Land Gate, Famagusta

| Land Gate | |

|---|---|

Land Gate viewed from outside the walled city | |

Location within Cyprus | |

| General information | |

| Architectural style | Venetian |

| Town or city | Famagusta |

| Country | |

| Coordinates | 35°07′16″N 33°56′22″E / 35.121189°N 33.939567°E |

| Construction started | 1508 |

| Design and construction | |

| Architect(s) | Marco Paulo, Giangirolamo Sanmicheli |

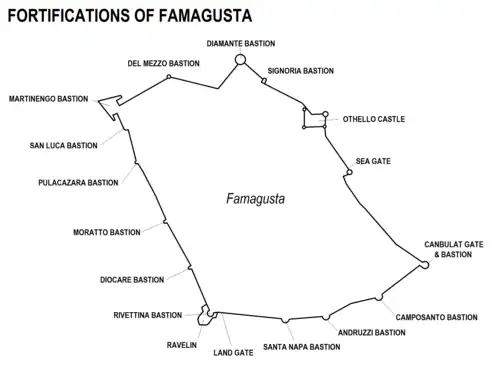

The Land Gate, Famagusta, (Turkish: Kara Kapısı; Greek: Πύλη της Ξηράς; Italian: Porta di Limisso) is a gate in the Walls of Famagusta, Cyprus. It was the entrance gate to the city for all land traffic, while the Sea Gate served maritime traffic. The Land Gate's associated tower (Limassol tower, Ak Kule (white tower) or Ravelin bastion), which dates back to the Genoese period, originally contained the gate and parts of the old gate still exist. However, this was devasted during the Siege of Famagusta of 1570-1571 and the victorious Turks cut a new opening in the walls by the side of the tower.

Description

The old city of Famagusta is surrounded by walls which are around 50 ft (15 m) high and 27 ft (8.2 m) thick. Until the mid 20th century there were two gates, the Sea Gate and the Land Gate.[1] As part of the development of the port the Arsenal Gate was opened to land traffic in 1933. Then in 1965 the North Gate was opened by the Turkish Municipality of Famagusta. The original Sea Gate of 1310 is not used and has been undergoing restoration. Although three other openings, in the sea wall were cut by the British in 1903 for access to the newly developed port these have been superseded.[2]

The original Venetian land gate was replaced in the Ottoman period by a gate just to the east, which utilises a 15th century gun chamber. The original gate can be seen a few yards on the left when entering the city.[1] [3]

Outside the walls of Famagusta is a deep 'fosse or ditch, 25 ft (7.6 m) deep or more and 140 ft (43 m) wide. This formidable obstacle is hewn out of solid limestone rock, which was used to construct the walls.[3] This ditch is traversed by a narrow stone bridge upon arches, after which the narrow road passes through a massive gateway with a Portcullis.[4] Formerly a double Drawbridge connected the stone bridge to the entrance archway.

The original land gate retains its entrance from inside the city, but the passage through to the outside no longer exists. At the entrance is a large 30 ft (9.1 m) high archway, inside of which are faint traces of large square panels of frescoed plaster containing coats of arms.[5][1] Beneath the tower are two Venetian coats-of arms in fresco. At the end of the passage leading out on to the original outer gate, are the arms of the Knights of Jerusalem and Cyprus.[3]

The original land gate went through a tower which was protected from the outside by a Ravelin, a detached angular outwork and fortification. After severe damage in the siege of 1571, the Ravelin was filled in by the victorious Turks changing it into a sort of secondary bastion, by closing the original gates with masonry, filling the interior with earth, and erecting two Caponier structures at the sides of the formerly detached outwork.[6][5]

History

Genoese

The Genoese captured Famagusta in 1373 and a treaty of February 1383 granted the Republic of Genoa the city of Famagusta and a territory two leagues around it. They retained it for 91 years until the city was recaptured by James II of Cyprus in 1464. However, on his death 10 years later it came under Venetian domination.[7][8] In this period the main gate, just west of the present land gate was known as “Porta di Limisso” - Limassol Gate.[9] It was on a salient at the south-west corner of the city walls. It has been documented since the Genoese period, but probably dates back to time of the original Lusignan walls.[6] Commerce on the landward side passed through the Limassol Gate, with the Genoese authorities monitoring the entry and exit.[10]

The Limassol gate preserves traces of the Genoese period.[11] Research by Nicolas Faucherre indicates the Limassol gate tower was octagonal with narrow 27 m (89 ft) sides protected by a moat cut into solid rock.[6]

There was much damage caused by artillery when the city was recaptured by James II.[6]

Venetian

The Land Gate was completely rebuilt by the Venetians. A new defensive structure was built outside and detached from the outer wall in a symmetrical horseshoe shape, 159 m (522 ft) long and 48 m (157 ft) wide. This type of structure is known as a Ravelin and was designed by Marco Paulo.[6][5]

Work began in 1508 and with the demolition of the freestone walls and the previous tower, and plans to relocate the gate. The project continued for several decades, although the Ravelin was considered defensible as early as 1511 and was officially declared complete in 1529. The cost was over 12,000 ducats.

