Mary Karadja

Mary Karadja | |

|---|---|

.jpg) | |

| Born | Marie Louise Smith 12 March 1868 Stockholm, Sweden |

| Died | 7 September 1943 (aged 75) Locarno, Switzerland |

| Occupation(s) | Writer, spiritual medium |

| Spouse | |

| Children | 3, including Constantin Karadja |

| Father | Lars Olsson Smith |

| Relatives | Lucie Lagerbielke (sister) Aristide Caradja (in-law) |

| Signature | |

| |

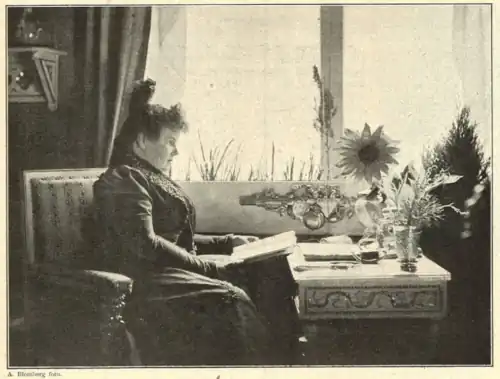

Marie Louise "Mary" Karadja (née Smith; 12 March 1868 – 7 September 1943) was a Swedish writer, spiritual medium and aristocrat, a central figure in Western esotericism during the Belle Époque. Born in Stockholm to the business magnate Lars Olsson Smith, she married Jean Karadja Pasha, an Ottoman diplomat, and gave him a son, the Romanian diplomat and scholar Constantin Karadja. She lived in various European countries, and published works in several languages—beginning with aphorisms in French. Her involvement with Kardecist spiritism dates to 1899, and was prompted by the deaths of an infant son and of her husband the prince. Under the influence of spiritism, Theosophy and neo-gnosticism, the princess produced spirit drawings and writings that she claimed was inspired and dictated to her spiritually. She was for a while a literary celebrity in her native country, and corresponded with August Strindberg; she was also heavily criticized for her claims by investigators such as Henry Morselli and Joseph McCabe, and was regular target of Birger Sjöberg's satirical articles.

In the 1910s, Karadja had become explicit in her criticism of Christianity, favoring the unification of faiths into one world religion; she outlined her interpretation of religious mysteries in various texts, including her 1912 play about Solomon, drawing in themes from Rosicrucianism and the Freemasonry, as well as from the Kabbalah. The princess was rebuked by Catholic activists such as Henri Delassus, who regarded her and her convictions as components of a destructive plot against the Christian faith. Switching to Nazi and generally antisemitic views during the interwar period, she financed various organisations that held those views, and founded the Christian Aryan Protection League. During the 1930s, when she was living mostly in Switzerland and networking with its National Front, she became noted for defending the The Protocols of the Elders of Zion as an authentic document; she also supported a prototype of the Madagascar Plan, calling for the mass deportation of European Jews.

Her own fortune greatly reduced by the Great Depression, Karadja endorsed monetary reform as proposed by Arthur Kitson. Her far-right convictions were at the center of public controversy in Switzerland, resulting in her being singled out as an agent of influence on behalf of Nazi Germany. They had also caused a rift with her sister, Lucie Lagerbielke, who supported far-left causes; Constantin, meanwhile, had become noted as a leading figure, and alleged sponsor, of a fascist movement in Bucharest—the Crusade of Romanianism. The princess died at the height of World War II, just as her son had come to oppose Nazism and had begun rescuing Jews from the Holocaust.

