Madame X (1966 film)

| Madame X | |

|---|---|

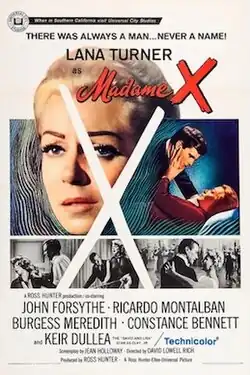

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | David Lowell Rich |

| Screenplay by | Jean Holloway |

| Based on | Madame X by Alexandre Bisson |

| Produced by | Ross Hunter |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Russell Metty |

| Edited by | Milton Carruth |

| Music by | Frank Skinner |

Production companies |

|

| Distributed by | Universal Pictures |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 100 minutes[1] |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

Madame X is a 1966 American suspense drama film[2] directed by David Lowell Rich and starring Lana Turner, John Forsythe, Ricardo Montalbán, Burgess Meredith, Constance Bennett, and Keir Dullea. Based on the 1908 play of the same name by French playwright Alexandre Bisson, it follows Holly Anderson, the wife of a wealthy American diplomat who, under the pressure of her mother-in-law, fakes her death after the demise of her lover. Holly spends the following fifteen years abroad under a false identity before becoming embroiled in a legal battle after she commits a murder, during which she is unknowingly represented by the son—now a successful attorney—whom she was forced to abandon.

The film rights to the project were purchased from Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer by Turner herself, who entered a co-production agreement with producer Ross Hunter. The screenplay was adapted from Bisson's play by Jean Holloway. Filming of Madame X took place on the Universal Studios Lots in the spring of 1965, with eighty-four film sets being constructed for the production.

Released by Universal Pictures in the spring of 1966, Madame X received mixed reviews from film critics, though many remarked Turner's lead performance as a key strength. In Italy, Turner's performance won her the David di Donatello for Best Foreign Actress at the 1966 David di Donatello Awards as well as the award for Best Foreign Actress at the Taormina Film Festival.

Plot

Holly Parker, a lower-class shopgirl from San Francisco, marries into the wealthy Anderson family of Fairfield, Connecticut. Her husband Clayton is a diplomat with strong political aspirations. Her mother-in-law Estelle looks down on her and keeps a watchful eye on her activities. Lonely and reclusive during Clayton's long, frequent assignments abroad, Holly forms a relationship with a well-known playboy, Phil Benton. Clayton suddenly returns and informs Holly that he has secured a promotion in Washington, D.C., where he wishes to take Holly and their son Clay to begin a regular family life. Holly agrees and goes to Phil's apartment to end their relationship. Phil reacts by trying to physically force Holly to stay, but tumbles down a staircase in the struggle and dies. Holly panics and leaves the scene. She is confronted by Estelle, who had hired a detective to follow her and knows about Phil's accident. Estelle blackmails Holly into faking her death and disappearing to Europe under a false identity rather than facing murder charges and ruining her husband's political career with the scandal. Estelle arranges for Holly to be secreted away at night from the family yacht, never to see her husband or son again.

Holly, devastated by the loss of her son, falls ill with pneumonia on the side of a street in Denmark on Christmas Eve. She is rescued by a charming pianist named Christian who helps her receive medical treatment and recuperate under a nurse's care. Holly and Christian grow close as she accompanies him on tour, but when he proposes marriage, she declines and then runs away from Christian. Holly slowly sinks into depravity and alcoholism, including a one-night stand with a man who steals her money and jewelry.

With Estelle's blackmail payments cut off, Holly goes to Mexico where she lives in a sleazy apartment and cannot afford her rent. She befriends an American neighbor named Dan Sullivan, who plies her with alcohol. On Christmas Eve, a drunken Holly reveals her past to Dan. He persuades Holly to join him in New York to work for him, but while there, she realizes that he is actually trying to blackmail Clayton, who is now governor of the state and a leading candidate for his party's presidential nomination. Holly shoots and kills Dan when he threatens to expose her deception to her son. The police arrest her and, refusing to reveal her identity, she signs a confession with the letter "X" and refuses to speak. The court-appointed defense attorney happens to be her son, Clay Jr., though she does not recognize him.

