Ludovic McLellan Mann

Ludovic McLellan Mann (1869 in Langside, Glasgow–1955) was a wealthy Scottish archaeologist and antiquarian.[1] By profession, Mann was a chartered accountant, actuary and insurance broker who was chairman of the firm Mann, Ballantyne & Co, Insurance Brokers and Independent Neutral Advisors that had offices in Glasgow and London. Mann invented consequential fire loss indemnity,[a] However, Mann was well known as an self-taught amateur archaeologist who had a fascination with the prehistory of south-west Scotland with a particular focus on Argyll and Glasgow areas. His enthusiasm for prehistory was equally matched with his compulsion to promote and publicise his work as much as possible by publishing fieldnotes of his expeditions in both the national and international press. It also included him directing tours of his own excavations and site discoveries.[3] This led to Mann being labelled as Glasgow's original media influencer.[3] However being self-taught, meant his theories were often in disagreement with mainstream archeological academia.[4]

Life

Ludovic Mann was born in Langside, Glasgow.[5] His father was the Glasgow accountant John Mann (1827–1910), who lost a fortune[5] after the spectacular collapse in October 1878 of the City of Glasgow Bank[5] but narrowly avoided bankruptcy.[6] His mother was the novelist Mary Newton Harrington (1834–1917) who wrote the novels, "Sandy and other Folk" and "Marion Emery and her friends : a tale of southern Scotland" and "The Wooin' o' Mysie".[7] The couple had a family of four sons and two daughters.[8] The eldest son was John Mann (1863–1955), a prominent accountant and businessman who became Director of Contracts in the Ministry of Munitions. Mann used cost accounting to save large amounts of money during munitions production leading up to World War I.[9] The second son was Harrington Mann (1864–1937), a noted portrait painter who was member of the Glasgow Boys movement in the 1880's.[9] The third son was Arthur Mann (1866-?) who emigrated to Argentina to build a fortune and became the owner of a Estancia. Ludovic was the youngest son.[5] His oldest sister was Katherine Mann, a poet[7] and youngest sister was Hilda Harrington Mann (1873–1964).

Education

In 1882, when Mann left school, he began training as a chartered accountant and by 1898 had become an associate member of the Institute of Accountants and Actuaries in Glasgow.[10] In a 1938 paper written by Mann, "Measures: their prehistoric origin and meaning", he describes how he was "educated at the University of Glasgow as well as on the continent in his teens".[10]

Career

Insurance

It is likely that Ludovic Mann began his career as an accountant at his fathers business, John Mann and Sons, an insurance broker that was founded in 1886. His early career would have involved further training in accountancy, training in insurance.[11] and actuarial science. In 1899, Mann invented consequential loss insurance then called consequential fire loss indemnity. Losses were calculated based on the turnover of the previous year that preceded the damage.[12] They were essentially contracts of indemnity which would compensate for losses occurring during a period of reduced turnover following the damage.[12] In 26 January 1900, Mann patented his invention and marketed it through the Canadian Western Assurance Company office in Glasgow.[10] The product would be later known as Consequential Loss Insurance or Profits Insurance.[12] In December 1907, he became the manager of the company branch office in Glasgow[10] where he continued to develop innovative insurance products. By 1910, he was still advertising the product that he was selling from the office of Western Assurance at 144 St. Vincent Street, Glasgow.[13] By 1925, Mann had become senior partner in Mann, Ballantyne and Co, Insurance Administrators and Brokers. This was an insurance company that had offices in Glasgow and London.[14][b] By 1950, Mann was chairman of Mann and Ballantyne.[11][10]

