Mani Peninsula

The Mani Peninsula (Greek: Μάνη, romanized: Mánē), known historically as Maina or Maïna (Greek: Μαΐνη), is a geographical and cultural region of southern Greece. The Mani is the central of three peninsulas that extend southward from the Peloponnese into the Mediterranean Sea. The Laconian Gulf and the peninsula of Epidaurus Limera[a] are to the east; the Messenian Gulf and peninsula of Messenia are to the west. It terminates at Cape Matapan (called Tainaron by the Ancient Greeks), the southernmost point of continental Greece.

Administration of the peninsula is now split between modern Laconia (East Mani) and Messenia (West Mani). In ancient times all of Mani was considered part of Laconia, a region dominated by the powerful city-state, or polis, of Sparta.

The geographic and cultural region is frequently referred to in English-language sources as "the Mani", "the Mani Peninsula", or simply "Mani". These are long-used conventional names for the area that overlap with—but are semantically distinct from—the names of its two constituent municipalities of East Mani and West Mani, both established in 2011 following a nationwide reform.

The Mani Peninsula is the southern extension of the Taygetus mountain range. It is about 28 miles (45 km) long with a rocky, rugged, interior bordered by scenic coastlines. Cities of the Mani Peninsula include Areopoli in the northwest and Gytheio (ancient Gythion or Gythium) in the northeast.

The Mani Peninsula, now designated a historical district, was once known as Maina Polypyrgos ("Many-Towered Maina") for the numerous tower-houses built by locals who engaged in piracy, by raiding coastal shipping. Notable sites in Mani include the ruins of the ancient Temple of Poseidon at Cape Matapan and the Diros Caves with their prehistoric remains near Pyrgos Dirou outside Gytheio. The peninsula also played a key role in the Greek War of Independence that began in 1821.[1]

The inhabitants of Mani have traditionally been called the Maniots (Greek: Mανιάτες, romanized: Maniátes). They claim descent from ancient Spartans and refugees of the early Roman period and maintain a unique heritage among the regional subcultures of their fellow Greeks.

Etymology

There is no agreement on the origin of the word "Mani". The region's medieval name was Maini, however this is itself of uncertain origin. Two early 10th-century Byzantine emperors refer to the region by the name "Maini" in their writing. It was first mentioned in the Tactica of Emperor Leo VI the Wise (c. 900), and was mentioned again in the De Administrando Imperio of Emperor Constantine VII (r. 913–959). In 1205, the French established a Crusader state on the Peloponnese in the aftermath of the sack of Constantinople. They built a castle on the Mani in 1250 and called it the Grand Magne, presumably naming it after the region. [2][3] Still, folk traditions claim that the Mani is named for the "Frankish"[b] castle of Grand Magne and not the reverse.

Geography

Regional divisions

Mani has traditionally been divided into three regions:

- Exo Mani (Έξω Μάνη) or Outer Mani to the northwest, corresponding to the southernmost area of modern West Mani;

- Kato Mani (Κάτω Μάνη) or Lower Mani to the east, corresponding to part of modern East Mani;

- Mesa Mani (Μέσα Μάνη) or Inner Mani to the southwest, also corresponding to part of East Mani.

The island of Cranae is located just off the coast of Gytheio in Lower Mani. A causeway linking the island to the mainland was built in 1898.

Climate

The Mani Peninsula, like much of southern Greece, has a hot-summer Mediterranean climate (Köppen climate classification Csa).[4] The Messenian, or Outer, Mani receives somewhat more rainfall than the Laconian, or Inner and Lower, Mani (see: rain shadow) and as a consequence is more agriculturally productive. Locals call the Messenian Mani aposkiaderi, "shady" and the Laconian prosiliaki, "sunny". [5]

Transport

Because its terrain is mountainous and not easily accessible, many Mani villages could be reached only by sea until relatively recent times. Today, a narrow and winding road traverses the perimeter, linking Mani with the mainland through Kardamyli and Areopoli on the west coast to Cape Matapan in the south and Gytheio in the northeast. Another road connects Tripoli in the central Peloponnese to Gerolimenas near Cape Matapan; public buses of the Piraeus—Mani line use this route. Greek National Road 39 (Greek: Εθνική Οδός 39, EO39) connects Tripoli with Gytheio via Sparta.[6]

The E4 European long distance walking path traverses the Taygetus to a land terminus in Gytheio, connecting the Peloponnese to Spain. The path continues to Crete by ferry crossing.

