Lake Ospedaletto

| Lake Ospedaletto Lake Minisini | |

|---|---|

The lake seen from the military road of Forte di Monte Ercole | |

| Location | Gemona del Friuli, Province of Udine, Friuli-Venezia Giulia, Italy |

| Coordinates | 46°16′12″N 13°07′48″E / 46.27000°N 13.13000°E |

| Type | Periglacial |

| Primary inflows | Rio del Giago |

| Primary outflows | None |

| Surface area | 2 ha (4.9 acres) |

| Surface elevation | 208 m (682 ft) |

Lake Ospedaletto (in Friulian Lât di Ospedalét), also known as Lake Minisini, is a small prealpine water body of periglacial origin located near the hamlet of Ospedaletto (Gemona del Friuli) in the municipality of Gemona del Friuli, Province of Udine, in Friuli-Venezia Giulia, Italy.

Etymology

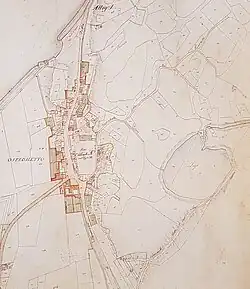

The lake takes its name from the nearby settlement of Ospedaletto. The designation Lake Minisini is an anthroponym derived from the name of one of the local families that owned it. It became established for use in topographic maps from the mid-19th century.[1][2]

Physical geography

Located near the northern end of the flat sector known as Campo di Osoppo – Gemona,[N 1] north of the Venetian Plain,[3] at an elevation of 208 m above sea level, the lake lies at the foot of gentle, low hills (Monte Cumieli, 571 m above sea level) – which are the western extension of the Chiampon-Stol mountain range.

The ridges of the small hills surrounding the water body shield it to the north from the cold currents flowing through the Tagliamento valley; to the west and south, they protect it from the noise of the densely anthropized plain.

Nestled in a harmonious landscape of forests interspersed with well-maintained grassy clearings, the lake represents one of the last examples of a periglacial lake in Friuli and is the largest natural basin in the Giulian Prealps.[4]

Geology

Geologically, the area exhibits characteristics of high dynamism, being close to the so-called Periadriatic Thrust, the event considered responsible for the high seismicity of the area.[3]

The rocks in the area are all of sedimentary origin.

They consist of a base of limestones and dolomites from the Mesozoic era, from which the soil formation process began. The oldest rocks date back 200 million years (grey dolomites from the Triassic) whose stratification is very evident in the surrounding hills.

The dolomitic limestones from the Jurassic constitute the majority of the substrate in the affected areas. These give way to more cherty limestones moving away from the basin along the road leading to Sella di Sant'Agnese.

In the northeastern part of the lake, not very visible as they are mostly covered by recent accumulations of slope debris, there are some glacial deposits that show slight cementation.

Morphology of the territory and landscape

The action of the glacier that occupied the entire Tagliamento valley until the end of the Würmian period (about 10,000 years ago) left very evident traces in the Ospedaletto area: the rounded whaleback profile[N 2] of the small ridges overlooking the village or the presence of erratic boulders with a composition not traceable to the rocks present in the area.

The basin of the lake was formed precisely due to the exarasion action of the moving ice. It is estimated that at this point, its thickness reached 900 m above sea level (about 700 m above the current ground level). In its movement downstream, after crossing Monte Cumieli, it descended with greater erosive action, forming depressions in the underlying rock layer. Following the glacier's retreat, the natural disintegration of the rock formations covered the existing moraines with screes known as slope deposits.

The small inflow stream is responsible for the alluvial fan that causes filling in the northeastern side, giving the basin its typical crescent shape.

Between the lake and Monte Ercole, there are two depressions of similar origin (called Lunghinâl and Broili) which, after undergoing progressive infilling, partly artificial, are used for agricultural cultivation due to their flat nature.

This geologically relatively recent action has modified a territory that, by its nature, is constantly evolving due to the strong tectonic disturbances characterizing the region.

Anthropization

With the exception of the nearby route of the Pontebbana railway (reworked in the 1980s to allow its doubling), human action has not excessively altered the surrounding landscape.

