Mara Branković

| Mara Branković | |

|---|---|

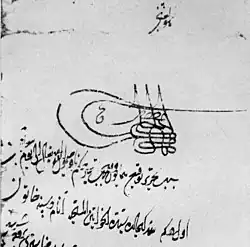

.jpg) Illustration from 1429 | |

| Valide Hatun of the Ottoman Empire | |

| Tenure | 1457 – 3 May 1481 |

| Predecessor | Emine Hatun |

| Successor | Gülbahar Hatun |

| Born | c. 1420 Vučitrn, Serbian Despotate |

| Died | 14 September 1487 (aged 66–67) Constantinople, Ottoman Empire |

| Spouse | |

| House | House of Branković House of Osman |

| Father | Đurađ Branković |

| Mother | Irene Kantakouzene |

| Religion | Orthodox Christian |

Mara Branković (Serbian Cyrillic: Мара Бранковић; c. 1420 – 14 September 1487), or Mara Despina Hatun, in Europe also known as Amerissa, Sultana Maria or Sultanina, was a Serbian Christian Orthodox Hatun or sultana of the Ottoman Empire.

She became a leading member of the pro-Ottoman party in the Balkans and one of the most powerful women of the 15th century.

Born a Serbian princess, daughter of Serbian despot Đurađ Branković and Eirene Kantakouzene. She married Sultan Murad II. and was a stepmother of Mehmed II the Conqueror. She became a important figure in her stepson's government where she was his trusted advisor, acting as a diplomatic figure between the Ottoman and European powers. Her major role was as a diplomat for the empire with missions to Venice and Hungary. Due to her influence ambassadors from Venice and Ragusa frequently seek her counsel.

Known as the "mistress of the Christian noblewomen," she promoted cooperation during periods of significant tension between Europe and the Ottoman Empire. Despite her involvement in Ottoman politics, she remained devoted to her Christian faith, influencing the selection of Patriarchs of Constantinople and supporting Christian communities under Ottoman rule.

Family

Mara Branković descended from four South-East European dynasties: the Brankovići, Nemanjići, Kantakuzēnoi and Palaiologoi. She was born between 1417 and 1420, possibly in 1418, and was the third child of the Serbian despot George Branković and of Eirēnē Palaiologina Kantakuzēnē. [1][2]

Mara and her relations are named in "Dell'Imperadori Constantinopolitani", a manuscript held at the Vatican Library. The document is also known as the "Massarelli manuscript" because it was found in the papers of Angelo Massarelli (1510–1566)[3] the general secretary of the Council of Trent.[4]

The Massarelli manuscript names her as one of two daughters of Đurađ Branković and Eirene Kantakouzene. The other sister is Catherine (Kantakuzina Katarina Branković or Katarina of Celje), who was married to Ulrich II, Count of Celje (1406–1456).

On 11 September 1429, Đurađ made a donation to Esphigmenou Monastery at Mount Athos. The charter for the document names his wife Irene and five children. The Masarelli manuscript also names the same five children of Đurađ and Eirene. Other genealogies mention a sixth child, Todor Branković. He could be a child who died young and is thus not listed with his siblings.

The oldest sibling listed in the Massarelli document is Grgur Branković.

Mara is mentioned as the second child in the manuscript. Next are listed Stefan Branković. The last sibling mentioned is Lazar Branković, the youngest of the five.

Marriage

After 1428–following her engagement to the Ottoman Sultan Murad II–she emerges from anonymity. In 1433 her father George Branković was still preparing her dowry, but in August/September 1436 the marriage finally took place in Adrianople (Edirne). The betrothal was an attempt to prevent an invasion of Serbia from the Ottoman Empire, though periodic Ottoman raids continued. On 4 September 1435, the marriage took place at Edirne. Her dowry included the districts of Dubočica and Toplica.[5] Mara apparently "did not sleep with" her husband.[6]

Stepmother to the Sultan

During her first stay in the Ottoman Empire, between 1436 and 1451, she got to know her stepson Mehmed II, thus establishing the framework for her later role in South East Europe. The Ottoman Sultan regarded the Serbian princess as his “surrogate mother” after the death of his physical mother in 1449 [1][2] Evidence points at a cooperation between Mehmed, Mara and Skanderbeg in the wake of the latter’s vendetta against Ali, Murad’s most preferred son. [1][2]

In 1451 Murad II died and Mara was released from the harem. Mehmed II allowed her to return to Serbia. [7] Mehmed II used their connection to claim Serbia in 1454 [8] when her father sought an alliance with the Hungarians and became inconstant with this tribute. Ottoman Serbia had been had been a vassal state intermittently since the Battle of Kosovo in 1389.

