Aboriginal breastplate

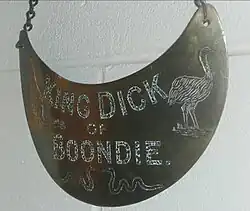

Aboriginal breastplates (also called king plates or Aboriginal gorgets) were a form of regalia used in pre-Federation Australia by white colonial authorities to recognise those they perceived to be local Aboriginal leaders. The breastplates were usually metallic crescent-shaped plaques worn around the neck by wearer.[1]

These plates were modified gorgets and they were initially modified copies of those worn by infantry officers in Australia until 1832.[2] They soon became larger and were soon at least twice the size of those given to the military.[3]

Aboriginal people did not traditionally have kings or chiefs. They lived in small clan groups with several eldersg—certain older men and women—who consulted with each other on decisions for the group. By appointing kings of tribes, and granting them king plates, colonial authorities went against the more collegiate grain of traditional Aboriginal culture.[1]

Brief history

In the 19th century, king plates were given by numerous communities in various Australian States to esteemed Aboriginal men and women, who were usually elders of their particular tribal or kinship group. The plates were presented to perceived 'chiefs', courageous men and to 'faithful servants'. There have been suggestions that the presentation of breastplates also had a great deal to do with whether or not the recipient was seen as useful or respected by the white Australian community of the area in question.[1] The oldest known breastplate was given in 1815 although it is recorded that James Cook gave bronze medals, an early form, to Aboriginal people he met at Adventure Bay.[3]

The plates were typically made from industrial metals such as brass or iron. A typical format of inscribing the breastplates was to write the recipients name across the upper part of the plate's face, with the title below, sometimes 'King', 'Queen', or 'Chief'. Some particularly distinguished Aboriginal characters are said to have ironically had the royal seal of Queen Victoria engraved somewhere on the plate to add an extra air of prestige. While some Aboriginal people wore their breastplates with pride, others saw them as yet another insult to their culture from the white European settlers.[4]

The practice of presenting respected Aboriginal leaders with breastplates declined in the post-Federation years,[5] becoming virtually unheard of by the end of the 1930s.

Aboriginal breastplate holders

Little is known about individual Aboriginal people who were awarded breastplates. Some are merely inscribed "King", "Queen", or "Prince", while others are inscribed for some type of service of merit for which they were awarded. There is differing reference to how breastplates were received by Aboriginal people, some wore them proudly, while others destroyed them.[1]

Aboriginal breastplates can be difficult to document and this work is made the more difficult as it is now many decades since they were last worn. Most pre-date living memory, with the majority having been given out between the mid nineteenth and very early twentieth century. Further complicating matters is the change in place names, particularly property names. Many pastoral stations and farms have either been subsumed into larger properties or divided into smaller ones at various times. With this came name changes, with some names disappearing altogether. The bearers of breastplate are important historical figures, however many remain unknown to present and future generations.[1]

Notable recipients

Recipients include;

- Bilin Bilin (c1820-1901) who was presented with one and given the title 'Jackey Jackey - King of the Logan and Pimpama'.[6]

- Bungaree (c1771-1830) who received one in 1815 from Governor Lachlan Macquarie who named him the "Chief of the Broken Bay Tribe".[7][8]

- Kerwalli (c1832-1900) was given the breastplate and the title 'King Sandy' in 1913.[9][10]

- Yanggendyinanyuk (c1834-1886) who received one following his rescue of a child in 1883.[11]

References

- ^ a b c d e "Aboriginal breastplates". National Museum of Australia. Retrieved 14 August 2025.

- ^ Troy, Jakelyn (1993). "National Museum of Australia - Introduction". National Museum of Australia. Retrieved 14 August 2025.

- ^ a b National Museum of Australia. "Establishment of a tradition in Australia". National Museum of Australia. Retrieved 14 August 2025.

- ^ "Aboriginal people's reactions". National Museum of Australia. Archived from the original on 2 May 2016. Retrieved 24 August 2016.

- ^ National Museum of Australia, List of breastplates, Australian Government, archived from the original on 14 June 2015

- ^ Best, Ysola (1993). "Bilin Bilin : king or eagle". AIATSIS. Retrieved 14 August 2025.

- ^ McCarthy, F. D., "Bungaree (c. 1775–1830)", Australian Dictionary of Biography, Canberra: National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, retrieved 14 August 2025

- ^ "Sydney, Sitting Magistrate—W. Broughton, Esq". Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser. 4 February 1815. p. 1. Retrieved 21 January 2020.

- ^ Kerkhove, Ray. "Kerwalli (c. 1832–1900)". People Australia. Retrieved 14 August 2025.

- ^ "King Sandy". Molong Argus. Vol. 25, no. 913. New South Wales, Australia. 28 March 1913. p. 1. Retrieved 14 August 2025 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ Giese, Jill, "Yanggendyinanyuk (c. 1834–1886)", Australian Dictionary of Biography, Canberra: National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, retrieved 29 July 2025

External links

![]() Media related to King plate at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to King plate at Wikimedia Commons

- Troy, Jakelin (1993), Aboriginal breastplates, National Museum of Australia