Latino Futurism

Latinofuturism (also known as Latinx/Latine Futurism or Latino Futurism) is a literary, artistic, and cultural movement that reimagines Latino experiences through speculative fiction and futurist aesthetics.[1] The movement encompasses cultural productions by Chicanos, Puerto Ricans, Dominican Americans, Cuban Americans, and other Latin American immigrant populations, particularly those emerging from borderlands spaces.[1]

Latinofuturism centers Latino voices in visions of the future where Spanish, indigenous languages, and bilingualism persist alongside advanced technology.[2] The movement imagines technological innovation rooted in ancestral knowledge and collective survival strategies.[1]

History

The term builds upon Chicanafuturism, coined by scholar Catherine S. Ramírez in 2004 in her article "Deus ex Machina: Tradition, Technology, and the Chicanafuturist Art of Marion C. Martinez" in Aztlán: A Journal of Chicano Studies.[3] Ramírez examined how Chicana artists used technological materials—circuits, LEDs, and holographic materials—to reimagine traditional Catholic iconography.[3]

Academic recognition came with the 2017 publication of Altermundos: Latin@ Speculative Literature, Film, and Popular Culture, edited by Cathryn Josefina Merla-Watson and B.V. Olguín.[4] The Smithsonian Institution began documenting Latino contributions to space exploration and futurist thinking through oral history projects the same year.[5]

Characteristics

Temporal structures

Latinofuturist works employ non-linear temporal structures derived from circular time concepts in Mesoamerican cultures.[6] Past, present, and future are presented as interconnected layers where ancestral knowledge informs technological innovation.[2]

Rasquachismo

The movement employs rasquachismo, a working-class Chicana/o aesthetic of creative resourcefulness.[1] This manifests in characters who create technology from salvaged materials, informal economies that persist into the future, and DIY approaches to scientific discovery.[7]

Theoretical influences

The movement draws from José Esteban Muñoz's concept of "queer futurity," which scholars identify as a key framework for Latino speculative fiction.[8] Latinofuturist works create "altermundos" (alternative worlds) that address labor, migration, and globalization effects on borderlands communities.[7]

Themes

Migration and border crossing

Migration functions as a central metaphor in Latinofuturist works, with borders reimagined as technological interfaces, temporal boundaries, or spaces of transformation.[1] Characters frequently navigate between worlds, whether physical borders, digital realms, or temporal dimensions.[2]

Labor and technology

The movement addresses the relationship between Latino workers and technology, from maquiladora labor to virtual work.[2] Works like Lunar Braceros extend historical labor patterns into futuristic contexts, examining how exploitation persists across technological advancement.[9]

Hybrid identities

Latinofuturism explores hybrid identities through technological and cultural fusion. Ken Gonzales-Day's 2001 concept of "Choloborg" combines cholo identity with Donna Haraway's cyborg theory to reclaim marginalized identities through technology.[10] These hybrid figures challenge boundaries between human and machine, traditional and futuristic.

Environmental futures

Many Latinofuturist works address environmental justice and climate change through narratives that connect local environmental struggles with global climate systems.[3] These stories feature water scarcity, climate migration, water rights activism, and renewable energy innovations rooted in traditional ecological knowledge and indigenous agricultural practices. Works explore how communities develop both technological and spiritual solutions to ecological crises, often imagining futures where ancestral knowledge informs climate adaptation strategies. Early Chicanafuturist works like Marion C. Martinez's art highlighted these themes by incorporating discarded computer parts to expose regions' histories as dumping grounds for technological waste and environmental injustice.[3]

Language and cultural preservation

The persistence of Spanish, indigenous languages, and code-switching in futuristic settings represents resistance to cultural erasure.[2] Multilingualism functions as both survival strategy and technological advantage in these narratives.

Decolonial temporalities

Latinofuturist works reject linear Western time, employing Mesoamerican circular time concepts where past, present, and future coexist.[6] Ancestors appear as active participants in future scenarios, and pre-Columbian technologies resurface in advanced forms.

Literature

Ernest Hogan's 1999 novel Smoking Mirror Blues depicts a futuristic East Los Angeles where Aztec deities manifest through advanced technology.[9] The protagonist, a lowrider mechanic, discovers his car modifications channel Tezcatlipoca.

Rosaura Sánchez and Beatrice Pita's Lunar Braceros 2125-2148 imagines Mexican workers traveling to lunar mining colonies, extending the historical Bracero Program into space.[9] The novella addresses labor exploitation and immigration policy through science fiction.

Visual arts

Marion C. Martinez creates installations combining Catholic iconography with electronic art.[3] Her work "Guadalupe, Queen of Heaven" depicts the Virgin's traditional blue mantle as flowing digital data streams.

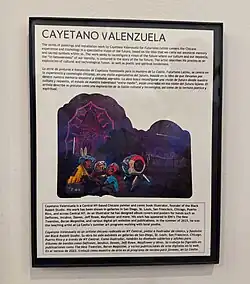

Contemporary artist Cayetano Valenzuela paints Latino children as space explorers and inventors.[11] His 2023 series "Future Ancestros" features young protagonists in space suits decorated with Mesoamerican-style designs, and Mexican cultural figures like La Virgen de Guadalupe.[5]

In 2022, Ken Gonzales-Day created public installations combining ancient Mesoamerican figures with digital manipulation. His work for the LA Metro stations features objects from LACMA's collection transformed through digital technology, creating what he describes as "portals" between past and future.[10]

Comics and graphic narratives

Zeke Peña's comic series "Funkterra" depicts post-apocalyptic El Paso where the Rio Grande has become a digital river of information.[12] The series explores how border communities adapt to climate change while maintaining cross-cultural connections, drawing importance to the Rio Grande.