There are some dirt roads providing access to properties for forestry activities, agriculture is limited to mowing the surrounding meadows, and buildings are extremely rare. In the early 20th century, the area was subject to works for the construction of the Forte di Monte Ercole, with the creation of the military road to the saddle of Sant'Agnese.

Hydrography

The lake has no surface outflows. Its only inflow is the very small watercourse with a torrent regime called Rio del Giâgo.

The surface area and level depend significantly on the seasonality of water inputs.

The average is approximately a depth of 1 meter and an extent of 2 hectares.

The karstic nature of the rocky layers of the basin allows, on one hand, a source of supply through some springs (on the southeastern and probably northern sides), and on the other, a likely underground outflow of water through fissures on the southern side. Additionally, there is an exceptional natural connection of erosive origin with the artificial channel of the Roggia dei Molini,[2] (it is likely that the course of the water, dating back to the 13th century, was dictated by the need to capture this source near the settlement of Ospedaletto).[5]

The connection is about 350 meters in a straight line and allowed flow in both directions to or from the lake depending on the levels, through a system of sluices, as the difference in elevation between the two entrances is practically negligible.[6] In the 1980s, the passage was precautionarily closed to avoid potential contamination and prevent excessive draining of the lake.

(See the pollution episode of the Tagliamento in 1987, following the spill of chemical substances into the inflowing Fella River.[7])

Climate

.jpg)

The climate is strongly influenced by the morphology of the territory. The area is subject to almost constant ventilation (sometimes strong), which results in the near-total absence of foggy or hazy days in the cold season. Conversely, in the summer months, sultry heat days are equally rare. The rainiest seasons are spring and autumn: the nearby ridges of the Giulian Prealps, blocking the path of low-pressure systems coming from the Mediterranean, cause the intense precipitations that characterize these periods. Summers, which do not experience the extreme temperatures of the Venetian Plain, are mitigated by frequent showers. This makes the area one of the rainiest in Italy (about 2,000 mm/year in Gemona, over 3,000 mm/year in nearby Uccea).[8]

Flora and fauna

.jpg)

Flora

The favorable position allows the survival of numerous thermophilic species of a sub-Mediterranean type.

The surrounding woodlands are populated by highly heterogeneous vegetation composed of flowering ash, European hop-hornbeam, hornbeam, downy oak, linden, hazel, chestnut, elm, sorbus, and other species.

In the undergrowth, it is possible to find occasionally interesting specimens such as fire lily, martagon lily, pale birthwort, Pulmonaria australis, blue-eyed Mary, dog's-tooth-violet, and various species of orchid.

The floristic peculiarities closely tied to the presence of the lake include: floating mats (white waterlily and bulrush), sedge meadows (Carex elata), common club-rush, reed beds (common reed), mare's-tail, varieties of the genus pondweed, and other species typical of wetlands, some of which, despite their wide range, are considered rare.[5][9][10][11]

Fauna

.jpg)

The biotope hosts a significant number of species that find ideal conditions for reproduction or as a stopover for migratory birds.

Among the invertebrates, which abound in variety and number, notable are the rare dragonflies Leucorrhinia pectoralis and Sympetrum vulgatum.

The typically lacustrine fauna is represented by some recently introduced fish species such as tench, pumpkinseed, and carp.

Amphibians are well represented, including species such as green frog, red frog, yellow-bellied toad, some toad species (common toad, green toad), newt, and fire salamander.

Among aquatic predators, the grass snake is abundant.

The surrounding territory hosts a variety of micromammals such as voles, edible dormice, squirrels, and their predators, both mammalian (foxes, mustelids, and rarely the wildcat) and raptorial (common buzzard and various species of owls). Also not uncommon is the presence of ungulates, represented in fair numbers by roe deer and wild boar.[5]

The avifauna present, in addition to the aforementioned species, includes the common moorhen and the mallard, which nest permanently.