Administration

The peninsula is divided into the administrative municipalities of East Mani (Ανατολική Μάνη, Anatolikí Máni) and West Mani (Δυτική Μάνη, Dytikí Máni), in the modern regional units of Laconia and Messenia, respectively.

Cities and settlements

Modern

- Agios Nikolaos

- Areopoli

- Gerolimenas

- Gytheio

- Kampos

- Kardamyli

- Kyparissos

- Mavrovouni

- Porto Kagio

- Skoutari

- Oitylo

- Parasyros

- Stoupa

- Vatheia

Ancient

- Caenepolis (or Kainepolis)

- Gerenia

- Gytheion, Gythium (modern Gytheio)

- Kardamyli

- Las

- Leuctra

- Messa

- Oetylus (modern Oitylo)

- Taenarum

- Teuthrone

Prehistory

Mani and the entire Peloponnese Peninsula have been inhabited since prehistoric times. The Apidima Cave on the western side of the peninsula has yielded Neanderthal and Homo sapiens fossils from the Palaeolithic era.[7][8] As of 2019, a skull of Homo sapiens dating to more than 210,000 years ago discovered in Apidima is the oldest evidence of Homo sapiens in Europe. Neolithic remains have also been found along Mani's coast, in the Alepotrypa Cave among other sites.[9]

Ancient Mani

.jpg)

Mycenaean

The Mycenaean civilization (1900–1100 BCE) dominated Mani and the Peloponnese in the Bronze Age. Mani flourished under the Mycenaeans. A temple dedicated to Apollo was erected at Cape Matapan. It was later re-dedicated as the Temple of Poseidon. Homer refers to a number of towns in the Mani region. The "Catalogue of Ships" in the Iliad names Messa, Oetylus, Kardamyli, Gerenia, Teuthrone, and Las.[10]

The region featured in many myths and legends. One tradition told of a cave near Cape Matapan that led to Hades. Another legend said that Helen of Troy and Paris spent their first night together on the island of Cranae, off the coast of Gytheio.[11] It was once believed that in the 12th century BCE, the Dorians invaded Laconia, settling first in Sparta and by 800 BCE occupying Mani and all of Laconia. This proposed origin myth has since been disproven.

In the early Greek Dark Ages (c. 1050–800 BCE), Phoenicians arrived in Mani and are thought to have established a colony at Gytheion (modern Gytheio, called Gythium by the Romans). The colony collected the murex sea snail which was plentiful in the Laconian Gulf and processed into Tyrian purple, a valuable dye.[12]

The area around Mani came under the rule of the powerful city-state Sparta with the onset of the Archaic Period (800–480 BCE). Under Spartan rule, inhabitants of Mani were classified as belonging to the Perioeci social caste.[13]

Classical

Tainaron (Cape Matapan) became an important center for mercenary traffic in Classical times (c. 510–323 BCE),[14] Gytheio, only 27 km (17 mi) away from the city of Sparta, became Mani's—and Sparta's—major port. The coveted port was captured by Athenian forces in 455 BCE, during the First Peloponnesian War, a power struggle between Athens and Sparta and their respective allies fought in part to establish supremacy over the Peloponnese.[15]

The damaged city and docks were rebuilt; by the end of the war, Gytheio was the main shipyard for the new Spartan fleet.[16] Spartan hegemony in the Peloponnese lasted until 371 BCE, when the Thebans under Epaminondas defeated Sparta at Leuctra.[14]

Hellenistic

Throughout much of the Hellenistic period (323–30 BCE) the Mani Peninsula remained subject to Spartan hegemony. This era proved turbulent for Mani and Laconia, marked by frequent military engagements and shifting political allegiances for Mani.

Competition between rival powers resulted in a series of wars that eventually drew in the Kingdom of Macedon and the expanding Roman Republic: the Cleomenean War (229–222 BCE); the Social War (220–217 BCE); the Macedonian Wars (214–148 BCE); and the Laconian War (195 BCE). Gytheio, as a major port, remained an especially sought-after prize for all parties.