Early life and marriage

Of mixed Swedish and English descent,[1] Marie Louise Smith was born on 12 March 1868 in Stockholm. Her parents were Mary Louise Collin and wholesale merchant Lars Olsson Smith; she was their fourth and youngest child. Her mother was born as an illegitimate child to a fishwife but was later adopted by the royal Swedish court dentist.[2] Meanwhile, her father was involved in the social reform movement and had made his fortune selling alcoholic beverages. Later in life, he also served in the first chamber of the Swedish parliament.[2][3] She and her older sister Lucie were first educated at home by a governess, before being sent to finishing schools in France, Italy and Switzerland. Beginning from the age of nine, she spent the majority of her time abroad;[2] she was in Geneva from 1877 to 1884.[4]

During one of her return visits to Stockholm, she met Prince Jean Karadja Pasha, the Ottoman envoy to The Hague and Stockholm. At the age of nineteen, she married the significantly older Karadja in 1887 in two ceremonies: an Eastern Orthodox ceremony at a Russian church, and a Protestant ceremony at her parents' house. The prince was considerably older than she was.[2][5] Through her marriage, she received the title of princess,[6] also converting to Orthodoxy.[7] Columnist Frederick William Wile (the "Duchese de Belimere") reported in September 1898 that: "The young ladies in Stockholm have all heard their mothers tell how [the Pasha] fell desperately in love with a Swedish girl [...], married her and left for The Hague, where they lived in happiness and peace."[8]

Together, Mary and Jean had three children, born in The Hague between 1888 and 1892; however, one, Constantin Jean Etienne, died in infancy in December 1889.[7] Her second-born, baptized Constantin Jean Lars, was one-month old at the time—he grew up to become a Romanian-language historian and diplomat of the Romanian Kingdom.[7][9][10] In 1892, when her daughter Despina was born,[11] Karadja published her first written piece Étincelles, a collection of English and French aphorisms. Literary historian Christophe Premat suggests that, with her linguistic and stylistic choices, she may have been trying "become part of a French literary aphoristic tradition and to play a mediating role in literary circles", but also that the aphorisms may be seen as her earliest experiments in automatic writing.[4] Premat argues that they total number, 333, already evidences Karadja's esoteric interests, as a likely reference to the names of God.[12] The same author sees them as modeled on the Book of Job, and equally so on writings by Jean de La Bruyère and François de La Rochefoucauld; they were overall anti-romantic, or anti-lyrical, in evidencing "human folly".[13] Chroniclers at The Bookman viewed Étincelles as mainly humorous, "an amusing little volume of aphorisms. They are not all original nor all witty [...]. The object of the keenest satire is the amateur player of the piano, who is again and again the butt of the epigrams [sic]."[14]

For the next fifteen years, Karadja wrote poetry and plays that were performed on stage in Sweden and abroad.[2][11] Prince Jean died of a "cerebral congestion"[15] in 1894, after which Mary and her children split their time living in Copenhagen, London, and their castle in Bovigny, Belgium.[2] As Premat notes: "She already had a large fortune before even meeting her husband, which allowed her to live comfortably when she became a widow in 1894 with two children to support."[4] For a while in the mid-1890s, she was in Stockholm, attending Birger Mörner's salon alongside Verner von Heidenstam, Selma Lagerlöf and Hjalmar Söderberg.[16] She continued to move between her various properties, accompanied by her servant "Marie R."; in early 1896, she accused the latter of having stolen family items worth 100,000 Belgian francs, and her account was backed by the Belgian prosecutors called in to investigate.[17] Late that year, Karadja was considering a move to Scania, where she wished to purchase Osbyholm Castle.[18] Also then, she was celebrated by the writers at Idun for her taste in visual arts.[11]

Spiritualism and automatism

The death of her infant son and her husband ignited Karadja's interest in spirituality, and she initially integrated with a local tradition that led back to Emanuel Swedenborg.[11] In April 1899 in Stockholm, she attended her first séance. Afterwards, she went to London where she attended séances that had been advertised in newspapers. During the first of these London séances, medium Albert Vout Peters channelled her late husband and Fredrika Bremer, who spoke to her in Swedish.[19] She claimed that the prince had "conveyed a long message, the contents of which no one other than [he] could know."[20] She also reported that the protofeminist Bremer had ordered her to "'Help the Swedish woman!', something Mary Karadja then thought she would do through her spiritual activities."[21] From then, Karadja became increasingly interested in spiritualism and soon claimed to be a medium herself.[6] She then invited Vout Peters and other mediums to Stockholm;[22] a debate ensued when psychologist Axel Herrlin exposed several of them as frauds, pushing Karadja into a defensive position.[23]