Migratory species or those reported include: little grebe, great crested grebe, coot, honey buzzard, grey heron, Eurasian bittern, little bittern, green woodpecker, great spotted woodpecker, wryneck, black-crowned night heron, teal, common snipe, kingfisher, water rail.[11][12]

Protected areas and natural parks

The constant presence of water and the relatively sheltered position have allowed the development of a biological complexity that, combined with the uniqueness of the lean meadow environments of the Rivoli Bianchi, is of significant value despite the relative proximity to human activities.

The importance of the biotope is recognized and protected at the European level as a special area of conservation (Natura 2000 Site IT3320013 Lago Minisini and Rivoli Bianchi).[9][10]

The Lake Ospedaletto is included in the list of geosites of the Friuli-Venezia Giulia region as it represents one of the last examples of a periglacial lake in Friuli.

History and economy

The lake does not belong to the public water domain and is divided into slices of private ownership.

The introduction of fish species for fishing purposes has been a long-standing practice.

Until the early 20th century, the extraction of peat, used as a fertilizer, was common. This activity helped delay the natural infilling process of the basin, mainly due to the contribution of aquatic and surrounding plant material. With the cessation of this practice and the proliferation of the alien species Phragmites australis, (which was absent until the mid-20th century), transformation into a peat bog seemed imminent.[11]

On 26 August 1944, in two waves of air raids by Allied forces, the communication routes north of the village were targeted. The first attack severely damaged the viaduct of the railway. The second mistakenly used the dust cloud from the first bombing, which had been shifted by the wind, as a reference, dropping bombs near the lake.[14] From this episode, the possible presence of unexploded ordnance within the water body has been inferred.

During the winter of 2010–2011, the basin underwent environmental restoration, ordnance clearance, and vegetation improvement works on the shores to recreate open water spaces and limit the input of plant material.[15]

The lake, thanks to convenient access and redevelopment and promotion efforts (it is easily reachable via a short variant of the Alpe Adria cycle path passing through the nearby settlement of Ospedaletto), together with other points of interest in the area, offers various itineraries for hiking, naturalistic, and historical tourism. It is also a reference point for the leisure time of local residents, for educational activities for schools, and for training for athletes in various disciplines.[15]

Notes

References

- ^ Lorenzi, Arrigo (1897). "VIII". Il lago di Ospedaletto nel Friuli [The Lake of Ospedaletto in Friuli] (in Italian). Udine: In Alto – Società Alpina Friulana.

- ^ a b Marinelli, Olinto (1912). Guida delle Prealpi Giulie [Guide to the Giulian Prealps] (in Italian). Udine: Società Alpina Friulana.

- ^ a b Sgobino, Federico; Mainardis, Giuliano; Chiussi, Enrico (1983). Geologia, flora e fauna del Gemonese [Geology, flora, and fauna of the Gemona area] (in Italian). Gemona: Comunità Montana del Gemonese. p. 49.

- ^ "La scheda su Geositi regione FVGi" [Datasheet on FVG region geosites] (PDF) (in Italian).

- ^ a b c Mainardis, Giuliano; Sgobino, Federico; Tondolo, Maurizio (1992). Parco naturale delle Prealpi Giulie, Comune di Gemona del Friuli [Natural Park of the Giulian Prealps, Municipality of Gemona del Friuli] (in Italian). Gemona del Friuli. pp. 45–50.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Mainardis, Giuliano; Sgobino, Federico; Tondolo, Maurizio (1992). Parco naturale delle Prealpi Giulie, Comune di Gemona del Friuli [Natural Park of the Giulian Prealps, Municipality of Gemona del Friuli] (in Italian).

- ^ Alessandra Longo (3 January 1987). "Colla tossica nel Tagliamento ha ucciso migliaia di pesci" [Toxic glue in the Tagliamento killed thousands of fish] (in Italian).

- ^ "Copia archiviata" [Archived copy] (PDF) (in Italian). Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 April 2020.

- ^ a b di Bernardo, Franco (2012). Camminando… verso Sant'Agnese e Ospedaletto [Walking… towards Sant'Agnese and Ospedaletto] (in Italian). pp. 50–56.