Archeological research

Early career

In addition to his insurance endeavours, Mann had another great passion which was as an amateur archeologist, in essence an antiquarian. He was described as the original urban prehistorian.[16] Indeed, he was so involved in it, active between 1901 and 1945, that it could be called a secondary career, resulting in him becoming Scotland's most significant figure in the development of archeology.[16] It is unknown when or why Mann became interested in archeology, although it is known that by 1901 he was a Fellow of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland[10] but it was his membership of the Glasgow Archaeological Society that held his "first and abiding interest".[17] These dates are further clarified when Mann received a letter from the artist and amateur archeologist William Donnelly on 26 July 1903 congratulating him on "How pleased I was to see you occupying such a prominent position in the report in the “Herald” of your first find".[18][19] This was in response to Mann's first paper "Note on the finding of an urn, jet necklace, stone axe, and other associated objects, in Wigtownshire" of March 1902, where he discovered the remains of a stone axe-head and urn at a late Neolithic site at Mye Plantation in Stoneykirk, Wigtownshire.[20] The discoverer of the site, a Mr Beckett found 188 small pieces of finely-wrought lignite that was surmised by Mann as being part of a necklace.[20][21] Mann made further visits to the site, that eventually resulted in another much larger paper "Report on the Excavation of Pre-Historic Pile Structures in Pits in Wigtownshire"[22] Mann excavated three shallow depressions surrounded by wooden posts, that he considered to be some kind of pit-dwelling.[23] Other pits that were excavated were thought to be the remains of pit-falls for catching game.[21]

Mann's next paper in 1904, "Notes (1) on Two Tribula or Threshing-Sledges..."[24] was a description of a threshing sledge that he had found in Cavalla in Turkey, while on his travels.[25] This was a flat wooden board set with rows of chipped flint that was used to threshing corn.[25] Mann conducted an ethnographic analysis of similar devices and their use in various countries. Link to sites where chipped flint was found in the UK was described.[24] Other devices e.g. sickles are analysed.[25] In 1905, Mann attended a dig in Langside, Glasgow where he discovered several burial cinerary urns at a Bronze Age cemetery.[26] Mann's 1906 paper, "Notes on – (1) A drinking-cup urn found at Bathgate..."[27] describes finds in Bathgate and Stevenston that led to Mann visiting each site.[25] The second chapter describes a site that he found in Tiree that contained 18 cinerary urns.[c] The last chapter marshalled the current level of research on British prehistoric beads as it was in 1906.[27] A short paper followed in 1908 where he examined Craggan pottery[d] from Coll.[31]

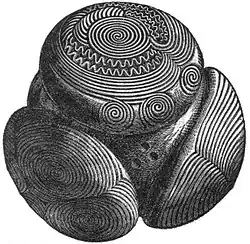

It was six years before Mann wrote another paper, the 1912 examination of perforated stones titled "Perforated Stones of Unknown Use", whose real use hadn't been determined at that point.[e][33] These perforated stones dated between the middle to late Neolithic periods were used amongst others uses as maceheads.[34] The 14 page report by Mann examined a number of stones from different finds in various countries but came to no firm conclusion as to their use.[33] Several examples of perforated stones from the collection of Andrew Henderson Bishop, an amateur archeologist and close friend of Mann were photographed for the paper.[35] In 1914, he examined a number of Carved stone balls that were found mainly in Scotland with a paper titled "The carved stone balls of Scotland: a new theory as to their use".[36] He concluded that they were used in a commercial activity as part of a system of weights.[35]

Dumbuck Crannog

In December 1902, Mann became involved in the Dumbuck Crannog controversy.[35][37] The Crannog was discovered in the north shore of Firth of Clyde, close to Dumbarton Castle by William Donnelly on 31 July 1898.[38] The crannog became notorious for the discovery of a number of forgeries[39] that had been liberally salted throughout the site.[40] These were discovered on 12 October 1898 by the physician, academic, archeologist and crannog specialist Dr Robert Munro who visited the site and made a number of excavations. He came to believe that the crannog itself was genuine but the finds, consisting of 30 stone and shale figurines with human characteristics, were elaborate forgeries.[41] Munro wrote a letter to the Glasgow Herald on 7 January 1899 confirming his belief, which led to a heated debate that played out in the Glasgow newspapers between 1900-1905 and local archeology societies.[42] Donnelly followed the debate in the newspapers for several months, before entering into private communication with Mann, the first of a number of letters exchanged between them, that began on 26 July 1903.[43] By December 1905 and the death of William Donnelly, the newspaper debate had completed.[43]

The controversy re-emerged in 1932, when Mann came to the conclusion that the artifacts were genuine.[44] He had examined them, taken their measurements and weights and concluded that they followed a prehistoric scale, known as the "metric test" where constructed objects used multiples of the units of 0.619 inch and 0.553 inch in their measurements.[44] In a letter to the Glasgow Herald on 27 April 1932, he concluded:

the so-called Clyde forgeries of 1898, not only in their dimensions but in their incised design, enshrine the method of combining the twin measures in a single relic … no faker of 1898 could possibly have known of these intricate matters, and thus the relics supposed by some to be forgeries must be genuine.[45]

