Leptostomia

| Leptostomia Temporal range:

| |

|---|---|

| |

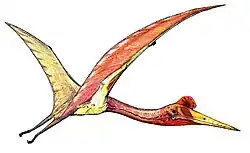

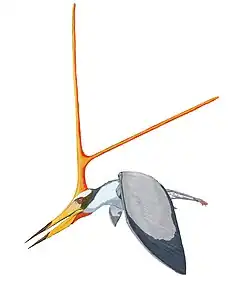

| Life restoration | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Order: | †Pterosauria |

| Suborder: | †Pterodactyloidea |

| Clade: | †Ornithocheiroidea |

| Clade: | †Azhdarchoidea |

| Genus: | † Smith et al., 2021 |

| Type species | |

| †Leptostomia begaaensis Smith et al., 2021

| |

Leptostomia is a genus of long-beaked pterosaur from the mid-Cretaceous (Cenomanian) of Morocco, North Africa. The type species is L. begaaensis, which was named and described in 2021 from sediments of the Kem Kem Group in Morocco.[1] It was a small animal with a long, slender bill which is thought to have been used to probe sediments for worms and other invertebrates, similar to kiwi birds and curlews. Leptostomia is likely a member of the Azhdarchoidea.

Discovery and naming

For decades, the fossiliferous outcrops of the Kem Kem Group in southern Morocco have produced pterosaur fossils. These rock layers belong to the upper Ifezouane Formation, dating to the Early Cretaceous period. The specific age however is uncertain, but it is believed to date back to the Cenomanian or perhaps Albian stages of the Cretaceous, about 112-94 million years ago. Leptostomia is known from two specimens, both of which were unearthed in the region and deposited at the Faculté des Sciences Aïn Chock; the holotype, an incomplete rostrum (FSAC-KK 5075), and the paratype, an incomplete dentary (FSAC-KK 5076). The preserved portion of the lower jaws may have lain in front of the holotype rostrum according to the authors' interpretation, with some overlap. The specimens of Leptostomia were examined by means of a CT scan.[1]

In 2021, paleontologists Roy E. Smith, David Michael Martill, Alexander Kao, Samir Zouhri and Nicholas R. Longrich described these remains as belonging to a new genus and species of pterosaur, named Leptostomia begaaensis. The generic name, Leptostomia, is a combination of the Ancient Greek words leptos (meaning "slim") and stoma (meaning "mouth"). The specific name begaaensis refers to the oasis village Hassi El Begaa where the holotype was found.[1]

Description

Leptostomia was a small, long-beaked pterosaur with adaptations for sediment probing. The holotype consists of two beak fragments. The fragments of Leptostomia were mostly flat, and had thick walls, unusual for a pterosaur. While many pterosaur beaks bear dorsal or ventral crests, Leptostomia lacks either. This gives it a straight, featureless beak. The holotype of Leptostomia measured 48 millimeters (1.9 in) in length, giving an estimated a total skull length measuring between 6 and 20 centimeters (2.4 and 7.9 in).[1]

The rostrum of Leptostomia is extremely thin, only 2.2 millimeters (0.087 in) deep at the front. The jaws are toothless, slightly upcurved, and taper anteriorly (frontly) toward the snout tip. The upper jaw had a narrow ridge, similar to that seen in many other pterosaurs, which would have occluded with a groove in the lower jaw. The median ridge on the occlusal (inside) surface of the rostrum extends across the length of the rostrum, however is more pronounced towards the posterior (back) end. Many small, slit-like foraminae can be found on the outside and occlusal surfaces of the mandible, similar to those of other azhdarchoids. As for the mandible, its ventral (bottom) margin is gently rounded; this is in contrast to the U-shaped or sharp margins present in Alanqa and Xericeps. Leptostomia is distinguished by other pterosaurs through a variety of traits, known as diagnostic traits. The lateral (side) and dorsal (top) rostral angles are less than or equal to 3 degress, a number much lower than that of pterosaurs like Alanqa. The cross-sections of the anterior rostrum and mandibular symphysis (the portion of the mandible where both halves meet) are semi-circular, in contrast to triangular or U-shaped cross-sections seen in contemporary pterosaurs. Notably, the beak of Leptostomia has thick cortices (bone walls) and a small central cavity (hollow space in the middle of the mandible). These cortices measure 2 millimetres (0.079 in) thick and surround the central cavity.[1]