Karadja's fascination with spiritualism and mediumship influenced much of her writing; she also produced spirit drawings, especially portraits (done "in a dark room, in which various people recognized long-dead figures").[20] She claimed that much of her literary output was dictated to her by spiritual beings: "[She] continued to write hundreds of verses, 'even very good verses'—without even once having to tweak the words in their order."[20] Such pieces include a poem, Mot ljuset ("Into the Light"), which she claimed appeared to her while praying at the graves of her husband and son in Bovigny, on the feast of Sânziene in 1899;[11] "[w]hether the ghost that now appears is identical with The Pasha, the reader is not told."[24] As she puts it: "I was told to provide myself there with paper and writing materials. [...] What followed was not written automatically but through inspiration."[19] An autobiography of someone who had experienced all of life's pleasures, and was left despondent, Mot ljuset reportedly sold over 4,000 copies within weeks of its publication—an unusually high number for Sweden in 1900.[25] As Söderberg reports, the publication made her "[o]ur country's most popular author".[26] He believed that the popularity was well deserved, but not to the point of making one believe that her lyrics were of supernatural origin.[27]

In October 1900, Karadja was in Berlin, the Imperial German capital, where she attended séances with Vout, the medium Anna Abend, and the newcomer Pekka Ervast, a Theosophist and amateur investigator.[28] The latter vouched for her and her colleagues, and was informed by Vout, apparently in a trance, that: "You will become the instrument that will unite all of Scandinavia into one single nation."[23] Late that year, the princess returned with her children to Sweden, spending the holidays in Rättvik.[29] Abend followed her to Stockholm, hosting "starling seances" in the Karadja home; before the end of 1901, while touring Copenhagen, Abend was publicly exposed as a fraud.[30]

By January 1902, Karadja, described in the international press as "leader of a spiritualistic cult", had been taken to court by her father, who wished to recover his loan of 38,220 Swedish kronor,[31] or more than 10,000 US dollars in 1900s currency.[32] Smith was reportedly upset "the Princess Karadja is spending much money in the interest of the propaganda of spiritism", instead of saving it for his grandchildren.[32] Karadja shared an interest in the paranormal with her older sister Lucie Lagerbielke, though the latter was initially very skeptical: "It seems that [Lucia] assisted the others Smiths in their later attempt to have Mary committed to a clinic, based on the beliefs she held."[21] Upon Lagerbielke's conversion, both attempted to join the Edelweiss Society but were rejected—despite Karadja's friendship with the society's leader Huldine Fock.[6][33] However, Lucie disapproved of some aspects of spiritualism that Karadja partook in, including mediumship as she considered it unethical to attempt to make contact with the dead and to meddle with forces beyond their comprehension, and considered it spiritual rot.[34]

In 1901, Karadja published several brochures. One was printed in Dutch as De Bovenzinnelijke waereld ("The Supersensible World"), detailing her experiences as a medium; it carried a preface by Hendrik Jan Schimmel, who argued that spiritualism was a legitimate subject of scientific inquiry.[35] Another one appeared in Swedish as Hoppets evangelium ("Gospel of Hope"),[36] and was republished in French as L'Évangile de l'espoir. Reviewers for La Fronde called "a very just critique of the aberrations to which men are being pushed by blind faith".[37] By that time, she was involved with Gabrielle Wiszniewska's "Universal Alliance of Women for Peace", as a "member-benefactor".[38] In 1902, Karadja, animal rights activist Lizzy Lind af Hageby and Anna Synnerdahl founded the Christian-Spiritualist publication XXe Seklet. It aimed to combat social issues by implementing Christian ideals in everyday life.[2] In that context, the princess' reputation was harmed by her association with Anna Rothe, whom rationalist Joseph McCabe describes as her "pet medium": "[Rothe] was secretly watched, and was caught bringing bouquets from her petticoats and oranges out of her ample bosom; and the spirits did not save her from a year in gaol."[39] Karadja herself was mocked by the humorist Birger "Päta" Sjöberg in a 1902 faux report: "Princess Karadja has managed to make a sweet milk cheese glide across a table during a séance. It is claimed, however, that it was very full of worms."[40] Other Sjöbergian texts ridiculed Karadja's belief in spirits ("[i]magine that here, in the air around us, Saint Erik, Sten Baner, Gustavus Adolphus [...] and still others all run around in very airy and transparent figures. If you think about it more closely, how many crimes of lèse-majesté are you not guilty of?") and provided a mock-reportage of her encounter with the orientalist Carlo Landberg.[41] The latter had been inspired by Karadja's success to write his own book of poems, displaying his own skepticism in regard to spiritual matters.[42]

