List of Shakespearean settings

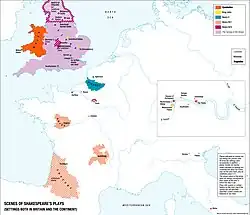

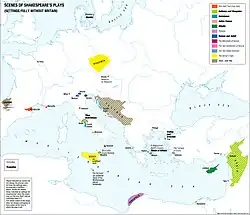

This is a list of the settings of Shakespeare's plays. Included are the settings of 38 plays, being the 36 plays contained in the First Folio, and Pericles, Prince of Tyre and The Two Noble Kinsmen.

Places mentioned in Shakespeare's[a] text are not listed unless he explicitly set at least one scene there, even where that place is important to the plot such as Syracuse in The Comedy of Errors or Milan in The Tempest. Similarly, the place where an historical or mythical event depicted by Shakespeare is supposed to have happened is not listed unless Shakespeare mentions the setting in the play's text, although these places are sometimes mentioned in the text or footnotes. For example, some editors have placed act 3 scene 2 of Julius Caesar at "the Forum" but there is no listing for the Forum on this page because Shakespeare's text does not specify it.

Contents:

Nations, cities and towns:

A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | Y

Less-specific settings

More-specific settings

References

Nations, cities and towns

A

- Actium in Greece is the location of Antony's and Cleopatra's preparations for the Battle of Actium, and of the sea battle's spectators, in Antony and Cleopatra.[1][2][3]

- Alexandria:

- See also "Cleopatra's Monument" under more-specific settings below.

- Alexandria in Egypt is the setting of the greatest number of scenes in Antony and Cleopatra. Also a number of scenes are set outside its walls, and in the camp of the Romans attacking it.[4][5][6]

- Angiers (Angers in France) and the camps and battlefields in its vicinity, especially the pavilion of the French king, are the settings of the second and third acts of King John.[7][8][9]

- Antioch in modern-day Turkey - but in the play referred to as located in Syria - is the setting of the opening scene, with its incest sub-plot, in Pericles.[10][11][12]

- Antium in present-day Italy is the Volscian city to which the banished Coriolanus travels to forge an alliance with Aufidius, in Coriolanus, and is the setting of the play's climax.[13][14]

- Athens:

- See also "Forest" under less-specific settings, below.

- Athens in modern-day Greece is the setting of a short scene between Antony and his new wife Octavia, in Antony and Cleopatra. [15][16][17][18]

- Athens in modern-day Greece, but in the world of the play a city-state governed by a duke - and a forest outside its walls - are the settings of A Midsummer Night's Dream.[19][20][21][22]

- Athens in modern-day Greece - and a forest outside its walls - are the settings of Timon of Athens.[23][24][25]

- Athens in modern-day Greece, but in the world of the play a city-state governed by duke Theseus accompanied by his wife Hippolyta, is the primary setting of The Two Noble Kinsmen.[26][27]

B

- Barnet in England is the site of the Battle of Barnet, at which Warwick died, and which is dramatized in Henry VI, Part 3.[28][29]

- Belmont is a fictional estate some twenty miles from Venice, Italy: the home of Portia and her household, and the setting of the "casket" scenes, and of the play's conclusion, in The Merchant of Venice.[30][31][32][33]

- For Berkeley see "Berkeley Castle" under more-specific settings below.

- For Berwick see the "England" entry for Henry VI, Part 3.

- Bohemia, the landlocked modern-day Czechia, is, in The Winter's Tale, a coastal kingdom of which Polixenes is the king. It is the setting of the end of Act 3 and the whole of the long act 4.[34][35][36]

- Bordeaux in France is the setting of the defeat of Talbot, and of the deaths of him and his son John, in Henry VI, Part 1.[37][38][39] In two related parallel scenes without specific locations, York and his army, then Somerset and his army, fail to send reinforcements to Talbot.[b]

- Bosworth, site of the battle of Bosworth Field, including the camps of both armies, and the tents of the leaders Richmond and Richard, are the settings of the climactic scenes of Richard III.[40][41][42]

- For Bristol see "Bristol Castle" under more-specific settings below.

- Britain:

- See also "England", "Scotland" and "Wales".

- Britain in the Roman era is the primary setting of Cymbeline. Shakespeare does not locate King Cymbeline's court any more precisely.[43][44][45]

- Britain in the pre-Christian era is the only setting of King Lear. In the world of the play the only location specified is Dover. The other significant settings (the homes of Lear, of Goneril and Albany, and of Gloucester, and the various outdoor settings) are not identified any more specifically.[46][47]

- For Bury St Edmunds see "St Edmundsbury".

C

- Corioli (typically spelled Corioles in the First Folio) - in modern-day Italy, although its precise location is unknown - and the battlefield and the trenches of the Romans attacking it, are the settings of the scenes in which Caius Martius earns the honorary name "Coriolanus", in Coriolanus.[48][49][50][51]

- Coventry:

- Coventry in England is the setting of the lists at which Mowbray and Bolingbroke are scheduled to fight in Richard II.[52][53]

- Near Coventry, in England, Falstaff delivers a soliloquy about his abuse of the King's press, in Henry IV, Part 1.[54][55][56][57]

- Coventry in England is the setting of Clarence's defection back to Edward's party, in Henry VI, Part 3.[58][59]

- Cyprus is the setting of the last four acts of Othello. No specific town or city within Cyprus is mentioned.[60][61][62]

D

- For Denmark see "Elsinore".

- Dover and various places in its vicinity, including the camps of the French and British armies nearby, are settings in the latter half of King Lear.[63][64][47][65]

E

- Elsinore:

- See also "Graveyard" under less-specific settings, below.

- Elsinore (i.e. Helsingør in Denmark), particularly its castle and its environs, are the only settings of Hamlet. The only scenes outside the castle are one on the Danish coast (act 4 scene 4) where Hamlet sees the Norwegian forces, and one set in a graveyard (act 5 scene 1).[66][67][68][69]

- England:

- See also "Windsor", and, under less-specific settings, below, "Castle", and, under more-specific settings below, "Forest of Arden", "Herne's Oak" and "Swinstead Abbey".

- See also "English Court" under more-specific settings below.

- The frame story of The Taming of the Shrew (i.e. the two scenes of the "Induction" and a short exchange at the end of act 1 scene 1), in which the drunken tinker Christopher Sly is persuaded he is a lord and is invited to watch a play, has no specified setting, but appears to be in England since Sly claims to be from Burton Heath,[70] Warwickshire, and to know a "fat alewife of Wincot".[71][72]

- England, probably at the court of Edward the Confessor, is the setting of a lengthy scene in which Malcolm tests Macduff's loyalty, and then Macduff learns of the murder of his family, in Macbeth.[73][74][75]

- England, somewhere near the border by Berwick (which was, at the time the play is set, in Scotland), King Henry visits his former dominions, and is captured by two keepers, in Henry VI, Part 3.[76][77][78]

- "England" is the only location given in a stage direction in Henry VI, Part 3, presumably to clarify the location since the scene (act 4 scene 2) includes French soldiers. Neither it nor the following scene, in which Warwick's powers overcome Edward's guards at his tent and take him prisoner, is given any more specific location.[79][80]

- Ephesus:

- Ephesus, in modern-day Turkey, but in the play a city state governed by a Duke, is the only setting of The Comedy of Errors.[81][82][83]

- Ephesus, in modern-day Turkey, is the scene of Thaisa's rescue by Cerimon, and later of Thaisa's reconciliation with Pericles at Diana's temple, in Pericles.[84][11][85]

F

- Fife in Scotland is the home of Lady Macduff and her children, and the setting of their murders in act 4 scene 2 of Macbeth.[86][87]

- Florence, in modern-day Italy but in the play an independent state governed by a duke, is the place to which Bertram runs away to take part in the Tuscan Wars, in All's Well That Ends Well, and is the setting of the gulling of Paroles, and of the bed-trick played upon Bertram by Helen and Diana.[88][89][90]

- Forres in Scotland is the site of Duncan's court in the early part of Macbeth.[91][92]

- France:

- See also "Angiers" and, under less-specific settings, below, "Castle", and, under more-specific settings below, "Forest of Arden" and "French Court".

- France is the location of As You Like It. The location of the scenes in Duke Frederick's court, and at Oliver's house, are not specified any more accurately.[93][94][95]

- France is the location of most of the last four acts of Henry V. Some scenes are not located more specifically, but occur on the march between Harfleur and Calais.[96][97][98]

G

H

- Harfleur in France is the setting of the Siege of Harfleur, dramatized in the third act of Henry V.[99][100]

- For Harlech see "Wales".

