Kuivajärvi, Suomussalmi

Kuivajärvi

Kuivarvi | |

|---|---|

Village | |

.tif.jpg) Orthodox chapel of Kuivajärvi in 1961 | |

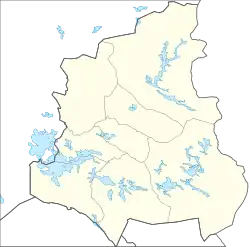

Kuivajärvi Location in Finland  Kuivajärvi Kuivajärvi (Finland) | |

| Coordinates: 64°38′35″N 30°03′36″E / 64.643°N 30.060°E | |

| Country | |

| Region | Kainuu |

| Sub-region | Kehys-Kainuu |

| Municipality | Suomussalmi |

| Time zone | UTC+2 (EET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+3 (EEST) |

Kuivajärvi (Karelian: Kuivajärvi or Kuivarvi)[1] is a village in southeastern Suomussalmi, Finland, near the border with Russia. It is one of three villages in the Kainuu region with a traditionally Karelian-speaking, Orthodox Christian population, along with Hietajärvi and Rimpi.

Kuivajärvi was settled in the late 18th century. Along with Hietajärvi and Rimpi, Kuivajärvi had closer ties to villages in Russian Karelia than to those in Finland until the 1920s, when the border was closed. The village was destroyed during the Winter War, but rebuilt afterwards.

Geography

Kuivajärvi is centered around the eponymous lake Kuivajärvi, with most houses being located near the Saavisenniemi cape of the lake. As of 2002, six houses in the village were inhabited.[2] The village forms a nationally significant cultural heritage site along with neighboring Hietajärvi as well as Rimpi in Kuhmo, all traditionally inhabited by Karelians.[3]

The drainage divide between the Baltic and White Sea basins is located south of Kuivajärvi at the border with Russia. Kuivajärvi and Hietajärvi are located over 200 meters (660 ft) above sea level, but height differences within the area are minor; the highest points are the hills Nuolivaara and Iso Hyrynvaara at slightly over 260 m (850 ft).[4] Fields in the villages have been small, as much of the soil is rocky and prone to frost. Agriculture is no longer practiced, but some former fields have been kept as meadows to preserve a traditional landscape.[5]

History

Kuivajärvi was settled sometime in the late 18th century by Lari and Toarie Huovinen, who came from White Karelia and settled in the area as tenants of Jyrki Ahtonen, whose farm was located in Hietajärvi. Toarie was most likely from Ladvozero, while her husband's place of origin is unclear.[6] According to oral tradition, Lari originally came to Finland to avoid being conscripted into the Russian army and married Toarie while working as a farmhand for Ahtonen.[3]

Until the Russian Revolution, the three Karelian villages in Finland were closely connected to ones in Russia, such as Voknavolok and Babya Guba.[6] The villages had little contact with the rest of Finland until the closure of the Finnish–Russian border in the 1920s, beginning the process of assimilation into mainstream Finnish society.[7]

During the Winter War, the population of Kuivajärvi was evacuated to other parts of Finland. The village was destroyed by the Finnish army in February 1940, with effectively no old buildings remaining.[8] This was done to prevent Soviet soldiers from taking shelter in its buildings.[9] When Kuivajärvi was rebuilt after the war, the returning villagers were not allowed to build their houses in the Karelian style, having to follow a standard plan instead.[8]

A road connecting Kuivajärvi to Saarivaara was finished in 1933 and extended to Hietajärvi in 1956.[5]

Culture

Religion

There has been an Orthodox chapel (eukterion) in Kuivajärvi since the late 19th century.[10] The original chapel burned down in June 1908. A new chapel, built in the Border Karelian style, was finished in 1937, but was destroyed in 1940 with the rest of the village. The third and current chapel was consecrated on 29 June 1958 (the day of Peter and Paul) and was modeled after the previous building, with the addition of an iconostasis.[11]

While many religious traditions such as fasting are no longer commonly observed, Orthodox Christianity remains an important part of the local identity.[7] A local two-day religious festival (praasniekka) was originally held in May to commemorate the translation of the Relics of Saint Nicholas from Myra to Bari (known in Karelian as Kevät-Miikkula), but has been held in July instead since the 1970s. After the fall of the Soviet Union, some old traditions have been reintroduced from villages on the Russian side of the border, where many villagers had relatives.[12]