The son of William Donnelly, Gerald Donnelly, welcomed the news, as it restored his father reputation. However, Mann's measurement scale was never accepted by mainstream archeologists.[45]

Exhibitions

Mann had a keen interest in raising public awareness of the early science of archaeology and particularly of his work.[35] This began in 1911, when he organised the prehistoric collection of the Scottish Historical Exhibition held as part of the Scottish Exhibition of National History, Art and Industry that was held in Glasgow[35] between 2 May to 4 November 1911. Mann provided many of his own pieces for the exhibition and also held a number of lectures under the heading "Glimpses of Scottish Pre-History".[35] Mann also wrote the introduction to the "Prehistoric Section" of the exhibition catalogue, that he used to critique the underfunding of Scottish archaeology research, stating:

The elucidation of Scottish Prehistory has been seriously handicapped by lack of funds (most Scottish subscriptions for archaeological research going abroad), by an ignorant and dogmatic dilettanteism, and an almost invariable wrecking of prehistoric structures and objects as they come to light. If the Prehistoric Gallery assists in substituting for a merely idle and antiquarian curiosity a strong, intelligent scientific interest, the labours of those who have devoted two years to the preparation of the Gallery, and a much longer time to the collection of its contents, will be amply repaid.[46]

In 1918, Mann organised his second exhibition, held at Langside Public Library in Langside, on objects and artefacts connected to the Battle of Langside and Mary, Queen of Scots.[47] Mann populated the exhibition with pieces from several sources including the Hamilton Palace and Pollok House collections along with local pieces and those from private individuals.[47] Mann wrote a book for the exhibition, the "Mary Queen of Scots at Langside, 1568"[48] with the profits going to the war relief fund.[47] As he built experience of forming and hosting exhibitions, he also gained experience of how to display ancient artefacts in the most effective manner.[47] As the size of his collection increased, he eventually found a permanent home in the Kelvingrove Museum, when the Prehistoric Room was opened in 1928.[47]

In 1932, Mann created an exhibition of pottery at the "Daily Mail Scottish Ideal Home Exhibition in Olympia, London, covering prehistoric pottery to Crogan Ware[f][47] From May 1938, Mann was heavily involved as an Archeological Observer for the Empire Exhibition in Bellahouston Park, Glasgow.[50] This was followed by a visit to San Francisco in 1939 to exhibit at the Golden Gate International Exposition.[51] He ensured the exhibition presented a replica of a Druid temple as well as a replica Robert Burns’ home in Alloway and of the Knappers dig. He also lectured on his most recent digs and finds. However, the exhibition was a financial failure that ended costing him money.[51]

Cambusnethan bog body

On 23 March 1932, a local Wishaw worker named Gerald Ronlink was digging peat in Greenhead Moss, when he came across a fully-clothed, partly-preserved body buried about two feet down in the bog.[52] The body was buried directly south of Cambusnethan Kirk[g] on unconsecrated ground, close of Watling Street, a former Roman road and the village of Overtown.[54] In the 18th Century, the village of Waterloo wouldn't have existed and bog would itself would have been a substantial size.[54]

Although the clothes were partially damaged, a unique jacket, cap, and leather shoes could be made out.[55] On 24 March, Mann arrived at the request of the prosecutor fiscal to examine the body, that had been moved to the local police station.[54] The day after, both the The Motherwell Times and the The Glasgow Herald reported that the body was a Covenanter soldier.[54]

The quality of Mann's investigative technique was in evidence as he formed his hypothesis of the man's identity.[4]

In 1933, Mann released a report on the body "Notes On The Discovery Of A Body In A Peat Moss At Cambusnethan"[55] that was read before the Glasgow Archaeological Society on 16 February 1933.[h][56]