- For Helsingør see "Elsinore".

- For Higham see "Gad's Hill" under more-specific settings below.

I

- Illyria, a coastal region on the eastern Adriatic sea, including parts of modern-day Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Montenegro and Albania, is the only setting of Twelfth Night.[101][102]

- Inverness in Scotland is the location of Macbeth's castle prior to his becoming king, and is the setting of the events surrounding the murder of Duncan, in Macbeth.[103][104]

J

K

- For Kenilworth see "Kenilworth Castle" under more-specific settings below.

- For Kimbolton see "Kimbolton Castle" under more-specific settings below.

L

- London:

- See also "English Court" under more-specific settings below.

- London and Kent provide a series of settings for the rebellion of Jack Cade and its aftermath, dramatized in Henry VI, Part 2. Among the locations speculated by editors from clues in the text or from historical sources, but not explicitly stated by Shakespeare, are Blackheath, Sevenoaks, Cannon Street and Smithfield. The home of Alexander Iden, who captures and kills Jack Cade, has been placed in the counties of Sussex or Kent. [c][106] See also "Tower of London" and "Southwark" under more-specific settings below.

M

- Mantua in present-day Italy is the city to which Romeo flees when exiled in Romeo and Juliet, where he hears of Juliet's supposed death and purchases the poison which will eventually kill him.[107][108][109]

- Marseille, in France, is the setting of a short scene in All's Well That Ends Well. Helen, Diana and the Widow have followed the King there, only to learn that he has moved on to Roussillon.[110][111][112]

- Messina:

- See also "Pompey's Court" under more-specific settings below.

- Messina, on Sicily in modern-day Italy is the only location of Much Ado About Nothing[113][114]

- Milan:

- See also "Forest" under less-specific settings, below.

- Milan in modern-day Italy, but in the play governed by a duke, is the setting of most of the action of The Two Gentlemen of Verona.[115][116][117]

- Milford Haven in Wales, and the area surrounding it, are the settings of most of the second half of Cymbeline, including the cave of Belarius, the site of the battle between Rome and Britain, and the denouement at Cymbeline's camp.[118][119]

- Mytilene on Lesbos in modern-day Greece is the location of the brothel to which Marina is sold, and is the setting (together with Pericles' ship, while moored there) of much of the last two acts of Pericles.[120][121][122]

N

- For Naples see "Pompey's Galley" under more-specific settings, and "Sea" under less-specific settings, below.

- Navarre in present-day Spain but in the play an independent kingdom whose fictional king, Ferdinand, is one of the central characters, is the only setting of Love's Labour's Lost.[123][124][125]

O

- Orleans in France is the site of the first conflict between Joan and Talbot in Henry VI, Part 1.[126][127][39]

P

- Padua in modern-day Italy is the primary setting of The Taming of the Shrew.[128][129][130][131]

- Paris:

- See also "French Court" under more-specific settings below.

- Paris, in France, is the setting of the court scenes of All's Well That Ends Well.[132][133]

- Paris in France is the setting of Henry VI's coronation and the events surrounding it in Henry VI, Part 1.[134][135]

- Parthia at its border with the Roman Empire in modern-day Syria, Iran or Iraq is the scene of Ventidius' victory over Pacorus, in Antony and Cleopatra.[136][137][138]

- Pentapolis in modern-day Libya is the setting of the middle-part of Pericles, where the title character is shipwrecked, and meets his wife Thaisa.[139][140][141]

- Philippi, in Macedonia in present-day Greece, is the site of the Battle of Philippi which forms the action of the fifth act of Julius Caesar.[142][143][144][145]

- For Pontefract see "Pomfret Castle" under more-specific settings below.

Q

R

- Rochester:

- See also "Gad's Hill" under more-specific settings below.

- Rochester in Kent, England, is the setting of a scene in an inn yard in Henry IV, Part 1 in which the Gad's Hill robbery is planned.[146][147]

- Rome:

- See also "Capitol" under more-specific settings and "Forest" under less-specific settings, below.

- Rome in modern-day Italy is the secondary setting of Antony and Cleopatra, contrasted throughout the play with Alexandria.[148][149]

- Rome in modern-day Italy, and later in the play the camp of the Volscian army threatening it, are the primary settings of Coriolanus.[150][151]

- Rome in modern-day Italy is the site of the home of Philario, where Posthumus encounters Iachimo and wagers upon Innogen's loyalty, and also the setting of a short scene between two senators and a tribune at the end of act 3, of Cymbeline.[152][153][154][155]

- Rome in modern-day Italy is the settling of the whole of the first three acts of Julius Caesar.[156][157][158]

- Rome in modern-day Italy, together with a forest outside it, and the camp of the Goths led by Lucius preparing to attack it, are the only settings of Titus Andronicus.[159][160][161]

- Rouen:

- See also "French Court" under more-specific settings below.

- Rouen in France is captured by Joan and the French, then recaptured by Talbot and the English, in Henry VI, Part 1, and is the site of the Duke of Burgundy's defection to the French side; and later is the scene of Joan's execution at the stake.[162][163][164]

- Roussillon in France, of which Bertram is the young Count, is a setting of several episodes in All's Well That Ends Well, including its beginning and ending.[165][166][133][167]

S

- Salisbury in England is the setting of the death of Buckingham in Richard III.[168][169][170]

- Sardis in present-day Turkey, at Brutus' camp and mainly in his tent, is the setting of most of Act 4 of Julius Caesar, including the conflict between Brutus and Cassius and the first appearance of Caesar's ghost.[171][172]

- Scotland:

- Shrewsbury in England, the camps of the opposing forces, and the battlefield, are the settings of the Battle of Shrewsbury, which comprises most of the action of the last two acts of Henry IV, Part 1.[176][177][178][179]

- Sicily:

- See also "Messina", and, under more-specific settings below, "Pompey's court".

- Sicilia in modern day Italy, but in the world of the play a kingdom of which Leontes is the king, is the setting of acts 1, 2, most of 3, and 5 of The Winter's Tale.[180][35][181]

- Southampton in England is the setting of Henry's departure for France, and of the exposure of the traitors Cambridge, Scroop and Grey, in Henry V.[182][183][184]

- St Albans in England is the setting of several scenes surrounding Cardinal Beaufort's opposition to the Lord Protector in Henry VI, Part 2, and later the play climaxes at the Battle of St Albans.[185][186][187][188]

- St Edmundsbury (i.e. Bury St Edmunds in England) is the setting of a battle between the forces of King John and the Dauphin in the final act of King John.[189][190]

T

- Tarsus in modern-day Turkey is the place where the child Marina is fostered to Cleon and Dionyza, and the location of the later plot to murder her, in Pericles.[191][11][192]

- Tewkesbury in England is the site of the Battle of Tewkesbury, which secured Edward's victory, and which is dramatized in Henry VI, Part 3.[193][194][195]

- Thebes in modern-day Greece, but in the play governed by the tyrant Creon, is the setting of our first encounter with Palamon and Arcite, the title characters of The Two Noble Kinsmen.[196][197]

- For Towton see "York".

- Troy:

- See also "Ilium" under more-specific settings below.

- Troy in modern-day Turkey, the camp of the Greek soldiers besieging it, and the battlefield outside it, are the settings of Troilus and Cressida.[198][199][200]

- For Tunis see "Sea" under less-specific settings, below.

- Tyre in modern-day Lebanon is the home of the title character of Pericles, Prince of Tyre and the setting of several scenes in the first act, before he embarks upon the journey which comprises most of the play's plot.[201][11][202]

U

V

- Venice:

- Verona:

- Verona in modern-day Italy is the main setting of Romeo and Juliet.[209][210]

- Verona in modern-day Italy is the home of Petruchio in The Taming of the Shrew, and the setting of most of the 4th act.[211][212]

- Verona in modern-day Italy is the original home of Julia, Valentine and Proteus in The Two Gentlemen of Verona and is the setting of most of the first two acts.[213][214][215][216]

- Vienna:

- Vienna in present-day Austria, although not literally a setting of Hamlet, is the setting of its play-within-a-play The Murder of Gonzago, also known as The Mousetrap.[217][124][218]

- Vienna in present-day Austria, but in the play a city state governed by a duke, is the only setting of Measure for Measure.[219][220][221]

W

- Wakefield in England is the site of the Battle of Wakefield, dramatized in Henry VI, Part 3, in which young Rutland, and later his father the Duke of York, are killed by Clifford and the Queen.[222][223]

- Wales:

- See also "Milford Haven" and, under more-specific settings below, "Flint Castle".

