Patrick Gibson, Baron Gibson

The Lord Gibson | |

|---|---|

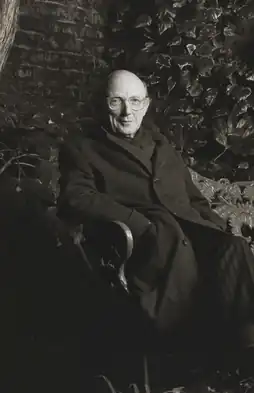

Lord Gibson photographed by Lord Snowden in 1988 | |

| Born | Richard Patrick Tallentyre Gibson February 5, 1916 Kensington, London, England[1] |

| Died | April 20, 2004 (aged 88) |

| Nationality | British |

| Education | Eton College[1] |

| Alma mater | Magdalen College, Oxford[1] |

| Occupation(s) | Businessman and arts administrator[1] |

| Employer(s) | Pearson plc; Financial Times Ltd; Arts Council of Great Britain; National Trust[1][2] |

| Known for | Chair of the Arts Council of Great Britain and of the National Trust; Chairman of Pearson plc[1][2] |

| Title | Life peer as Baron Gibson[3] |

| Spouse |

Dione Pearson (m. 1945–2004) |

| Children | 4 sons[1] |

| Military career | |

| Allegiance | United Kingdom |

| Branch | British Army |

| Unit | Middlesex Yeomanry |

| Battles / wars | North African campaign; Italian campaign |

Richard Patrick Tallentyre Gibson, Baron Gibson (5 February 1916 – 20 April 2004) was a British publishing executive and arts administrator.[1] He chaired the Arts Council of Great Britain from 1972 to 1977[4] and the National Trust from 1977 to 1986.[1][2] In business he was group chairman of Pearson plc from 1978 to 1983 and chairman of Financial Times Ltd from 1975 to 1977.[1][2]

Early life and war service

Gibson was educated at Eton and Magdalen College, Oxford. His parents were both accomplished singers, his father a former professional baritone and his mother a lieder recitalist, and he later said he would have liked to be an orchestral conductor.[1][2]

He joined the Middlesex Yeomanry in 1939 and served in the North African campaign, being taken prisoner at Derna in Libya in April 1941.[5][2] He was held for two years in prisoner-of-war camps in northern Italy, including at Fontanellato near Parma.[5][2]Camp PG 49 at Fontanellato occupied a former orphanage and held about 500 Allied officers and 100 other ranks.

After the Italian Armistice in September 1943 the commandant of Camp PG 49, Colonel Eugenio Vicedomini, warned that German forces were approaching and told prisoners to leave; the inmates then dispersed into the countryside.[6] Colonel Eugenio Vicedomini was sent to a German concentration camp for opening the gates of the camp. [7]

The prisoners dispersed into the countryside ahead of approaching German forces, many heading either south towards Allied lines or north towards Switzerland; local civilians provided food, shelter and clothing. Gibson travelled south with Edward Tomkins and Hugh Cruddas.[6] They were helped by local civilians with food and occasional clothing.[6] In one village, a shopkeeper, on seeing a maternal inscription on Gibson’s watch, refused the watch as payment and supplied food for free.[6] The men moved south from the Po river to Bari, crossing the Apennines and German lines and reaching Allied territory after 81 days.[8][6] They reached Allied lines on the Sangro in the Abruzzi.[6]

Back in Allied hands, he returned to Britain and was seconded to the Special Operations Executive’s Italian section.[1][2][6] In 1944 to 1945, he served in Italy supporting partisan operations, then in 1945 to 1946 worked in the Foreign Office’s Political Intelligence Department.[1][2][6]

Pearson and the Financial Times

After the war, Gibson joined the Pearson family’s Westminster Press group in 1947, toured its provincial papers and became a director in 1948; in time he joined the boards of the Financial Times, The Economist and Pearson plc.[1] He chaired Pearson Longman from 1967 to 1979, chaired Financial Times Ltd from 1975 to 1977, and was group chairman of Pearson plc from 1978 to 1983.[1][2]