Neo-gnosticism and charities

According to the occultist Oswald Wirth, in 1904 the princess claimed to have had an out-of-body experience that lasted three days in all, at the end of which she reported having been initiated into the Masonic mysteries.[43] As assessed by the fellow mystic Paul Sédir, her resulting beliefs were similar to the "doctrines of the primitive Rosy Cross."[44] By 1906, she was in contact with the celebrated playwright August Strindberg, inviting him to Bovigny.[36] The two engaged in a "presumably long" correspondence with each other, with Strindberg describing to her his own contacts with Theosophy.[45] By then, she had been observed by doctor Henry Morselli, who commented that she and other self-proclaimed mediums (such as Henry Steel Olcott and William Stainton Moses) had a "certain moral superiority", but were of low intellect and produced nothing of importance to society.[46]

In 1912 in Stockholm, Karadja founded a neo-gnostic society, with Hanna von Koch as her partner. After Karadja moved to London that same year, she also began the Universal Gnostic Alliance and later the White Cross Union.[2] Their stated purpose was to "circulate awareness of the great spiritual laws, in order to combat the forces of murder and desegregation that are poisoning today's atmosphere."[44] Karadja had initially claimed to be inspired by the Kabbalah tradition within Judaism,[20] and had taken an implicit stand against the persecution of Jews after the Dreyfus affair.[36] She completed a "mystical drama" and "esoteric poem" on the life and times of Solomon, published by Kegan Paul in 1912[44] and also performed as a play.[11] Sédir assessed that "[n]ot since the enormous works by Madame Blavatsky has any woman in esoteric history been capable of condensing such a great number of mysteries, and of accumulating such precise and clear erudition."[44] The poem and its explanatory notes were largely focused on the Queen of Sheba (whom Karadja called "Balkis"), which became the focus of attention from critics. According to an early note the Islamic Review, Karadja's views on femininity, as apparent in her description of Balkis, were consonant with the ideal status of women in Islam.[47] The author herself explained in some detail that she actually believed the queen to have been a demonic being (a daughter of Parī), who had stolen the Ark of the Covenant and taken it to Tigray.[48] Jewish writer Regina Miriam Bloch, who was involved with publishing the work, described Karadja as a "learned and brilliant Christian", noting that her provocative musings on Balkis were "diametrically opposed to the current orthodox notions".[49]

In tandem, the princess had made comments that were censured by the anti-Masonic publicist Henri Delassus. The latter described her as an enemy of Catholicism, noting that she had talked about all religions being the same, and had wanted their reunification; Delassus claimed to expose her association as one of several whereby "Satan [undermines] the Church of Jesus Christ to make his temple from the ruins."[50] Spiritist Léon Denis took his distance from Karadja, noting that "two lines" from her works could not be taken as proof that the movement itself was anti-Catholic.[51]