In 219–218 BCE, Philip V of Macedon invaded Mani as part of his campaign in Laconia. His forces besieged Gytheio and Las but failed to capture them.[17]

Nabis ascended to the Spartan throne in 207 BCE; he expanded Gytheio, transforming it into a vital port and naval arsenal.[18] Rome, allied with the Achaean League—Sparta's Greek rivals—captured Gytheio after a prolonged siege in 195 BCE; Sparta was the allies' next target. A peace treaty granted autonomy to Mani's coastal cities. These cities formed the Koinon or League, of Free Laconians, with Gytheio as its capital under the Achaean League's protection.[19]

Determined to retake the vital port of Gytheio, Nabis advanced on the city in 192 BCE.[20] A Roman fleet soon recaptured Gytheio. Nabis was murdered, and the polis Sparta was absorbed by the Achaean League.[21] The Spartans, still seeking access to a port, then seized Las, prompting the Achaeans to retaliate by seizing Sparta outright.[22]

Roman

The Romans emerged as the champion of the destructive and costly wars. With their victory at the Battle of Corinth in 146, all of Greece became a Roman possession.[23][24] The Peloponnese was administered as the province of Achaia. Rome did allow the Koinon of Free Laconians, which included Mani, to maintain its autonomy. In 375 a massive earthquake devastated Gythium.[25][26] Most of the ruins of ancient Gythium are now submerged in the Laconian Gulf.

In 395 CE, mainland Greece and the Peloponnese became part of the Byzantine Empire (formally the East Roman Empire), bringing over 500 years of centralized rule from Rome to an end. Mani would nominally be administered by the new government in Constantinople for over a millennium, with periodic interruptions due to unrest and foreign invasions. Mani's remoteness would limit Constantinople's influence.

Medieval Mani

Byzantine

The Mani Peninsula had a turbulent history during the long period of Byzantine Greece (395–1453), as various powers fought over it and the whole Peloponnese—known throughout much of this time as "Morea". Between 395 and 397, the Visigoths under Alaric I ravaged the Peloponnese and destroyed what was left of Gythium.[27] In 468, the Vandals under Gaiseric invaded Mani as a first step in their planned conquest of the Peloponnese, but were thwarted by a Maniot counter-attack at Caenepolis near Cape Matapan.[28] Some historians posit that in the 590s, groups of Pannonian Avars and Slavs attacked and occupied most of the western Peloponnese;[29] this claim is not universally accepted.[30]

Over the subsequent centuries, Mani was fought over by the Byzantines, the French, and the Saracens. In the wake of the Early Muslim conquests, Arabs captured the island of Crete in the 820s and established an emirate there. Arab raiders then began to attack Mani and the coastal cities of Peloponnese.[31][32] The Byzantines retook Crete in 961.

Christianization of Mani

Christianity was firmly established on mainland Greece, the Balkans, and Anatolia—the core territories of the Byzantine Empire—by as early as the 5th century. The Peloponnese, and Mani in particular, were quite late to adopt Christianity relative to these core regions, likely owing at least in part to the peninsula's isolation and foreboding terrain.

The monk Nikon "the Metanoite" (Greek: Νίκων ὁ Μετανοείτε) (c. 930 – 998) was commissioned by the Greek Orthodox Church to Christianize the areas of Mani and Tsakonia still practicing paganism. It was only after his efforts that most traces of the Ancient Greek religion and its traditions were eradicated from Mani. Nikon was canonized by the Greek Orthodox Church, and as St. Nikon became patron of Mani and Sparta.

Constantine VII in his De Administrando Imperio (c. 952) describes the Maniots thus:[33]

Be it known that the inhabitants of Castle Maina are not from the race of aforesaid Slavs (Melingoi and Ezeritai dwelling on the Taygetus) but from the older Rhomaioi, who up to the present time are termed "Hellenes" by the local inhabitants on account of their being in olden times idolaters and worshippers of idols like the ancient Greeks, and who were baptized and became Christians in the reign of the glorious Basil [Emperor Basil I (r. 867 – 886)]. The place in which they live is waterless and inaccessible, but has olives from which they gain some consolation.

