Madge Clifford

Margaret Mary Clifford (later Comer; 1896–20 April 1982),[1][2] from Tralee, County Kerry, was an Irish republican and officer in Cumann na mBan, of which organisation she became quartermaster in its central branch in Dublin. She joined Cumann na mBan at its inception in 1914 and was actively involved in the nationalist struggle from then onwards, including working for Dáil Éireann. She took the anti-treaty side in the Irish Civil War and played a prominent role under its senior leadership. "Emotionally she was deeply involved in Irish Republicanism" and "personally acquainted with all the members of the army council as well as with most of the members of the Provisional Government".[3]

Early life

Clifford was born in Ballybane, Firies, County Kerry,[4] one of nine children to Jeremiah Clifford, a farmer and Fenian,[5] and Mary Brosnahan. Both her parents, from Firies parish, were involved in Land League and her mother had participated in the Castlefarm incident and its aftermath. Clifford attended Knockaderry National School, Farranfore, then went to Presentation Girls Secondary School in Tralee. She qualified as a typist, having attended a secretarial school in Tralee.

Revolutionary activities

Irish War of Independence

Clifford is described as being "at the centre of action throughout the revolution".[6] She was one of the few women to gather, along with Irish Volunteers from all over Kerry, at the Rink Volunteer Hall in Tralee on Easter Saturday 1916 to await the planned arrival of weapons, procured from Germany by Roger Casement, on the ship Aud.[7] She came to Dublin in 1917 and joined the central branch (Parnell Square) of Cumann na mBan, holding the officer rank of quartermaster.[8] She was at the headquarters of Sinn Féin in Harcourt Street when the results of the 1918 election came in.

She was known to Austin Stack from her Tralee days and he asked her to be his "confidential" private secretary in the Ministry of Home Affairs in autumn 1919.[9][10] Now attached to Dáil Éireann, her work included the setting-up of the Republican Courts. She was required not to parade in public as a member of Cumann na mBan duties but instead became what she called a "freelance" helper who supervised arms dumps, gathered intelligence and moved weapons.[8] Clifford assisted Michael Collins and Harry Boland at GHQ and brought letters to and from there to captives in Mountjoy Prison.[8] She also pretended to be trying to find accommodation in more secluded districts of the city in order to keep watch on houses and the people living there.[11] Clifford later pointed out some of the British agents to be killed by the IRA on Bloody Sunday. At one stage she was entrusted with safe storage of gold collected by the republican movement until it could be passed to Collins.[8]

During the truce period, Clifford was sent down to her native Kerry for several weeks.[8]

Irish Civil War

After the Ministry of Home Affairs was shut down in February 1922 she continued to work from the Sinn Féin offices in Suffolk Street. Clifford opposed the Anglo Irish Treaty.[8] She was one of five women in the Four Courts on 28 June 1922 and was working on a proclamation with Liam Mellows when the first shells from Free State forces landed near them.[12] She brought in doctors and nurses and acted as a medical orderly until the surrender of the IRA garrison.[8] Clifford was hands on, baking bread for a garrison of 180 in the Four Courts' ovens and going round with it and a bucket of tea even in the early hours of the final morning as the bombardment intensified.[13]

Clifford was rescued from amongst the prisoners being brought out of the Four Courts by a Republican soldier dressed in a Free State uniform who had instructions to obtain the garrison's documents and files; she had left the Four Courts with very important papers belonging to Joe McKelvey, which she gave to republican leaders Cathal Brugha and Oscar Traynor when she reported for Cumann na mBan duties now that the civil war had started.[14][8] She then went to the Hammond Hotel and was sent in a failed mission to infiltrate the Provisional Government buildings.[15]

Clifford received orders from IRA assistant chief of staff Ernie O'Malley to join his column in south Leinster; on the way out of Dublin the car she was travelling in came under fire from Free State troops in Templeogue.[16] In Wicklow, Kildare, Carlow and Wexford she was in action with O'Malley's troops.[17]

She soon became full-time secretary and "functioned as a really efficient adjutant" to O'Malley.[8] He recalls that she was quite well known in the republican movement and changed her appearance frequently.[18] She considered him an IRA leader that was "very very strict on men in demanding work. He was friendly but demanding. He wanted the work done".[19]