During the early stages of World War I, the princess was living at Bovigny. Following the German invasion of Belgium, she became president and honorary treasurer of the Commission for Relief, and allowed her castle to function as a field hospital. In late 1914, the government of Charles de Broqueville, which had relocated to Liège, sent her a letter of gratitude.[52] She later moved to London, in Onslow Square; she was still involved with the White Cross Union as secretary, having ceded the executive position to Lady Lumb. In early 1916, the two of them issued a call for "uplifting of spiritually strengthening literature", describing their society as the "spiritual" counterpart of the British Red Cross.[53] Karadja attempted to grant the Bovigny estate to her son, who refused it; Constantin was by then living in Sweden and Romania, where he had married a distant cousin, Marcella (daughter of the entomologist Aristide Caradja).[54]

Still living in London in the early 1920s, the princess became sympathetic toward the Neo-Jacobite Revival—on Royal Oak Day 1921, she presided upon a meeting of the Forget-me-not Royalist Club at the London Lyceum.[55] In November of that year, the Lyceum also hosted her "United Charities Fête", "in which many causes could benefit at one expense." Speaking guests included the Duchess of Abercorn, Lady Pamela Hambro, and Cecil Mary Wilson, wife of Field Marhsal Wilson.[56] By early 1924, she had grown pessimistic about the fate of humanity, predicting that: "Volcanic action will submerge one-third of the present-earth. In the final catastrophe, part of the American continent will be saved."[57]

Nazism and final years

Karadja maintained some of her interests after moving to Locarno in Switzerland in 1928,[5] advertising her new residence, the "Villa Lux", "as a spiritual broadcasting station" of the White Cross.[58] During Christmas 1929, she publicized her contempt for established religion, with an article that presented itself as a scientific interpretation of Christian mythology. The piece, which was decried by priest Félix Klein as a "solemn absurdity", proposed that the Immaculate Conception was a symbol of reincarnation, and conjectured that Saint Joseph was a Freemason.[59] In old age, Karadja became increasingly involved with antisemitic groups and Nazism. Her Villa Lux became a meeting place for far-right extremists.[2] Over the late 1920s, she became focused on solving the "territorial solution of the Jewish question" and founded the Christian Aryan Protection League, which aimed to deport European Jews to Madagascar.[5] In the 1930s, Karadja also cultivated a close friendship and letter correspondence with the head of the National Front in Bern District, Ubald von Roll.[60][61] In 1932, as vice president of the Bacon Society, the princess confessed to fears that her financial troubles and an "inflammation of the eyes" prevented her from ever visiting England. As she explained, her estate had been tied up in Swedish kronor, which had been devalued during the Great Depression.[62] Daughter Despina had continued to be active in North London, helping with charity work at Mildmay Mission and tending to impoverished families across the area.[63] She was additionally involved with the YWCA, where she gave speeches about the persecution of Christians in continental Europe.[64]

Mary Karadja anonymously published a document in France in 1934 defending the 1903 antisemitic text The Protocols of the Elders of Zion, which claimed there was a Jewish conspiracy to take over the world.[5] The following year, she returned with an article in La Voix des Nations of Brussels, where she declared herself opposed to both capitalism and Marxism, noting that the latter had introduced false definitions that only served the former. She also called out the "international bankers responsible for the current crisis", warning them that they had little time left to "save their skin"; though her text did not identify them by ethnicity, Le Patriote of Montreal, which reproduced her text, suggested that she had meant the international Jewry.[65] In 1936, Karadja had meetings with Arthur Kitson, who was fighting for "monetary reform".[66] Karadja financially supported other antisemitic groups across the world as well as using her connections to promote the cause. She was reluctant to engage in any underhand tactics used by those organisations, stating "I am the left hand, and do not want to know what the right hand does".[61]

Karadja's fascist views put her at odds with her sister Lucie, who was involved with Bolshevism and socialist movements.[34] Her Romanian son was active within the local far-right movement, allegedly sponsoring the Crusade of Romanianism;[67] he served as that group's vice president, and also briefly led his own "National Front" in 1935.[68] The princess herself was caught up in the Boris Tödtli affair of 1937–1938, whereby Swiss authorities clamped down on fascist networks. The writer C. A. Loosli, who had engaged in a civil trial against Roll's organisation, published photocopies of documents allegedly implicating Nazi Germany. According to the journalists who saw these, Karadja appeared to be well aware of the Front's business connections and sources of financing.[69] The authorities further alleged that she had been caught "gathering and distributing funds" that ultimately came from Germany.[70] The princess lived to see the first stages of World War II, from neutral Switzerland. As late as 1940, she was cited by the Kitsonian movement as one of the "monetary reform leaders" abroad.[71]

