Other parts of the complex include the Melbourne Central Shopping Centre, the underground Melbourne Central railway station and the heritage-listed Coop's Shot Tower.

The site of the present-day complex was earmarked for development in the early 1970s by the Melbourne City Council.[5] At the time, the State Government of Victoria had started constructing the City Loop underground railway with a station located on the site called Museum Station.[6] The main tower and complex was completed in 1991, designed by Japanese architect Kisho Kurokawa and the Kumagai Gumi at a cost of $1.2 billion.[5][7] It has since been significantly renovated three times in 2001, 2005 and 2010.

Today the centre features a gross leasable area of 55,100 square metres (593,000 sq ft) spread over six floors.[2] The 20 storey glass conical structure over the Coop's Shot Tower is the largest of its kind in the world[5] and over 8.6 million passengers pass through the Melbourne Central station every year.[8]

History

20th Century

Background

Originally termed the 'Victoria Project',[9] large scale redevelopment of the city block bounded by Lonsdale, Swanston, La Trobe and Elizabeth Streets was studied in some detail during the 1960s and 1970s, being closely linked with work on the City Loop Early work on the site commenced in 1971 when land on the south side of La Trobe Street was acquired, to enable the cut and cover construction of Museum Station (now known as Melbourne Central). With planning for the site being carried out by the Melbourne Underground Rail Loop Authority from 1980, the railway station opened in 1981, but protracted negotiations failed to find an anchor tenant for the development, resulting in the State Government of Victoria deciding in 1983 that a private developer should be sought.[6]

Design

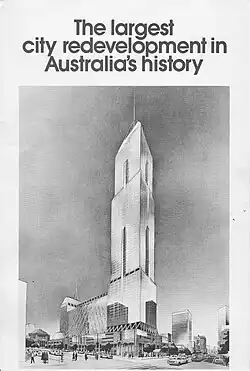

By the time registrations closed in March 1984 a total of 28 submissions had been received from developers, with eight selected organisations invited to respond.[6] A government panel sat in April 1985 to evaluate the responses, and one month later announced their preferred scheme: designed by Hassell Architects for EKG Developments, a joint venture between Australian property developer Essington Limited and Japanese construction firm Kumagai Gumi.[6] The project compromised an 85 floor office tower, with a hotel at the Swanston Street end, joined by a huge sloping walled atrium 20 floors high, over a shopping atrium opening down to the station platforms, designed by Hassell.[10]

The $1.2 billion contract was signed soon after but without Essington Limited, who were removed by the State Government after a number of directors were linked to the Nugan Hand Bank.[11] It was also at this time that Kisho Kurokawa was brought on board as architect, with Hassell and Bates, Smart & McCutcheon compensated by becoming the joint documenters of the scheme. It was also scaled back, with the hotel removed, and the office tower reduced to 72 storeys and then 55, and the atrium reduce to a tall cone, and a circular opening through the shopping levels. An arm of shops connecting to Lonsdale Street was also added, replacing 19th century warehouses,[12] and via footbridges connected through to the Myer store. An anchor tenant was also found, with Japanese department store Daimaru signed on over six floors of the shopping centre due to the involvement of the Japanese Sumitomo Bank on the project.[6][7] Connell Wagner were the civil and structural engineers for the project. Mechanical, electrical and hydraulic services were provided by Norman Disney & Young. Rankin & Hill did the fire services.[13]

1990s: Opening

Melbourne Central opened on 11 September 1991 with 160 specialty stores, 30 cafes and food outlets and a six level Japanese department store Daimaru which was the first store to open in Australia. Around 3,000 people attended the opening of Melbourne Central, and it came with a motto as “the life of the city".[14]

The Daimaru department store was an attempt to compete with nearby Australian established department stores such as Myer, Georges and David Jones.[15][11]