Patrick Leigh Fermor wrote of the Maniots and the tradition of their conversion:

Sealed off from outside influences by their mountains, the semi-troglodytic Maniots themselves were the last of the Greeks to be converted. They only abandoned the old religion of Greece towards the end of the ninth century. It is surprising to remember that this peninsula of rock, so near the heart of the Levant from which Christianity springs, should have been baptised three whole centuries after the arrival of St. Augustine [of Canterbury] in far-away Kent.[34]

Crusader states

Following the Fourth Crusade and sack of Constantinople in 1204, the Mani Peninsula with Laconia and much of the Peloponnese became part of a "Frankish"[c] crusader state called the Principality of Achaea (1205–1432), primarily under French rule. In 1210, the Baron Jean de Neuilly began to rule Mani as Hereditary Marshal. He built the castle of Passavas on the ruins of Las, in part to subdue the recalcitrant Maniots. The castle controlled an important mountain pass between Gytheio and Oitylo.[35][36]

The Slavic Melingoi tribe then began raiding Laconia from the west, while in the east native Tsakonians agitated against French rule. In 1249, the new prince of Achaea, William II of Villehardouin, invested on the fortress of Monemvasia to keep the Tsakonians at bay. To contain the Melingoi, he built a castle at Mystras, in the Taygetus, overlooking Sparta. And—according to the 14th-century Chronicle of Morea—he built the castle of Grand Magne to stop Maniot raids. The castle was described as "at a fearful cliff with a headland above", and has been associated with the name "Mani" and variations since its construction. Despite its notoriety, the site has never been positively located; one possibility is Tigani.

By the mid-13th century, the resurgence of the Byzantine Empire under the Palaiologos dynasty had shifted the balance of power in Greece. In the 1250s the Pope appointed a "Latin," i.e., Roman Catholic, bishop to Mani, provoking resentment among the Orthodox Greeks, who soon removed him. In 1259 Byzantine forces captured the bishop at the Battle of Pelagonia.[37]

Byzantine Despotate of the Morea

Maniots had maintained a significant degree of autonomy during the Principality of Achaea's existence. From the mid-14th to mid-15th centuries, control over the region gradually shifted to a semi-autonomous province of the Byzantine Empire called the Despotate of the Morea (1349–1460).

Modern era

Ottoman rule

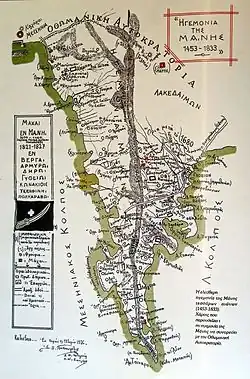

The Ottoman Empire succeeded in capturing Constantinople in 1453 and by 1460 assumed control of the Despotate of the Morea.[d] According to local tradition, members of noble Byzantine families such as the Palaiologoi fled to Mani following the fall of Constantinople.[38]

The Ottomans remained nominal rulers of Mani until the outbreak of the Greek revolution in 1821, with only a brief interlude of Venetian control. Mani was first administered by the Ottoman Eyalet of the Archipelago and then by the Morea Eyalet. Due to its remoteness and isolation, Mani in particular retained a degree of autonomy not present in other regions of Ottoman Greece. Mani retained its self-government in exchange for an annual tribute to the Sublime Porte, although this was only paid once.

Beginning in the late 17th century, Maniot chieftains, deemed beys, ruled Mani on behalf of the Ottomans. There were eight Beys of Mani in total; their rule concluded with the onset of the Greek War of Independence in 1821.

The first such bey was the Maniot Limberakis Gerakaris installed c. 1669. An oarsman in the Venetian fleet turned pirate, he was captured by the Ottomans and condemned to death. The grand vizier pardoned him on condition that he manage Mani as an Ottoman vassalage or client state.

Gerakaris accepted the offer and used his new position to pursue his standing feud with the powerful Maniot Stephanopouloi family. His forces besieged the family's seat at Oitylo, captured 35 of them, and had them all executed. During his twenty-year reign Gerakaris shifted allegiances between the Republic of Venice and the Ottomans.[15]

According to oral tradition, the last Bey of Mani, Petros Mavromichalis, proclaimed the revolution at Areopoli on 17 March 1821.[39] In 1826, a combined Ottoman and Egyptian army invaded Mani.

As Istanbul's power had been weakening, the local klephts—bandits who fought the Ottomans—made their strongholds in the rugged mountains of the Mani. The waning years of the empire also saw a sizeable Maniot emigration to Corsica.[40]

Greek independence

Many Maniots who stayed on the peninsula contributed to the struggle for independence. Following the Greek victory and establishment of the First Hellenic Republic, Maniots sought to retain the local autonomy they enjoyed under nominal Ottoman rule; many became dissatisfied with controls imposed by the central government in Athens.