Classification

Due to its fragmentary nature and unique anatomy, the affinities of Leptostomia are unclear; Smith and colleagues (2020) suggested that the genus was a azhdarchoid pterodactyloid.[1] As for its classification within the family, it is unclear whether it is an azhdarchid, chaoyangopterid, or a member of a its own family in Azhdarchoidea. Azhdarchoidea is a clade of pterosaurs that existed during the Cretaceous period with a global distribution. The clade is very diverse, including the families Tapejaridae, Azhdarchidae, Chaoyangopteridae, Thalassodromidae,[2][3][4] and possibly Dsungaripteridae.[5] However, some studies have proposed the existence of another family, Alanqidae.[2][6] Azhdarchoids were edentulous and had wing proportions which were adapted to a more terrestrial life, in contrast to their heavily flight adapted relatives the Pteranodontians.[7]

Subsequent phylogenetic analyses have recovered Leptostomia as a close relative of Xericeps, within either Thalassodromidae[8] or Alanqidae.[6] The first of the below cladograms shows the results recovered by Pêgas (2024),[6] and the second shows the results recovered by Andres (2021).[8]

|

Topology 1: Pegas (2024).

|

Topology 2: Andres (2021).

|

Paleobiology

The beak of Leptostomia is unlike that of any previously described pterosaurs. Instead, it closely resembles birds that feed by probing in sediment, such as kiwis, ibises, hoopoes and snipes. These birds typically feed on invertebrates such as earthworms (in soil) or polychaete worms, fiddler crabs, or bivalves (in estuarine or marine intertidal settings). Leptostomia's prey could have been sought by a sensitive system of nerve endings capable of detecting movement at a distance.[1]

Paleoecology

During the Early to Middle Cretaceous, North Africa bordered the Tethys Sea, which transformed the region into a mangrove-dominated coastal environment filled with tidal flats and waterways.[9][10][11] The Kem Kem Beds are a sequence of fluvial and lacustrine sediments, though it has some marine sediments. Isotopes from fossils of the dinosaurs Carcharodontosaurus and Spinosaurus suggest that the Kem Kem Beds witnessed a temporary monsoon season rather than constant rainfall, similar to modern conditions present in sub-tropical and tropical environments in Southeast Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa.[12][13] The Izefouane Formation of the Kem Kem Beds where Leptostomia is known has been interpreted as a braided river system, similar to that found in the Bahariya Formation.[14][15] This river system was freshwater based on the presence of lungfishes and other freshwater vertebrates. This indicates that the Izefouane Formation had a wide variety of niches, including rivers channels, river banks, sandbars, and more.[16][1][10] These riverine deposits bore large fishes, including the sawskate Onchopristis, coelacanth Mawsonia, and bichir Bawitius.[17] This led to an abundance of piscivorous crocodyliformes evolving in response, such as the giant stomatosuchid Stomatosuchus in Egypt and the genera Elosuchus, Laganosuchus, and Aegisuchus from Morocco.[18][10][19]

Pterosaurs known from the Kem Kem Beds include the azhdarchid Alanqa, the tapejarid Afrotapejara, the possible chaoyangopterid Apatorhamphus, the possible azhdarchoid Xericeps, and the ornithocheirids Anhanguera, Coloborhynchus, Ornithocheirus, and Siroccopteryx. However, all of these pterosaurs are known from fragmentary and/or isolated remains, making their classification difficult to confirm. Many fossils have been found without overlap, such as vertebrae, notaria, or limb bones, that may belong to these taxa.[16] Dinosaurs are also known from the Kem Kem Beds, including the sauropod Rebbachisaurus, the theropods Deltadromeus, Carcharodontosaurus, and Spinosaurus, and unnamed taxa including ankylosaurs, titanosaurs, and noasaurid theropods.[20][10]

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h Smith, R.E.; Martill, D.M.; Kao, A.; Zouhri, S.; Longrich, N.R. (2020). "A long-billed, possible probe-feeding pterosaur (Pterodactyloidea: ?Azhdarchoidea) from the mid-Cretaceous of Morocco, North Africa". Cretaceous Research. 118 104643. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2020.104643. S2CID 225201538.