Metrology

Metrology, the scientific study of measurement, was an already well-established antiquarian discipline[57] by the time Mann took an interest in it, in the early 1900's. For example, in 1728, the polyglot and scientist Isaac Newton (1643–1727) used the royal cubit that measured 20.7inches, to measure the circumference of the tomb at Abydos in Egypt. He believed it was built in a circle, measuring 365 cubits that represented days of the year.[57] In 1740, William Stukeley (1687–1765) had measured several English stone circles including Stonehenge and calculated the cubit at 20.8inches. Stukeley believed that the measurement had been brought to the UK from the East. There was no further interest in metrology in the UK for more than 80 years until the astronomer and Egyptologist, Charles Piazzi Smyth (1819–1900) measured the pyramids in 1874 and came to the conclusion that the measure was a "half a hair’s breadth" bigger than British inch, which he called the "Pyramid Inch" and believed that the pryamids builders must have been in contact with the ancestors of the Anglo-Saxons.[58] Mann's collaborator, the Egyptologist Flinders Petrie (1853–1942), whose father was an associate of Smyth, believed that ancient measurements systems that were lost could be recovered by measuring monuments in the present day and searching for commonalities that could lead to a standard measure. He measured more than 10,000 monuments in numerous countries. After measuring Stonehenge, he concluded that Stukeley's measure of 20.8 inches was incorrect, instead suggested that the real measure was roughly 4.7 inches.[59]

While Mann's fellow antiquarians were measuring monuments, Mann measured the artefacts that he had excavated from his own digs, that were made from bone, antler, stone and clay that were dated from the palaeolithic to the Iron Age and into the early Christian period.[59] In 1930, Mann formalised his research in the pamphlet "Craftsmen’s Measures and Ancient Measures"[60] where he stated:

Investigation of many thousands of objects has shown that drawings and carvings, and worked objects of bone, antler, stone, baked clay, glass, vitreous paste, and metal, of prehistoric, proto-historic, and even historic times, bear traces of having been made by craftsmen strictly disciplined to employ certain stereotyped, artificial, and unalterable units of length. … The writer has in addition examined many thousands of objects in the principal British, American and Continental museums. Relics belonging to every known archaeological field have been examined, including remote and now uninhabited Oceanic islands. Everywhere the same moduli and system of measurement have been traced. Thus to the enormous range of the system in time must be added its surprisingly wide range in territory. Prehistoric man had obviously to follow the dictates of a law stringently imposed upon the whole world.[61]

Mann believed he had discovered two fundamental units of measurements that were used in the ancient world.[62] The first, that he called the "Alpha unit" was a small measurement of 0.619 inches (15.72mm), the second which he called the "Beta unit" was even smaller at 0.55 inches (14.06 mm) long.[62][63] Mann presented 76 artefacts in Craftsmen’s Measures that he used to illustrate as examples.[63] Mann emphasised the need to measure the object correctly, measuring the dimensions at right-angles to each other, which could be done by placing them on a grid, stating "If … by a kind of guess-work method the object is measured in each of its dimensions, separately and independently, and without the guidance of a box-like rectangular figure, failure will usually occur".[63][64] Mann stated that ancient craftsmen use guages to ensure accuracy of measurement. According to Mann, one such guage had been recorded, i.e. incised on a tomb cover-stone in Kirkhouse, Strathblane.[65]

1933 Dispute

On 2 March 1933, Mann gave an address to the Glasgow University Geological Society titled "Crustal Pulsations and Palaeolithic Man in Scotland" where he discussed his theories on the metrology of ancient artefacts and his belief that they were made by humans. This was a controversial position to take at the time, as it was unknown whether, for example, eoliths were naturally occurring or designed by humans.[66] The talk was reported in the Glasgow Herald, the Scotsman and Express, which generated a significant amount of correspondence and that eventually generated into a bitter dispute between Mann and his archeological fellows on one side and Sir Edward Battersby Bailey who held the chair of geology at the University of Glasgow and his fellow geologists on the other side.[66]

