Lamentation (Annibale Carracci)

Lamentation was an oil-on-canvas painting executed ca. 1587–1590 by the Italian Baroque painter Annibale Carracci, destroyed with other Carracci works such as Danaë at Bridgewater House in May 1941 during the London Blitz. Prints and copies of it survive, the best being those by the Ferrara painter Francesco Naselli now in Mantua's city library.

History

The painting's commissioner is unknown, since its first mention in the historical record dates to 1616, when it was given by a notable in Reggio Emilia to San Prospero Basilica in Reggio Emilia. Carracci had spent some time in that city during the 1580s and produced several works there, none still in their original locations, leading to the commonly held theory that Lamentation was also produced in the city.[1] It then passed into the Orleans Collection before going back on the market upon the French Revolution and reaching England. There it reached its final home at Bridgewater House, London residence of the Earl of Ellesmere, who had inherited the collection of which Lamentation had become a part.

Carlo Cesare Malvasia speaks of the painting in laudatory terms, and Ludovico Carracci also reportedly intervened on the Lamentation in Reggio Emilia for some final touches.[2]

Description and style

Annibale explored the theme of the "Pietà many times throughout his artistic career. However, the "Lamentation" in Reggio, both iconographically and compositionally, displays significant differences compared to other Carracci versions dedicated to the theme.

In the Reggio canvas, Christ is completely stretched out on the ground, while, in Annibale's other works, Jesus is always supported by the Virgin Mary, sometimes with the help of some of the other characters who participated in his Psssion. This is, in fact, a rather rare iconographic option in painting, even if a relevant example in this sense is provided by the fresco of the Deposition which is part of the Passion cycle painted by Pordenone, for the Cremona Cathedral, between 1520 and 1521.[3]

It is a precedent, moreover, most likely known to Annibale, who likely stayed in Cremona, his father's hometown. Pordenone's fresco, therefore, is a possible model for the lost "Lamentation" of San Prospero.[3] Other works, however, seem to have had a more direct influence on this canvas by Carracci.

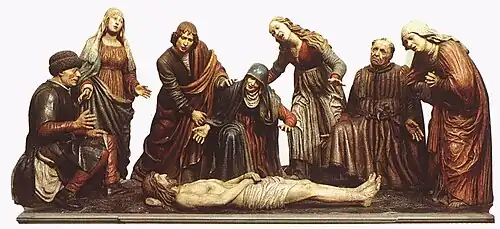

In fact, if the theme of Christ's body completely stretched out on the ground was rather rare in painting, it was instead frequent in polychrome terracotta sculptural groups of the late 15th and early 16th centuries, particularly widespread in Northern Italy and in Emilia in particular.

Notable examples of such compositions – associated with the lost canvas of San Prospero – are the Lamentation by Niccolò dell'Arca, in the Bolognese church of Santa Maria della Vita, and that by Guido Mazzoni in the church of San Giovanni Battista in Modena.[3] From these groups Annibale seems to have borrowed, in addition to the position of Christ, also the strong emotional charge that pervaded his destroyed Lamentation.[3]

In Annibale's composition, Jesus lies on the ground, on a shroud that is in turn placed on a stone slab: it is the stone of anointing to which Christ's body will be subjected, as was the custom among the Jews of the time, before being buried. Particularly effective is the nude of the deposed figure, most likely taken from life.[1] Mary Magdalene delicately supports his left hand and seems to be preparing to clean the wound caused by the nail using a lock of her hair.

The Virgin, however, is about to faint from the pain and must be supported by the other pious women. The group of Mary in a swoon supported by the women shows similarity to the similar depiction in the Christ Taking Leave of His Mother by Correggio.[1]

On the opposite side, Saint John the Evangelist expresses his dismay by desperately spreading his arms, while his gaze is turned to Mary. At the top, three angels, supported by clouds, another reminiscence of Correggio, close the composition.

The canvas is characterised by a diagonal development, described by the body of Jesus, which brings the scene closer to the viewer and heightens its emotional impact.[3] The diagonal arrangement allows the sharp edge of the stone on which the deposed Christ lies to pierce the pictorial space and enter the real one. This device anticipates the same solution followed by Caravaggio in his The Entombment of Christ.[1]

Gallery

-

Niccolò dell'Arca, Lamentation (detail), 1463–1490, Santuario di Santa Maria della Vita, Bologna

Niccolò dell'Arca, Lamentation (detail), 1463–1490, Santuario di Santa Maria della Vita, Bologna -

Guido Mazzoni, Lamentation, 1476–1479, church of San Giovanni Battista, Modena

Guido Mazzoni, Lamentation, 1476–1479, church of San Giovanni Battista, Modena -

Correggio, Christ Taking Leave of His Mother, circa 1513, National Gallery, London

Correggio, Christ Taking Leave of His Mother, circa 1513, National Gallery, London -

References

- ^ a b c d (in Italian) Alessandro Brogi, in Annibale Carracci, Catalogo della mostra Bologna e Roma 2006-2007 (edited by D. Benati and E. Riccomini), Milano, 2006, p. 180.

- ^ Carlo Cesare Malvasia, Felsina Pittrice, 1676, Volume I, p. 282 (in the 1841 reprint of the edition of Felsina edited by Giampietro Zanotti).

- ^ a b c d e Donald Posner, Annibale Carracci: A Study in the reform of Italian Painting around 1590, Londra, 1971, Vol. I, p. 40.