As Pearson’s group chairman from 1978, he led the move for the FT to begin printing in Germany; the Frankfurt European edition started on 2 January 1979, the paper’s first overseas print site.[1][9][10]

Within Pearson he backed diversification into visitor attractions. Just before becoming group chairman he pushed the takeover of Madame Tussauds and then gave its management responsibility for Chessington; in 1979 Pearson also took a stake in a US theme-park operator, groundwork that later helped the group buy and run Alton Towers.[1][11]

During the industrial conflicts of the 1970s he opposed a journalists’ closed shop, leading to a six-month strike at the Northern Echo.[11]

The Telegraph later described his style as strategic and unobtrusive, noting that he ran Pearson “from an eyrie in the Millbank Tower” and was sometimes dubbed “Cowdray’s Viceroy”.[5]

Arts Council of Great Britain

Gibson was appointed chair of the Arts Council of Great Britain in 1972, succeeding Arnold Goodman under the Conservative government of Edward Heath. Contemporary accounts link his selection to the arts brief held by Lord Eccles.[5] His tenure coincided with high inflation, pay pressures and rising expectations for wider access to culture.[1][4] A later assessment in the Financial Times characterised the structural tension of the period as “insufficient funds to sustain the national ‘centres of excellence’ just as it came under pressure to increase funding for the regions”.[12]

Working with Labour arts minister Hugh Jenkins from 1974 to 1976, the Council backed a stronger role for the Regional Arts Associations (RAAs). Jenkins told the Commons that the Arts Council would “continue to give a high priority” to supporting the associations.[13] In a 1977 Lords debate Gibson reviewed the period, noting early progress on touring and regional funding, followed by constraint after the 1973–74 economic crisis and high inflation.[14]

The Council also considered proposals to rationalise major companies. Press coverage at the time recorded Treasury interest in merging the Royal Opera House and English National Opera; the Council did not proceed and maintained support for both.[5]

In November 1973 the Council established a Community Arts Working Party, chaired by Professor Harold Baldry, to review support for participatory, locally based activity.[15] Following its report, the Council created a Community Arts Committee in April 1975 “for a two-year experimental period”, routing much support through the RAAs;[16] the 1976–77 report stated that community arts had “proved their worth and deserve continuing support at a higher level of subsidy”.[4]

Debate about elitism and access persisted. On 15 March 1974 Jenkins told the Commons he was working with trustees on ending museum admission charges, signalling the government’s priorities on access.[17] Gibson defended continued government funding of established institutions and supported spreading access to all for free, particularly those living in regions outside of London.[5]

Gibson’s chairmanship ended in 1977. By then the regional framework had been strengthened, a community-arts committee was in place, and the Council was restating accountability at arm’s length: “The Arts Council is the major source of arts patronage in Great Britain. It spends taxpayers’ money, and this lays on it a duty to exercise its patronage with responsibility…”.[4][18]

National Trust

Gibson chaired the National Trust from 1977 to 1986.[1][2] Membership passed the one million mark in 1980 and continued to rise through the decade.[2] Before becoming chair he had served on the Trust’s executive committee from 1963 and sat on Sir Henry Benson’s 1968 review of the Trust’s management and responsibilities.[2] Major properties coming to the Trust during his chairmanship included Studley Royal Park, Belton House, Calke Abbey and parts of The Argory estate, and contemporary accounts also credit him with helping to secure places such as Ightham Mote, Kinder Scout and Wenlock Edge.[2][12]

In 1983 he chaired an extraordinary general meeting at Wembley requisitioned by members who opposed granting a lease of underground rights beneath the Trust’s Bradenham estate in the Chilterns for an extension to the Ministry of Defence’s Cold War communications and operations facility associated with RAF High Wycombe. After debate a large majority endorsed the Council’s policy; press accounts recorded an attendance of about 8,000.[2][12] In the House of Lords he explained why the Trust’s statutory power of inalienability is central to such decisions: land declared inalienable cannot be sold and is protected from compulsory purchase except by special parliamentary process. He called that protection “an asset uniquely conferred on the trust by Parliament, and … the basis of the trust’s whole existence”, and argued that a tightly conditioned lease of subsurface rights, with minimal surface works and full restoration, preserved the Trust’s inalienable ownership and amenity better than reliance on compulsory powers.[19]