Holly refuses to reveal her name throughout the trial, saying nothing in her defense. Clay, in his first trial as a lawyer, devises a defense strategy to paint Sullivan as a career criminal who caused his own death. At the end of the trial the prosecutor is giving his summation to the jury and says that Clay is the son of the governor and states his full name. Holly spots Clayton Sr. in the gallery and suddenly realizes that her attorney is in fact her long-lost son. Holly takes the stand, admitting that she killed Sullivan to protect her son, who believes her to be dead, so he will not know the type of woman she has become.

While the jury is deliberating, Clay, who has grown close to Holly despite not knowing that she is his mother, visits her in her holding cell and implores her to reach out to her son. She does not reveal her identity to him but tells him he has been like a son to her. Then, having spent her final moments with her son and overcome with emotion, she dies suddenly. Clay tells his father that he had come to love "X".

Cast

- Lana Turner as Holly Parker Anderson

- John Forsythe as Clay Anderson

- Ricardo Montalbán as Phil Benton

- Burgess Meredith as Dan Sullivan

- Constance Bennett as Estelle Anderson

- Keir Dullea as Clay Anderson Jr.

- Teddy Quinn as young Clay Anderson Jr.

- John van Dreelen as Christian Torben

- Virginia Grey as Mimsy

- Warren Stevens as Michael Spalding

- Carl Benton Reid as The Judge

- Frank Maxwell as Dr. Evans

- Kaaren Verne as Nurse Riborg

- Joe De Santis as Carter

- Frank Marth as Detective Combs

- Bing Russell as Police Sergeant Riley

- Teno Pollick as Manuel Lopez

- Jeff Burton as Bromley

- Jill Jackson as Police Matron

Production

Development

Producer Ross Hunter, who had enjoyed great success remaking projects, had long been interested in bringing the Bisson play to the screen, but Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM), which had produced film adaptations in 1929 and 1937, owned the rights.[3] After reading the play again at a bookstore, Hunter became enthusiastic again. "I knew that if I kept the trial scene and brought the rest up to date I'd have something," he said.[4] Turner herself bought the rights to the film from MGM, and entered a co-production deal with Hunter.[3]

Hunter announced the film in May 1962 as part of a slate of six projects, also including The Thrill of It All, The Chalk Garden, If a Man Answers, a new Tammy film and a remake of The Dark Angel. The script was written by Jean Holloway, who had written for Hunter in radio, despite the fact that the play had been enacted many times before. "You really have to tell a whole new story," said Holloway.[5]

In October 1962, Hunter said that he hoped that Douglas Sirk would direct,[6] but Sirk declined due to his ailing health.[3] Instead, television director David Lowell Rich was hired to direct the film.[3]

Casting

Lana Turner, who had previously made Imitation of Life and Portrait in Black for Hunter, was enlisted as the film's star from the beginning.[7] "Tearjerkers are more difficult to make than any other type of movie," said Hunter. "Critics would seem to categorize them and look down on them; it is word of mouth that is their best press agent. It's all very sad in a way; maybe this is why we're not building great woman stars for audiences today. Audiences need to let their emotions out."[4]

Hunter signed a seven-year contract with Universal in November 1964, with Madame X among the leading projects. In February 1965, Keir Dullea's casting was announced.[8] Gig Young was offered the older male lead but asked for too much money, so Hunter hired John Forsythe.[9] The role of Estelle Anderson, Holly's mother-in-law, was originally offered to Madeleine Carroll, though Constance Bennett was ultimately cast in the part.[10]

Hunter said he knew that he needed "the one scene the public would remember", the trial scene. He modernized the play and introduced new characters.[4] "Now we have a mother and child relationship that should be seen by parents and children alike," said Hunter. "And I believe that for the first time since The Bad and the Beautiful, Lana is giving a really great performance."[4]