To settle the matter and come to some kind of consensus, it was decided to established a 9-man committee of 4 members from each discipline.[66] The archeological contingent consisted of John M Davidson, James Grieve, Joe Harrison Maxwell and J. Jeffrey Waddell while the geologists consisted of William Roberts Flett, P. A. Leitch, James Phemister and S. J. Ramsay Sibbald with E.B. Bailey acting as chairman.[67] The group began measuring artefacts in November 1933 and continued until March 1937.[66] The committee released a report "Reports of the Joint Committee on Ancient Measures: Presented to the Glasgow Archaeological Society and The Geological Society of Glasgow" on 28 July 1937 that concluded by statistical analysis, that Manns measurements as a "percentage of fits was roughly the same as the percentage which would have occurred by chance over minus or positive 1mm".[68] That conclusion was supported by the four geologists but only one of the archeologists while the rest, Davidson, Maxwell and Waddell agreeing that the measurement methodology used during the investigation was flawed.[68] Mann responded to his critics in 1938 with a pamphlet, "Ancient Measures: their Origin and Meaning",[69] stating the "Lack of cohesion in the work of the Committee has been … disastrous, and the compilation of the measurements of some 150 artifacts over a period of more than 3½ years is eloquent testimony to its futility".[70]

Death

Mann died in his bedroom at his house in 4 Lynedoch Crescent in Glasgow.[5] In his will, he stipulated that his collection of prehistoric finds should remain in the public domain,[5] so they were bequeathed upon his death to the Kelvingrove Art Gallery and Museum then known as Glasgow Art Gallery and Museum.[71][72]

Publications

- Mann, Ludovic (1915). Archaic sculpturings. Notes on art, philosophy, and religion in Britain, 2000 B.C. to 900 A.D. London: William Hodge. OCLC 557481.

- Mann, Ludovic (1918). Mary Queen of Scots at Langside, 1568 (1st ed.). OCLC 11628239.

- Mann, Ludovic (1930). Craftsmen's measures in prehistoric times. Glasgow: Mann Pub. Co. OCLC 9487547.

- Mann, Ludovic (1937). An appeal to the nation:the "Druids" Temple near Glasgow A magnificent, unique and very Ancient Shrine in imminent danger of destruction. London: William Hodge and Company. OCLC 1036275694.

- Mann, Ludovic (1938). Earliest Glasgow A Temple of the Moon. Glasgow: Mann Publishing Company. OCLC 25376747.

- Mann, Ludovic (1938). Ancient Measures; their Origin and Meaning. Glasgow: Mann Publishing Company.

Notes

- ^ Consequential fire loss indemnity is a form of insurance to protect against a loss occurring from a fire as a result of being unable to use equipment within a commercial property.[2]

- ^ The 1922 edition of Who's Who has no entry for Mann indicating he was still working at the Western Assurance as a manager, at that point in time.[15]

- ^ The Iron Age material found by Mann was later discussed by the archeologist Euan MacKie in 1964.[28][25]

- ^ A roughhewn clay pot known as a Craggan found in Coll and Tiree.[29][30]

- ^ Richie lists the date of publishing as 1917 which is incorrect.

- ^ "Crogan Ware", also known as "Craggan Ware" is a particular type of Bronze and Iron age pottery that is associated with the Hebridean islands.[49]

- ^ Cambusnethan Parish Church was originally built c. 1650 and became a ruin in the 18th century and was replaced by the new kirk. The old church was located on the shore of Greenhead Moss at the top left corner.[53]

- ^ The report was republished in Transactions of the Glasgow Archaeological Society 1937.

References

Citations

- ^ Ritchie 2002, pp. 34–64.

- ^ "What is a consequential loss and can businesses insure against it?". Eddisons. Leeds. Retrieved 13 October 2024.

- ^ a b Brophy 2001.

- ^ a b Mullen 2020, p. 7.

- ^ a b c d e f Ritchie 2002, p. 45.

- ^ Previts & Bricker 2006, p. 240.

- ^ a b Eyre-Todd 1909, p. 140.

- ^ The Accountant 1910, p. 880.

- ^ a b Previts & Bricker 2006, p. 239.

- ^ a b c d e f Ritchie 2002, p. 46.

- ^ a b Who's Who. London: A. C. Black Limited. 1950. p. 1841.

- ^ a b c Eckles, Hoyt & Marais 2022, p. 8.

- ^ The Paisley Directory and General Advertiser. Paisley: J and J Cook Ltd. 1910. p. 6.

- ^ Who's Who 1925. London: A.C. Black Ltd. 1925. p. 1890.

- ^ Who's Who. London: A.C. Black Limited. 1922. p. 1784.

- ^ a b "A website and blog dedicated to Ludovic Mann". The Mann The Myth. Kenny Brophy, University of Glasgow. Archived from the original on 31 March 2025. Retrieved 31 March 2025.