- Wales is the setting of two related scenes in Richard II. In the first, which is given no more specific location, the Earl of Salisbury is abandoned by the king's Welsh forces.[d] The related scene of King Richard's return from Ireland to discover he has no military support is, in the text, set near "Barkloughly Castle", which means Harlech Castle.[e][224][226][227]

- Wales, without being specified more accurately in the text, is the location of Glendower's court, where the rebels - Glendower, Mortimer, Worcester and Hotspur - meet to plan the division of the kingdom, in Henry IV, Part 1.[f][229][228]

- Windsor

- See also, under more-specific settings below, "The Garter Inn" and "Herne's Oak".

- Windsor in England and its environs are the only setting of The Merry Wives of Windsor.[230][231][232][233]

Y

- York:

- See also "Park" under less-specific settings below.

- York in England is the place where the Queen Margaret has had The Duke of York's head placed above the gates in Henry VI, Part 3.[234][235]

- Near York in England, and immediately following the scene mentioned above, are several battle scenes which dramatize the Battle of Towton, although Shakespeare does not mention Towton as a location, in Henry VI, Part 3.[236][237]

- York in England is the setting of a stand-off where Edward is, at first, barred the gates by the Mayor, and then of the alliance between Edward and Montgomery, in Henry VI, Part 3.[238][239]

Less-specific settings

- Battlefield:

- For specific battlefields, see the entry for the place after which the battle is named.

- An unnamed battlefield is the setting of a supernatural scene in which Joan communes with fiends, in Henry VI, Part 1, followed by her capture, and then Suffolk captures Margaret. Historically, Joan was captured at Compiègne in France, and Suffolk's capture of Margaret is unhistorical.[240][241]

- Castle:

- For specific castles identified by Shakespeare, see more-specific settings below.

- A castle somewhere in England is the setting of the death of Arthur in King John. There is an internal scene in which Arthur persuades Hubert not to kill him, and an external scene in which Arthur dies in trying to escape, and his body is discovered. Shakespeare gives no indication which castle is intended: speculation has included Northampton, Dover, Canterbury or the Tower of London.[242] Historically, Arthur was not held in England at all, but at Rouen Castle in France.[243]

- In Henry IV, several scenes (act 2 scene 3 of Part 1, and act 1 scene 1 and act 2 scene 3 of Part 2) are set at the castles which are the homes of Hotspur and Northumberland, without the location being specified other than being described by Rumour as "this worm-eaten hole of ragged stone".[244] Historically in both cases this would have been Warkworth Castle.[245][246]

- In Henry VI, Part 3, a scene is set at "your Castle",[247] near Wakefield: meaning York's. Historically, that was Sandal Castle.[248]

- Forest:

- Where a setting is a named forest which exists in the real world, it is listed instead under more-specific settings below.

- A forest outside Athens is the primary location of the middle three acts of A Midsummer Night's Dream.[249]

- A forest outside Athens - featuring the mouth of a cave in which Timon is dwelling - is the setting of much of the last two acts of Timon of Athens.[250]

- A forest outside Athens is the setting of the middle act of The Two Noble Kinsmen.[251][252][253]

- A forest outside Milan is the home of the outlaws of whom Valentine becomes the leader in The Two Gentlemen of Verona, and is the setting of the play's climax.[254][255]

- A forest near Rome is the setting of the second act of Titus Andronicus, comprising the murder of Bassianus and the framing of Titus' sons for it, and of the rape and mutilation of Lavinia.[256]

- Gaol:

- An unspecified gaol is the setting of the (unhistorical) meeting of York with Mortimer in Henry VI, Part 1.[257]

- Graveyard:

- Island:

- An unnamed remote island is the setting of the whole of The Tempest except for the opening storm scene at sea.[262][263][264]

- Park:

- A park, where Edward is out hunting accompanied by his captors, is the setting of the rescue of Edward by Richard and his followers, in Henry VI, Part 3. The only textual hint to its location is that Edward is the prisoner of the Bishop of York. Historically, Edward was held at Middleham Castle, in Yorkshire.[265][266][267][268]

- Road:

- The road from Verona to Padua is the setting of the "How bright and goodly shines the moon!"[269] scene of The Taming of the Shrew.[270]

- The road to the Tower of London is the setting of the final parting of Queen Isabel and King Richard, in Richard II.[271][272]

- The road to Westminster Abbey, for the coronation of Henry V, is the setting of the climax - with the final rejection of Falstaff - of Henry IV, Part 2.[273]

- On a march sometime after the Battle of Wakefield the three sons of York witness the vision of the three suns in the sky, learn the details of their father's death, and meet Warwick who gives them the bad news of the outcome of the second battle of St Albans, in Henry VI, Part 3.[g][274]

- A street in London is the setting of several scenes in Henry VIII, in which some gentlemen meet to discuss the affairs of the day, and in one case to witness the coronation procession of Anne Bullen.[275]

- Ship:

More-specific settings

Locations identified as being in or around the home of a specific character are not listed, including where that home is a "castle", "cave" or "cell". Similarly, the "court" of any character who is a ruler is not listed unless Shakespeare gives it a specific location. Also not listed are generic locations such as "abbey", "brothel", "mart", "palace", "prison", "seashore" or "street", nor buildings given fictional names such as "the Porpentine", "the Phoenix" and others in The Comedy of Errors or "the Elephant" in Twelfth Night.

Military camps are not listed separately, and where relevant are mentioned under the name of the city being besieged or the place after which the battle is named.

Many Shakespearean characters are named after places: usually because they are known by their noble title rather than their actual name. This list does not assume that the homes of those characters are in that place unless Shakespeare's text explicitly places them there: even where that was true of the historical person upon whom the character is based. For example, there is no listing on this page for Gloucester in England (although see "Gloucestershire" below) even though there are characters usually described as Gloucester in King Lear, Henry IV (Part 2), Henry V, all three parts of Henry VI, and Richard III, and some scenes are set at their homes.

- Agincourt (i.e. Azincourt in France) the site of the Battle of Agincourt, and the camps of the French and English soldiers, are the settings of the main episode of Henry V including Henry's decisive victory.[278][279]

- For Arden or Ardennes see "Forest of Arden".

- Auvergne in France is the setting of the Countess of Auvergne's attempt to entrap Talbot, in Henry VI, Part 1.[280][281]

- For Barkloughly Castle in Richard II, see "Wales" under nations, cities and towns above.

- Baynard's Castle, then in London, England (not to be confused with Barnard Castle) is the setting of the Lord Mayor and citizens' plea to Richard to become king, in Richard III.[282][283]

- Berkeley Castle is the destination of a scene in which the Duke of York encounters Bolingbroke and his supporters, in Richard II.[284][285]

- Birnam Wood in Scotland is the rendezvous of the Scottish and English forces opposing Macbeth, in Macbeth. In a short scene set there, Malcolm fulfils the witches' prophecy that "Macbeth shall never vanquished be until great Birnam Wood to high Dunsinane Hill shall come against him"[286] by ordering his soldiers to each cut down a bough from the forest and carry it before them.[287][288][289]

- Blackfriars in London, England, is the setting of the trial of Queen Katherine in Henry VIII, and of the subsequent scene (historically at the adjoining Bridewell Palace) in which Katherine and her women commune with Wolsey and Campeius.[290][291]

- For Boar's Head see "Eastcheap".