Melbourne Central is built on top of the existing Museum Station (now known as Melbourne Central Station) with direct access to the shopping centre and station concourse via escalators. The Melbourne Central Office Tower is a 210 metres (690 ft) high with 57 storeys with 46 of used for office. The shopping centre contains six levels of retail built around the existing the 50-metre (160 ft) high heritage listed Coops Shot Tower which was built in 1888. The tower became a focal point and symbol of Melbourne Central. It is enclosed by an 80-metre (260 ft) high glass cone known as the "Magic Cone". It weighs 490 tonnes and has 924 glass panes. The cone is the largest of its kind in the world and was built in reference to the large dome of the adjacent State Library of Victoria. A hot-air balloon and a biplane dangled in mid-air underneath the cone.[16]

The original six levels of retail were organised into five different areas known as 'shopping worlds' - Historic World, Crystal World, Action World, Urban World and International World.[17]

Melbourne Central also featured a giant video screen, murals depicting trades throughout the ages, a rooftop amusement park, a three-storey glass butterfly enclosure, waterfall water feature and the famous Marionette Watch. The Marionette Watch was designed by Seiko and is located opposite the Shot Tower and hangs off level two and was connected to a twelve and a half metre, two tonne chain. Every hour, on the hour, a marionette display drops down from the bottom of the watch with an Australian galahs, cockatoos and two minstrels performing Waltzing Matilda, under the watchful gaze of some koalas.[14]

The centre has a large multi-level underground carpark with over 1,600 spaces and also has an undercover footbridge across Lonsdale and Little Lonsdale streets which links through to Myer and the CBD retail heart on Bourke Street.[14]

On 11 September 1993 a 2,300m² Toys "R" Us store opened on the ground level of Melbourne Central.[18] The opening of the store attracted a record of 250,000 people at the time.[19]

Melbourne Central was the film location of Mr. Nice Guy which was released in 1997 and stared Jackie Chan.[20][21]

In May 1999, GPT Group purchased 97.1% stake of Melbourne Central from Kumagai Gumi for $408 million after a five-year sale.[22][23] Kumagai Gumi never made a profit on Melbourne Central and was forced to sell the ownership of the centre whilst retaining the 2.9% stake to write the asset off over 20 years. In 2001 Kumagai Gumi sold their remaining share to GPT for $17 million.[24]

21st Century

2000s

On 25 September 2001, Daimaru Inc announced that it would close and liquidate its two stores in Australia. The store in Pacific Fair on the Gold Coast closed on 31 January 2002 and in Melbourne Central Daimaru closed on 31 July 2002.[25][26] Daimaru paid $30 million for their five years of remaining rent in return for abandoning their lease agreement which was to expire in 2016.[24][27] Daimaru never turned a profit on the store, costing its shareholders approximately $200 million. With half the total retail space empty due to the loss of Daimaru, GPT announced a $195 million plan to renovate the centre in April 2002 by refitting the old Daimaru space into mini majors, specialty stores, entertainment and leisure on the upper levels and a new lower ground level on the existing station concourse.[24][28][29][30]

Work began on the $200 million redevelopment in September 2002 and it was designed by architects Ashton Raggatt McDougall and ARM Architecture who described it as a "tired, old building", inappropriate for Melbourne.[31] It aimed to open the complex to more natural light, new street-front shopping strips, and bubble-like additions to the footbridge across Little Lonsdale Street but largely compromised the design of Kurokawa.[6][32]

Work began on the access to the adjacent Melbourne Central railway station in December 2002 with the temporary closure of the La Trobe Street entrance and redirected commuters to the Elizabeth and Swanston Street entrances. This stage of construction involves linking the station concourse with the Lonsdale Street building occupied by Toys "R" Us. Toys "R" Us vacated its spot in January 2003 following lease termination agreement. This development created a new lower ground level which spans from Lonsdale Street to La Trobe Street. This level incorporates a new Coles Express supermarket (now Coles Central), a fresh food and essential service precinct, a food court with McDonald's, KFC and six food outlets and a new ticket booth outlet for the station.[27]