Following the latter's arrest on 4 November 1922 she was asked by Éamon de Valera to serve as secretary to IRA chief of staff Liam Lynch at GHQ in the Tower House, Santry, north Dublin. From then until the end of March 1923 she was a constant presence in this large building that was home to the Fitzgerald family, prosperous Dublin merchants who were sympathetic to the republican cause. When Lynch and his small staff arrived, secret rooms and hiding places were constructed and the building became a fully functioning military command centre, with secrecy of the greatest importance.[20] Clifford's duties included corresponding with O'Malley in prison and keeping him informed of key developments.[21] She recollected that the surrender proposed by his deputy Liam Deasy from prison had affected Lynch very badly and left him broken-hearted.[22] Lynch also trusted Clifford enough to declare to her in early 1923 that he was angered sufficiently by Tom Barry's proposals for peace to feel like having the man shot.[23] After the death of Lynch in April 1923 Clifford was essentially secretary to the Republican government until the end of the civil war less than two months later.[24]

Fellow republican Todd Andrews admired Clifford whom he felt was as "well informed about every detail of the IRA as O'Malley himself".[25]

In her period as O'Malley's and Lynch's secretary, Clifford defied the norm by wearing her hair in a bob.[26][18]

Post-civil war

After the civil war she worked in Sinn Féin HQ in Suffolk Street, Dublin, until 1925.

On 31 December 1935, Clifford applied for a Free State pension awardable to combatants in the struggle against the British. After much delay this was awarded in late 1940 but not at the officer rank she claimed. While her appeal was unsuccessful, in May 1941 she received payment of c. £25 per annum for the lowest officer grade backdated to October 1934.[27] Amongst her referees was O'Malley, with whom she remained close and who nicknamed her "Mutt".[8][28]

Her period as an official of the Dáil was recognised by act of that parliament in 1936. As one of eight women whose marriage precluded possible reinstatement as a civil servant, she received a compensatory payment of £300.[29]

After the Second World War, Clifford was approached by Seán MacBride to stand for Clann na Poblachta in the 1947 election but declined for family reasons. Later she changed her mind and joined that movement.[5]

Clifford assisted republican Florrie O'Donoghue with dates for his biography of Lynch published in 1954. She also provided information to author Desmond Greaves for his 1971 biography of Mellows.[30]

She held traditional republican views against partition and remained in contact with old comrades. She supported later republican campaigns in Northern Ireland. It is clear that as late as July 1969 she had very little time for MacBride or de Valera, whom she termed "half-breeds", or the Fianna Fáil party machine. She felt herself "very bitter": "Today it is all money, money, money. The people are changed. They have lost all their lovely pride".[5]

Personal life

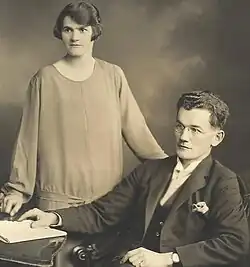

While canvassing with Maud Gonne and Constance Markievicz in Rathdowney, County Laois, for a by-election in 1925 she met local doctor John Joseph "Jack" Comer, originally from Williamstown, County Galway. Formerly medical officer to the IRA's 3rd Southern Division, he was one of the last civil war prisoners to be released in 1924.[31] They were married later in 1925 and had eight children: daughters Una, Maureen, Biddy, Eileen (Dodie), Norrie and Fin and sons Simon and Jerry. Of these, six became doctors, one a solicitor and one a nurse.[32][33] The family lived in Fairy Hill, Rathdowney. Jack Comer went into private medical practice due to being prevented from working for the state on account of his republican views.[34]

She returned to Kerry after her husband retired and is buried in the Clifford family tomb in Aglish, Firies, County Kerry.

Clifford's grandson is Kerry author and historian Dr Tim Horgan.[35][36]

Through her daughter Dr Norrie Buckley, Madge Clifford is the great-grandmother of actress Jessie Buckley.[37]

References

- ^ 'Superannuation Act, 1936'. Irish Statute Book, undated. Retrieved 27 June 2025

- ^ 'Women in 20th-Century Ireland, 1922-1966: Sources from the Department of the Taoiseach'. National Archives, undated. Retrieved 27 June 2025

- ^ C.S. Andrews (1979). Dublin Made Me (Dublin, Mercier Press), p. 245

- ^ 'Statement of Patrick Riordain, Longfield, Firies, County Kerry' (p. 4). Military Archives, 29 July 1954. Retrieved 1 July 2025

- ^ a b c 'Desmond Greaves Journal, Vol. 20, 1968-69, 1 July 1968 – 31 August 1969'. Desmond Greaves Archive, undated. Retrieved 14 August 2025

- ^ Gavin Foster (2023). "Patterns of Irish Civil War Memory in Later-Generation Oral Histories", in Contemporary European History, vol. 32, special issue 4, "New Histories of the Irish Revolution", 604-617