Princess Karadja died in Locarno on 7 September 1943, at the age of 75.[2][11] By then, Constantin was actively opposed to the German regime and, as a diplomat in Berlin, assisted Jews fleeing the Holocaust.[72] Blacklisted by the emerging Romanian communist regime in the late 1940s, and risking imprisonment, he died of "cerebral congestion" in 1950.[15] The last surviving of Mary's children was daughter Despina, who died in 1983.[11] Revisiting the "Päta" lampoons in 1945, journalist August Peterson added a footnote: "Our somewhat older readers will surely remember this lady [Mary Karadja] and give out a tiny smile".[73] In his 2022 overview, Premat observed that she had not been yet included in any study of Swedish literature, only being mentioned in essays about "occult literature in the service of a theosophical ideology."[4] One of Strindberg's letters to her was acquired in early 1983 by the Central University Library of Bucharest.[74]

References

- ^ Pippidi 1997, p. 133.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Nilsson, Ulrika (9 February 2021). "Marie Louise (Mary) Karadja". Svenskt kvinnobiografiskt lexikon. Retrieved 30 July 2025.

- ^ Premat 2022, pp. 92, 93.

- ^ a b c d Premat 2022, p. 92.

- ^ a b c d Voss, Julia (19 October 2022). Hilma Af Klint. University of Chicago Press. p. 280. ISBN 9780226689760.

- ^ a b c "Mary Karadja". The Collection of Mediumistic Art. Archived from the original on 15 October 2024. Retrieved 30 July 2025.

- ^ a b c Stănculescu 2010, p. 349.

- ^ Duchese de Belimere (1898-09-18). "Queer Springs of Gentility". The Mexican Herald. p. 11.

- ^ Filitti 2000.

- ^ Pippidi 1997.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Stănculescu 2010, p. 350.

- ^ Premat 2022, pp. 105–106.

- ^ Premat 2022, pp. 97–98, 102–104, 106.

- ^ "The New Books of the Month. Miscellaneous". The Bookman. II (8): 64. 1892.

- ^ a b Pippidi 1997, p. 134.

- ^ Söderberg 1921, p. 159.

- ^ "Nouvelles Diverses. Vol de 100,000 francs. Descente du parquet à Schaerbeek". Journal de Bruges (in French). 1896-05-12. p. 3.

- ^ "News from Scandinavia. Interesting Items from Sweden, Norway and Denmark". The Fort Dodge Messenger. 1896-10-09. p. 4.

- ^ a b M. T. (1900). "Works by the Princess Karadja". Light. A Journal of Psychical, Occult, and Mystical Research. XX (1033): 513.

- ^ a b c d "Aus aller Welt. Eine Fürstin als Medium". Grazer Tagblatt (in German). 1902-04-25. p. 9.

- ^ a b Faxneld, Per (2020). "Kvinnligt ledarskap inom svensk spiritism runt år 1900". In Sorgenfrei, Simon; Thurfjell, David (eds.). Kvinnligt religiöst ledarskap. En vänbok till Gunilla Gunner (Södertörn Studies on Religion 10) (in Swedish). Södertörns högskola. p. 130. ISBN 978-91-89109-03-2.

- ^ Bogdan, Henrik; Hammer, Olav, eds. (2016). Western Esotericism in Scandinavia. Brill. p. 528. ISBN 9789004325968.

- ^ a b Gullman 2022, pp. 94–95.

- ^ Söderberg 1921, p. 316.

- ^ Törnebohm, A. E. (1900). "Échos et nouvelles. Le Spiritisme en Suède". Le Progès Spirite (in French). 6 (10): 78–79.