This development removed direct access to the station concourse from Swanston Street with the escalators closed in November 2003 and were replaced by escalators that direct commuters into the atrium under the cone in the centre of the shopping centre, making the path for rail passengers more convoluted. The concourse under La Trobe Street was integrated into the shopping centre with the installation of numerous shops. This development faced a lot of criticism due to the original complex which had a direct entrance to the underground concourse from the tram stop on Swanston Street removed in favour of a much longer route through the shopping centre.[33][34] The company operating Melbourne's suburban railways at the time, M>Train, together with the owners of Melbourne Central, closed this direct entrance which caused overcrowding and delays to passengers attempting to access the station platforms.[35][36][37][38]

Other parts of Melbourne Central were renovated during this $200 million development. The ground level was replaced by specialty stores which specialized in "street urban fashion stores". A lane way was carved through the centre from La Trobe Street to Little Londale Street to reflect Melbourne's laneway culture.[27]

Level one and two specialized in cosmetics, homewares, books and music. A Borders bookstore opened on level one and Freedom Furniture opened on level two.[27]

Parts of the centre have opened progressively in the months of 2004 with the entire redevelopment excluding levels 3 - 5 completed in December 2004.[39][40]

On 20 September 2005 a 12 screen Hoyts Cinema opened on levels 3 and 4.[41] The opening of the cinema resulted in the closure of the Hoyts Cinema complex on Bourke Street.[42][43] The rest of Level 3 including the Melbourne Central Lion Hotel, entertainment venues and various restaurants and bars had opened up by the end of 2005. The Kingpin Bowling Alley (which operated until 2009) opened in 2006.[39]

The renovation took the book value of the complex to $1033 million in 2010,[7] up from $229.8 million as of at 31 December 2001.[24]

2010s

On 23 June 2010 plans for a $75 million redevelopment were unveiled by GPT. It was done in two stages and designed by the same Ashton Raggatt McDougall Architects from its 2002 - 2005 redevelopment.[7][44]

The first stage of the $75 million redevelopment started in September 2010 at a cost of $30 million. This development involved the closure and relocation of the Level 2 'Food on Two' food court.[45]

In late March 2011, a large food court known as the 'Dining Hall' opened on the former space of Freedom Furniture on level two.[46] The new food court contains 16 diverse range of food outlets including fast food options such as McDonald's to local individual outlets.[47] A new entrance at Elizabeth Street provided access to the food court from the street and created another cross-block connection through the centre.[48][45]

In August 2011, a new fashion precinct on the north-eastern side of the centre known as 'The Corner' opened. The Corner contains a mix of international and local urban fashion and lifestyle brands including Nike, Glue, Hype DC, Jeanswest and a Converse flagship store.[49] The Glue store opened on 13 December 2011 on the space of the former 'Food on Two' food court. A new side entrance from the corner of Swanston and La Trobe Street provided access to The Corner from the street. The entrance to The Corner is marked by a unique new architectural feature feature known as 'The Tree' was added and is designated as an iconic Melbourne meeting point.[50]

On 26 April 2012 Strike Bowling opened its venue on level three on the former Kingpin Bowling space. The opening was promoted with a VIP launch party and a social media-driven stunt where the Strike Bowling social media manager was lifted by helium balloons in the shopping centre with more helium added for each engagement on social platforms.[51]

In late 2017, JB Hi-Fi opened its store on level one.[52]

Criticism

During the early stages of planning in the late 1960s and early 1970s, the lack of certainty on the site's future was criticised by some existing property owners, residents and business operators due to the perceived negative impact on land values.[6] Confirmed design intentions were not publicly revealed until 1985 following a lengthy tender evaluation and committee process.[6] There was criticism throughout the design and construction phases of the complex's impacts on heritage and neighbourhood character. At the time of its early planning the prevailing attitude from government planners was that the traditional layout of the central city with small laneways and buildings was old-fashioned and not suited to a modern metropolis. This was reflected in the final design of the complex as a single building using almost an entire city block.[6] As a result, four laneways and many other buildings were demolished to make way for the new structures.[53]