- ^ Raynor Winn, 'The Blacksmith Volunteer Remembered'. The Advertiser, 30 March 2023. Retrieved 26 June 2025

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j '"Comer, Madge"' (pp. 10–11, 21–24, 30, 32-33, 35-38, 40–42, 55, 57). Military Archives, various dates. Retrieved 27 June 2025

- ^ O'Malley, C.H. and Horgan, T. (ed.) (2012). The Men Will Talk to Me. Kerry Interviews by Ernie O'Malley (Cork: Mercier Press), pp. 43 and 181

- ^ Daithi O’Donoghue (1951), 'Financing the First and Second Dail Eireann'. General Michael Collins, undated. Retrieved 14 August 2025

- ^ Liz Gillis, "Bloody Sunday, 1920: 'By their destruction the air is made sweeter'". The Irish Times, 3 June 2020. Retrieved 14 July 2025

- ^ Ernie O'Malley, "Madge Clifford Interview", Ernie O'Malley Papers, University College Dublin. UCDA P17b/103, 1A

- ^ Marie Comerford (2021). On Dangerous Ground: A Memoir of the Irish Revolution (Dublin, Lilliput Press), pp. 258, 265

- ^ O'Malley, "Madge Clifford Interview", 1A, 1B

- ^ O'Malley, "Madge Clifford Interview", 2A

- ^ O'Malley, "Madge Clifford Interview", 2A

- ^ O'Malley, "Madge Clifford Interview", 2A-4A

- ^ a b Ernie O'Malley (1978). The Singing Flame (Dublin, Anvil Books), p. 160

- ^ Richard English (1998). Ernie O'Malley: IRA Intellectual (Oxford, Clarendon Press), p. 110

- ^ O'Malley, "Madge Clifford Interview", 34A–40A

- ^ O'Malley, The Singing Flame, p. 302

- ^ Michael Hopkinson (1998). Green against Green: The Irish Civil War (Dublin, Gill and Macmillan), p. 231

- ^ Gerard Shannon (2023). Liam Lynch: To Declare a Republic (Newbridge, Merrion Press), p. 239

- ^ O'Malley, "Madge Clifford Interview", UCDA P17b/89, 41A

- ^ John Dorney, 'Women, the Vote and Nationalist Revolution in Ireland'. The Irish Story, 9 February 2018. Retrieved 27 June 2025

- ^ Eve Morrison (2020). 'Fighting Time: Temporality, Time Reform and the Irish Revolutionary Present' (p. 19). University of Oxford. Retrieved 14 August 2025

- ^ "E5143 'Clifford, Madge'" (pp. 21-23, 32-33). Military Archives, various dates. Retrieved 21 July 2025

- ^ 'Papers of Frances-Mary Blake'. UCD Archives, P244/93 (Copies of Ernie O’Malley's correspondence, 1923). UCD 2018. Retrieved 14 August 2025

- ^ 'Bille Aois-Liúntas, 1936. Superannuation Bill, 1936. (p. 18)' Houses of the Oireachtas, 31 March 1936. Retrieved 14 August 2025

- ^ 'Desmond Greaves Journal, Vol. 22, 1970-71, 1 June 1970 – 31 July 1971'. Desmond Greaves Archive, undated. Retrieved 14 August 2025

- ^ O'Malley and Horgan, Kerry Interviews, p. 37

- ^ 'Comer Simon: Death'. The Irish Times, 26 February 2011. Retrieved 27 June 2025

- ^ John O'Mahony, 'Archbishop pays moving tribute to Dr Norrie'. Killarney Today, 24 July 2018. Retrieved 12 August 2025

- ^ Uinesann Mac Eoin (1987). "'Survivors'. The Story of Ireland's Struggle as told through some of her Outstanding Living People recalling Events from the Days of Davitt, through James Connolly, Brugha, Collins, Liam Mellows, and Rory O'Connor, to the Present Time" (Argenta, Dublin), p. 52. Military Archives, 27 April 2020. Retrieved 15 August 2025

- ^ Barry Roche, 'Catholic Church should apologise for treatment of Irish republicans during Civil War, event hears'. The Irish Times, 11 September 2022. Retrieved 27 June 2025

- ^ 'Voices of the fighters from Independence and Civil War brought back to life'. Irish Independent, 2 July 2012. Retrieved 27 June 2025

- ^ John O'Mahony, 'Killarney saddened by passing of Dr Norrie Buckley'. Killarney Today, 21 July 2018. Retrieved 12 August 2025