Serbian invasion

While Mara was back in Serbia, Mehmed II claimed lands in Serbia, using their connection, the inconstant tributes from her father and an alliance with the Hungarians. In 1454 Brankovic refused to give some Serbian castles that had belonged to the Ottomans[9] and an army led by Mehmed II set out from Edirne towards Serbia. In 1456, Mehmed decides to capture the city of Belgrade, which had been ceded to the Kingdom of Hungary by Mara’s father in 1427.

Shortly before the end of the year 1456, roughly 5 months after the Siege of Belgrade, the 79 year old Branković died causing a succession conflict. The oldest brother, Grgur Branković, and Stephan had been blinded after their rebellion against Mara’s husband, Murad II in 1441, [10][11] so the youngest, Lazar Branković , had been declared heir. Mara supported her elder brother Grgur, in the succession dispute after her father’s death.

Mara returned to the Ottoman Empire in 1457. Some sources point that she might have been exiled by Lazar. [12]

Lazar died soon afterwards, and his successor Stefan Branković was ousted from power in March 1459. The chaotic situation created an opportunity for the Ottoman government[13][14] Mehmed personally led an army against the Serbian capital,[15] capturing Smederevo on the 20th of June 1459[16] ending the existence of the Serbian Despotate.[17]

Political life

Mara joined the court of her stepson Mehmed II in 1457 and functioned as a trusted advisor and ambassador. Mara, as an Orthodox Christian Hatun was an intermediary between "the sublime Porte" and Europe. [18]

Mara Despina Hatun, a Christian widow of Murad II, remained in the imperial court and acted as a trusted intermediary between the Porte and Christian Europe.[18]

After the unsuccessful Battle of Vaslui (Moldavia, 1475), Mara remarked that the battle was the worst defeat for the Ottoman Empire.[1]

Jezevo state as unofficial Foreign Office of the Empire

Sultana Mara maintained a presence at court but was also offered her own estate at "Ježevo". Likely Ježevo might be the modern settlement of Dafni near Serres.[19] When Mehmed became sultan, she often provided him with advice.[20] Her court at Ježevo included exiled Serbian nobles as her sister "Cantacuzina" in 1469 .[21] Historian Donald Nicol described Mara's estate near Mount Athos as an "unofficial foreign office," where she maintained contact with various European powers, including Ragusa (present day Dubrovnik) and Venice. [2]

Ambassador to Venetian Republic

Sultana Mara served as a de facto ambassador and intermediary for the Ottoman Empire during several mid-15th-century conflicts with European powers. Born a Serbian princess, she leveraged her Christian heritage and familial ties to forge temporary truces, negotiate trade terms, and defuse military confrontations between the sultans she served and rival courts. Dispatched to Venice during periods of rising tension over Dalmatian and Aegean trade routes, Mara acted as intermediary between Mehmed and the Republic of Venice during the first Ottoman–Venetian War (1463–1479). In 1471, Branković personally accompanied a Venetian ambassador to the Porte for negotiations with the Sultan. She secured concessions on grain shipments and merchant protections in exchange for Ottoman non-interference in Venetian holdings.[1][2]

Diplomatic missions to Hungary

Sultana Mara acted as negotiator with the Kingdom of Hungary. She led talks at Buda aimed at forestalling a Hungarian Papal alliance against Constantinople. [1][2]

Persuaded King Matthias Corvinus’s court to adopt a policy of neutrality, buying time for Ottoman consolidation in the Balkans.