Although generally acknowledged as a successful design and development,[6] several groups and individuals criticised certain aspects of the building. For example, the Victorian Chamber of Commerce, National Trust of Australia and heritage preservation groups opposed the link bridges between Melbourne Central and the Myer department store on the grounds that it would discourage people from walking at street level and reduce patronage to smaller businesses.[54]

Complex

Office tower

| Melbourne Central Office Tower | |

|---|---|

| General information | |

| Type | Office |

| Location | Elizabeth Street, Melbourne CBD, Victoria, Australia |

| Height | |

| Antenna spire | 246 m (807 ft) |

| Roof | 210 m (690 ft) |

| Technical details | |

| Floor count | 57 |

The Melbourne Central Office Tower tops out at 210 metres (690 ft) with 57 storeys, 46 of which are for office use. Currently it is occupied by ME Bank replacing space previously tenanted by BP and Telstra.[55][56] Several Australian and Victorian Government departments and agencies maintain spaces in the tower including Creative Australia, the Department of Infrastructure, Transport, Regional Development, Communications and the Arts and the Victorian Energy & Water Ombudsman. Other tenants include Wilson Parking, Nordex and Pacific Basin Shipping Limited[57] The tower is owned by GPT Wholesale Office Fund[58] and the tower structure is approximately 210 metres (690 ft) tall. Including the two 54-metre (177 ft) communications masts that extend a further 35 metres (115 ft) above the apex, the tower is 246 metres (807 ft) tall.[59]

| List of tallest buildings in Australia | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Heights are to highest architectural element. | |||||

| List of tallest buildings in Melbourne | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Heights are to highest architectural element. | |||||

Coop's Shot Tower

The Coops Shot Tower was built in 1888 and used for making shot balls by dropping liquid lead off the top of the 50-metre (160 ft) high structure.[60] After last being used in 1961, the tower was retained after being heritage listed to become a focal point and symbol of Melbourne Central itself.

It is enclosed by an 80-metre (260 ft) high glass cone, built when the complex was constructed in 1991. It weighs 490 tonnes and has 924 glass panes. The cone is the largest of its kind in the world and was built in reference to the large dome of the adjacent State Library of Victoria.[16] The glass panes are cleaned by a specially designed mechanical system. Upon the centre's opening it was referred to as the "Magic Cone".[11]

The tower now contains the Shot Tower Museum and retail stores R.M. Williams, Supré and DJI[57]

The Marionette Watch

The watch, designed by Seiko, was given as a gift to the people of Melbourne. When it was unveiled together with the rest of the complex in 1991, the watch had a twelve and a half metre, two tonne chain. This is no longer attached as it was removed during the centre's refurbishment in 2002 and not replaced.[5]

Every hour, on the hour, a marionette display drops down from the bottom of the watch with Australian galahs, cockatoos and two minstrels performing Waltzing Matilda, under the watchful gaze of some koalas. The Seiko branding has since been removed.[61]

The Vertical Garden

A vertical garden was installed on the side of the Coop's Shot Tower as part of the Melbourne International Design Festival in July 2008. Pioneered by internationally renowned French artist and scientist, Patrick Blanc, the garden had no soil and was attached to the wall using PVC plastic.[62] However, the running cost proved expensive and in 2013 it was replaced with an advertising billboard.[63]

Retail

Melbourne Central currently has 276 retail shops and services. Its current two anchor tenants, Hoyts Cinemas and Coles, each occupy 7,710 square metres (83,000 sq ft) and 1,310 square metres (14,100 sq ft) of space respectively.[3]

Other key tenants include JB Hi-Fi, adidas, Sephora, JD Sports, Platypus Shoes, Country Road, R. M. Williams, Cotton On, Lego Certified Store, Macpac, Under Armour, Nike, Supré, MECCA, DJI and Calvin Klein.