Tensions came to a head in 1831 when Ioannis Kapodistrias, first Governor of the Hellenic State, ordered the arrest of Petros Mavromichalis for anti-government activities. The outraged sons of Mavromichalis responded to this affront to their honor by assassinating Kapodistrias in the town of Nafplio, in the eastern Peloponnese.[1]

In 1878, the national government imposed limits on local autonomy and strengthened its control of the Mani.[1]

Twentieth century

The violence of World War II and the Greek Civil War that followed engulfed the Peloponnese; Mani's population declined and continued to fall as emigration continued beyond the post-war decades. Many Maniots moved to major Greek cities or left the country for western Europe and the United States to join the Greek diaspora. Mani was considered a backwater until the 1970s, when the government started to build roads which made the peninsula more accessible by car. A tourist industry took hold, with ensuing population and economic growth.[1]

Recent history

The municipalities of East Mani and West Mani were established in 2011 by the Kallikratis Programme, a sweeping administrative reform that resulted in mergers of regional and local governments in the Peloponnese and across Greece.

Economy

Mani's economy is heavily oriented towards tourism and maritime activity.

Maniot culture

Maniots maintain a unique heritage among the regional subcultures of their fellow Greeks. By tradition, they claim descent from ancient Spartans, and to be heirs to their militaristic culture. [41][42]

Architecture

Mani is known for its unique tower houses, called pyrghóspita, and clan houses.[43] These towers were usually surrounded by other houses, family churches, and cemeteries, forming a fortified complex known as a xemóni in Greek, which served as a clan-based settlement.[44]

Cuisine

Maniot cuisine includes glina or syglino pork or pork sausage smoked with aromatic herbs such as thyme, oregano, and mint, and stored in lard with orange peel. Mani is also known for honey and extra-virgin olive oil, soft-pressed from partially-ripened Koroneiki olives grown on mountain terraces.

Dialect

Maniots have historically spoken a variety of Modern Greek defined as either a "dialect" or an "idiom".[45]

Regional linguistic peculiarities exist within Maniot Greek, particularly in surnames. Family names in Messenian Mani typically end in -éas, while those in Laconian Mani end in -ákos. There is also the -óggonas ending, a corruption of éggonos 'grandson'.[1]

Gallery

-

Pyrghóspita (tower houses) in Skoutari

Pyrghóspita (tower houses) in Skoutari -

Pyrghóspita in Vatheia

Pyrghóspita in Vatheia -

Port of Gytheio

Port of Gytheio -

Oitylo village

Oitylo village -

Diros Caves near Pyrgos Dirou

Diros Caves near Pyrgos Dirou -

Port of Areopoli

Port of Areopoli -

The Church of St. Spyridon in Kardamyli

The Church of St. Spyridon in Kardamyli -

Saints Theodoroi Church in Kampos

Saints Theodoroi Church in Kampos -

.svg.png) 1821 banner reading "Victory or Death"

1821 banner reading "Victory or Death"

Notes

- ^ Incorrectly labeled just "Epidaurus" on the map of Greece shown. Epidaurus Limera was an ancient town on the peninsula and the name is sometimes used to distinguish the peninsula from Cape Maleas at its tip. The town was a colony of the original Epidaurus on the Argolid Peninsula to the northeast

- ^ "Frankish" and "Franks" as used by the Greeks after 1204 are anachronisms. See Principality of Achaea and Frankokratia. From the latter: "The terms Frankokratia and Latinokratia derive from the name given by the Orthodox Greeks to the Western French and Italians who originated from territories that once belonged to the Frankish Empire, as this was the political entity that ruled much of the former Western Roman Empire after the collapse of Roman authority and power. The political situation proved highly volatile, as the "Frankish" states fragmented and changed hands and the Greek successor states re-conquered many areas." Francia, the historical Kingdom of the Franks, in fact existed from c. 480 to c. 800.

- ^ See note "b" on "Franks" and "Frankish" as used by the Greeks.

- ^ The Peloponnese would be called Morea throughout the early modern period.

References

- ^ a b c d e "Mani Peninsula Travel Guide". Greeking.me. 2023-11-23. Retrieved 2024-09-24.

- ^ Patrick Leigh Fermor, Mani: Travels in the Southern Peloponnese, p. 94

- ^ "At Least 6 Theories From Where Mani Got Its Name | Empiria Greece". empiriagreece.com. 2022-06-09. Retrieved 2024-09-24.