- Bristol Castle is the scene of the condemnation and deaths of Bushy and Green in Richard II.[292][293]

- Capitol:

- Peter Holland, referring to Shakespeare's plays set in Ancient Rome, says: "Shakespeare appears to have assumed that the Capitol was the seat of the Senate but it was properly, to be pedantic, the temple of Jupiter on the Capitoline Hill while the Senate met near the Forum."[294][295]

- The Capitol in Rome in present-day Italy is where Coriolanus stands for the role of Consul, in Coriolanus.[296][294]

- The Capitol in Rome in present-day Italy is the setting of the murder of Caesar in Julius Caesar.[297][298][299]

- Cleopatra's Monument in Alexandria, Egypt, is the setting of the climax of Antony and Cleopatra, including the deaths of both title characters.[300][301][302][303]

- Diana's Temple at Ephesus is the scene of the climax of Pericles, the reconciliation of Pericles and Thaisa.[304][305]

- Dunsinane Hill in Scotland is fortified by Macbeth, and is the site of his final battle and death, in Macbeth.[306][307]

- Eastcheap in London, England, is the location of a tavern frequented by Falstaff, Hal and their companions in Henry IV part 1 and part 2. It is often labelled the "The Boar's Head" after a real inn in Eastcheap, although that name is never used by Shakespeare.[308][309][310][311] The context suggests that the scenes surrounding Falstaff's death in Henry V happen in the same location.[312][313]

- Ely House in Holborn, London, England, is the setting of John of Gaunt's "This sceptred isle"[314] speech, and his death, in Richard II.[315][316][317]

- English Court. Many scenes in the English history plays are set at the English court, without the king's palace being named. The main seats of the court in Shakespeare's time (Greenwich, Hampton Court and Whitehall) had not been built at the time of the Wars of the Roses, so in most cases the court, historically, would have met at the Tower of London, although Richmond was favoured by Richard II. Windsor was a day's journey from London, and several events dramatized by Shakespeare happened at Westminster.[318][319][320][q]

- Flint Castle in Wales is the setting of Richard's surrender to Bolingbroke in Richard II.[341][342][343]

- The Forest of Arden is the setting of the whole play As You Like It, other than the court scenes and those set at Oliver's house. Since the play is set in France it may represent the Ardennes Forest, or equally for its original audiences, the Forest of Arden in Warwickshire, England, Shakespeare's home county.[344][94][95]

- French Court: Similarly to the English court, Shakespeare sometimes places scenes in the French court, without giving its location.[t]

- Gad's Hill, now part of Higham, near Rochester, in Kent, England, is the setting of a robbery committed by Falstaff and his followers, and then of another robbery committed upon them by Poins and Hal, in Henry IV, Part 1.[348][349][350][351][352]

- The Garter Inn is the lodging of Sir John Falstaff, and as such the setting of many scenes in The Merry Wives of Windsor.[353][354]

- Gaultree Forest, England, is the setting of an episode separate from the main plot of Henry IV, Part 2 which takes up much of its fourth act. [355][356][357]

- Gloucestershire:

- Gloucestershire, a county in England, on the route to Berkeley Castle, is the setting of a scene between Bolingbroke and his supporters in Richard II.[358][285]

- Gloucestershire, a county in England, without any specific town or city being specified, is the home of Justice Shallow and the setting of several rural scenes in Henry IV, Part 2.[359][360]

- For Harlech Castle see "Wales" under nations, cities and towns above.

- Herne's Oak, a tree in Windsor Park, is the meeting place for the final humiliation of Falstaff, and the setting of the climax of The Merry Wives of Windsor.[361][362][363]

- Ilium, the royal palace of Troy, is the setting of most scenes set within Troy's walls in Troilus and Cressida: Ilium, Ilion or Ilyion are also alternative names for the city of Troy, named after its founder Ilus.[364]

- For Jerusalem Chamber see "Westminster Palace" below.

- Kenilworth Castle in England is where Henry learns of the defeat of Cade, and then of the threat from York, in Henry VI, Part 2.[365][366]

- Kimbolton Castle in England is the home of the divorced queen Katherine in Henry VIII.[367][368][369]

- For Kent see "London and Kent" under "London" above.

- Pomfret Castle:

- Pomfret Castle (i.e. Pontefract Castle in England) is the setting of the killing of King Richard by Piers of Exton in Richard II.[370][371][372]

- Pomfret Castle (i.e. Pontefract Castle in England) is the setting of the execution of Rivers, Grey and Vaughan in Richard III.[373][374]

- Pompey:

- Pompey's Court is a setting in Antony and Cleopatra. Its location (historically on Sicily in present-day Italy) is not specified in the text.[375][376]

- Pompey's Galley is the setting of the central "What manner o'thing is your crocodile?"[377] scene of Antony and Cleopatra.[378][379] The prior scene on land (act 2 scene 6) is not given a location in the text. In Shakespeare's sources it occurs "by the mount of Misena", which is in the vicinity of Naples in modern-day Italy.[380][381]

- For Richmond Palace see "English Court".

- Southwark in London, England, is one of the locations of Jack Cade's rebellion in Henry VI, Part 2.[382][383] See also "London and Kent" under "London" above.

- Swinstead Abbey is an abbey in Lincolnshire, England, whose orchard is the setting of the death agonies of King John, supported by his Barons, in King John. In history, it is Swineshead Abbey that King John visited, and the confusion of Swinstead and Swineshead was common in the late-sixteenth century.[384][385]

- The Temple Garden in London, England, is the setting of the debate between York and Somerset in Henry VI, Part 1, in which the nobles each pluck a white or red rose, establishing their factions for the Wars of the Roses.[386][387][39]

- Tower of London:

- See also "English Court".

- See also "Road" under less-specific settings, above.

- The Tower of London is the setting of the conflict between Gloucester's men in blue coats, and Winchester's men in tawny coats, in Henry VI, Part 1.[388][389]

- The Tower of London is the setting of a short scene in which Lord Scales promises to send Matthew Gough to fight Jack Cade, in Henry VI, Part 2.[390][391]

- The Tower of London is the setting of two scenes in Henry VI, Part 3. In the first, Henry is freed from captivity to join his new allies, Warwick and Clarence.[392][393] In the other, the recaptured Henry is murdered in his cell by Richard.[394][395][170]

- The Tower of London is the setting of several scenes in Richard III including:

- A scene in which Clarence recounts his feverish dream, and then is murdered.[396][397]

- The setting of the divided councils at which Hastings is condemned to death, and its aftermath.[398][399]

- An external scene in which Elizabeth and the other women are refused access to the princes in the Tower.[400][401]

- For Westminster Abbey see "Westminster Palace", and, under less-specific settings above, "Road".

- Westminster Palace is the location of the court scenes of Henry IV, Part 2, including the final confrontation and reconciliation of Henry and Hal, and the king's death. Inconsistently, the Jerusalem Chamber (where the king collapses and later dies) is in fact in Westminster Abbey.[402][403]

- For Whitehall see "York Place".

- For Windsor Castle see "English Court".

- For Windsor Park see "Herne's Oak".

- York Place is renamed Whitehall during the course of the action of Henry VIII ("Sir, you must no more call it York Place ... 'tis now the King's, and called Whitehall.").[404] According to Shakespeare and Fletcher's source Holinshead, York Place was the venue of the feast dramatized in the first act, at which, unhistorically, the king first meets Anne Bullen.[405][368][406]

References

Notes

- ^ Throughout this page "Shakespeare" is used as a shorthand for "the author(s) of the play(s)" even though many plays listed are colloborations. See William Shakespeare's collaborations.

- ^ See Henry VI, Part 1 act 4 scenes 3 & 4.

- ^ Iden describes himself as "A poor esquire of Kent"[105]

- ^ Historically, according to Shakespeare's source Holinshed, these events occurred at Conwy.[224]

- ^ Historically, on returning from Ireland, Richard instead landed at Milford Haven.[225]

- ^ Shakepeare's source, Holinshed, places the meeting of Glendower and the other rebels at the home of the Archdeacon of Bangor.[228]

- ^ Historically, according to Shakespeare's source Hall, Edward and Warwick met at Chipping Norton.[274]

- ^ Historically the events depicted in this scene happened at Windsor Castle, where Mowbray was being held.[322][323]

- ^ Historically, the events depicted in the "deposition scene" of Richard II happened at Westminster Hall.[317][319]

- ^ Historically, the funeral of Henry V, which forms part of the action of the opening scene of Henry VI, Part 1, happened at Westminster Abbey, although the events recounted in the scene actually happened over a number of years.[328][329]

- ^ The opening scene of Henry VI, Part 3 is set at the English Parliament which met at Westminster Palace.[332]

- ^ According to Shakespeare's source, Hall, Edward and Elizabeth met at Grafton Manor.[333]

- ^ Queen Elizabeth took sanctuary at Westminster Abbey, although the text does not refer to it.[334][335]

- ^ In history, the "palace" referred to at 4.10.1 is that of the Bishop of London.[336]

- ^ In this case the scene numbers are taken from the Oxford Complete Works 2nd Edition (which is the source for all references to Shakespeare's works on this page). In Cox & Rasmussen 2001, act 4 scene 5 is scene 4, and scenes 9 & 10 are one scene numbered 8.