Intermediary for Ragusan (Dubrovnik) Relations

Mara oversaw tribute payment agreements that preserved Ragusa’s autonomous trading status. She zcted as the principal contact for Ragusan envoys seeking safe conduct passes and dispute resolution. [1]

Advisor and Host to Foreign Ambassadors

Mara not also kept an informal foreign office in her lands in Jezevo, but maintained a salon in Constantinople where Venetian, Ragusan, and Hungarian diplomats sought her counsel. Sultana Mara used her network of Christian noblewomen to relay intelligence and temper hard line positions on both sides. [1]

Orthodox Christian Patreon

Mara retained her influence over the appointment of leaders of the Orthodox Church, and remained influential during the reign of Mehmed's successor, Bayezid II. The monks of Rila monastery begged her to have the remains of John of Rila transferred to Rila monastery from Veliko Tarnovo, and thanks to her their wish was fulfilled in 1469. Because of her influence, special privileges were offered to the Greek Orthodox Christians of Jerusalem, later extended to the community of Athos Monastery.[22]

Impact and Legacy

Through these missions, Mara helped stabilize Ottoman frontiers against Western coalitions, ensured the flow of critical supplies into besieged territories, and fostered a pragmatic modus vivendi that delayed major European crusades. Her unique position as a Christian sultana enabled channels of communication otherwise closed to Muslim emissaries, making her one of the most effective brokers of peace and commerce in her era. [1]

Ancestry

| Ancestors of Mara Branković | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Popular culture

- In 2005, Turkish artist Can Atilla realized the musical composition Mara Despina.[25]

- Portrayed by İdil Fırat in series Mehmed: Bir Cihan Fatihi (2018).

- Portrayed by Ebru Özkan in film Türkler Geliyor: Adaletin Kılıcı (2020).

- The character of Mara Hatun is fictionalized and portrayed by Tuba Büyüküstün in the Netflix original historical docudrama Rise of Empires: Ottoman (2020).[26][27] She is shown as someone who was brought from Serbia, who married Murad II for political reasons, and who supported Mehmed the Conqueror and influenced him.[26]

- Portrayed by Larissa Lara Türközer in series Kızılelma: Bir Fetih Öyküsü (2023).[28]

- The coast between Salonica and Kassandra peninsula has been named "Kalamarija" after her – "Mary the Good".

- In the Turkish series Mehmed: Sultan of Conquests, Mara Hatun is played by Turkish actress Tuba Ünsal.

- In the Hungarian-Austrian series Rise of the Raven, she is portrayed as John Hunyadi’s first love by Hungarian actress Franciska Törőcsik.

See also

- Jefimija

- Princess Milica of Serbia

- Saint Angelina of Serbia

- Olivera Lazarević (Olivera Despina Hatun)

- Jelena Balšić

- Saint Helen of Serbia

- Simonida

- Maria Angelina Doukaina Palaiologina

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h Beydilli, Kemal (2017). "II. Murad'ın Eşi Sırp Prensesi Mara Brankoviç (1418–1487)". Osmanlı Araştırmaları / The Journal of Ottoman Studies (in Turkish). XLIX. İstanbul: 29 Mayıs Üniversitesi: 383–412. Retrieved 18 August 2025.

- ^ a b c d e f Popović, Mihailo St. (2012). Mara Branković: Eine Frau zwischen dem christlichen und dem islamischen Kulturkreis im 15. Jahrhundert (in German). Wiesbaden: Verlag Franz Philipp Rutzen. p. 238.

- ^ "Tony Hoskins, "Anglocentric medieval genealogy"". Archived from the original on 16 July 2011. Retrieved 4 July 2008.

- ^ "The Archives: the past & the present", section "The Council of Trent" Archived 3 October 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Fine, John V. A.; Fine, John Van Antwerp (1994). The Late Medieval Balkans: A Critical Survey from the Late Twelfth Century to the Ottoman Conquest. University of Michigan Press. p. 530. ISBN 978-0-472-08260-5.

- ^ Burbank, Jane (2010). Empires in world history : power and the politics of difference. Frederick Cooper. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press. p. 134. ISBN 978-0-691-12708-8. OCLC 436358445.