- ^ a b Pêgas, Rodrigo V.; Holgado, Borja; Ortiz David, Leonardo D.; Baiano, Mattia A.; Costa, Fabiana R. (2022-01-01). "On the pterosaur Aerotitan sudamericanus (Neuquén Basin, Upper Cretaceous of Argentina), with comments on azhdarchoid phylogeny and jaw anatomy". Cretaceous Research. 129 104998. Bibcode:2022CrRes.12904998P. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2021.104998. ISSN 0195-6671.

- ^ Pêgas, Rodrigo V.; Costa, Fabiana R.; Kellner, Alexander W. A. (2018-03-04). "New Information on the osteology and a taxonomic revision of The genus Thalassodromeus (Pterodactyloidea, Tapejaridae, Thalassodrominae)". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 38 (2): e1443273. Bibcode:2018JVPal..38E3273P. doi:10.1080/02724634.2018.1443273. ISSN 0272-4634.

- ^ Longrich, Nicholas R.; Martill, David M.; Andres, Brian (2018-03-13). "Late Maastrichtian pterosaurs from North Africa and mass extinction of Pterosauria at the Cretaceous-Paleogene boundary". PLOS Biology. 16 (3): e2001663. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.2001663. ISSN 1545-7885. PMC 5849296. PMID 29534059.

- ^ Andres, Brian; Clark, James; Xu, Xing (2014). "The Earliest Pterodactyloid and the Origin of the Group". Current Biology. 24 (9): 1011–1016. Bibcode:2014CBio...24.1011A. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2014.03.030. ISSN 0960-9822.

- ^ a b c Pêgas, Rodrigo V. (2024-06-10). "A taxonomic note on the tapejarid pterosaurs from the Pterosaur Graveyard site (Caiuá Group, ?Early Cretaceous of Southern Brazil): evidence for the presence of two species". Historical Biology. 37 (5): 1277–1298. doi:10.1080/08912963.2024.2355664. ISSN 0891-2963.

- ^ Smyth, Robert S. H.; Breithaupt, Brent H.; Butler, Richard J.; Falkingham, Peter L.; Unwin, David M. (2024-11-04). "Hand and foot morphology maps invasion of terrestrial environments by pterosaurs in the mid-Mesozoic". Current Biology. 34 (21): 4894–4907.e3. Bibcode:2024CBio...34.4894S. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2024.09.014. ISSN 0960-9822. PMID 39368469.

- ^ a b Andres, Brian (December 14, 2021). "Phylogenetic systematics of Quetzalcoatlus Lawson 1975 (Pterodactyloidea:Azhdarchoidea)". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 41 (sup1): 203–217. Bibcode:2021JVPal..41S.203A. doi:10.1080/02724634.2020.1801703. ISSN 0272-4634.

- ^ Hamed, Younes; Al-Gamal, Samir Anwar; Ali, Wassim; Nahid, Abederazzak; Dhia, Hamed Ben (March 1, 2014). "Palaeoenvironments of the Continental Intercalaire fossil from the Late Cretaceous (Barremian-Albian) in North Africa: a case study of southern Tunisia". Arabian Journal of Geosciences. 7 (3): 1165–1177. Bibcode:2014ArJG....7.1165H. doi:10.1007/s12517-012-0804-2. S2CID 128755145.

- ^ a b c d Ibrahim, Nizar; Sereno, Paul C.; Varricchio, David J.; Martill, David M.; Dutheil, Didier B.; Unwin, David M.; Baidder, Lahssen; Larsson, Hans C. E.; Zouhri, Samir; Kaoukaya, Abdelhadi (2020). "Geology and paleontology of the Upper Cretaceous Kem Kem Group of eastern Morocco". ZooKeys (928): 1–216. Bibcode:2020ZooK..928....1I. doi:10.3897/zookeys.928.47517. ISSN 1313-2989. PMC 7188693. PMID 32362741.