- ^ "Death of Mr. L.M. Mann". Glasgow: George Outram & Co. The Glasgow Herald. 1 October 1955. p. 6.

- ^ Hale & Sands 2005, p. 53.

- ^ "Society of Antiquaries of Scotland". Glasgow: George Outram & Co. The Glasgow Herald. 12 May 1903. p. 10.

- ^ a b Mann 1902a, pp. 584–589.

- ^ a b Ritchie 2002, pp. 46–47.

- ^ Mann 1903, pp. 370–415.

- ^ "Mye Plantation". Canmore. Historic Environment Scotland. 24 November 2021. Retrieved 1 April 2025.

- ^ a b Mann 1904, pp. 506–519.

- ^ a b c d e Ritchie 2002, pp. 47.

- ^ Mann & Bryce 1905, pp. 528–552.

- ^ a b Mann 1906, pp. 369–402.

- ^ MacKie 1965, pp. 266–278.

- ^ Hollyman 1947, p. 204.

- ^ "Some Glimpses of the Prehistoric Hebrideans". Blackwood's Edinburgh Magazine. CXXXII (DCCCII). New York: Leonard Scott Publishing Company: 164–176. August 1882.

- ^ Mann 1908, pp. 326–329.

- ^ "Carved stone balls". Scottish Archaeological Research Framework. Edinburgh: Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, National Museums of Scotland. Retrieved 28 July 2025.

- ^ a b Mann 1912, pp. 289–297.

- ^ "Special' stone artefacts". Scottish Archaeological Research Framework. Edinburgh: Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, National Museums of Scotland. 10 August 2015. Retrieved 19 May 2025.

- ^ a b c d e f Ritchie 2002, p. 48.

- ^ Mann 1914, pp. 407–420.

- ^ Mann 1902b, p. 9.

- ^ Hale & Sands 2005, p. 16.

- ^ Hale & Sands 2005, p. 4.

- ^ Hale & Sands 2005, p. 57.

- ^ Hale & Sands 2005, p. 48.

- ^ Hale & Sands 2005, pp. 48–55.

- ^ a b Hale & Sands 2005, p. 54.

- ^ a b "'Queer things' afoot on banks of Clyde". The Scotsman Publications Ltd. The Scotsman. 8 October 2005. Retrieved 23 June 2025.

- ^ a b Hale & Sands 2005, p. 55.

- ^ Scottish Exhibition of National History, Art, & Industry Glasgow (1911) Palace of History CATALOGUE OF EXHIBITS. Vol. II. Glasgow: Dalross Ltd. 1911. pp. 809–810.

- ^ a b c d e f Ritchie 2002, p. 50.

- ^ Mann 1918b.

- ^ Cheape 2010.

- ^ Ritchie 2002, pp. 50–51.

- ^ a b Ritchie 2002, p. 51.

- ^ Mullen 2020, p. 2.

- ^ "Cambusnethan Parish Church". Buildings at Risk. Edinburgh: Historic Environment Scotland. 28 March 2008. Retrieved 28 July 2025.

- ^ a b c d Mullen 2020, p. 3.

- ^ a b Mann et al. 1937c.

- ^ Mann et al. 1937c, p. 44.

- ^ a b Henty 2020, p. 53.

- ^ Henty 2020, p. 54.

- ^ a b Henty 2020, p. 55.

- ^ Mann 1930.

- ^ Mann 1930, pp. 1–2.

- ^ a b Henty 2020, p. 57.

- ^ a b c Behrend 1977.

- ^ Mann 1938, p. 9.

- ^ Mann 1938, p. 8.

- ^ a b c d Henty 2020, p. 58.

- ^ Henty 2020, p. 59.

- ^ a b Henty 2020, p. 60.

- ^ Mann 1938.

- ^ Mann 1938, p. 3.

- ^ Ritchie 2002, p. 1.

- ^ "Ludovic Mann". Future Museum South West Scotland. Future Museum Project Partners. Archived from the original on 13 October 2024. Retrieved 13 October 2024.

Bibliography

- The Accountant. Vol. 43. London: Gee and Co. December 1910.