- ^ Beck, H.; Zimmermann, N.; McVicar, T. (2018). "Present and future Köppen-Geiger climate classification maps at 1-km resolution". Sci Data. 5.

- ^ Karakatsianis, Ioannis (2010-06-10). "A Clan-Based Society of South Greece and its Militarization After the Second World War: Some Characteristics of Violence and the Construction of Habitus in the South Peloponnese". History and Anthropology. 21 (2): 121–138. doi:10.1080/02757201003793713. ISSN 0275-7206.

- ^ Decision ΔΜΕΟ/Ε/779/1995, Classification of the National Road Network of Peloponnese

- ^ Delson, Eric (10 July 2019). "An early dispersal of modern humans from Africa to Greece – Analysis of two fossils from a Greek cave has shed light on early hominins in Eurasia. One fossil is the earliest known specimen of Homo sapiens found outside Africa; the other is a Neanderthal who lived 40,000 years later". Nature. 571 (7766): 487–488. doi:10.1038/d41586-019-02075-9. PMID 31337897.

- ^ Apidima Cave. Accessed on 10 July 2019.

- ^ Papathanasiou, Anastasia; Parkinson, William A.; Galaty, Michael L.; Pullen, Daniel J.; Karkanas, Panagiotis (2017-10-31). Neolithic Alepotrypa Cave in the Mani, Greece. Oxbow Books. ISBN 978-1-78570-648-6.

- ^ "Homer, The Iliad, Scroll 2, line 560". www.perseus.tufts.edu. Retrieved 2025-07-17.

- ^ Kassis 1979, p. 7.

- ^ Leigh Fermor 2006, p. 302.

- ^ Saitas 1990, p. 13.

- ^ a b Greenhalgh & Eliopoulos 1985, p. 20.

- ^ a b Leigh Fermor, Patrick (1958). Mani: Travels in the Southern Peloponnese. John Murray. p. 48.

- ^ Xenophon. Hellenica, 1.4.11 Archived 2012-09-30 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Greenhalgh & Eliopoulos 1985, p. 20.

- ^ Green 1990, p. 302.

- ^ Greenhalgh & Eliopoulos 1985, p. 20.

- ^ Smith 1873, Nabis Archived 2011-06-04 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Livy. Ab urbe condita libri

- ^ Cartledge & Spawforth 2002, p. 78.

- ^ P.J. Rhodes, p. 6.

- ^ F.W. Walbank, "Macedonia & Greece" in F. W. Walbank, A. E. Astin, M. W. Frederiksen, R. M. Ogilvie (ed.) Cambridge Ancient History 7.1: The Hellenistic World, 2008, p. 244.

- ^ Greenhalgh & Eliopoulos 1985, p. 21.

- ^ Greenhalgh & Eliopoulos 1985, p. 49.

- ^ Greenhalgh & Eliopoulos 1985, p. 21.

- ^ Leigh Fermor 1984, p. 120.

- ^ Greenhalgh & Eliopoulos 1985, p. 22.

- ^ Kazhdan 1991, pp. 1916–1919 under "SLAVS"

- ^ Kazhdan (1991), p. 1621

- ^ Bées & Savvides (1993), p. 236

- ^ Greenhalgh & Eliopoulos 1985, p. 22.

- ^ Leigh Fermor, Patrick (1958). Mani: Travels in the Southern Peloponnese. John Murray. p. 46.

- ^ Greenhalgh & Eliopoulos 1985, p. 23.

- ^ Kassis 1979, p. 23.

- ^ Greenhalgh & Eliopoulos 1985, p. 24.

- ^ Leigh Fermor, Patrick (1989) [1958]. Mani: Travels in the Southern Peloponnese. Penguin Books. pp. 27–29. ISBN 978-0-14-011511-6.

- ^ "On this day: March 17, 1821 – The people of Mani raised the banner of the Revolution". TheTOC (in Greek). 2023-03-17. Retrieved 2025-07-14.

- ^ "Not Quite Maniacs – Exploring Greece's Mani Peninsula". pictographical. 2015-06-30. Retrieved 2024-09-24.

- ^ The Bureau: Or Repository of Literature, Politics, and Intelligence. S.C. Carpenter. 1812. p. 36.