- ^ The events of the closing scene of Henry VIII, which dramatizes the christening of Elizabeth I, probably happened historically at Greenwich Palace[339]

- ^ Scenes which are not otherwise listed on this page, because they happen at the English court without Shakespeare's text specifying its location, include:

King John: Act 1 scene 1, act 4 scene 2 and act 5 scene 1;[321]

Richard II: Act 1 scenes 1[h] & 4, act 2 scene 2, act 4 scene 1,[i] and act 5 scenes 3, 4 & 6;[324][325]

Henry IV Part 1: Act 1 scene 1, act 1 scene 3, and act 3 scene 2;[326]

Henry V: Act 1 scenes 1 & 2;[327]

Henry VI Part 1: Act 1 scene 1,[j] act 3 scene 1, and act 5 scenes 1 & 4;[330]

Henry VI Part 2: Act 1 scenes 1 & 3, and act 4 scene 4;[331]

Henry VI Part 3: Act 1 scene 1,[k] act 3 scene 2,[l] act 4, scenes 1, 5,[m] 9 & 10,[n][o] and act 5 scene 7;[337][335]

Richard III: Act 1 scenes 1 & 3, act 2 scenes 1, 2 & 4, act 4 scenes 2, 3 & 4;[338]

Henry VIII: Act 1 scenes 1, 2 & 3, act 2 scenes 2 & 3, act 3 scene 2, and act 5 scenes 1, 2, 3 and 4.[p][340] - ^ Act 3 scene 5 contains the line "Prince Dauphin, you shall stay with us in Rouen."[345]

- ^ Historically the peace was settled at Troyes in France.[346]

- ^ Scenes which are not otherwise listed on this page, because they happen at the French court without Shakespeare's text specifying its location, include:

Henry V: Act 2 scene 4, act 3 scenes 4 & 5;[r] and act 5 scene 2;[346][s]

Henry VI Part 1: Act 1 scene 2;

Henry VI Part 3: Act 3 scene 3.[347]

Footnotes

References to works by Shakespeare are to The Oxford Shakespeare: The Complete Works Second Edition (i.e. Jowett, Montgomery, Taylor & Wells 2005). Under its numbering system Hamlet 3.1.58 means act 3, scene 1, line 58. In plays which it presents without act divisions, such as Pericles, 1.17 means scene 1 line 17. In the case of King Lear, which the Oxford Complete Works presents in two separate versions, references are to "The Tragedy of King Lear" (the folio version) at pp.1153-1184. In Henry V, 0 in place of a scene number means the chorus to that act. "SD" references a stage direction. An "n" after a page number indicates a note on that page rather than its body text.

- ^ Antony and Cleopatra 3.7.50-52.

- ^ Wilders 1995, pp. 193n, 199n, 200n.

- ^ Bevington 2005, pp. 179n, 184n, 185n.

- ^ Antony and Cleopatra 3.13.171-172.

- ^ Wilders 1995, pp. 90n, 95n, 106n, 119n, 146n, 179n, 185n, 208n, 211n, 225n, 226n, 230n, 232n, 235n, 237n, 240n, 241n, 245n, 247n, 248n, 252n, 54n, 263n, 270n, 275n.

- ^ Bevington 2005, p. 188n.

- ^ King John 2.1.1.

- ^ Honigmann 1954, pp. 21SD, 54SD, 59SD, 74SD, 79SD.

- ^ Lander & Tobin 2018, pp. 8–9, 164SD, 164n, 208n.

- ^ Pericles 1.17-19.

- ^ a b c d Whitfield 2015, p. 22.

- ^ Gossett 2004, p. 171n.

- ^ Coriolanus 4.4.1-2.

- ^ Holland 2013, pp. 328n, 330n, 399n.

- ^ Antony and Cleopatra 3.1.34-35.

- ^ Antony and Cleopatra 3.6.64.

- ^ Wilders 1995, p. 182n.

- ^ Bevington 2005, p. 170n.

- ^ A Midsummer Night's Dream 1.1.11-12.

- ^ A Midsummer Night's Dream 1.1.160-163.

- ^ Bartels 2003, p. 152.

- ^ Whitfield 2015, pp. 30, 34.

- ^ Timon of Athens 2.2.17-18.

- ^ Whitfield 2015, p. 30.

- ^ Dawson & Minton 2008, pp. 159n, 264n, 271n.

- ^ The Two Noble Kinsmen 221-222.

- ^ Potter 1997, p. 139n.

- ^ Henry VI, Part 3 113-114.

- ^ Cox & Rasmussen 2001, p. 343n.

- ^ The Merchant of Venice 1.1.161.

- ^ The Merchant of Venice 3.4.84-85.

- ^ a b Bartels 2003, pp. 154–155.

- ^ Drakakis 2010, pp. 188n, 222n, 272n, 289n, 319n, 325n, 367n.

- ^ The Winter's Tale 3.3.1-2.

- ^ a b Whitfield 2015, pp. 94–96.

- ^ Pitcher 2010, pp. 100–102, 235n, 247n, 249n, 259n.

- ^ Henry VI, Part 1 4.2.1.

- ^ Burns 2000, pp. 232n–233n.

- ^ a b c Whitfield 2015, p. 169.

- ^ Richard III 5.3.1

- ^ Siemon 2009, pp. 379n, 381n, 411n, 412n.

- ^ Whitfield 2015, p. 174.

- ^ Cymbeline 3.1.12-14.

- ^ Wayne 2017, pp. 145n, 159n, 161n, 174n, 179n, 195n, 199n, 204n, 231n, 237n, 263n, 313n.

- ^ Whitfield 2015, p. 135.

- ^ King Lear 4.3.21.

- ^ a b Whitfield 2015, p. 133.

- ^ Coriolanus 1.2.27.

- ^ Coriolanus 115-117.

- ^ Holland 2013, pp. 145-146n, 174n, 185n, 193n, 196n, 202n, 205n, 212n.

- ^ Whitfield 2015, pp. 50–51.

- ^ Richard II 198-199.

- ^ Forker 2002, p. 207n.

- ^ Henry IV, Part 1 4.2.13.

- ^ Henry IV, Part 1 4.2.1.

- ^ Henry IV, Part 1 4.2.38-39.

- ^ Kastan 2002, p. 288n.

- ^ Henry VI, Part 3 4.10.32.

- ^ Cox & Rasmussen 2001, p. 333n-334n.

- ^ Othello 2.1.213.

- ^ a b Whitfield 2015, p. 56.

- ^ Thompson & Honigmann 2016, pp. 12, 21–22, 165n, 186n.

- ^ King Lear 3.6.48-50.

- ^ King Lear 4.1.54.

- ^ Foakes 1997, pp. 317n, 321n, 326n, 357n.

- ^ Hamlet 1.2.173.

- ^ Whitfield 2015, p. 119.

- ^ Berry 2016, pp. 1–2.

- ^ Thompson & Taylor 2006, pp. 147n, 227n, 366n, 409n.

- ^ The Taming of the Shrew Induction.2.16-17.

- ^ The Taming of the Shrew Induction.2.20

- ^ Hodgdon 2010, pp. 2, 139n, 150n.

- ^ Macbeth 4.3.44-45.

- ^ Muir 1984, p. 122.

- ^ Brooke 1990, p. 72.

- ^ Henry VI, Part 3 2.5.128.

- ^ Henry VI, Part 3 3.1.13-14.

- ^ Cox & Rasmussen 2001, p. 261n.

- ^ Henry VI, Part 3 4.2.0SD

- ^ Cox & Rasmussen 2001, pp. 305n, 307n.

- ^ The Comedy of Errors 1.1.28-30.

- ^ Berry 2016, pp. 41–42.

- ^ Cartwright 2017, pp. 49–51.

- ^ Pericles 5.1.227.

- ^ Gossett 2004, pp. 289n, 307n, 396n.

- ^ Macbeth 2.4.36-37.

- ^ Muir 1984, p. 117.

- ^ All's Well That Ends Well 3.2.68-69.

- ^ All's Well That Ends Well 5.3.125-128.

- ^ Whitfield 2015, p. 116.

- ^ Macbeth 1.3.37.

- ^ Muir 1984, pp. 22, 72, 80, 86.

- ^ As You Like It 1.1.133-134.

- ^ a b Oliver 1968, p. 11.

- ^ a b Whitfield 2015, pp. 113–114.

- ^ Henry V 3.0.22-24.

- ^ Craik 1995, p. 231n.

- ^ Taylor 1982, p. 146n.

- ^ Henry V 3.0.26-27.

- ^ Craik 1995, pp. 201n, 215n.

- ^ Twelfth Night 1.2.1.

- ^ Whitfield 2015, pp. 98–99.

- ^ Macbeth 1.4.41-42.