Filming

Filming started on March 2, 1965.[11] The film was a co-production between Universal and Turner's company, Eltee.[12] Turner owned fifty percent of the film and its profits.[10] Principal photography took place on the Universal Studios backlots.[10] A total of eighty-four sets were constructed for the film, the most used for any Ross Hunter production at that time.[10] $1.5 million worth of jewelry was loaned from a New York City firm to be worn by the film's female leads, Turner and Bennett.[10] Turner's agreed filming schedule was between the hours of 9:00 a.m. and 6:00 p.m., with no interruptions during her lunch break.[10] In May 1965, Hedda Hopper reported that Turner was treating Hunter "like a dog" and was "nothing but trouble" on the set,[13] though both Hunter and Turner denied such claims in subsequent interviews.[3]

Turner feuded with her longtime makeup artist Del Armstrong during the production, as she felt self-conscious about her unflattering appearance as her character progressed between ages 30 and 55 in the film.[3] "When I thought he'd made me look horrible enough, he said 'You ain't seen nothing yet,' and he meant it," said Turner. "I mean, I've had some bad mornings in my time, but I've never looked like that."[3]

Soundtrack

The film contains an original song by Austrian composer and conductor Willy Mattes (also known as Charles Wildman) titled "Love Theme from Madame X" (alternatively named "Swedish Rhapsody"). It was recorded by George Greeley for his 1968 album The World's Ten Greatest Popular Piano Concertos[14] with other cover versions by Jackie Gleason and Andre Kostelanetz.

Release

Madame X had its world premiere in Miami, Florida on March 3, 1966, followed by a Los Angeles premiere on March 16, 1966.[10] During its theatrical run in Miami, the film earned $47,753 in its first five days of release at four theaters.[10]

Home media

Universal Pictures Home Entertainment released the film on DVD as a double feature with Portrait in Black (1960) on February 5, 2008.[15] Kino Lorber issued a Blu-ray edition in 2019.[16]

Reception

Critical response

Madame X received mixed reviews from critics at the time of its original release.[10] Philip K. Scheuer of the Los Angeles Times praised the film's performances, particularly that of Turner.[17] The New York Times also praised the film, writing: "The sheer weight of such a teary theme is bound to be affecting to some extent, even played on a banjo. Not here, it isn't. As a fitting showcase for Miss Turner, the producer, Ross Hunter, has supplied an expensive, rainbow-hued decor, a viable supporting cast, and a director, David Lowell Rich, who reverentially wafts the story along from aches to pains and worse."[18]

Jeanne Miller of the San Francisco Examiner found the film overly melodramatic, but conceded that Turner "survives this avalanche of disaster with remarkable aplomb. And she even succeeds in transcending the bromidic plotline here and there."[19] Kaspar Monahan of The Pittsburgh Press also praised Turner's performance, noting that she "manages to keep her weepy, impossible role in focus, to invest it with dignity and, under the circumstances, considerable believability."[20] Variety also praised Turner's acting, noting that she "takes on the difficult assignment of the frustrated mother, turning in what many will regard as her most rewarding portrayal."[21] Pauline Kael, however, wrote unfavorably of Turner's performance, declaring: "She's not Madame X; she's brand X; she's not an actress."[22]

Ken Barnard of the Detroit Free Press felt the film had a "dated melodramatic air," but praised Turner's acting in "an overripe role."[23]

Accolades

| Institution | Year | Category | Recipient | Result | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| American Film Institute | 2008 | Top 10 Courtroom Dramas | Madame X | Nominated | [24] |

| David di Donatello | 1966 | Best Foreign Actress | Lana Turner | Won | [25] |

| Taormina Film Festival | 1966 | Best Foreign Actress | Lana Turner | Won | [10] |

Legacy

In 2021, the British Film Institute ranked Madame X among actress Lana Turner's ten most "essential" films, noting: "Turner’s performance is one of her most impressive, taking her character from the prim, naive woman of the opening scenes to the desperate wreck of the finale, with gut-wrenching conviction."[26]

Novelization

Writer Michael Avallone wrote a novelization of the film,[10] published in 1966 by Popular Library.

See also

References

- ^ "Madame X (1966)". British Board of Film Classification. Archived from the original on July 9, 2025.

- ^ "Madame X". TV Guide. Archived from the original on July 2, 2025.