A large portion of the centre is dedicated to food and beverage outlets. These are concentrated in two food courts and one covered outdoor walkway.[64] These are:

- Food court on the Lower Ground Floor

- ELLA on the Ground Floor near Elizabeth Street

- Dining Hall on Level 2

There is a multi-level glass footbridge across Lonsdale Street to Myer, with the layout of the centre allowing people to walk almost uninterrupted through some form of a shopping centre for over half of the city's width or 5 city blocks, from La Trobe street to Little Collins Street. This occurs via Melbourne Central which joins to Myer which in turn joins to David Jones over Bourke Street Mall. The glass footbridge was closed when Myer Melbourne vacated their Lonsdale store building. The footbridge re-opened in April 2014 when the Emporium Melbourne shopping centre opened.

Transport

The centre is integrated into the Melbourne Central railway station which operates metropolitan trains. Surrounding tram and bus stops also provide public transport access to the complex.

Yarra Trams operates thirteen services via Melbourne Central station, on Swanston, Elizabeth, and La Trobe Streets.

Swanston Street

: East Coburg – South Melbourne Beach[65]

: East Coburg – South Melbourne Beach[65] : Melbourne University – East Malvern[66]

: Melbourne University – East Malvern[66] : Melbourne University – Malvern[67]

: Melbourne University – Malvern[67] : Moreland – Glen Iris[68]

: Moreland – Glen Iris[68] : Melbourne University – Kew[69]

: Melbourne University – Kew[69] : Melbourne University – East Brighton[70]

: Melbourne University – East Brighton[70] : Melbourne University – Carnegie[71]

: Melbourne University – Carnegie[71] : Melbourne University – Camberwell[72]

: Melbourne University – Camberwell[72]

Elizabeth Street

: North Coburg – Flinders Street Station[73]

: North Coburg – Flinders Street Station[73] : West Maribyrnong – Flinders Street Station[74]

: West Maribyrnong – Flinders Street Station[74] : Airport West – Flinders Street Station[75]

: Airport West – Flinders Street Station[75]

La Trobe Street

Kinetic Melbourne operates four bus routes from Lonsdale Street (Melbourne Central side), under contract to Public Transport Victoria:

- 200 : to Bulleen[78]

- 207 : to Westfield Doncaster[79]

- 250 : to La Trobe University Bundoora campus[80]

- 251 : to Northland Shopping Centre[81]

Kinetic Melbourne operates thirteen bus routes from Lonsdale Street (Myer side), under contract to Public Transport Victoria:

- 250 : to Queen Street[80]

- 251 : to Queen Street[81]

- 302 : to Queen Street[82]

- 303 : to Queen Street[83]

- 304 : to King Street[84]

- 305 : to Spencer Street (Peak Hour only)[85]

- 309 : to Queen Street[86]

- 318 : to Spencer Street[87]

- 350 : to Queen Street[88]

- SmartBus 905 : to Spencer Street[89]

- SmartBus 906 : to Spencer Street[90]

- SmartBus 907 : to Spencer Street[91]

- SmartBus 908 : to Spencer Street (Peak Hour only)[92]

Kinetic Melbourne operates eleven bus routes from Swanston/Lonsdale Streets (QV), under contract to Public Transport Victoria:

- 302 : to Box Hill station[82]

- 303 : to Ringwood North[83]

- 304 : to Westfield Doncaster[84]

- 305 : to The Pines Shopping Centre (Peak Hour only)[85]

- 309 : to Donvale[86]

- 318 : to Deep Creek Reserve (Doncaster East)[87]

- 350 : to La Trobe University Bundoora campus[88]

- SmartBus 905 : to The Pines Shopping Centre[89]

- SmartBus 906 : to Warrandyte[90]

- SmartBus 907 : to Mitcham station[91]

- SmartBus 908 : to The Pines Shopping Centre (Peak Hour only)[92]

Gallery

-

Main entrance podium, corner La Trobe and Swanston Streets after re-development.

Main entrance podium, corner La Trobe and Swanston Streets after re-development. -

Melbourne Central, Lonsdale Street entrance, below bridge to Myer Melbourne.

