Liechtenstein artillery system

| Liechtenstein artillery system | |

|---|---|

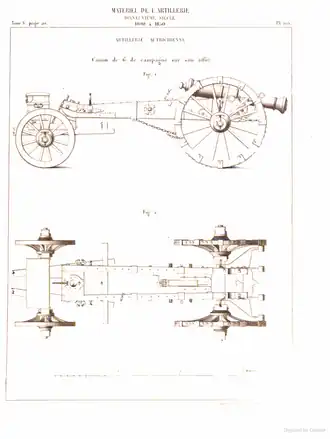

The new 6-pounder cannon was introduced as part of the Liechtenstein artillery system. | |

| Type | Artillery |

| Place of origin | |

| Service history | |

| Used by | |

| Wars | Seven Years' War French Revolutionary Wars Napoleonic Wars |

| Production history | |

| Designer | Joseph Wenzel I, Prince of Liechtenstein |

| Designed | 1753 |

The Liechtenstein artillery system of 1753 was a new system of artillery and organization introduced by Joseph Wenzel I, Prince of Liechtenstein and adopted by the Habsburg monarchy in the mid-18th century. The Austrian artillery performed poorly in the War of the Austrian Succession because it had become obsolete. Liechtenstein standardized the calibers of the field artillery to small, medium, and large caliber cannons, plus light and medium howitzers. Siege artillery was restricted to three increasingly heavy calibers. Mortars were limited to four calibers. In addition, the old guild system was abolished, the gunners were better-organized and trained, and gun carriages used interchangeable parts. The new system proved successful in the subsequent Seven Years' War. The Austrians continued to use the system as late as the French Revolutionary Wars and Napoleonic Wars of 1792–1815.

Background

Prince Wenzel Liechtenstein was appointed Director General of the Austrian artillery in 1744. In fact, Liechtenstein was the inhaber (proprietor) of a dragoon regiment and not an artilleryman. As early as 1743, Liechtenstein produced a 3-pounder cannon, but it proved to be a failure on the battlefield. In the War of the Austrian Succession, the obsolete Austrian artillery was consistently outclassed by the Prussian artillery. The problem with Austrian gunners of the 1740s was that they really belonged to a civilian guild. Austria only had 800 gunners during the War of the Austrian Succession. The gunners were assisted by the Handlanger, who were infantrymen assigned to gun crews in order to perform simple jobs like moving the gun.[1]

This was one of the most fruitful periods in the development of field artillery.[2] In 1731, Christian Nicolaus von Linger redesigned the Prussian artillery so that there were only four calibers, 3-, 6-, 12-, and 24-pounders.[3] The Prussian artillery introduced the screw quoin which was a wedge that elevated the gun barrel. Formerly, a simple wedge was used, but by adding a screw the gun crew was able to more easily adjust the gun tube's elevation.[4] In 1732, Florent-Jean de Vallière also reformed the French artillery by reducing calibers to 4-pounder, 8-pounder, 12-pounder, 16-pounder, and 24-pounder cannons.[5]

Reforms

Liechtenstein devoted a substantial amount of his family's wealth to the reform of Austria's artillery arm. Not only were the weapons upgraded, but also the gunners and the organization. A new artillery school was established at Budweis and Liechtenstein began conducting weapons tests. The screw quoin was copied from Prussia and carriage parts were made interchangeable.[6] The artillery pieces were made lighter in weight and had less ornamentation than the older cannons. Rammers and handspikes were attached to the gun carriage for the convenience of the gunners.[7]