- ^ Muir 1984, pp. 26, 33, 36, 45, 51, 58.

- ^ Henry VI, Part 2 5.1.75.

- ^ Knowles 1999, pp. 283n, 296n, 311n, 317n, 318n, 335n.

- ^ Romeo and Juliet 3.3.166-168.

- ^ Romeo and Juliet 5.1.66-67.

- ^ Levenson 2000, p. 173n.

- ^ All's Well That Ends Well 4.4.8-10.

- ^ All's Well That Ends Well 4.5.80.

- ^ Gossett & Wilcox 2019, p. 290n.

- ^ Much Ado About Nothing 1.1.1-2.

- ^ Whitfield 2015, p. 91.

- ^ The Two Gentlemen of Verona 2.5.1.

- ^ Whitfield 2015, p. 104-105.

- ^ Evans 1964, pp. 58, 67, 75, 77, 82, 95, 102, 107, 109, 116, 117.

- ^ Cymbeline 3.2.48-49.

- ^ Wayne 2017, pp. 243n, 250n, 272n, 280n, 282n, 316n, 319n, 322n, 324n, 332n, 347n.

- ^ Pericles 18.44-45.

- ^ Whitfield 2015, pp. 22, 23.

- ^ Gossett 2004, pp. 129, 323n, 346n.

- ^ Love's Labour's Lost 2.1.90.

- ^ a b Whitfield 2015, p. 109.

- ^ Kerrigan & Walton 2005, p. xxiv.

- ^ Henry VI, Part 1 1.5.1

- ^ Burns 2000, pp. 13, 149n, 162n–163n, 168n–169n.

- ^ The Taming of the Shrew 1.1.1-3.

- ^ The Taming of the Shrew 1.2.74.

- ^ Whitfield 2015, p. 103.

- ^ Hodgdon 2010, p. 159n.

- ^ All's Well That Ends Well 1.2.22.

- ^ a b Whitfield 2015, p. 115.

- ^ Henry VI, Part 1 4.1.3.

- ^ Burns 2000, p. 222n.

- ^ Antony and Cleopatra 3.1.6-7.

- ^ Wilders 1995, p. 171n.

- ^ Bevington 2005, p. 162n.

- ^ Pericles 5.138-141.

- ^ Whitfield 2015, pp. 22–23.

- ^ Gossett 2004, pp. 129, 222n.

- ^ Julius Caesar 4.2.334-337.

- ^ Julius Caesar 5.1.5-6.

- ^ Daniell 1998, pp. 155n, 298n, 306n, 307n, 314n, 316n.

- ^ Whitfield 2015, p. 50.

- ^ Henry IV, Part 1 127-128.

- ^ Kastan 2002, p. 183n.

- ^ Antony and Cleopatra 1.2.173-175.

- ^ Wilders 1995, pp. 113n, 128n, 142n, 145n, 174n, 186n.

- ^ Coriolanus 2.1.42-44.

- ^ Holland 2013, pp. 149n, 177n, 215n, 236n, 267n, 295n, 307n, 318n, 348n, 360n, 364n, 377n, 394n.

- ^ Cymbeline 1.1.98-99.

- ^ Cymbeline 3.7.0.SD.

- ^ Wayne 2017, pp. 164n, 215n, 279n.

- ^ Pitcher 2005, pp. 174n–175n.

- ^ Julius Caesar 1.2.157-158.

- ^ Julius Caesar 3.2.74.

- ^ Daniell 1998, p. 155n.

- ^ Titus Andronicus 1.1.70.

- ^ Whitfield 2015, p. 45.

- ^ Bate 2018, pp. 231n, 167n, 284n.

- ^ Henry VI, Part 1 3.2.1.

- ^ Burns 2000, p. 205n.

- ^ Norwich 1999, p. 225-226.

- ^ All's Well That Ends Well 1.2.18-19.

- ^ All's Well That Ends Well 5.1.29-30.

- ^ Gossett & Wilcox 2019, pp. 123n, 301n.

- ^ Richard III 4.4.468-469.

- ^ Siemon 2009, p. 377n.

- ^ a b Whitfield 2015, p. 173.

- ^ Julius Caesar 4.2.28.

- ^ Daniell 1998, pp. 155n, 274n, 277n.

- ^ Macbeth 1.2.28.

- ^ Muir 1984, p. 2.

- ^ Whitfield 2015, pp. 137–141.

- ^ Henry IV, Part 1 4.4.10-13.

- ^ Henry IV, Part 2 1.1.11-12.

- ^ Kastan 2002, pp. 280n, 294n, 303n, 312n, 319n, 324n, 335n.

- ^ Whitfield 2015, pp. 162–163.

- ^ The Winter's Tale 4.4.508-513.

- ^ Pitcher 2010, pp. 99–100, 145n, 219n, 310n, 327n, 337n.

- ^ Henry V 2.0.34-35.

- ^ Craik 1995, p. 167n.

- ^ Taylor 1982, p. 130n.

- ^ Henry VI, Part 2 1.2.56-57.

- ^ Henry VI, Part 2 5.5.35.

- ^ Knowles 1999, pp. 195n, 231n, 255n, 281n, 355n, 362n.

- ^ Whitfield 2015, p. 170.

- ^ King John 5.4.16-18.

- ^ Honigmann 1954, pp. 123SD, 123n.

- ^ Pericles 4.21.

- ^ Gossett 2004, p. 208n.

- ^ Henry VI, Part 3 5.3.18-19.

- ^ Cox & Rasmussen 2001, pp. 348n, 352n.

- ^ Whitfield 2015, pp. 172–173.

- ^ The Two Noble Kinsmen 1.2.3-5.

- ^ Potter 1997, p. 158n.

- ^ Troilus and Cressida Prologue.1.

- ^ Whitfield 2015, p. 19.

- ^ Bevington 2015, p. 359n.

- ^ Pericles 3.1.

- ^ Gossett 2004, pp. 194n, 204n.

- ^ The Merchant of Venice 1.1.114-115.

- ^ Whitfield 2015, pp. 59–62.

- ^ Drakakis 2010, pp. 169n, 201n, 227n, 244n, 246n, 250n, 255n, 268n, 280n, 316n, 331n.

- ^ Othello 1.1.107.

- ^ Berry 2016, pp. 51, 55–57.

- ^ Thompson & Honigmann 2016, pp. 119n, 132n, 139n.

- ^ Romeo and Juliet Prologue.2

- ^ Levenson 2000, p. 141n.

- ^ The Taming of the Shrew 1.2.1-2.

- ^ Whitfield 2015, p. 101.

- ^ The Two Gentlemen of Verona Title.

- ^ Whitfield 2015, pp. 104–105.

- ^ Evans 1964, pp. 43, 49, 54, 64, 65, 79.

- ^ Sanders & Jackson 2005, p. xxxiv.

- ^ Hamlet 3.2.226-227.

- ^ Thompson & Taylor 2006, pp. 313n, 314.

- ^ Measure for Measure 1.1.44-45.

- ^ Braunmuller & Watson 2020, p. 122.

- ^ Whitfield 2015, p. 107.

- ^ Henry VI, Part 3 2.1.107-108.

- ^ Cox & Rasmussen 2001, pp. 208n, 211n.

- ^ a b Forker 2002, p. 306n.

- ^ Forker 2002, p. 315n.

- ^ Richard II 3.2.1.

- ^ Forker 2002, p. 314n-315n.

- ^ a b Kastan 2002, p. 239n.

- ^ Henry IV, Part 1 4.3.95-98.

- ^ The Merry Wives of Windsor 2.1.61-62.

- ^ The Merry Wives of Windsor 2.2.96-99.

- ^ Berry 2016, pp. 68, 69.

- ^ Melchiori 2000, pp. 9–10, 124n.

- ^ Henry VI, Part 3 2.2.1.

- ^ Cox & Rasmussen 2001, p. 232n.

- ^ Cox & Rasmussen 2001, pp. 232n, 243n, 246n, 247n, 254n.

- ^ Whitfield 2015, p. 171.

- ^ Henry VI, Part 3 4.8.7-8.

- ^ Cox & Rasmussen 2001, p. 323n.

- ^ Burns 2000, pp. 23–24, 262n.

- ^ Norwich 1999, p. 225.

- ^ Honigmann 1954, pp. 89SD, 89n, 109SD.

- ^ Lander & Tobin 2018, p. 13.

- ^ Henry IV, Part 2 Induction.35.

- ^ Kastan 2002, p. 198n.