Melbourne Central, Lonsdale Street entrance, below bridge to Myer Melbourne. -

Underneath the iconic glass cone

Underneath the iconic glass cone -

Food On 2 level Food Court

Food On 2 level Food Court -

Various floors in central area. (2010)

-

The Marionette Watch

-

Photo of the Basement level in Melbourne Central looking towards Melbourne Central Station after refurbishment.

Photo of the Basement level in Melbourne Central looking towards Melbourne Central Station after refurbishment.

See also

References

- ^ Building Profile Archived 21 November 2011 at the Wayback Machine, Melbourne Central Tower

- ^ a b Retail Archived 14 November 2012 at the Wayback Machine, GPT Group

- ^ a b c d e "GPT – 2023 ANNUAL RESULT PROPERTY COMPENDIUM" (PDF). GPT Group. Retrieved 27 May 2024.

- ^ "Melbourne Central > Stores > Centre Maps". Archived from the original on 24 January 2009. Retrieved 9 July 2011.

- ^ a b c d "Melbourne Central Heritage". Melbourne Central Shopping Centre. GPT. Retrieved 24 May 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Institute of Technology Bandung Java (September 1995). "Melbourne Central a Case Study in Post-Modern Urbanization". Archived from the original on 28 September 2011. Retrieved 26 September 2011.

- ^ a b c d Philip Hopkins (23 June 2010). "Retail revamp for Melbourne Central". The Age. Retrieved 26 September 2011.

- ^ "Annual metropolitan train station entries 2022-23". Data Vic. Department of Transport & Planning. Retrieved 24 May 2024.

- ^ McLoughlin, J. Brian (1992). Shaping Melbourne's future? town planning, the state, and civil society. London; New York: Cambridge University Press. p. 80. ISBN 9780521439749.

- ^ The largest redevelopment in Australia's history (Development brochure). Victorian Government. 1985.

- ^ a b c Ryan, Denise (8 September 1991). "Birth of a Department Store". The Age. p. 19. Retrieved 28 May 2024.

- ^ "Warehouse group". Victorian Heritage Database. Retrieved 10 February 2023.

- ^ Georgiev, Peter (April 1991). Architect - "The Speculative City: Melbourne Central". Royal Australian Institute of Architects (RIAA).

- ^ a b c "Melbourne Central Heritage - Melbourne Central Shopping Centre". www.melbournecentral.com.au. Retrieved 10 August 2025.

- ^ "Confident Daimaru opens huge store". Australian Financial Review. 10 September 1991. Retrieved 10 February 2023.

- ^ a b "MELBOURNE CENTRAL'S HERITAGE THE COOP'S SHOT TOWER IN 1889". www.melbournecentral.com.au. Melbourne Central. Retrieved 28 May 2024.

- ^ Corrigan, Majella (14 August 1991). "5 DISTINCTIVE 'WORLDS' FOR MELBOURNE CENTRAL". Australian Financial Review. Retrieved 10 August 2025.

- ^ Corrigan, Majella; Boylen, Louise (10 June 1993). "US TOY GIANT STAKES OUT A MELBOURNE CITY PRESENCE". Australian Financial Review. Retrieved 9 August 2025.

- ^ Barrymore, Karina (14 September 1993). "KUMAGAI AT RISK OF $1BN LOSS ON CITY RETAIL CENTRE". Australian Financial Review. Retrieved 9 August 2025.

- ^ "Mr Nice Guy". Daniel Bowen. 6 July 2010. Retrieved 11 August 2025.

- ^ Toy, Mitchell (16 November 2023). "Jackie Chan's cheesie Melbourne Mr Nice Guy action movie". Herald Sun. Retrieved 11 August 2025.

- ^ Barrymore, Karina (19 March 1999). "Besens get a jump in $370m bid for Central". Australian Financial Review. Retrieved 11 August 2025.

- ^ "Melbourne shopping centres: Owners of city's major retail destinations include some big names worth billions". www.realcommercial.com.au. Retrieved 11 August 2025.