In this work, the author, giving an account of the conquest made in Greece by the Russians, and of the gallant defence made by the Maniotes (the descendants of the ancient Spartans) against the Turks, describes their invincible spirit with the eloquence of a Demosthenes or a Burke.

- ^ Harris, W. V.; Harris, William Vernon (2005). Rethinking the Mediterranean. Oxford University Press. p. 282. ISBN 978-0-19-926545-9.

Above all, the Maniots, who are said to be the true heirs of the Spartans and 'have always preserved their liberty' (Pococke, 1743, i. 178) serve as an illustration of this continuity. According to Lord Sandwich (1799, 31), '[these] descendants of the ancient Lacedemonians ... still preserve their love for liberty so great a degree, as never to have debased themselves under the yoke of the Turkish empire'.

- ^ Wagstaff, J. (December 1965). "House Types as an Index in Settlement Study: A Case Study from Greece". Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers. 69 – via ResearchGate.

- ^ Oikonomopoulou, Eleni; Delegou, Ekaterini T.; Sayas, John; Vythoulka, Anastasia; Moropoulou, Antonia (2023). "Preservation of Cultural Landscape as a Tool for the Sustainable Development of Rural Areas: The Case of Mani Peninsula in Greece". Land. 12 (8). Bibcode:2023Land...12.1579O. doi:10.3390/land12081579. ISSN 2073-445X.

- ^ For the distinction between "Greek dialects" and "Greek idioms", see Trudgill (2003) 49 [Modern Greek dialects. A preliminary Classification, in: Journal of Greek Linguistics 4 (2003), pp. 54–64] : "Dialekti are those varieties that are linguistically very different from Standard Greek ... Idiomata are all the other varieties."

Selected sources and further reading

- Adamakopoulos, T. (2014). "Discover Mani". Topo Guide. Retrieved 23 June 2025.

- Barrow, Bob (2000). Mani: A Guide to the Villages, Towers and Churches of the Mani Peninsula. Antonis Thomeas Services. ISBN 0-9537517-0-8.

- Bées, N. A. & Savvides, A. (1993). "Mora". In Bosworth, C. E.; van Donzel, E.; Heinrichs, W. P. & Pellat, Ch. (eds.). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition. Volume VII: Mif–Naz. Leiden: E. J. Brill. pp. 236–241. ISBN 978-90-04-09419-2.

- Birken, Andreas [in German] (1976). Die Provinzen des Osmanischen Reiches [The Provinces of the Ottoman Empire]. Beihefte zum Tübinger Atlas des Vorderen Orients, 13 (in German). Reichert. ISBN 3-920153-56-1.

- Carpenter, Stephen Cullen (1812). The Bureau: Or Repository of Literature, Politics, and Intelligence, Volume 1. S.C. Carpenter.

- Cartledge, Paul; Spawforth, Antony (2002). Hellenistic and Roman Sparta: A Tale of Two Cities. London. ISBN 0-415-26277-1.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Chapman, John. "Turkokratia: Kladas Revolt". Mani: A Guide and a History. Archived from the original on 2006-10-15. Retrieved 2007-01-19.

- Eisner, Robert (1993). Travelers to an Antique Land: The History and Literature of Travel to Greece. University of Michigan Press. ISBN 0-472-08220-5.

- Green, Peter (1990). Alexander to Actium: The Historical Evolution of the Hellenistic Age (Second ed.). Los Angeles: University of California Press. ISBN 0-500-01485-X.

- Greenhalgh, P. A. L.; Eliopoulos, Edward (1985). Deep into Mani: Journey to the Southern Tip of Greece. Faber and Faber. ISBN 0-571-13524-2.

- Harris, William Vernon (2005). Rethinking the Mediterranean. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-926545-9.

- Hellander, Paul (2008). Greece. Lonely Planet. ISBN 978-1-74104-656-4.

- Howarth, David Armine (1976). The Greek Adventure: Lord Byron and Other Eccentrics in the War of Independence. Atheneum. ISBN 0-689-10653-X.Homer. "Homer, The Iliad (Hom. Il. 2.581)". Perseus Digital Library. Samuel Butler, Ed. The Iliad of Homer. Rendered into English prose for the use of those who cannot read the original. Longmans, Green and Co. 39 Paternoster Row, London. New York and Bombay. 1898 (?). Retrieved 2025-07-19.