- ^ Cavin, Lionel; Boudad, Larbi; Tong, Haiyan; Läng, Emilie; Tabouelle, Jérôme; Vullo, Romain (2015-05-27). "Taxonomic Composition and Trophic Structure of the Continental Bony Fish Assemblage from the Early Late Cretaceous of Southeastern Morocco". PLOS ONE. 10 (5): e0125786. Bibcode:2015PLoSO..1025786C. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0125786. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 4446216. PMID 26018561.

- ^ Goedert, J.; Amiot, R.; Boudad, L.; Buffetaut, E.; Fourel, F.; Godefroit, P.; Kusuhashi, N.; Suteethorn, V.; Tong, H.; Watabe, M.; Lecuyer, C. (2016). "Preliminary investigation of seasonal patterns recorded in the oxygen isotope compositions of theropod dinosaur tooth enamel". PALAIOS. 31 (1): 10–19. Bibcode:2016Palai..31...10G. doi:10.2110/palo.2015.018. S2CID 130878403.

- ^ Amiot, Romain; Buffetaut, Eric; Lécuyer, Christophe; Wang, Xu; Boudad, Larbi; Ding, Zhongli; Fourel, François; Hutt, Steven; Martineau, François; Medeiros, Manuel Alfredo; Mo, Jinyou; Simon, Laurent; Suteethorn, Varavudh; Sweetman, Steven; Tong, Haiyan; Zhang, Fusong; Zhou, Zhonghe (February 2010). "Oxygen isotope evidence for semi-aquatic habits among spinosaurid theropods". Geology. 38 (2): 139–142. Bibcode:2010Geo....38..139A. doi:10.1130/G30402.1.

- ^ Smith, Joshua B.; Lamanna, Matthew C.; Lacovara, Kenneth J.; Dodson, Peter; Smith, Jennifer R.; Poole, Jason C.; Giegengack, Robert; Attia, Yousry (2001). "A Giant Sauropod Dinosaur from an Upper Cretaceous Mangrove Deposit in Egypt". Science. 292 (5522): 1704–1706. Bibcode:2001Sci...292.1704S. doi:10.1126/science.1060561. PMID 11387472.

- ^ Kellermann, Maximilian; Cuesta, Elena; Rauhut, Oliver W. M. (2025-01-14). "Re-evaluation of the Bahariya Formation carcharodontosaurid (Dinosauria: Theropoda) and its implications for allosauroid phylogeny". PLOS ONE. 20 (1): e0311096. Bibcode:2025PLoSO..2011096K. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0311096. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 11731741. PMID 39808629.

- ^ a b Smith, Roy E.; Ibrahim, Nizar; Longrich, Nicholas; Unwin, David M.; Jacobs, Megan L.; Williams, Cariad J.; Zouhri, Samir; Martill, David M. (2023-09-01). "The pterosaurs of the Cretaceous Kem Kem Group of Morocco". PalZ. 97 (3): 519–568. Bibcode:2023PalZ...97..519S. doi:10.1007/s12542-022-00642-6. ISSN 1867-6812.

- ^ Ibrahim et al. 2020, p. 184.

- ^ Holliday, Casey M.; Gardner, Nicholas M. (January 31, 2012). "A New Eusuchian Crocodyliform with Novel Cranial Integument and Its Significance for the Origin and Evolution of Crocodylia". PLOS ONE. 7 (1): e30471. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...730471H. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0030471. PMC 3269432. PMID 22303441.

- ^ Ibrahim et al. 2020, p. 180, 189.

- ^ Wilson, Jeffrey A.; Allain, Ronan (July 4, 2015). "Osteology of Rebbachisaurus garasbae Lavocat, 1954, a diplodocoid (Dinosauria, Sauropoda) from the early Late Cretaceous–aged Kem Kem beds of southeastern Morocco". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 35 (4): e1000701. Bibcode:2015JVPal..35E0701W. doi:10.1080/02724634.2014.1000701. S2CID 129846042.