- ^ Sphrantzes, George (1980). The Fall of the Byzantine Empire: A Chronicle. Translated by Marios Philippides. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press. pp. 162–165. ISBN 9780870232902. Retrieved 19 August 2025.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: checksum (help) - ^ Elizabeth A. Zachariadou, Romania and the Turks Pt. XIII p. 837-840, "First Serbian Campaigns of Mehemmed II (1454-1455)"

- ^ Uzunçarşılı, İsmail Hakkı (2019). Osmanlı Tarihi Cilt II [History of the Ottomans Volume II] (in Turkish). Türk Tarih Kurumu. pp. 13–18. ISBN 9789751600127.

- ^ umetnosti, Srpska akademija nauka i (1929). Godišnjak - Srpska akademija nauka i umetnosti, Belgrad. Srpska akademija nauk i umetnosti. p. 286.

- ^ Новаковић, Стојан (1972). Из српске историjе. Matica srpska. p. 201.

.. и како их је 8. маја ослепио, а потом како је јуна те године Хадом-паша узео Ново Брдо и све српске градове.

- ^ Fine, John Van Antwerp Jr. The Late Medieval Balkans: A Critical Survey from the Late Twelfth Century to the Ottoman Conquest. University of Michigan Press, 1987, p. 242.

- ^ Uzunçarşılı 2019, p. 20.

- ^ Tansel 1953, p. 130.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

:10was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ "SEMENDİRE". TDV İslâm Ansiklopedisi (in Turkish). Retrieved 14 September 2024.

- ^ Miller, William (1896). The Balkans: Roumania, Bulgaria, Servia, and Montenegro. London: G.P. Putnam's Sons. ISBN 978-0836999655. Archived from the original on 29 April 2016. Retrieved 8 February 2011.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ^ a b Goffman, Daniel (2002). The Ottoman Empire and Early Modern Europe. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521459082.

- ^ Nicol, Donald M. (13 July 1996). The Byzantine Lady: Ten Portraits, 1250-1500. Cambridge University Press. pp. 115, 119. ISBN 978-0-521-57623-9.

- ^ Nicol, Donald M. (13 July 1996). The Byzantine Lady: Ten Portraits, 1250-1500. Cambridge University Press. p. 116. ISBN 978-0-521-57623-9.

- ^ Nicol, Donald M. (13 July 1996). The Byzantine Lady: Ten Portraits, 1250-1500. Cambridge University Press. p. 118. ISBN 978-0-521-57623-9.

- ^ Nicol, Donald M. (13 July 1996). The Byzantine Lady: Ten Portraits, 1250-1500. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-57623-9.

- ^ Brook, Lindsay L. (1989). "The Problematic Ascent of Eirene Kantakouzene Brankovič". Studies in Genealogy and Family History in Tribute to Charles Evans on the Occasion of His Eightieth Birthday. Salt Lake City, Utah : Association for the Promotion of Scholarship in Genealogy. p. 5.

- ^ Williams, Kelsey Jackson (2006). "A Genealogy of the Grand Komnenoi of Trebizond" (PDF). Foundations. 2 (3): 171–189. Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 June 2019.

- ^ Mara Despina by Can Atilla

- ^ a b "Netflix docudrama reveals great defense of Byzantium, the small conquest of Ottoman Empire". Daily Sabah. 8 April 2020.

- ^ "Rise of Empires: Ottoman ne zaman başlayacak? Rise of Empires: Ottoman oyuncuları". Hürriyet. 12 December 2019.

- ^ "Kızılelma: Bir Fetih Öyküsü". 11 May 2023.

Further reading

- Fotić, Aleksandar (2000). "Despina Mara Branković and Chilandar: Between the Desired and the Possible". Осам векова Хиландара: Историја, духовни живот, књижевност, уметност и архитектура. Београд: САНУ. pp. 93–100.

- Popović, Mihailo St. (2010). Mara Branković: Еine Frau zwischen dem christlichen und dem islamischen Kulturkreise im 15. Jahrhundert. Wiesbaden: Franz Philipp Rutzen.