- Behrend, Michael (1977). "A Forgotten Researcher: Ludovic Mclellan Mann". Journal of Geomancy and Ancient Mysteries. Cambridge: Institute Of Geomantic Research, University of Cambridge. ISSN 0308-1966.

- Brophy, Kenny (8 February 2001). "Ludovic McLellan Mann: Glasgow's original media influencer". Edinburgh University Press. Edinburgh. Archived from the original on 19 June 2024. Retrieved 13 October 2024.

- Brophy, Kenneth (October 2020). "The Ludovic technique: the painting of the Cochno Stone, West Dunbartonshire". Scottish Archaeological Journal. 42 (Supplement): 85–100. doi:10.3366/saj.2020.0148.

- Brophy, Kenneth (14 September 2016). "Raiders of the lost marks: how we uncovered the mysterious prehistoric rock art of the Cochno stone". The Conversation. Glasgow: University of Glasgow. Archived from the original on 8 November 2020. Retrieved 20 January 2025.

- Cheape, Hugh (1 July 2010). "A cup fit for the king': literary and forensic analysis of crogan pottery" (PDF). Department of Archaeology. Glasgow: University of Glasgow, Society of Antiquaries. Retrieved 30 June 2025.

- Eyre-Todd, George (1909). Who's who in Glasgow in 1909 : a biographical dictionary of nearly five hundred living Glasgow citizens and of notable citizens who have died since 1st January, 1907. Glasgow: Gowans & Gray. p. 140. OCLC 21471969.

- Eckles, David L.; Hoyt, Robert E.; Marais, Johannes C. (2022). "The history and development of business interruption insurance" (PDF). Journal of Insurance Regulation: 1–35. doi:10.52227/25540.2022.

- Hale, Alex; Sands, Rob (2005). Controversy on the Clyde Archaeologists, Fakes and Forgers: The Excavation of Dumbuck Crannog. Glenrothes: Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Scotland. ISBN 1-902419-45-6.

- Henty, Liz (October 2020). "Ludovic McLellan Mann's place in the history of prehistoric metrology". Scottish Archaeological Journal. 42 (Supplement): 52–64. doi:10.3366/saj.2020.0145.

- Hollyman, G.A. (December 1947). "Tiree Craggan's". Antiquity. XXI (84): 204.

- MacKie, Euan W. (December 1965). "Brochs and the Hebridean Iron Age". Antiquity. 39 (156): 266–278. doi:10.1017/S0003598X00039648.

- Mann, LJM (10 March 1902a). "Note on the Finding of an Urn, Jet Necklace, Stone Axe, and other Associated Objects, in Wigtownshire". Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland. 36: 584–589. doi:10.9750/PSAS.036.584.589.

- Mann, Ludovic (12 December 1902b). "These Eternal Crannog". Glasgow: George Outram & Co. The Glasgow Herald. Retrieved 23 June 2025.

- Mann, Ludovic McLellan (30 November 1903). "Report on the Excavation of Pre-Historic Pile Structures in Pits in Wigtownshire". Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland. 37: 370–415. doi:10.9750/PSAS.037.370.415.

- Mann, Ludovic McLellan (30 November 1904). "Notes (1) on Two Tribula or Threshing-Sledges, having their under surfaces studded with rows of chipped flints, for threshing corn on a threshing-floor, from Cavalla in European Turkey, now presented to the Museum; and (2) on Primitive Implements and Weap". Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland. 38: 506–519. doi:10.9750/PSAS.038.506.519.

- Mann, Ludovic McLellan; Bryce, Thomas (30 November 1905). "Notes on the Discovery of a Bronze Age Cemetery, containing Burials with Urns, at Newlands, Langside, Glasgow". Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland. 39: 528–552. doi:10.9750/PSAS.039.528.552.

- Mann, Ludovic McLellan (30 November 1906). "Notes on (1) A Drinking-cup Urn found at Bathgate; (2) the Exploration of the Floor of a Pre-historic Hut in Tiree; and (3) a Group of (At least) Sixteen Cinerary Urns found, with objects of Vitreous Paste and of Gold, in a Cairn at Stevenston, Ayrshire". Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland. 40: 369–402. doi:10.9750/PSAS.040.369.402.

- Mann, Ludovic McLellan (30 November 1908). "Notices (1) of a Pottery Churn from the Island of Coll, with Remarks on Hebridean Pottery; and (2) of a Workshop for Flint Implements in Wigtownshire". Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland. 42: 326–329. doi:10.9750/PSAS.042.326.329.