The new field artillery was standardized to 3-pounder, 6-pounder, and 12-pounder field guns, plus 1-pounder and 7-pounder howitzers. Heavy artillery was made up of 12-pounder, 18-pounder, and 24-pounder siege guns. Mortars consisted of 10-, 30-, 60-, and 100-pounders. There was also a 100-pounder stone throwing mortar.[8] A field gun or cannon fired round shot or canister shot in a relatively flat trajectory.[9] A round shot was a cast iron ball that was most commonly used artillery ammunition.[10] Canister was a container filled with cast iron balls that turned a cannon into a monstrous shotgun, firing anti-personnel ammunition.[11] A howitzer fired at a higher angle than a cannon. Howitzers could fire canister shot or common shell and were mounted on carriages similar to cannons.[12] Mortars were mostly used in siege operations and fired large caliber common shells at a high angle.[13]

Austrian artillery officers and senior non-commissioned officers were trained at special schools. Only men who were Austrian subjects, healthy, literate, and unmarried were admitted to the service as enlisted gunners.[14] Liechtenstein's main assistants were Andreas Franz Feuerstein (1697–1774)[15] and Ignaz Walther von Waldenau (1713–1760).[16] The new organization included a Field Artillery Staff of 98–101 officers, the Netherlands national artillery corps of 8 companies, the Artillery Fusilier Regiment (3 battalions) which replaced the outmoded Handlanger, the Feldzeugamt or Ordnance Branch with 351 artificiers, and the Field Artillery Corps of three brigades of 8 companies each. Company strength was 95, but this was later increased to 140 by 1762. The number of companies was later increased from 8 to 10.[17]

In 1752, a French artillery officer, Jean-Baptiste Vaquette de Gribeauval was ordered on an inspection tour of the Prussian artillery that had proved so successful in the War of the Austrian Succession. France and Austria were allies in the Seven Years' War. In 1757, at the request of Empress Maria Theresa, Gribeauval was lent to the Austrian artillery arm because it had a shortage of high-ranking officers. The Frenchman distinguished himself as an artillery expert but also improved the Austrian engineer corps. Gribeauval was promoted Generalfeldwachtmeister for his efforts at the Siege of Neisse, but he really showed his talent in the Siege of Schweidnitz in 1762 where he led the Austrian artillery and engineers. The Prussian king Frederick the Great remarked that its prolonged defense was because of "that devil Gribeauval". After the war, the Frenchman returned to his own army and greatly improved its artillery by implementing the Gribeauval system.[18]

Characteristics

Caliber is normally measured as the inner diameter of the gun barrel. However, in the 1700s, caliber was often measured by the weight of a round shot. Charge weight is the amount of gunpowder needed to propel the shot or shell.[19][note 1]

| Nation | Caliber | Type | Charge weight | Gun tube weight |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Austria | 12-pounder | Cannon | 3 lb (1.4 kg) | 1,618 lb (734 kg) |

| Austria | 6-pounder | Cannon | 1+1⁄2 lb (0.7 kg) | 824 lb (374 kg) |

| Austria | 3-pounder | Cannon | 7⁄8 lb (0.4 kg) | 480 lb (218 kg) |

| Austria | 7-pounder | Howitzer | 1+1⁄4 lb (0.6 kg) | 563 lb (255 kg) |

| Prussia | 12-pounder | Cannon | 4 lb (1.8 kg) | 1,847 lb (838 kg) |

| Prussia | 6-pounder | Cannon | 2+1⁄4 lb (1.0 kg) | 935 lb (424 kg) |

| Prussia | 7-pounder | Howitzer | 2 lb (0.9 kg) | 572 lb (259 kg) |

History

The implementation of Liechtenstein's system made the Austrian artillery the best in Europe.[2] At the start of the Seven Years' War, the Prussians found to their dismay that their Austrian opponents had a very effective artillery arm that outclassed their own artillery in both accuracy and range.[22] During the Seven Years' War, Austria was able to put 768 artillery pieces into the field manned by 3,100 gunners.[2]