Other public roles

He served as chairman of the advisory council of the Victoria and Albert Museum, as a director of the Royal Opera House, as a trustee of Glyndebourne, as a member of the executive committee of the National Art Collections Fund, and as an adviser to the Gulbenkian Foundation.[2]

Personal life

In 1945 Gibson married Dione Pearson, granddaughter of Weetman Pearson, 1st Viscount Cowdray. They had four sons.[1] He took his title from his home Penn's Rocks in East Sussex, where he died on 20 April 2004.[3][2] A Daily Telegraph obituary noted a second home, an 18th century villa at Asolo near Venice.[5] A lifelong concert-goer, “his great love was for music”, and he attended Der Rosenkavalier with his family in the week before he died; he was still skiing in his eighties.[2]

Arms

|

|

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u Roth, Andrew (6 May 2004). "Lord Gibson". The Guardian. Retrieved 9 August 2025.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s Drury, Martin (26 April 2004). "Lord Gibson: Businessman and authoritative chairman of the Arts Council and the National Trust". The Independent. Retrieved 9 August 2025.

- ^ a b "No. 46484". The London Gazette. 4 February 1975. p. 1565.

- ^ a b c d "Arts Council of Great Britain: Thirty-second annual report and accounts 1976–77" (PDF). Arts Council of Great Britain. 1977. Retrieved 9 August 2025.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Lord Gibson". The Daily Telegraph. 21 April 2004. Retrieved 9 August 2025.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Set Europe Ablaze: oral history interview (1983)". Imperial War Museums. Retrieved 9 August 2025.

- ^ "Leaving the Italian prisoner of war camp Fontanellato". The National Archives (UK) Blog. The National Archives. 8 September 2016. Retrieved 9 August 2025.

- ^ "Sir Edward Tomkins". The Daily Telegraph. 25 September 2007. Retrieved 9 August 2025.

Subsequently he and Gibson walked down Italy, from the Po to Bari, finally reaching safety after 81 days.

- ^ "Financial Times Europe, Frankfurt branch: library record". Dartmouth College Library. Retrieved 9 August 2025.

Frankfurt/Main… began with No. 27,753 (Tuesday, Jan. 2, 1979).

- ^ David Kynaston. "A brief history of the Financial Times". Gale. Retrieved 9 August 2025.

Printing in New York from 1985, as well as London and Frankfurt.

- ^ a b "Lord Gibson: Unwilling stockbroker and redoubtable soldier who became chairman of the Arts Council, the Pearson group and the National Trust". The Times. 22 April 2004. Retrieved 9 August 2025.

- ^ a b c Owen, Geoffrey; Angus Stirling (24 April 2004). "Man of formidable knowledge and fine taste". Financial Times.

- ^ "Regional Arts Associations". Hansard. 2 April 1974. Retrieved 9 August 2025.

- ^ "The Arts in England and Wales". Hansard. 15 June 1977. Retrieved 9 August 2025.

- ^ "The Arts Council of Great Britain: Twenty-ninth annual report and accounts 1973–1974" (PDF). Arts Council of Great Britain. 1974. p. 28. Retrieved 9 August 2025.

- ^ "The Arts Council of Great Britain: Thirty-first annual report and accounts 1975–1976" (PDF). Arts Council of Great Britain. 1976. Retrieved 9 August 2025.

- ^ "Museums and Galleries (Admission Charges)". Hansard. 15 March 1974. Retrieved 9 August 2025.

- ^ "The Arts Council of Great Britain: Thirty-fourth annual report and accounts 1978–1979" (PDF). Arts Council of Great Britain. 1979. Retrieved 9 August 2025.

- ^ "Naphill: Proposed Underground Operations Centre". Hansard. UK Parliament. 25 March 1982. Retrieved 9 August 2025.

Inalienability is "an asset uniquely conferred on the trust by Parliament, and … the basis of the trust's whole existence".

- ^ Debrett’s Peerage and Baronetage 2003. Debrett’s. 2003. p. 639.