- ^ a b c d e f g Landazuri, Margarita. "Madame X (1966)". Turner Classic Movies. Archived from the original on December 27, 2017.

- ^ a b c d Scheuer, Philip K. (April 18, 1965). "Tear-jerker Famine; It's a Crying Shame". Los Angeles Times. p. M3 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Rewrites Tough for Jean Holloway". Los Angeles Times. February 1, 1966. p. C6.

- ^ Archer, Eugene (October 6, 1962). "3D MOVIE VERSION OF 'MADAME X' SET: Ross Hunter to Film Drama in Color With Lana Turner". The New York Times. p. 12.

- ^ Thompson, Howard (May 16, 1962). "FILMMAKER TALKS ABOUT 5 PROJECTS: Hunter, Here in Visit, Tells of MacDonald-Eddy Plan; 'Tammy Takes Over' Is Next; Joanne Woodward to Star; British Film Opens Today; 7 Vie for Golden Laurel; Albert Lamorisse Visits". The New York Times. p. 33.

- ^ Hopper, Hedda (February 12, 1965). "Looking at Hollywood: 'Greatest Story' Called Magnificent Spectacle". Chicago Tribune. p. C12.

- ^ Hopper, Hedda (February 17, 1965). "Alfred Hitchcock to Address Editors". Los Angeles Times. p. D9 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k "Madame X". AFI Catalog of Feature Films. American Film Institute. Archived from the original on July 2, 2025.

- ^ Hopper, Hedda (March 4, 1965). "O'Toole Bypassing 'Lord Jim' Premiere: Star Remains Here One Day Before Taking Off for Tokyo". Los Angeles Times. p. C8 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Those Old Flicks Make Lana Rich". Chicago Tribune. April 17, 1966. p. M13 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Hopper, Hedda (April 14, 1965). "Looking at Hollywood: Sophia World's Favorite, Says Zanuck". Chicago Tribune. p. A1 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "George Greeley With The Warner Bros. Studio Orchestra Conducted By Ted Dale - The World's Ten Greatest Popular Piano Concertos". Discogs. Retrieved May 14, 2020.

- ^ "Portrait in Black / Madame X". Universal Pictures Home Entertainment. Archived from the original on July 2, 2025.

- ^ Barrett, Michael (June 11, 2019). "Hunter, Turner, Soaper, Weeper: 'Portrait in Black' and 'Madame X'". PopMatters. Archived from the original on July 2, 2025.

- ^ Scheuer, Philip K. (March 16, 1966). "'Madame X' Remake of Old Story". Los Angeles Times. p. 17 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "'Madame X,' Durable Weeper, Here Again With Lana Turner". The New York Times. April 28, 1966. Archived from the original on May 27, 2020.

- ^ Miller, Jeanne (March 17, 1966). "Lana's Version of 'Madame X'". San Francisco Examiner. p. 31 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Monahan, Kaspar (March 31, 1966). "Lana Turner At Her Peak In 'Madame X'". The Pittsburgh Press. p. 32 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Variety Staff (December 31, 1966). "Madame X". Variety. Archived from the original on July 9, 2025.

- ^ Schechter 2008, p. 684.

- ^ Barnard, Ken (March 9, 1966). "Lana's New One, 'Madame X' And Its Oldtime Melodrama". Detroit Free Press. p. 6D – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "AFI's 10 Top 10 Nominees" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on July 16, 2011. Retrieved August 19, 2016.

- ^ Valentino 1976, p. 251.

- ^ Walker, Chloe (February 8, 2021). "Lana Turner: 10 essential films". British Film Institute. Archived from the original on February 9, 2025.

Sources

- Schechter, Harold (2008). True Crime: An American Anthology: A Library of America Special Publication. New York City, New York: Library of America. ISBN 978-1-598-53031-5.

- Valentino, Lou (1976). The Films of Lana Turner. Seacaucus, New Jersey: Citadel Press. ISBN 978-0-8065-0553-4.

External links

- Madame X at the AFI Catalog of Feature Films

- Madame X at IMDb

- Madame X at the TCM Movie Database