- Kassis, Kyriakos (1979). Mani's History. Athens: Presfot.

- Kazhdan, Alexander, ed. (1991). The Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-504652-8.

- Lefteris, Alexakis. "Form and evolution of Mani surnames". mani.org.gr (in Greek). Retrieved 19 July 2025.

- Leigh Fermor, Patrick (1984). Mani: Travels in the Southern Peloponnese. Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-011511-0.

- Leigh Fermor, Patrick (2006). Mani: Travels in the Southern Peloponnese. New York Review of Books. ISBN 9781590171882.

- Livy. "Titus Livius (Livy), The History of Rome, Book 1 (Liv. 1 pr)". Perseus Digital Library. Rev. Canon Roberts, Ed. Livy. History of Rome. New York, New York. E. P. Dutton and Co. 1912.

- "Máni". Encyclopedia Britannica. 17 August 2021. Retrieved 23 June 2025.

- Nicholas, Nick (2006). "Negotiating a Greco-Corsican Identity". Journal of Modern Greek Studies. 24: 91–133. doi:10.1353/mgs.2006.0009. S2CID 145285702.

- Papathanasiou, Anastasia; Parkinson, William A.; Galaty, Michael L.; Pullen, Daniel J.; Karkanas, Panagiotis (2017-10-31). Neolithic Alepotrypa Cave in the Mani, Greece. Oxbow Books. ISBN 978-1-78570-648-6.

- Paroulakis, Peter H. (1984). The Greeks: Their Struggle for Independence. Hellenic International Press. ISBN 978-0-9590894-0-0.

- Roessel, David (2001). In Byron's Shadow: Modern Greece in the English and American Imagination. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780198032908.

- Roumeliōtēs, Giannēs Ch. (2002). Herōides tēs Lakonias kai tēs Manēs holēs (1453–1944). Ekdoseis Adoulōtē Manē. ISBN 960-87030-1-8.

- Saitas, Yiannis (1990). Greek Traditional Architecture: Mani. Athens: Melissa Publishing House.

- Stamatoyannopoulos, George; Bose, Aritra; Teodosiadis, Athanasios; Tsetsos, Fotis; Plantinga, Anna; Psatha, Nikoletta; Zogas, Nikos; Yannaki, Evangelia; Zalloua, Pierre; Kidd, Kenneth K.; Browning, Brian L. (8 March 2017). "Genetics of the Peloponnesean populations and the theory of extinction of the medieval Peloponnesean Greeks". European Journal of Human Genetics. 25 (5): 637–645. doi:10.1038/ejhg.2017.18. ISSN 1476-5438. PMC 5437898. PMID 28272534.

- Smith, William (1873). Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology. London: John Murray.

- Trudgill, Peter (2003). "Modern Greek Dialects: A Preliminary Classification". Journal of Greek Linguistics. 4: 45–63. doi:10.1075/jgl.4.04tru. S2CID 145744857.

- "Vendetta". mani.org.gr. Retrieved 19 July 2025.

- Xenophon. "Xenophon, Hellenica". Perseus Digital Library. Carleton L. Brownson, Ed. Xenophon in Seven Volumes, 1 and 2. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA; William Heinemann, Ltd., London. vol. 1:1918; vol. 2: 1921.

- Yerasimos, Marianna (2020-05-27). "Evliya Çelebi Seyahatnâmesi'nde Yunanistan: Rota ve Güzergâhlar". In Anadol, Çağatay; Eldem, Edhem; Pekin, Ersu; Tibet, Aksel (eds.). Bir allame-i cihan : Stefanos Yerasimos (1942–2005). IFEA/Kitap yayınevi (in Turkish). İstanbul: Institut français d’études anatoliennes. pp. 735–835. ISBN 978-2-36245-044-0. Retrieved 2023-02-06.

- "1906: I ematiri venteta anamesa se Maniates ke Kritikous" 1906: Η αιματηρή βεντέτα ανάμεσα σε Μανιάτες και Κρητικούς [1906: The bloody feud between Maniots and Cretans]. cretapost.gr (in Greek). 2018-09-14. Archived from the original on 2018-07-02. Retrieved 2025-07-19.

External links

- . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). 1911.

- A guide and history of Mani by John Chapman

- Paintings and drawings of Mani by the German painter and inhabitant of Gerolimenas, Karl-Heinz Herrfurth