- Mann, Ludovic Maclellan (1912). "Perforated Stones of Unknown Use". Transactions of the Glasgow Archaeological Society. 6 (2): 289–297. ISSN 2398-5755. JSTOR 24681398.

- Mann, Ludovic MacLellan (30 November 1914). "The Carved Stone Balls of Scotland: A New Theory as to their Use". Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland. 48: 407–420. doi:10.9750/PSAS.048.407.420.

- Mann, Ludovic McLellan (1915a). Shirley, G. W. (ed.). "The Archaic Sculpturings of Dumfries and Galloway; being chiefly Interpretations of the Local Cup and Ring Markings, and of the Designs on the Early Christian Monuments" (PDF). Transactions and Journal of Proceedings 1914-15. III (3). Dumfries: Dumfriesshire And Galloway Natural History & Antiquarian Society: 121–166.

- Mann, Ludovic McLellan; Scott, A; Petrie, W M Flinders (30 November 1918a). "The Prehistoric and Early Use of Pitchstone and Obsidian: With Report on Petrology; and a Note of Egyptian and Aegean Discoveries". Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland. 52: 140–149. doi:10.9750/PSAS.052.140.149.

- Mann, Ludovic MacLellan (1918b). Mary Queen of Scots at Langside, 1568. Glasgow. OCLC 11628239.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Mann, Ludovic MacLellan (30 November 1922). "Ancient Sculpturings in Tiree". Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland. 56: 118–126. doi:10.9750/PSAS.056.118.126.

- Mann, Ludovic McLellan (30 November 1923). "Bronze Age Gold Ornaments found in Arran and Wigtownshire, with Suggestions as to their Method of Use". Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland. 57: 314–320. doi:10.9750/PSAS.057.314.320.

- Mann, Ludovic (1930). Craftsmen's measures in prehistoric times. Glasgow: Mann Pub. Co. OCLC 9487547.

- Mann, Ludovic Mac (1937a). An Appeal to the Nation: The "Druids' " Temple near Glasgow A magnificent, unique and very Ancient Shrine in imminent danger of destruction. Glasgow: William Hodge and company, limited. OCLC 499297767.

- Mann, Ludovic; Graham, John; Eskdale, Robert G.; Martin, William (1937b). "Notes on the Discovery of a Body in a Peat Moss at Cambusnethan". Transactions of the Glasgow Archaeological Society. 9 (1): 44–55. ISSN 2398-5755. JSTOR 24680631.

- Mann, Ludovic; Graham, John; Eskdale, Robert G.; Martin, William (1937c) [16 February 1933]. "Notes on the Discovery of a body in a peat moss at Cambusnethan". Transactions of the Glasgow Archaeological Society. 9 (1): 44–55. JSTOR 24680631.

- Mann, Ludovic MacLellan (1939). The Druid Temple Explained. Being a set of talks on folklore, myths, and prehistoric religion (4th ed.). Glasgow. OCLC 561871006. Archived from the original on 1 July 2025.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Mann, Ludovic (1938). Ancient Measures; their Origin and Meaning. Glasgow: Mann Publishing Company.

- Mann, Ludovic MacLellan (1939). Earliest Glasgow a temple of the moon : an outline of early science and religion. Glasgow: Mann Publishing Company. OCLC 25376747.

- Mearns, Jim (October 2020). "Mann makes himself: Ludovic Mann and the media". Scottish Archaeological Journal. 42 (Supplement): 65–70. doi:10.3366/saj.2020.0146.

- Mullen, Stephen (October 2020). "Ludovic McLellan Mann and the Cambusnethan bog body" (PDF). Scottish Archaeological Journal. 42 (Supplement): 71–84. doi:10.3366/saj.2020.0147.

- Previts, Gary J.; Bricker, Robert (12 April 2006). Seekers of Truth: The Scottish Founders of Modern Public Accountancy. Emerald Group Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7623-1298-6.

- Ritchie, J N Graham (2002). "Ludovic McLellan Mann (1869-1955)". Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland. 132: 43–64. doi:10.9750/PSAS.132.43.64.

.jpg)

_(14784212442).jpg)

_(14782207564).jpg)