The Ravelin protected a gate and drawbridge located on the left side (facing outwards). A planned second drawbridge on the right may not have been built. Earthworks continued on the left side on the curtain wall towards the next tower, Santa Nappa, in 1519. On top of the gate tower a raised platform was built with access ramps. An inscription indicates that works completed in 1544. The Ravelin is a rare survival of an earlier system of artillery, as this system was completely condemned by the end of 16th century.[6][5]

Outside the walls there was a deep ditch hewn out of solid rock which was filled with sea water.[4]

About 20 years later additional work was done especially with the coming of war in 1570. Improvements were made to the protection of the gate tower.[6][5]

During the siege the military defence engineer Girolamo Maggi invented machines to defend Famagusta and repaired damage.[12]

Ottoman Turkish

In the siege of 1571, the ravelin was the part of the fortifications most contested and was completely destroyed by artillery and mines. When the Turks repaired the fortifications after the siege, the ravelin was merged with the tower, which they named Ak Kule (white tower). A new gate was cut through the wall a few yards east to replace the previous one through the tower [6][5] and a decree dated 6 August 1572 ordered the opening of this new gate and the construction of a bridge in front of it.[9] This was a narrow stone bridge upon arches, provided with a double drawbridge leading to up to the gate itself, which had a Portcullis in its massive archway.[4]"

During Turkish rule the only openings into the city were the Land Gate and the Sea Gate. In 1745 the British Consul at Aleppo observed that the Turks permitted no Christian to ride into the city and he was obliged to dismount and walk along the bridge.[13][14] The gates were locked every night, as was observed by the British Commissioner of Famagusta in 1878.[15]

Beside the Land Gate was the city prison. It was located in the structure of the tower. It had a court that was open and users of the gate could pass into the prison-yard without hindrance.[16]

British

In 1878 Cyprus came under British rule, although under almost nominal Ottoman suzerainty. The Ottoman practice of controlling entrance into the city and closing the gates at night had discontinued by the end of the following year.[15] Initially the Land Gate was still the only gate for land traffic into the city. The ditch which had been filled with sea water had become silted up and consequently a malarial hazard. So trees were planted in the ditch to absorb water and it was also drained.[4]

From 1935 Theophilus Mogabgab organised the clearing of the Ravelin area and then the restoring of the gates and arcades in 1937.[6]

See also

References

- ^ a b c "Romantic Cyprus", 17th ed., by Kevork Keshishian, publ. Romantic Cyprus Publications, Famagusta 1993, ISBN 9963-571-25-5; pp.193, 197

- ^ ”The Walled City of Famagusta - A Compendium of Preservation Studies, 2008–2012”, publ. World Monuments Fund, New York, NY, date: 2012. ISBN 0-9858943-4-2; ISBN-13 978-0-9858943-4-4. Part 1 - A Framework for Urban Conservation and Regeneration, by Dr. Randall Mason, Dr. Ege Ulvea Tumer and Ayşem Kilinç Ünlü, p.18

- ^ a b c "Handbook to the Mediterranean : Its Cities, Coasts, and Islands", by Lieut. Col. Sir R. Lambert Playfair, 3rd ed., publ. J. Murray, London, 1892; p.185

- ^ a b c d "Cyprus: A Short Account of its History and Present State", by Col. A. O. Green, publ. M. Graham Coltart, Kilmacolm, Renfrewshire (Scotland), 1914; p.93

- ^ a b c d e f "A Description of the Historic Monuments of Cyprus" by George Jeffery, Architect. Publ. Government Printing Office, Famagusta, 1918; pp.106-108

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "Porte de Limassol / Ravelin, Famagouste", by Gilles Grivaud, Frankika on the website of the École Française d'Athènes: frankika.efa.gr/fr/node/14059 - retrieved July 2025

- ^ "King James II of Cyprus and his multicultural mercenaries", by Nicholas Coureas, in "Mercenaries and Crusaders", ed. by Attila Bárány, publ. Debrecen, 2024 ISBN 978-963-490-554-7 website: www.academia.edu/119628865/King_James_II_of_Cyprus_and_his_Multicultural_Mercenaries - retrieved July 2025. pp.273-274

- ^ "Crusading and Trading between West and East", ed.Sophia Menache, Benjamin Z. Kedar, Michel Balard, publ. Routledge, London, 2018, ISBN9781315142753. Chapter 9 "New documents on Genoese Famagusta", by Michel Balard. Abstract from web site: doi.org/10.4324/9781315142753 retrieved July 2025

- ^ a b "Tari̇hi̇ Mağusa Kenti̇ ve Tahkimati" (The Historic City of Famagusta and its Fortifications), by Tuncer Bağişkan, website: www.yeniduzen.com/tarihi-magusa-kenti-ve-tahkimati-26004h.htm - Retrieved July 2025

- ^ "La ville et la mer - L’exemple de Famagouste", by Catherine Otten-Froux; retrieved from web site: books.openedition.org/pup/25519 July 2025; pp. 177-196

- ^ "L'enceinte urbaine de Famagouste", by Nicolas Faucherre, publ. Institut de France, 2006,ISSN 0398-3595, in Mémoires de l'Académie des inscriptions et belles-lettres, ISSN 0398-3595; pp.307-350. See article Abstract on the French academic open archive HAL (Hyper Articles en Ligne) shs.hal.science/hal-00101465/ - retrieved July 2025

- ^ Promis, Carlo (1862). "Vita di Girolamo Maggi d'Anghiari" (PDF). Miscellanea di Storia Italiana. 1: 105–143. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-03-12. Retrieved 2006-03-13.

- ^ "Travels through different Cities of Germany, Italy, Greece and several parts of Asia", by Alexander Drummond, British Consul at Aleppo, printed by W. Strahan, Lomdon, 1754; p.185 (Letter VI dated 18 July 1745)

- ^ "Excerpta Cypria - Materials for a History of Cyprus", translated and transcribed by Claude Delaval Cobham (ex-Commissioner of Larnaca), publ. by Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 1908; p.274 (excerpt of Drummond letter VI)

- ^ a b "Report by Her Majesty's High Commissioner for the Year 1879" (UK Parliament Command paper), Printed by Harrison and Sons, London, 1880; section provided by James Inglis, Commissioner. Capt. T.A.S. Inglis, Commissioner of Famagusta ; p.81

- ^ "British Cyprus", by W. Hepworth-Dixon, publ. Chapman & Hall, London, 1879; p.293