- ^ a b Sgobino, Federico; Mainardis, Giuliano; Chiussi, Enrico (1983). Geologia, flora e fauna del Gemonese [Geology, flora, and fauna of the Gemona area] (in Italian). Gemona. pp. 281–284.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b c Mainardis, Giuliano; Candolini, Renato (2001). Glemone – Numero Unico 78º Congresso SFF [Glemone – Special Issue 78th SFF Congress] (in Italian). Udine: Società Filologica Friulana. pp. 39–42.

- ^ Mainardis, Giuliano; Sgobino, Federico; Tondolo, Maurizio (1992). Parco naturale delle Prealpi Giulie, Comune di Gemona del Friuli [Natural Park of the Giulian Prealps, Municipality of Gemona del Friuli] (in Italian). Gemona del Friuli. pp. 48–50.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Stoch, Fabio. Atti del convegno "Un Lago nel Parco" [Proceedings of the conference "A Lake in the Park"] (in Italian). Gemona.

- ^ Londero (2014). Ospedaletto dai rivoli Bianchi alla Liberazione [Ospedaletto from the Rivoli Bianchi to Liberation] (in Italian). Gemona. p. 19.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b A.A.V.V. (2012). Camminando… verso Sant'Agnese e Ospedaletto [Walking… towards Sant'Agnese and Ospedaletto] (in Italian). Gemona: Comunità Montana del Gemonese Canal del Ferro e Valcanale.

Bibliography

- Lorenzi, Arrigo (1897). "a. VIII". Il lago di Ospedaletto nel Friuli [The Lake of Ospedaletto in Friuli] (in Italian). Udine: In Alto – Società Alpina Friulana.

- Marinelli, Olinto (1912). Guida delle Prealpi Giulie [Guide to the Giulian Prealps] (in Italian). Udine: Società Alpina Friulana.

- Clonfero, Guido (1976). Ospedaletto Vive, numero unico [Ospedaletto Lives, special issue] (in Italian). Ospedaletto: Associazione Pro Loco – Ospedaletto.

- Sgobino, Federico; Mainardis, Giuliano; Chiussi, Enrico (1983). Geologia, flora e fauna del Gemonese [Geology, flora, and fauna of the Gemona area] (in Italian). Gemona: Comunità Montana del Gemonese.

- Mainardis, Giuliano; Sgobino, Federico; Tondolo, Maurizio (1992). Parco naturale delle Prealpi Giulie, Comune di Gemona del Friuli [Natural Park of the Giulian Prealps, Municipality of Gemona del Friuli] (in Italian). Gemona del Friuli.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Stoch, Fabio. Atti del convegno "Un Lago nel Parco" [Proceedings of the conference "A Lake in the Park"] (in Italian). Gemona.

- Mainardis, Giuliano; Candolini, Renato (2001). Glemone – Numero Unico 78º Congresso SFF [Glemone – Special Issue 78th SFF Congress] (in Italian). Udine: Società Filologica Friulana.

- Casolo, Ercole Emidio (2011). Le terre emerse dell'Agro Gemonese [The emerged lands of the Gemona countryside] (in Italian). Gemona: Edizioni Associazione Centro Studi Accademia.

- A.A.V.V. (2012). Camminando… verso Sant'Agnese e Ospedaletto [Walking… towards Sant'Agnese and Ospedaletto] (in Italian). Gemona: Comunità Montana del Gemonese Canal del Ferro e Valcanale.

- Simeoni, Pietro (2014). Ospedaletto dai rivoli Bianchi alla Liberazione [Ospedaletto from the Rivoli Bianchi to Liberation] (in Italian). Gemona.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)

External links

- "Zona conservazione Speciale Lago Minisini e Rivoli Bianchi" [Special Conservation Zone Lago Minisini and Rivoli Bianchi] (in Italian).

- "La scheda su Geositi regione F.V.G." [Datasheet on FVG region geosites] (PDF) (in Italian).

- "Forte di Monte Ercole" (PDF) (in Italian). Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016.

- "Mulino Cocconi" [Cocconi Mill] (in Italian). Archived from the original on 24 March 2020.