- ^ Bulman 2016, pp. 165n, 243n.

- ^ Henry VI, Part 3 1.2.50.

- ^ Cox & Rasmussen 2001, p. 203n.

- ^ A Midsummer Night's Dream 1.2.94-95.

- ^ Dawson & Minton 2008, pp. 271n, 310n, 320n, 331n.

- ^ The Two Noble Kinsmen 2.3.53.

- ^ The Two Noble Kinsmen 2.6.3-4.

- ^ Potter 1997, p. 4.

- ^ Evans 1964, pp. 99, 119, 120.

- ^ Sanders & Jackson 2005, pp. xxix–xxx.

- ^ Bate 2018, p. 209n.

- ^ Burns 2000, p. 110n, 187n.

- ^ Hamlet 5.1.180.

- ^ Hamlet 5.1.65-66.

- ^ Berry 2016, p. 2.

- ^ Thompson & Taylor 2006, p. 409n.

- ^ The Tempest 1.2.171-172.

- ^ The Tempest 1.2.333-334.

- ^ Vaughan & Vaughan 2011, p. 171n.

- ^ Henry VI, Part 3 4.5.11.

- ^ Henry VI, Part 3 4.6.2-3.

- ^ Cairncross 1964, p. 105SD.

- ^ Cox & Rasmussen 2001, p. 314n.

- ^ The Taming of the Shrew 4.6.2

- ^ Heilman 1986, p. 133.

- ^ Richard II 5.1.1-2.

- ^ Forker 2002, p. 415n.

- ^ Bulman 2016, p. 417n.

- ^ a b Cox & Rasmussen 2001, p. 221n.

- ^ McMullan 2000, pp. 266n, 362n.

- ^ Gossett 2004, pp. 218n, 271n, 276, 341n, 367n.

- ^ Vaughan & Vaughan 2011, pp. 165n, 171n.

- ^ Henry V 4.7.86-88.

- ^ Whitfield 2015, pp. 164–165.

- ^ Henry VI, Part 1 2.2.38-40.

- ^ Burns 2000, pp. 61–62.

- ^ Richard III 3.5.96-98.

- ^ Siemon 2009, p. 294n.

- ^ Richard II 2.3.1 & 2.3.159-160.

- ^ a b Forker 2002, p. 291n.

- ^ Macbeth 4.1.108-110.

- ^ Macbeth 5.2.5-6.

- ^ Macbeth 5.4.3.

- ^ Brooke 1990, p. 5.

- ^ Henry VIII 2.2.138-139.

- ^ McMullan 2000, pp. 298n, 316n.

- ^ Richard II 2.3.162-164.

- ^ Forker 2002, p. 309n.

- ^ a b Holland 2013, p. 236n.

- ^ Daniell 1998, p. 232n.

- ^ Coriolanus 2.1.265.

- ^ Julius Caesar 1.3.36-37.

- ^ Julius Caesar 3.1.11-12.

- ^ Daniell 1998, pp. 231n, 232n.

- ^ Antony and Cleopatra 4.14.3-4.

- ^ Antony and Cleopatra 4.14.6-7.

- ^ Wilders 1995, pp. 263n, 275n, .

- ^ Bevington 2005, pp. 237n, 248n.

- ^ Pericles 5.1.227.

- ^ Gossett 2004, p. 396n.

- ^ Macbeth 5.2.11-12.

- ^ Muir 1984, pp. 137, 144, 151.

- ^ Henry IV, Part 1 1.2.155.

- ^ Henry IV, Part 2 2.2.137-139.

- ^ Kastan 2002, pp. 205n, 267n.

- ^ Bulman 2016, pp. 220n, 183n, 213n, 248n, 413n.

- ^ Craik 1995, p. 156n.

- ^ Taylor 1982, p. 120n.

- ^ Richard II 2.1.40.

- ^ Richard II 1.4.56-57.

- ^ Richard II 2.1.216-217.

- ^ a b Whitfield 2015, p. 161.

- ^ Whitfield 2015, p. 151.

- ^ a b Forker 2002, p. 372n.

- ^ Bulman 2016, p. 358n.

- ^ Honigmann 1954, pp. 3SD, 96SD, 119SD.

- ^ Forker 2002, p. 179n.

- ^ Ure 1961, pp. 3n–4n.

- ^ Ure 1961, pp. 3SD, 3n–4n, 39SD, 69SD, 124SD, 124n–125n, 159SD, 167SD, 177SD.

- ^ Forker 2002, pp. 179n, 274n, 372n, 442n–443n, 476n.

- ^ Kastan 2002, pp. 140n, 163n, 257n.

- ^ Taylor 1982, p. 94n.

- ^ Burns 2000, p. 115n, 120n.

- ^ Norwich 1999, pp. 201–203.

- ^ Burns 2000, pp. 115n, 194n.

- ^ Knowles 1999, pp. 149n, 173n, 312n.

- ^ Cox & Rasmussen 2001, p. 185n.

- ^ Cox & Rasmussen 2001, p. 267n.

- ^ Cox & Rasmussen 2001, p. 312n.

- ^ a b Cairncross 1964, p. 103SD.

- ^ Cox & Rasmussen 2001, p. 329n.

- ^ Cox & Rasmussen 2001, p. 185n, 267n, 296n, 312n, 329n, 365n.

- ^ Siemon 2009, pp. 133n, 168n, 214n, 224n, 239n, 317n, 328n, 333n.

- ^ Whitfield 2015, p. 181.

- ^ McMullan 2000, pp. 212n, 231n, 248n, 279n, 289n, 329n, 388n, 402n, 419n, 427n.

- ^ Richard II 3.2.205.

- ^ Berry 2016, p. 36.

- ^ Forker 2002, p. 336n.

- ^ As You Like It 1.1.109-110.

- ^ Henry V 3.5.64.

- ^ a b Craik 1995, pp. 344n–345n.

- ^ Cox & Rasmussen 2001, p. 280n.

- ^ Henry IV, Part 1 1.2.123-126.

- ^ Henry VI, Part 2 1.2.149-150.

- ^ Kastan 2002, pp. 158n, 191n.

- ^ Whitfield 2015, p. 162.

- ^ Ackroyd 1990, pp. 824–825.

- ^ The Merry Wives of Windsor 1.3.1.

- ^ Melchiori 2000, p. 145n.

- ^ Henry IV Part 2 4.1.1-2.

- ^ Bulman 2016, pp. 102, 317SD.

- ^ Whitfield 2015, pp. 163–164.

- ^ Richard II 2.3.1-3.

- ^ Henry IV, Part 2 4.2.124-125.

- ^ Bulmer 2016, pp. 79–91, 292n, 386n, 403n.

- ^ The Merry Wives of Windsor 4.4.27-30.

- ^ The Merry Wives of Windsor 4.6.19-20.

- ^ Melchiori 2000, pp. 273n, 275n.

- ^ Bevington 2015, pp. 155n, 161n.

- ^ Henry VI, Part 2 4.4.38.

- ^ Knowles 1999, p. 332n.

- ^ Henry VIII 4.1.34-35.

- ^ a b Whitfield 2015, p. 177.

- ^ McMullan 2000, p. 374n.

- ^ Richard II 5.1.51-52.

- ^ Richard II 5.4.8-10.

- ^ Forker 2002, p. 460n.

- ^ Richard III 3.3.8.

- ^ Siemon 2009, p. 270n.

- ^ Wilders 1995, p. 124n.

- ^ Bevington 2005, p. 120n.

- '^ Antony and Cleopatra 2.7.40.

- ^ Antony and Cleopatra 2.6.82.

- ^ Wilders 1995, p. 162n.

- ^ Wilders 1995, p. 154n.

- ^ Bevington 2005, p. 147n.

- ^ Henry VI, Part 2 4.4.26.

- ^ Knowles 1999, p. 328n.

- ^ King John 5.3.8.

- ^ Lander & Tobin 2018, p. 313n.

- ^ Henry VI, Part 1 2.4.3-4.

- ^ Burns 2000, p. 178n.

- ^ Henry VI, Part 1 1.4.1.

- ^ Burns 2000, p. 141n.

- ^ Henry VI, Part 2 4.5.4-6.

- ^ Knowles 1999, p. 316n.

- ^ Henry VI, Part 3 3.2.118-120.

- ^ Cox & Rasmussen 2001, pp. 316n–317n.

- ^ Henry VI, Part 3 5.5.82-84.

- ^ Cox & Rasmussen 2001, p. 359n.

- ^ Richard III 1.4.8-9.