The newly proficient Austrian artillerists inflicted appalling losses on the Prussian infantry at the 1757 Battles of Prague and Kolin. Later in the year, the Prussians countered the Austrian guns by aggressively employing 12-pounders at the Battle of Leuthen.[23] At the Battle of Hochkirch on 14 October 1758, Austrian artillery concentrated "murderous" fire on the village at the center of the Prussian defenses. In particular, the Austrian howitzers inflicted serious losses on their foes.[24] In the Battle of Torgau on 3 November 1760, the Austrian army defended a ridge while supported by 275 guns. The attacking Prussians finally succeeded in forcing the Austrians to retreat, but only after suffering greater casualties than the defenders.[25]

The Austrians continued to use the Liechtenstein system as late as the French Revolutionary Wars of 1792–1801 and the Napoleonic Wars of 1804–1815.[26] As late as 1796, French General André Massena asserted that the Austrian artillery, "left nothing to be desired."[14] While the system proved to be the best in Europe in the 1750s, the Austrian gunners found themselves outmatched by the heavier guns of the French Gribeauval system during the later wars.[27]

Notes

- Footnotes

- ^ An English 3-pounder had a caliber of 2.91 in (74 mm), a 6-pounder 3.67 in (93 mm), and a 12-pounder 4.62 in (117 mm). Other nations' pounds and inches differed from the English measure. (Hazlett, Olmstead & Parks, p. 24)

- Citations

- ^ Kiley 2021, pp. 311–313.

- ^ a b c Kiley 2021, p. 311.

- ^ Duffy 1974, p. 112.

- ^ Kiley 2021, pp. 438–439.

- ^ Chartrand & Hutchins 2003, p. 4.

- ^ Kiley 2021, pp. 312.

- ^ Chartrand & Hutchins 2003, p. 5.

- ^ Kiley 2021, pp. 313.

- ^ Kiley 2021, p. 122.

- ^ Kiley 2021, p. 12.

- ^ Kiley 2021, p. 9.

- ^ Kiley 2021, p. 290.

- ^ Kiley 2021, p. 346.

- ^ a b Rothenberg 1980, p. 168.

- ^ Kiley 2021, p. 204.

- ^ Kiley 2021, p. 540.

- ^ Kiley 2021, pp. 312–313.

- ^ Kiley 2021, pp. 235–237.

- ^ Pivka 1979, p. 19–20.

- ^ Pivka 1979, pp. 20–24.

- ^ Kiley 2021, p. 580.

- ^ Duffy 1974, p. 113.

- ^ Duffy 1974, p. 118.

- ^ Duffy 1974, p. 185.

- ^ Duffy 1974, pp. 195–196.

- ^ Kiley 2021, p. 478.

- ^ Rothenberg 2007, p. 35.

References

- Chartrand, Rene; Hutchins, Ray (2003). Napoleon's Guns 1792-1815, vol. 1. Oxford, UK: Osprey Publishing Ltd. ISBN 1-84176-458-2.

- Duffy, Christopher (1974). The Army of Frederick the Great. New York, N.Y.: Hippocrene Books, Inc. ISBN 0-88254-277-X.

- Hazlett, James C.; Olmstead, Edwin; Parks, M. Hume (1983). Field Artillery Weapons of the American Civil War. Urbana, Ill.: University of Illinois Press. ISBN 0-252-07210-3.

- Kiley, Kevin F. (2021). Artillery of the Napoleonic Wars: A Concise Dictionary 1792-1815. Philadelphia: Pen and Sword Books Ltd. ISBN 978-1-84832-953-9.

- Pivka, Otto von (1979). Armies of the Napoleonic Era. New York, N.Y.: Taplinger Publishing. ISBN 0-8008-5471-3.

- Rothenberg, Gunther (1980). The Art of War in the Age of Napoleon. Bloomington, Ind.: Indiana University Press. ISBN 0-253-31076-8.

- Rothenberg, Gunther (2007). Napoleon's Great Adversary, The Archduke Charles and the Austrian Army, 1792-1814. Bloomington, Ind.: Indiana University Press. ISBN 0-253-33969-3.