Film

Director Alex Rivera's Sleep Dealer (2008) imagines futures where globalization and technology reshape Latino labor and migration patterns.[2] The film features cyberpunk elements addressing maquiladora labor and virtual reality work.

Recognition

The Library of Congress officially recognizes Latinx Futurism as a distinct literary movement related to Afrofuturism and Indigenous Futurisms.[2]

In 2023, La Casita Cultural Center at Syracuse University hosted "Futurismo Latino – Cultural Memory and Imagined Worlds."[11][5][12]

The National Endowment for the Arts has funded Latinofuturist projects since 2020, including community workshops that teach STEAM education through science fiction writing and digital art creation.[2]

Relationship to other movements

Afrofuturism

Latinofuturism shares with Afrofuturism concerns about imagining futures for marginalized communities, but emphasizes themes of language preservation, border crossing, and environmental migration.[1] While Afrofuturism foregrounds the African diaspora and the legacy of slavery, Latinofuturism focuses on migrations within and across the Americas.[1]

Afrofuturism often explores space travel as an escape from earthly oppression.[13] Latinofuturism more frequently imagines technological solutions to terrestrial problems like water scarcity and climate adaptation. Isabel Millán argues the movements "become tightly knit when considering Afro-Latina/o speculative productions."[1]

Indigenous Futurisms

Both Latinofuturism and Indigenous Futurisms challenge linear Western concepts of time and emphasize traditional ecological knowledge.[2] Indigenous Futurisms, coined by Anishinaabe scholar Grace L. Dillon, involves "biskaabiiyang" (an Anishinaabemowin word meaning "returning to ourselves").[14]

According to Dillon, this involves "discovering how personally one is affected by colonization, discarding the emotional and psychological baggage carried from its impact, and recovering ancestral traditions in order to adapt in our post-Native Apocalypse world."[15]

For the Māori, time concepts "are interconnected, interdependent and complex, with multi-layered and multi-faceted dimensions."[16] Indigenous African approaches similarly emphasize circular rather than linear temporalities.[16] Latinofuturism deploys Mesoamerican circular time concepts in similar ways.[6]

Latinofuturism focuses specifically on mestizo and immigrant experiences rather than indigenous sovereignty.[2]

See also

- Afrofuturism

- Border art

- Chicanafuturism

- Chicano literature

- Gloria Anzaldúa: Borderlands/La Frontera

- Indigenous Futurisms

- Latino science fiction

- Magical realism

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h Merla-Watson, Cathryn (2019). "Latinofuturism". Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Literature. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780190201098.013.648. ISBN 978-0-19-020109-8. Retrieved 2025-06-30.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "Latinx Futurism". Library of Congress. Retrieved 2025-06-30.

- ^ a b c d e Ramírez, Catherine S. (2004). "Deus ex Machina: Tradition, Technology, and the Chicanafuturist Art of Marion C. Martinez". Aztlán. 29 (2): 55–92. doi:10.1525/azt.2004.29.2.55.

- ^ "Altermundos". UCLA Chicano Studies Research Center. 5 April 2017. Retrieved 2025-06-30.

- ^ a b c "La Casita's exhibit "Futurismo Latino: Cultural Memory and Imagined Worlds" continues into next year". WAER. October 8, 2023. Retrieved 2025-06-30.

- ^ a b c Bowles, David (2024). "Toward a Mexican American Futurism". In Taylor, Taryne Jade; Lavender, Isiah; Chattopadhyay, Bodhisattva; Dillon, G. L. (eds.). The Routledge Handbook of CoFuturisms. Routledge. pp. 337–339. ISBN 9780367330613.

- ^ a b Aldama, Frederick; González, Christopher (2018). Latinx Studies: The Key Concepts. Routledge. p. 15. doi:10.4324/9781315109862.

- ^ Merla-Watson, Cathryn Josefina; Olguín, B. V. (2015). "Introduction: ¡Latin@futurism Ahora! Recovering, Remapping, and Recentering the Chican@ and Latin@ Speculative Arts". Aztlán: A Journal of Chicano Studies. 40 (2): 135–145. doi:10.1525/azt.2015.40.2.135.

- ^ a b c "Postethnicity and Antiglobalization in Chicana/o Science Fiction". EScholarship. University of California. doi:10.5070/T891041526. Retrieved 2025-06-30.

- ^ a b Gonzales-Day, Ken (2022). "Latinx Futurisms in (Public) Space". The Latinx Project at NYU. Retrieved 2025-08-10.

- ^ a b "La Casita to Celebrate Hispanic Heritage Month With New Exhibition". Syracuse University News. September 12, 2023. Retrieved 2025-06-30.

- ^ a b Brockington, Sydney (September 19, 2023). "Syracuse welcomes Latine Heritage Month with 'Futurismo Latino' exhibit". The Daily Orange. Retrieved 2025-06-30.

- ^ White, Devin T.; McGee, Ebony O. (2021). "Afrofuturism Unveiled". Science for the People. Retrieved 2025-08-10.

- ^ Dillon, Grace; Neves Marques, Pedro (2021). "Taking the Fiction Out of Science Fiction: A Conversation about Indigenous Futurisms". e-flux (120). Retrieved 2025-08-10.

- ^ Vowel, Chelsea (2022). "Writing Toward a Definition of Indigenous Futurism". Literary Hub. Retrieved 2025-08-10.

- ^ a b Terry, Naomi; Castro, Azucena; Chibwe, Bwalya; Karuri-Sebina, Geci; Savu, Codruța; Pereira, Laura (2024). "Inviting a decolonial praxis for future imaginaries of nature: Introducing the Entangled Time Tree". Science Direct: Invironmental Science and Policy. 151: 103615. doi:10.1016/j.envsci.2023.103615.