- ^ Söderberg 1921, p. 315.

- ^ Söderberg 1921, pp. 315–319.

- ^ Gullman 2022, pp. 93–95.

- ^ "News from Scandinavia. Interesting Items from Sweden, Norway and Denmark". The Evening Messenger. 1901-01-16. p. 6.

- ^ "News of Scandinavia. Recent Occurrences of Interest in Sweden, Norway and Denmark". The Zumbrota News. 1901-12-13. p. 1.

- ^ "Scandia. Notes". Iowa County Democrat. 1902-01-23. p. 7.

- ^ a b "News from Scandinavia. Interesting Notes from Across the Ocean. Happenings in the Fatherland". The Stillwater Messenger. 1902-02-08. p. 4.

- ^ "LUCIE LAGERBIELKE". Collection of Mediumistic Art. Archived from the original on 14 January 2025. Retrieved 30 July 2025.

- ^ a b Nilsson, Ulrika (9 February 2021). "Lucie Lagerbielke". Svenskt kvinnobiografiskt lexikon. Archived from the original on 22 April 2025. Retrieved 30 July 2025.

- ^ "Nieuwe uitgaven". Algemeen Handelsblad (in Dutch). 1901-11-03. p. 6.

- ^ a b c Premat 2022, p. 105.

- ^ "Bibliographie". La Fronde. 1902-02-28. p. 4.

- ^ "Membres bienfaiteurs qui versent une cotisation annuelle de 20 francs" (Document). Paris: Alliance Universelle des Femmes pour la Paix. 1900. p. 4.

- ^ McCabe, Joseph (1920). Is Spiritualism Based on a Fraud?. Watts & Co. p. 89.

- ^ Peterson 1945, p. 52.

- ^ Peterson 1945, pp. 52–55.

- ^ Söderberg 1921, pp. 318–319.

- ^ Fomalhaut, N. (1913). "Index documentaire. Compte rendu des sciences occultes. Franc-Maçonnerie". Revue Internationale des Sociétés Secrètes (in French). III (1): 113.

- ^ a b c d Sédir (1912). "Bibliographie. Le roi Solomon, drame mystique". L'Initiation (in French). 95 (9): 288.

- ^ Stănculescu 2010, p. 348, 350–351.

- ^ de Vesme, C. (1908). "Le nouvel ouvrage du professeur H. Morselli: Psychologie et Spiritisme". Annales des Sciences Psychiques (in French). 18 (22–24): 343.

- ^ "Review. 'King Solomon' and Woman". Islamic Review. I (3): 40–42. 1913.

- ^ Bloch 1921, pp. 733–734.

- ^ Bloch 1921, p. 733.

- ^ Delassus, Henri (1910). La conjuration antichrétienne. Le temple maçonnique voulant s'élever sur les ruines de l'Église catholique (in French). Vol. 2. Desclée, De Brouwer et Cie. pp. 747–748.

- ^ Denis, Léon (1911). "Le Spiritisme et ses détracteurs catholiques, réponse d'un vieux spirite à un docteur ès-lettres de Lyon (Suite)". La Vie Future. Revue Psychologique de l'Afrique du Nord (in French). 6 (61): 236.

- ^ "Princess Karadja". The Daily Star-Mirror. 1914-12-18. p. 4.

- ^ "Casual Comment. A Call for Cheering Literature". The Dial. LX (714): 269. 1916.

- ^ Filitti 2000, p. 43.

- ^ "Royal Oak Day". The Jacobite. The Only Jacobite Paper in New Zealand. I (8): 31. 1921.

- ^ A. E. L. (1921-11-19). "The World of Women". The Illustrated London News. p. 698.

- ^ "A Page about People. The Gloomy Princess". The London Evening Advertiser. 1924-02-02. p. 8.

- ^ "White Cross Union". The Seer. A Monthly Review of Astrology and of the Psychic and Occult Sciences. III (5): 247. 1931.