Languages and dialects

The dialect of the Karelian language traditionally spoken in Kuivajärvi is a Viena Karelian dialect. Nowadays most people speak Finnish, specifically the Kainuu dialect.[13] In 1961, linguist Pertti Virtaranta noted that only a few old people in Kuivajärvi and Hietajärvi still spoke Karelian.[14] Some Karelian influence is still present in the local Finnish speech.[7]

Services

The Kuivajärvi school was established by the Most Holy Synod in 1894, being the first school in Suomussalmi. It was owned by the Orthodox parish of Vaasa until 1928, when it was integrated into the municipal school system. The school was an important cultural center until its closure in 1989.[10] In 1990, the building was turned into a campground by the Orthodox parish of Kajaani, who operated it until 2009. The building burned down in February 2012.[15]

Domnan pirtti is a venue for local events that was established as a village hall in 1964.[16] In the 1980s, there were plans to establish a folk high school to teach the Karelian language at Domnan pirtti. The school was never established, with the venue instead mostly being used as a travel center and a meeting place for locals.[17]

References

Citations

- ^ Karlova, Olga (5 February 2024). "Vienankarjalaini pakinaklupi kevyällä 2024, toini pakinakerta". blogs.uef.fi (in Karelian). University of Eastern Finland. Retrieved 14 August 2025.

- ^ Tauriainen 2004, p. 11–13.

- ^ a b "Kainuun vienalaiskylät" [Viena Karelian villages in Kainuu]. Valtakunnallisesti merkittävät rakennetut kulttuuriympäristöt RKY (in Finnish). Finnish Heritage Agency. Retrieved 14 August 2025.

- ^ Tauriainen 2004, p. 18.

- ^ a b Tauriainen 2004, pp. 25–32.

- ^ a b Panteleimon et al. 2021, pp. 10–13.

- ^ a b c Panteleimon et al. 2021, pp. 32–33.

- ^ a b Tauriainen 2004, p. 29.

- ^ Panteleimon et al. 2021, p. 50–51.

- ^ a b Tauriainen 2004, p. 33.

- ^ Panteleimon et al. 2021, pp. 41–45.

- ^ Panteleimon et al. 2021, p. 15.

- ^ Torikka, Marja (2004). "Karjala – kieli, murre ja paikka". kotus.fi (in Finnish). Institute for the Languages of Finland (Kotus). Archived from the original on 23 March 2023. Retrieved 14 August 2025.

- ^ Joki, Leena (31 October 2017). "Karjalan kielen sanakirja kansissa ja verkossa". kotus.fi (in Finnish). Institute for the Languages of Finland (Kotus). Retrieved 14 August 2025.

- ^ Marjomaa, Reijo (2012). "Onttoni Miihkalin leirikeskus tuhoutui tulipalossa" (PDF). Paimen-Sanomat (in Finnish). Metropolitanate of Oulu. p. 9. Retrieved 14 August 2025.

- ^ Tauriainen 2004, pp. 38–43.

- ^ Lemmetyinen, Anne-Mari K. (3 June 2015). Karjalan kielen taival ei-alueelliseksi vähemmistökieleksi Suomessa [The journey of the Karelian language to a non-regional minority language in Finland] (Thesis) (in Finnish). University of Eastern Finland. p. 43. urn:nbn:fi:uef-20150497. Retrieved 14 August 2025.

Cited sources

- Panteleimon (metropolitan); Heikkilä-Palo, Liisa; Rantala, Marja (2021). Kainuun vienalaiskylät (in Finnish). Uusi-Valamo: Valamo Kustannus. ISBN 978-952-5495-73-7.

- Tauriainen, Suvi (2004). Vienan veräjillä : Suomussalmen vienalaiskylien maisema-alueen hoito- ja käyttösuunnitelma (digital version) (in Finnish). Kajaani: Kainuun ympäristökeskus. ISBN 952-11-1668-4. Retrieved 14 August 2025.