- ^ Siemon 2009, p. 193n.

- ^ Richard III 3.2.28-29.

- ^ Siemon 2009, p. 272n, 280n.

- ^ Richard III 4.1.3.

- ^ Siemon 2009, p. 308n.

- ^ Henry IV, Part 2 2.4.358.

- ^ Bulman 2016, pp. 283n, 358n, 392n.

- ^ Henry VIII 4.1.96-99.

- ^ Berry 2016, pp. 63–64.

- ^ McMullan 2000, p. 256n.

Bibliography

- Ackroyd, Peter (1990). Dickens. Minerva (an imprint of Octopus Publishing Group). ISBN 0 7493 0647 5.

- Bartels, Emily C. "Shakepeare's View of the World". In Wells & Orlin (2003), pp. 151-164.

- Bate, Jonathan (2018). Titus Andronicus - Revised Edition. The Arden Shakespeare Third Series. Bloomsbury Publishing Plc. ISBN 978-135003-091-6.

- Berry, Ralph (2016). Shakespeare's Settings and a Sense of Place. University of Wales Press. ISBN 978-1-78316-808-8.

- Bevington, David (2015). Troilus and Cressida - Revised Edition. The Arden Shakespeare Third Series. Bloomsbury Publishing Plc. ISBN 978-1-4725-8474-8.

- Bevington, David (2005). Antony and Cleopatra - Updated Edition. The New Cambridge Shakespeare. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-61287-6.

- Braunmuller, A.R.; Watson, Robert N. (2020). Measure for Measure. The Arden Shakespeare Third Series. Bloomsbury Publishing Plc. ISBN 978-1-9042-7143-7.

- Brooke, Nicholas (1990). Macbeth. The Oxford Shakespeare. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-953583-5.

- Bulman, James C. (2016). King Henry IV Part 2. The Arden Shakespeare Third Series. Bloomsbury Publishing Plc. ISBN 978-1-9042-7137-6.

- Burns, Edward (2000). King Henry VI Part 1. The Arden Shakespeare Third Series. Thompson Learning. ISBN 0-17-4434936.

- Cairncross, Andrew S. (1964). King Henry VI Part 3. The Arden Shakespeare - Second Series. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-02711-X.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - Cartwright, Kent (2017). The Comedy of Errors. The Arden Shakespeare Third Series. Bloomsbury Publishing Plc. ISBN 978-1-9042-7124-6.

- Cox, John D.; Rasmussen, Eric (2001). King Henry VI Part 3. The Arden Shakespeare Third Series. Bloomsbury Publishing Plc. ISBN 1-903436-31-1.

- Craik, T. W. (1995). King Henry V. The Arden Shakespeare Third Series. Routledge. ISBN 0-17-443480-4.

- Daniell, David (1998). Julius Caesar. The Arden Shakespeare Third Series. Bloomsbury Publishing Plc. ISBN 978-1-9034-3621-9.

- Dawson, Anthony B.; Minton, Gretchen E. (2008). Timon of Athens. The Arden Shakespeare Third Series. Bloomsbury Publishing Plc. ISBN 978-1-9034-3697-4.

- Drakakis, John (2010). The Merchant of Venice. The Arden Shakespeare Third Series. Bloomsbury Publishing Plc. ISBN 978-1-9034-3681-3.

- Evans, Bertrand (1964). The Two Gentlemen of Verona. Signet Classics. Signet.

- Foakes, R. A. (1997). King Lear. The Arden Shakespeare Third Series. Bloomsbury Publishing Plc. ISBN 978-1-9034-3659-2.

- Forker, Charles R. (2002). King Richard II. The Arden Shakespeare Third Series. Bloomsbury Publishing Plc. ISBN 1-903436-33-8.

- Gossett, Suzanne (2004). Pericles. The Arden Shakespeare Third Series. Bloomsbury Publishing Plc. ISBN 978-1-9034-3685-1.

- Gossett, Suzanne; Wilcox, Helen (2019). All's Well That Ends Well. The Arden Shakespeare Third Series. Bloomsbury Publishing Plc. ISBN 978-1-9042-7120-8.

- Heilman, Robert B. (1986). The Taming of the Shrew - New Revised Edition. Signet Classics. Signet.

- Hodgdon, Barbara (2010). The Taming of the Shrew. The Arden Shakespeare Third Series. Bloomsbury Publishing Plc. ISBN 978-1-9034-3693-6.

- Holland, Peter (2013). Coriolanus. The Arden Shakespeare Third Series. Bloomsbury Publishing Plc. ISBN 978-1-9042-7128-4.

- Honigmann, E. A. J. (1954). King John. The Arden Shakespeare - Second Series. Thompson Learning. ISBN 978-1-903436-09-7.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - Jowett, John; Montgomery, William; Taylor, Gary; Wells, Stanley (2005). The Oxford Shakespeare: The Complete Works. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-926718-7.

- Kastan, David Scott (2002). King Henry IV Part 1. The Arden Shakespeare Third Series. Thompson Learning. ISBN 1-904271-35-9.

- Kerrigan, John; Walton, Nicholas (2005). Love's Labour's Lost. Penguin Shakespeare. Penguin Books.

- Knowles, Ronald (1999). King Henry VI Part II. The Arden Shakespeare Third Series. Thomas Nelson and Sons Ltd. ISBN 0-17-443494-4.

- Lander, Jesse M.; Tobin, J. J. M. (2018). King John. The Arden Shakespeare Third Series. Bloomsbury Publishing Plc. ISBN 978-19042-7139-0.

- Levenson, Jill L. (2000). Romeo and Juliet. The Oxford Shakespeare. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199535897.

- McMullan, Gordon (2000). King Henry VIII. The Arden Shakespeare Third Series. Thomson Learning. ISBN 978-1-903436-25-7.

- Melchiori, Giorgio (2000). The Merry Wives of Windsor. The Arden Shakespeare Third Series. Bloomsbury Publishing Plc. ISBN 0-17-443528-2.

- Muir, Kenneth (1984). Macbeth. The Arden Shakespeare - Second Series - 1984 Reissue. Thompson Learning. ISBN 1-903436-48-6.

- Norwich, John Julius (1999). Shakespeare's Kings. Penguin Books.

- Oliver, H. J. (1968). As You Like It. The New Penguin Shakespeare. Penguin Books.

- Pitcher, John (2005). Cymbeline. Penguin Shakespeare. Penguin Books.

- Pitcher, John (2010). The Winter's Tale. The Arden Shakespeare Third Series. Bloomsbury Publishing Plc. ISBN 978-1-9034-3635-6.

- Potter, Lois (1997). The Two Noble Kinsmen. The Arden Shakespeare Third Series. Bloomsbury Publishing Plc. ISBN 1-904271-18-9.

- Sanders, Norman; Jackson, Russell (2005). The Two Gentlemen of Verona. Penguin Shakespeare. Penguin Books.

- Siemon, James R. (2009). King Richard III. The Arden Shakespeare Third Series. Bloomsbury Publishing Plc. ISBN 978-1-9034-3689-9.

- Taylor, Gary (1982). Henry V. The Oxford Shakespeare. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-953651-1.

- Thompson, Ann; Taylor, Neil (2006). Hamlet. The Arden Shakespeare Third Series. Bloomsbury Publishing Plc. ISBN 978-1-904271-33-8.

- Thompson, Ayanna; Honigmann, E. A. J. (2016). Othello - Revised Edition. The Arden Shakespeare Third Series. Bloomsbury Publishing Plc. ISBN 978-1-4725-7176-2.

- Ure, Peter (1961). King Richard II. The Arden Shakespeare - Second Series (5th ed.). Routledge. ISBN 0-415-00882-4.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - Vaughan, Virginia Mason; Vaughan, Alden T. (2011). The Tempest - Revised Edition. The Arden Shakespeare Third Series. Bloomsbury Publishing Plc. ISBN 978-1-4081-3347-7.

- Wayne, Valerie (2017). Cymbeline. The Arden Shakespeare Third Series. Bloomsbury Publishing Plc. ISBN 978-1-9042-7130-7.

- Wilders, John (1995). Antony and Cleopatra. The Arden Shakespeare Third Series. Bloomsbury Publishing Plc. ISBN 978-1-904271-01-7.

- Wells, Stanley; Orlin, Lena Cowen, eds. (2003). Shakespeare: An Oxford Guide. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-924522-3.

- Whitfield, Peter (2015). Mapping Shakespeare's World. The Bodleian Library. ISBN 978-1-85124-257-3.

.png)