- ^ Klein, Félix (1929-12-31). "Un article traduit dans dix langues". La Croix (in French). p. 5.

- ^ Hagemeister, Michael (2021). The Perennial Conspiracy Theory Reflections on the History of The Protocols of the Elders of Zion. Taylor & Francis. p. 70. ISBN 9781000532708.

- ^ a b Ben-Itto, Hadassa (2005). The Lie That Wouldn't Die: The Protocols of the Elders of Zion. Vallentine Mitchell. pp. 110–111. ISBN 9780853036029.

- ^ Karadja, Mary (1932). "A Sad Valedictory from Locarno". Baconiana. XXI (79): 59.

- ^ Olafsson, Ingibjörg (1933). "Vainiot vaalenevat elonkorjuuta varten". Kotia Kohti (in Finnish). XXXII (2): 19.

- ^ "Persecution in Europe. Princess and Enemies of Christians". The Glasgow Herald. 1936-02-19. p. 9.

- ^ "Capital et capitalisme. Un article signé par la Princesse Karadja". Le Patriote (in French). 1935-12-05. p. 2.

- ^ "Arthur Kitson's Monetary Battle". Honest Money Year Book and Directory: 50. 1940.

- ^ Ornea, Zigu (1995). Anii treizeci. Extrema dreaptă românească (in Romanian). Editura Fundației Culturale Române. p. 306. ISBN 973-9155-43-X.

- ^ Cseresnyés, Sándor (1935-11-04). "Társadalmi erőcsoportosulások Romániában: Seregszemle a jobboldali fronton. Zsidóprogram megalkuvással". Brassói Lapok (in Hungarian). p. 12.

- ^ "L'espionnage allemand en Suisse". Courrier de Genève (in French). 1937-10-06. p. 2.

- ^ "Le procès de Berne. De nouvelles révélations sont fournies sur l'action du nazisme en Europe occidentale". Le Midi Socialiste (in French). 1938-04-07. p. 2.

- ^ "Names of Monetary Reform Leaders". Honest Money Year Book and Directory: 192. 1940.

- ^ Trașcă, Ottmar; Obiziuc, Stelian (2010). "Diplomatul Constantin I. Karadja și situația evreilor români din statele controlate/ocupate de cel de-al III-lea Reich, 1941–1944". Historica Yearbook (in Romanian): 109–141.

- ^ Peterson 1945, p. 53.

- ^ "Biblioteca Centrală Universitară din București s-a îmbogățit cu noi lucrări". Scînteia Tineretului (in Romanian). 1983-04-28. p. 4.

Sources

- Bloch, Regina Miriam (1921-07-23). "Sidelights on the Queen of Sheba". The Reform Advocate. pp. 732–734.

- Filitti, Georgeta (2000). "Constantin I. Karadja (1889–1950)". Arhiva Genealogică (in Romanian). VII (1–4): 43–46.

- Gullman, Erik (2022). Totuus on korkein hyve. Pekka Ervastin elämäkerta (in Finnish). Ruusu-Ristin Kirjallisuusseura ry. ISBN 978-952-9603-63-3.

- Peterson, August (1945). "Strövtåg i »Frän». II. Reportaget" (PDF). Vänersborgs Söners Gilles Årsskrift (in Swedish): 31–61. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 July 2020.

- Pippidi, Andrei (1997). "Comptes rendus. Georgeta Penelea-Filitti, Lia Brad-Chisacof, Comorile unei arhive". Revue des Études Sud-Est Européennes (in French). XXXV (1–2): 133–135.

- Premat, Christophe (2022). "Étincelles ou les aphorismes français de Mary Karadja". Revue Nordique des Études Francophones (in French). 5 (1): 91–108.

- Söderberg, Hjalmar (1921). Skrifter (in Swedish). Vol. 9. Bonniers.

- Stănculescu, Ileana (2010). "O scrisoare a lui August Strindberg" (PDF). Acta Mvsei Porolissensis (in Romanian). XXXI–XXXII: 347–354. Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 April 2025.