Kingdom of Marudu

Rajahnate of Marudu Kingdom of Marudu كراجأن مارودو Kerajaan Marudu | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1771–1845 | |||||||||||||||

Flag | |||||||||||||||

| Status | Protectorate of Sulu and Brunei (1771–1830) Recognized Independent (1830–1845)[1] | ||||||||||||||

| Capital | Marudu Bay (until 1830) Kota Marudu | ||||||||||||||

| Common languages | Malay and Tausug | ||||||||||||||

| Religion | Sunni Islam | ||||||||||||||

| Demonym(s) | Maruduan | ||||||||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||||||||

| Raja | |||||||||||||||

• until 1845 | Syarif Osman (last Raja of Marudu) | ||||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||||

• Kingdom established | 1771 | ||||||||||||||

| 1845 | |||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

| Today part of | Malaysia | ||||||||||||||

The Rajahnate of Marudu, or Kingdom of Marudu (Malay: كراجأن مارودو, romanized: Kerajaan Marudu), was a dominant kingdom amongst of many petty kingdoms in Eastern Sabah, it was centered around Marudu Bay, Sabah.[2] The kingdom was founded in 1771.

History

The Kingdom of Marudu traces its origins in the Twenty Years' War, where it was used as a base of operations for Sulu privateers, pirates and soldiers.[3]

Before the appointment of Syarif Osman, Marudu were back and forth occupied by both Brunei and Sulu until 1830.[2] When Omar Ali Saifuddin II to the Jamalul Kiram I.

After becoming the governor of Marudu, Osman transformed Marudu into a Kingdom,[1] leaving his protectorate status from the Sulu Sultanate. He had strong influence on Eastern Sabah, making alliances amongst other Sabahan princes.[1] British attempts to drive the Sultan of Sulu's followers out of the region failed. And a punitive expedition by the "White Rajah" James Brooke in 1845 with the defaming reason of Marudu being a base of operations for pirates.[1]

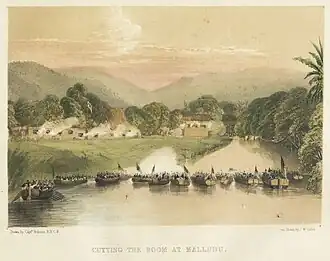

After firing a cannon shot at the British at Kota Marudu, battle ensued, Talbot's men were exposed to cannon fire for about an hour. Of the six to eight British dead and about twenty wounded, most fell during this initial exchange of fire. It is unclear whether Osman's men fired at any significant volume afterward. Stephen Evans attributed the relatively rapid end of the battle to an operator's error by the fortress gunners[4]

Abbas/Bali explained Osman's defeat as treason and underestimation of the naval gunfire, as Osman had not expected the guns to reach his fortress. The interpretation that Osman lost the battle due to the enemy's superior force may be the most accurate. Shortly after the initial exchange of fire, Talbot landed some of his men on the right bank and aimed rockets at the fortress. The rocket party landed on the right bank and fired with good effect into the stockade.[1]

Syarif Osman likely didn't expect the British to have weapons with such a range at their disposal. The rockets caused devastating damage to the fortress. Nevertheless, the defenders tried to use the still-functioning cannons to prevent the British from penetrating the fortifications. The persistent bombardment and defense of the barrier may have been Osman's only real chance to prevent the storming of his fortress and city. What Rutter described as the devil-may-care spirit of Osman's men was more likely an expression of a desperate defense. When the British finally broke through the barrier, some hand-to-hand combat still took place, but most of the defenders probably had no doubt that the battle was finally decided. They fled, even though they might have had the best chance against the numerically inferior British in close combat. Perhaps the loss of capable fighters due to the rocket fire was too great for an effective defense.[1]

Economy

During the Twenty Years' War, the economy of Marudu was primarily pirate raids along the Bruneian coast. Similar to the Sulu Sultanate.[3] During the reign of Syarif Osman, they traded with their neighbors such as the Sulu and to Singapore.[1]

Culture

Their culture would have been similar to the Sulu Sultanate until 1830. However Syarif Osman championed mixing Kadazan-Dusun, Sama-Bajau and Malay cultural titles. As he used the Malay title "Rajah" as well.[1]

See also

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h Gerlich, Bianca. "Syarif Osman". Mompracem.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ a b Dalrymple 1793.

- ^ a b Abdul Rashid 2020.

- ^ Pascoe et al.