- ^ a b c d Peter Semple (17 April 2002). "Melbourne Central set for makeover". The Age. Retrieved 26 September 2011.

- ^ "Daimaru to close Australian stores". The Japan Times. 26 September 2001. Retrieved 11 August 2025.

- ^ "Daimaru prepares for a last hurrah". The Age. 3 June 2002. Retrieved 11 August 2025.

- ^ a b c d Corrie Perkin (23 June 2002). "The refashioning of Melbourne Central". The Age. Retrieved 26 September 2011.

- ^ "Calm after the storm, as centre loses its anchor". The Age. 9 July 2002. Retrieved 11 August 2025.

- ^ Barrymore, Karina (12 April 2002). "Melbourne Central in $195m revamp". Australian Financial Review. Retrieved 11 August 2025.

- ^ "GPT announces major redevelopment at Melbourne Central". www.asx.com.au. Retrieved 11 August 2025.

- ^ "Melbourne Central renovation". The Age. 30 August 2005. Retrieved 29 May 2024.

- ^ "Melbourne Central Redevelopment / ARM Architecture". armarchitecture.com.au. Retrieved 12 August 2025.

- ^ Guthrie, Susannah (30 May 2023). "This is officially the busiest intersection in Melbourne". Drive. Drive.com.au. Retrieved 24 May 2024.

- ^ "Melbourne Central Station redevelopment, 2003 – Public Transport Users Association". Retrieved 11 August 2025.

- ^ Tivendale, Knowles. "CBD Pedestrian Congestion - Public Transport Access" (PDF). City of Melbourne. Tivendale Transport Consulting. Retrieved 24 May 2024.

- ^ "Melbourne Central set to prey on captive commuters". The Age. 4 November 2003. Retrieved 24 May 2024.

- ^ "Melbourne Central Closure Study Flawed, Say Users". Public Transport Users Association. Retrieved 24 May 2024.

- ^ "Ideas Above its Station". ArchitectureAU. Archived from the original on 28 May 2024. Retrieved 19 August 2025.

- ^ a b "Shopping centre to be 'lifestyle venue'". The Age. 31 August 2003. Retrieved 12 August 2025.

- ^ "Opening a world of difference". The Age. 16 May 2004. Retrieved 19 August 2025.

- ^ "Hoyts Melbourne Central in Melbourne, AU - Cinema Treasures". cinematreasures.org. Retrieved 12 August 2025.

- ^ "VHD". vhd.heritagecouncil.vic.gov.au. Retrieved 12 August 2025.

- ^ "Hoyts Cinema Centre in Melbourne, AU - Cinema Treasures". cinematreasures.org. Retrieved 12 August 2025.

- ^ Hopkins, Philip (22 June 2010). "Retail revamp for Melbourne Central". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 19 August 2025.

- ^ a b "Melbourne Central set for retail revamp". InvestSMART. 23 June 2010. Retrieved 29 May 2024.

- ^ "GPT Quarterly Update" (PDF). The GPT Group. March 2011.

- ^ "Melbourne Central opens vibrant new food precinct | IR News |". Inside Retail. Archived from the original on 1 October 2011. Retrieved 9 July 2011.

- ^ "The Uncarved Block". ArchitectureAU. Archived from the original on 15 August 2016. Retrieved 19 August 2025.

- ^ "Melbourne Central's new attractions". Meld Magazine. 2 September 2011. Retrieved 19 August 2025.

- ^ "GPT Annual Review 2011" (PDF). The GPT Group. Retrieved 19 August 2025.

- ^ "Strike Bowling Bar's new venue promoted with world's first social media powered flight". Campaign Brief. 26 April 2012. Retrieved 12 August 2025.

- ^ Bencic, Emily (28 June 2017). "JB Hi-Fi to open three more stores this year". Appliance Retailer. Retrieved 12 August 2025.

- ^ Bate, Weston (1994). Essential but unplanned: the story of Melbourne's lanes. Melbourne: State Library of Victoria. p. 16. ISBN 9780730635987.

- ^ Mahlab, Bobbi (27 August 1989). "Business body opposes bridge plan". The Age. Retrieved 24 May 2024.

- ^ "GPT secures ME Bank & Allianz - Australian Property Journal". Australian Property Journal. 14 July 2010. Retrieved 27 May 2024.

- ^ "The GPT Group > Announcements & Media Releases". Archived from the original on 30 September 2011. Retrieved 10 July 2011.

- ^ a b "Customer Directory". Melbourne Central Tower. Retrieved 27 May 2024.

- ^ "Melbourne Central Tower - the Owners". Archived from the original on 19 February 2011. Retrieved 10 July 2011.

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 March 2012. Retrieved 10 July 2011.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ Sides, Carol (2 February 1982). "Looking at the Melbourne many people do not know". The Age. p. 20. Retrieved 26 April 2011.

- ^ "Open House Melbourne: top things to book". Australian Design Review. Retrieved 29 May 2024.

- ^ Kinsey, Melanie (19 August 2009). "Raising the roots". Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 31 May 2024.

- ^ Paul, Mark. "Greenwalls – latest fashion or much more |". Garden Drum. Retrieved 31 May 2024.

- ^ "Centre Map - Melbourne Central". www.melbournecentral.com.au. Retrieved 31 May 2024.

- ^ "1 East Coburg - South Melbourne Beach". Public Transport Victoria.

- ^ "3-3a Melbourne University - East Malvern". Public Transport Victoria.

- ^ "5 Melbourne University - Malvern". Public Transport Victoria.

- ^ "6 Moreland - Glen Iris". Public Transport Victoria.

- ^ "16 Melbourne University - Kew via St Kilda Beach". Public Transport Victoria.

- ^ "64 Melbourne University - East Brighton". Public Transport Victoria.

- ^ "67 Melbourne University - Carnegie". Public Transport Victoria.

- ^ "72 Melbourne University - Camberwell". Public Transport Victoria.

- ^ "19 North Coburg - Flinders Street Station & City". Public Transport Victoria.

- ^ "57 West Maribyrnong - Flinders Street Station & City". Public Transport Victoria.

- ^ "59 Airport West - Flinders Street Station & City". Public Transport Victoria.

- ^ "30 St Vincents Plaza - Docklands via La Trobe St". Public Transport Victoria.

- ^ "35 City Circle (Free Tourist Tram)". Public Transport Victoria.

- ^ "200 City (Queen St) - Bulleen". Public Transport Victoria.

- ^ "207 City - Doncaster SC via Kew Junction". Public Transport Victoria.

- ^ a b "250 City (Queen St) - La Trobe University". Public Transport Victoria.

- ^ a b "251 City (Queen St) - Northland SC". Public Transport Victoria.

- ^ a b "302 City - Box Hill via Belmore Rd and Eastern Fwy". Public Transport Victoria.

- ^ a b "303 City - Ringwood North via Park Rd". Public Transport Victoria.

- ^ a b "304 City - Doncaster SC via Belmore Rd and Eastern Fwy". Public Transport Victoria.

- ^ a b "305 City - The Pines SC via Eastern Fwy". Public Transport Victoria.

- ^ a b "309 City - Donvale via Reynolds Rd". Public Transport Victoria.

- ^ a b "318 City - Deep Creek". Public Transport Victoria.

- ^ a b "350 City - La Trobe University via Eastern Fwy". Public Transport Victoria.

- ^ a b "905 City - The Pines SC via Eastern Fwy & Templestowe (SMARTBUS Service)". Public Transport Victoria.

- ^ a b "906 City - Warrandyte via The Pines SC (SMARTBUS service)". Public Transport Victoria.

- ^ a b "907 City - Mitcham via Doncaster Rd (SMARTBUS service)". Public Transport Victoria.

- ^ a b "908 City - The Pines SC via Eastern Fwy (SMARTBUS Service)". Public Transport Victoria.